“I Can Either Be World Champion or Die"

‘The Death Years’ and improved safety in F1

A selection of Ferrari F1 cars pictured in 2005 (Source: Edwin van Ness via Flickr)

A selection of Ferrari F1 cars pictured in 2005 (Source: Edwin van Ness via Flickr)

“Racing is a drug. I’m addicted to it.”

Harry Schell’s quote embodies many in motorsport, and the adrenaline provided by racing. It is an addiction difficult to give up.

For Schell and countless others that addiction was costly. Deaths were common and often horrific in F1’s early years.

It is safer now, partially because of lessons learnt from the deaths of some of F1’s best and brightest.

'The Death Years'

Three-time world champion Jackie Stewart survived the 'Death Years' and is still alive today (Source: Rob Mieremet via WikimediaCommons)

Three-time world champion Jackie Stewart survived the 'Death Years' and is still alive today (Source: Rob Mieremet via WikimediaCommons)

Between 1950 and 1979, 41 people died in F1 or F1-related events.

These figures don’t include the deaths of anyone who died in F2 or unofficial testing.

Three-time world champion Jackie Stewart believes he attended the funerals of 57 drivers.

Stewart walked away from the sport one race earlier than planned in 1973 when teammate Francois Cevert was killed.

Peter Collins

6/11/1931-3/8/1958

Collins was an early British star of F1 alongside Mike Hawthorn and Stirling Moss.

His and Hawthorn’s rivalry with their Ferrari teammate Luigi Musso was one of the fiercest in F1 history, fuelled by on and off-track animosity.

Just a month before Collins died, Musso was killed at the 1958 French Grand Prix, suffering fatal head injuries after driving into a ditch.

Following Musso's death, Collins surged into title contention with victory at the British Grand Prix.

Collins won the 1956 French Grand Prix (Source: British Pathe)

In the following German Grand Prix, Collins span into a ditch. Flung out of the car, he hit a tree and died of severe head injuries later that day.

Disillusioned after Collins’ death, Hawthorn retired in 1958 despite becoming world champion. He died in a car crash in January 1959.

Collins with mechanic Ascanio Lucchi, Ferrari head Enzo Ferrari and test driver Martino Severi ahead of the 1957 Mille Miglia (Source: Louis Klemantaski via Wikimedia Commons)

Collins with mechanic Ascanio Lucchi, Ferrari head Enzo Ferrari and test driver Martino Severi ahead of the 1957 Mille Miglia (Source: Louis Klemantaski via Wikimedia Commons)

Collins (left) with Juan Manuel Fangio (second from left) and Mike Hawthorn (centre) following the 1957 German Grand Prix (Source: Willy Pragher via WikimediaCommons)

Collins (left) with Juan Manuel Fangio (second from left) and Mike Hawthorn (centre) following the 1957 German Grand Prix (Source: Willy Pragher via WikimediaCommons)

Wolfgang von Trips

4/5/1928-10/9/1961

Few crashes are as tragic as the one that killed von Trips in 1961.

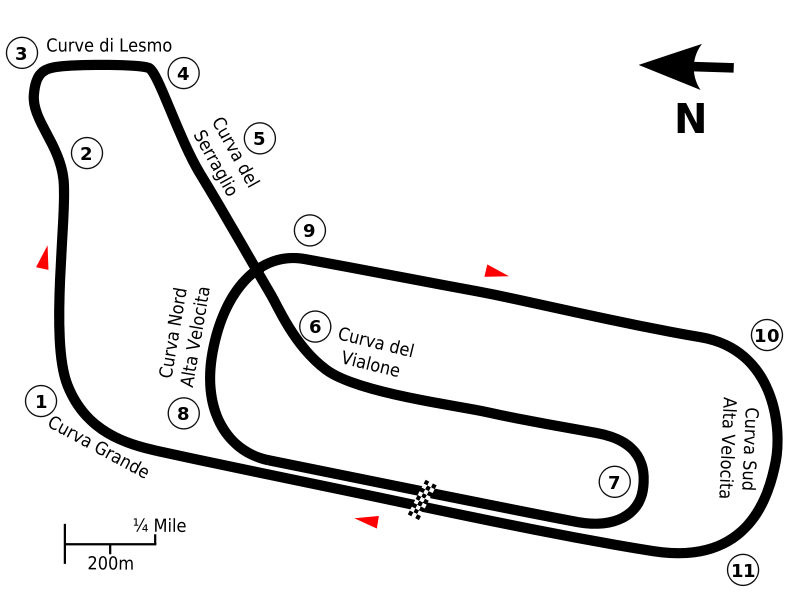

Injured at the Italian Grand Prix in 1956 and 1958, he headed to Monza in 1961 leading the world championship.

