20 years since 28

LGBT+ education and visibility in schools, 20 years after the repeal of Section 28

"a pretended family relationship"

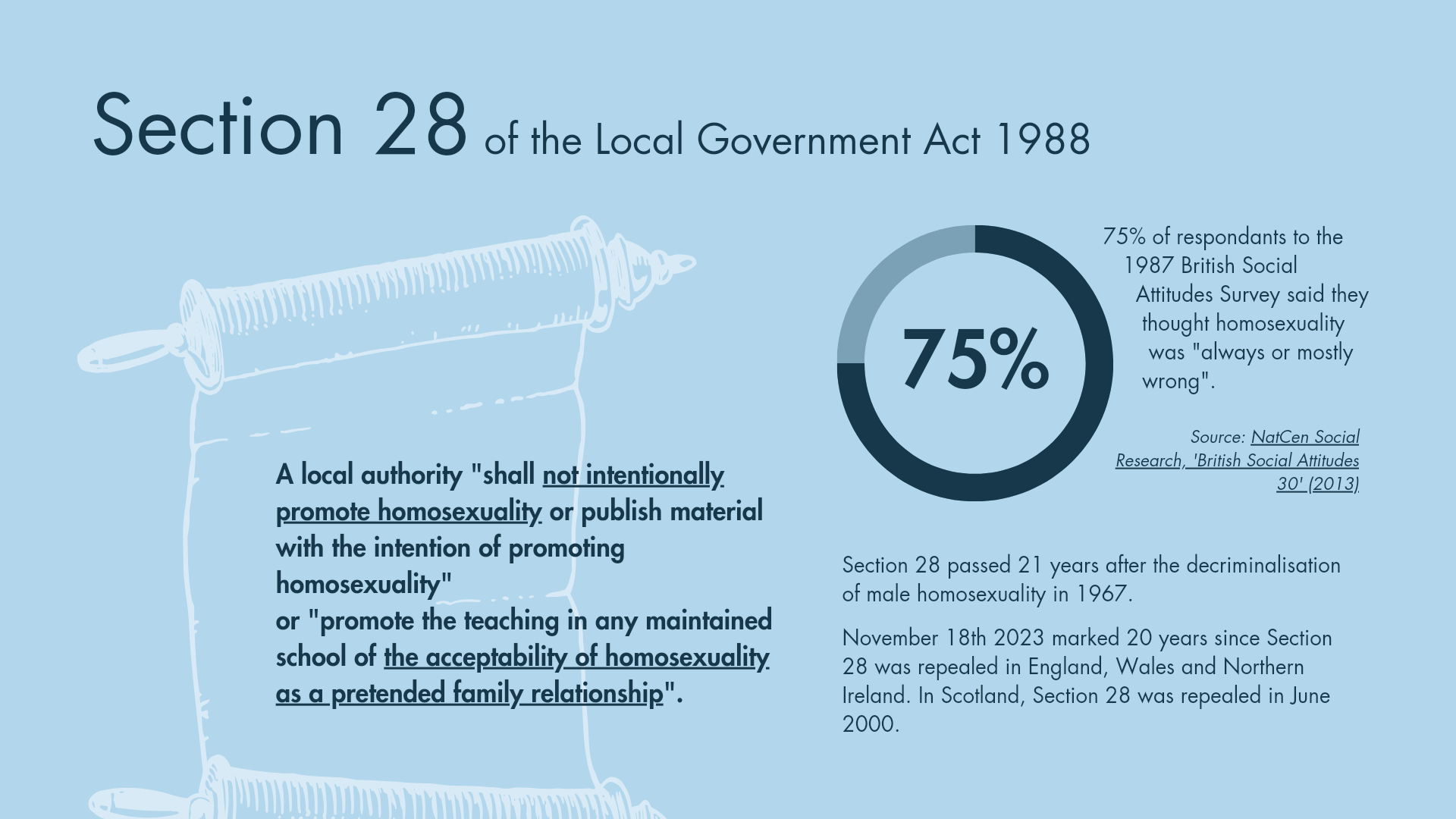

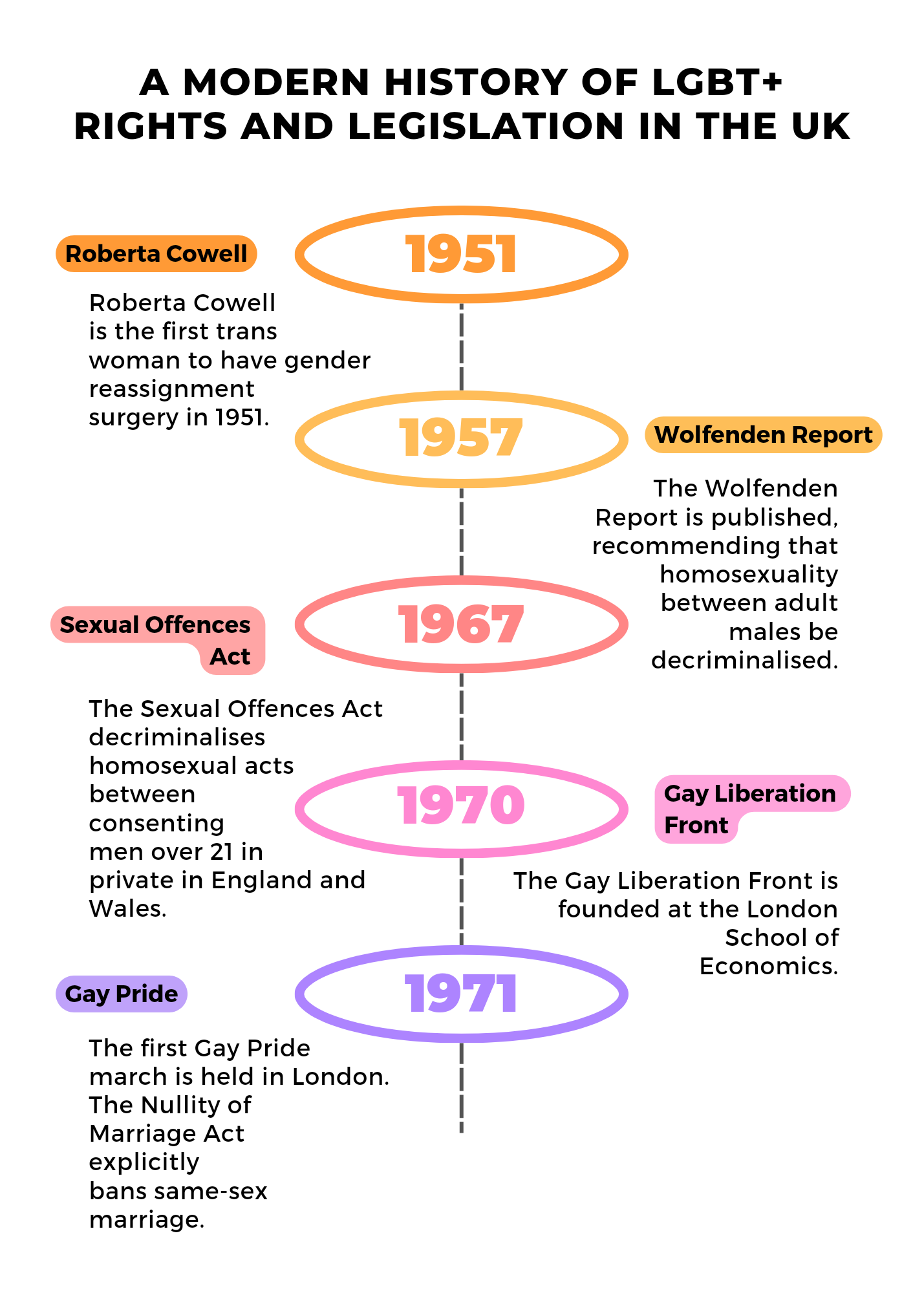