Remembering Wolfgang von Trips, born #OnThisDay in ’28. Had he not been killed at Monza in ’61, he might have become world champion. Pic: en route to 2nd at Nürburgring that year in the pretty & rapid Ferrari 156 ‘sharknose’. Great photo by Bernard Cahier, Paul-Henri’s dad. (1/2) pic.twitter.com/MXR6eX5wi3

— Matt Bishop (@TheBishF1) May 4, 2020

Just two laps in his car collided with that of Jim Clark’s and went up a 1.5m embankment, where spectators stood behind chain fencing.

He was flung out his car and died instantly, with 11 spectators killed when his Ferrari broke through the fencing. Four more later died of their injuries.

Despite multiple deaths, the race continued, with von Trip’s teammate Phil Hill winning the race and the world title.

Von Trips (centre) pictured in 1958 (Source: Joop van Bilsen via WikimediaCommons)

Von Trips (centre) pictured in 1958 (Source: Joop van Bilsen via WikimediaCommons)

A statue of von Trips in Kerpen-Horrem (Source: Tohma via WikimediaCommons)

A statue of von Trips in Kerpen-Horrem (Source: Tohma via WikimediaCommons)

Jochen Rindt

18/4/1942-5/9/1970

“At Lotus, I can either be world champion or die,” said Rindt.

Rindt joined Lotus ahead of the 1969 season, after they had won the Constructors and Drivers Championships in 1968.

Notoriously unreliable, Lotus were involved in 31 crashes from 1967-69, but in the revolutionary Lotus 72 Rindt won five of the first nine races in 1970.

Jochen Rindt’s letter to Colin Chapman regarding the safety of Lotus’s cars. He also commented, “At Lotus, I can either become champion or die.”

— Nathan (@b1gnate_11) March 27, 2021

In 1970, he was killed at age 28 after a brake failure while leading the standings. He still won the title. pic.twitter.com/EbZqOKbKG5

Ahead of race ten in Monza, Rindt's breaks failed during practice. Crashing into a loose barrier, he suffered fatal throat injuries after slipping inside the car and hitting his belt buckle.

It later emerged that Rindt’s belts were loose and he was not wearing a crotch strap.

The Austrian's championship lead was so commanding that, despite four more races, he won the world title by five points.

Rindt at the 1970 Dutch Grand Prix (Source: Joost Evers via WikimediaCommons)

Rindt at the 1970 Dutch Grand Prix (Source: Joost Evers via WikimediaCommons)

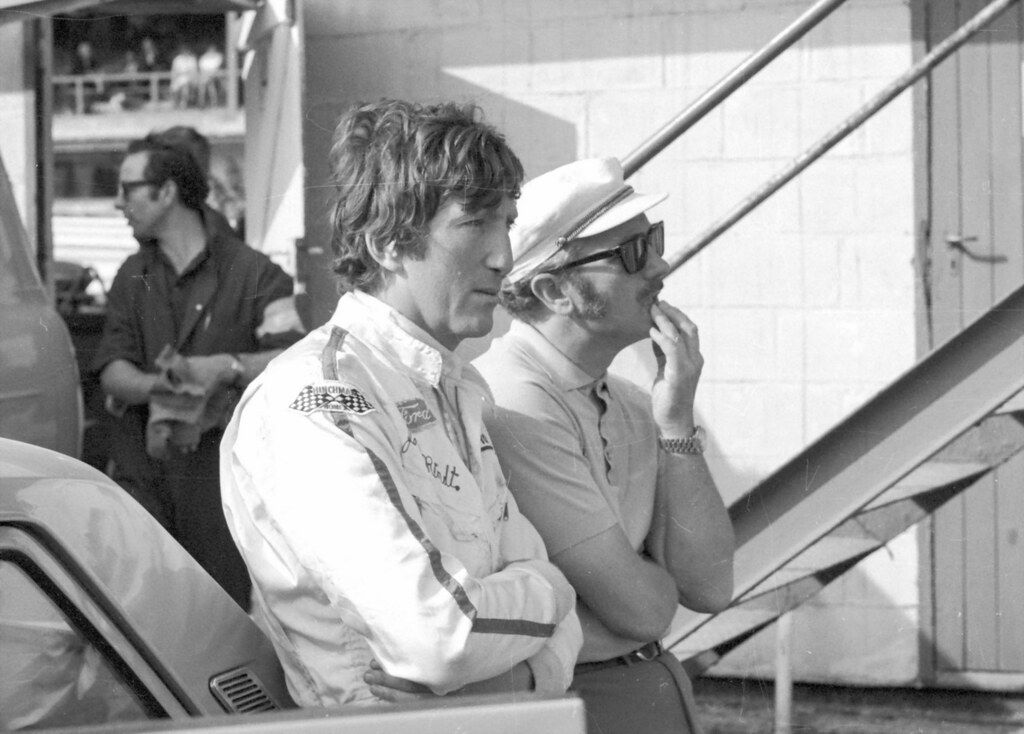

Rindt with Lotus team manager Colin Chapman (Source: Jim Culp via Flickr)

Rindt with Lotus team manager Colin Chapman (Source: Jim Culp via Flickr)

Roger Williamson

2/2/1948-29/7/1973

Few moments in F1 history are as infamous as Williamson’s death at the 1973 Dutch Grand Prix.

On lap eight, his car flipped over and immediately burst into flames.

Williamson was trapped inside the car, and poorly trained and poorly-equipped marshals were unable to help.

There was no significant attempt to rescue Williamson until fellow driver David Purley pulled over to assist.

Footage of Purley attempting to extinguish the flames and beckon other drivers to help remains horrifying to this day.

As the race continued, no other drivers stopped as they believed Purley had escaped from the car.

A fire engine eventually arrived from across the circuit. By then, Williamson had died of asphyxiation in just his second F1 race.

David Purley was interviewed following the crash (Source: AP Archive)

Williamsons burnt-out car following his fatal crash (Source: R. Mieremet via WikimediaCommons)

Williamsons burnt-out car following his fatal crash (Source: R. Mieremet via WikimediaCommons)

A statue of Williamson was erected at Donnington Park on the 30th anniversary of his death (Source: Ben Sutherland via Flickr)

A statue of Williamson was erected at Donnington Park on the 30th anniversary of his death (Source: Ben Sutherland via Flickr)

Ronnie Peterson

14/2/1944-11/9/1978

Runner-up in 1971, the ‘SuperSwede’ was second in the 1978 title race, trailing Lotus teammate Mario Andretti heading into Monza.

In a multiple-car opening lap crash, Peterson’s car hit a barrier and caught fire before ricocheting back onto the track.

Suffering minor burns, he was pulled out by James Hunt, though his legs were badly broken.

Peterson winning the Moncao Grand Prix in 1974 (Source: AP Archive)

Vittorio Brambilla was also seriously injured but it took 20 minutes for either to receive treatment.

Delays in treating Peterson on track and in hospital meant he developed a fat embolism, which led to kidney failure. He died the next morning.

He still finished second behind Andretti in the title race.

Peterson at the British Grand Prix in 1976 (Source: Gillfoto via WikimediaCommons)

Peterson at the British Grand Prix in 1976 (Source: Gillfoto via WikimediaCommons)

(Source: Gillfoto via WikimediaCommons)

(Source: Gillfoto via WikimediaCommons)

A statue of Peterson in Orebro, Sweden, unveiled in 2003 (Source: Hakan Henriksson via WikimediaCommons)

A statue of Peterson in Orebro, Sweden, unveiled in 2003 (Source: Hakan Henriksson via WikimediaCommons)

Alberto Ascari died in a crash while testing (Source: Alan Farrow via Flickr)

Alberto Ascari died in a crash while testing (Source: Alan Farrow via Flickr)

Jim Clark died in a F2 race in Germany in 1968 (Source: Racing in America via Flickr)

Jim Clark died in a F2 race in Germany in 1968 (Source: Racing in America via Flickr)

The End of the 'Death Years': Better Care and Safer Drivers

Sid Watkins attends to Ralf Schumacher after an accident at the 2004 US Grand Prix (Source: Kuyper Hoffman via WikimediaCommons)

Sid Watkins attends to Ralf Schumacher after an accident at the 2004 US Grand Prix (Source: Kuyper Hoffman via WikimediaCommons)

Watkins, who died in 2012, with a tribute plate he received from drivers in 1985 (Source: Ben Sutherland via WikimediaCommons)

Watkins, who died in 2012, with a tribute plate he received from drivers in 1985 (Source: Ben Sutherland via WikimediaCommons)

Peterson’s death was a turning point.

On Bernie Ecclestone's request, Sid Watkins was hired as F1 race doctor earlier that season.

Prevented from treating Peterson quickly, Watkins demanded immediate improvements to medical facilities.

Safety equipment, an anaesthetist, and medical vehicles were all present at the next race in America.

People have died racing since then, though the drop in numbers is remarkable.

That is partially down to a greater number of medics placed around circuits, and able to respond to incidents quickly.

When Mika Hakkinen was critically injured in practice at the 1995 Austrian Grand Prix, doctors were with him in 15 seconds.

Watkins arrived afterwards and helped save Hakkinen’s life. Hakkinen would have likely died 20 years before, but recovered and later became a two-time world champion.

Years after his passing, Sid Watkins is still saving lives in Formula 1.#F1 pic.twitter.com/V0ojpAvKmD

— Jeff Kirk (@JeffreyNKirk) November 29, 2020

Other improvements include circuit modifications, with longer, dangerous tracks shortened or replaced to increase medical access and safety.

Introduced in the 1960s, Armco Barriers helped minimise crashes. These ensured cars experienced less serious damage, and mean less risk to drivers and spectators.

In 1972, six-point harness seatbelts were made compulsory, guaranteeing drivers stay inside cars and cannot be ejected as Collins and von Trips were.

Drivers can no longer slip like Rindt, as they are strapped in with the same level of protection as fighter pilots, whilst fire-retardant uniforms for drivers, medics and marshals ensure fires can be dealt with and are more survivable.

Safety tests on cars are also more rigorous than ever.

“We have a huge number of safety tests to do now,” says an F1 engineer, who wishes to remain anonymous for contractual reasons.

“The nose impact test is a pretty hard one. The FIA have increased the load and energy the car has to absorb, which essentially protects drivers from impact against a barrier but also makes sure you can have an oblique impact without the nose snapping off.

“We have the side impact tests, which we developed with tubes that protect the driver. The tubes don't absorb much energy but do make the chassis stronger and less likely to be damaged.

“Also, the side of the chassis has got a thick plate made of zylon attached to it, almost armoured plating, which prevents serious accidents. From next year that’s going under the floor of the car as well.”

Monza, pictured as the 1922 circuit, has now been shortened with racing on just the outside lap (Source: WikimediaCommons)

Monza, pictured as the 1922 circuit, has now been shortened with racing on just the outside lap (Source: WikimediaCommons)

Modern F1 cars go under extreme testing before being allowed to race (Source: Artes Max via WikimediaCommons)

Modern F1 cars go under extreme testing before being allowed to race (Source: Artes Max via WikimediaCommons)

Halo: A Life-Saving Innovation

Introduced in 2018, the Halo is a shield over driver’s heads and chests.

Calls for such protection grew when Jules Bianchi hit a crane head-first at the 2014 Japanese Grand Prix, and died following a nine-month coma.

“The FIA had to react to such accidents,” says the F1 engineer.

“FIA engineer Andy Miller worked on the Halo with Mercedes and created a design.

“They did some testing, firing wheels at a dummy cockpit with the Halo on to ensure it would survive significant impact. Then they devised load cases and formalised what we had to do.

“It can be brought from two or three different companies, all of whom had to pass various tests, and we have to prove that the chassis' attachment points are strong enough to retain it under impact.”

The Halo was largely unpopular with drivers when introduced. Two crashes have since highlighted its importance.

At the 2018 Belgian Grand Prix, an opening lap crash resulted in Fernando Alonso’s McLaren landing on the Halo of Charles Leclerc’s Sauber.

A 3D simulation of Alonso and Leclerc's crash (Source: Motorsport Indonesia)

Both escaped unharmed, and most believe Leclerc would have died without the Halo.

It also proved vital in saving Romain Grosjean's life at last year's Bahrain Grand Prix.

The sport was left momentarily shaken when his car split into two and burst into flames after piercing a barrier.

The Frenchman survived with fairly minor burns to his hands. The Halo protected him from the barrier and the ensuing fireball.

New regulations will be introduced in 2022 to ensure that no car splits in two like Grosjean’s did.

Max Verstappen behind his Halo in 2018 (Source: Sportniews.nl via WikimediaCommons)

Max Verstappen behind his Halo in 2018 (Source: Sportniews.nl via WikimediaCommons)

Lewis Hamilton in action after the Halo was introduced (Source: Pixabay)

Lewis Hamilton in action after the Halo was introduced (Source: Pixabay)

Former Sauber driver Leclerc now races for Ferrari (Source: Xavi Yuahanda via Wikimedia Commons)

Former Sauber driver Leclerc now races for Ferrari (Source: Xavi Yuahanda via Wikimedia Commons)

Grosjean will race in IndyCar this season (Source: Morio via WikimediaCommons)

Grosjean will race in IndyCar this season (Source: Morio via WikimediaCommons)

Antoine Hubert’s tragic death in an F2 race at Spa in 2019 demonstrates that motorsport will never be fully safe.

However, the efforts of Watkins and the FIA have certainly made the sport much safer.

From 1994 to 2015, no drivers died during an F1 weekend- the longest gap in history.

Hopefully, Bianchi's death remains the last.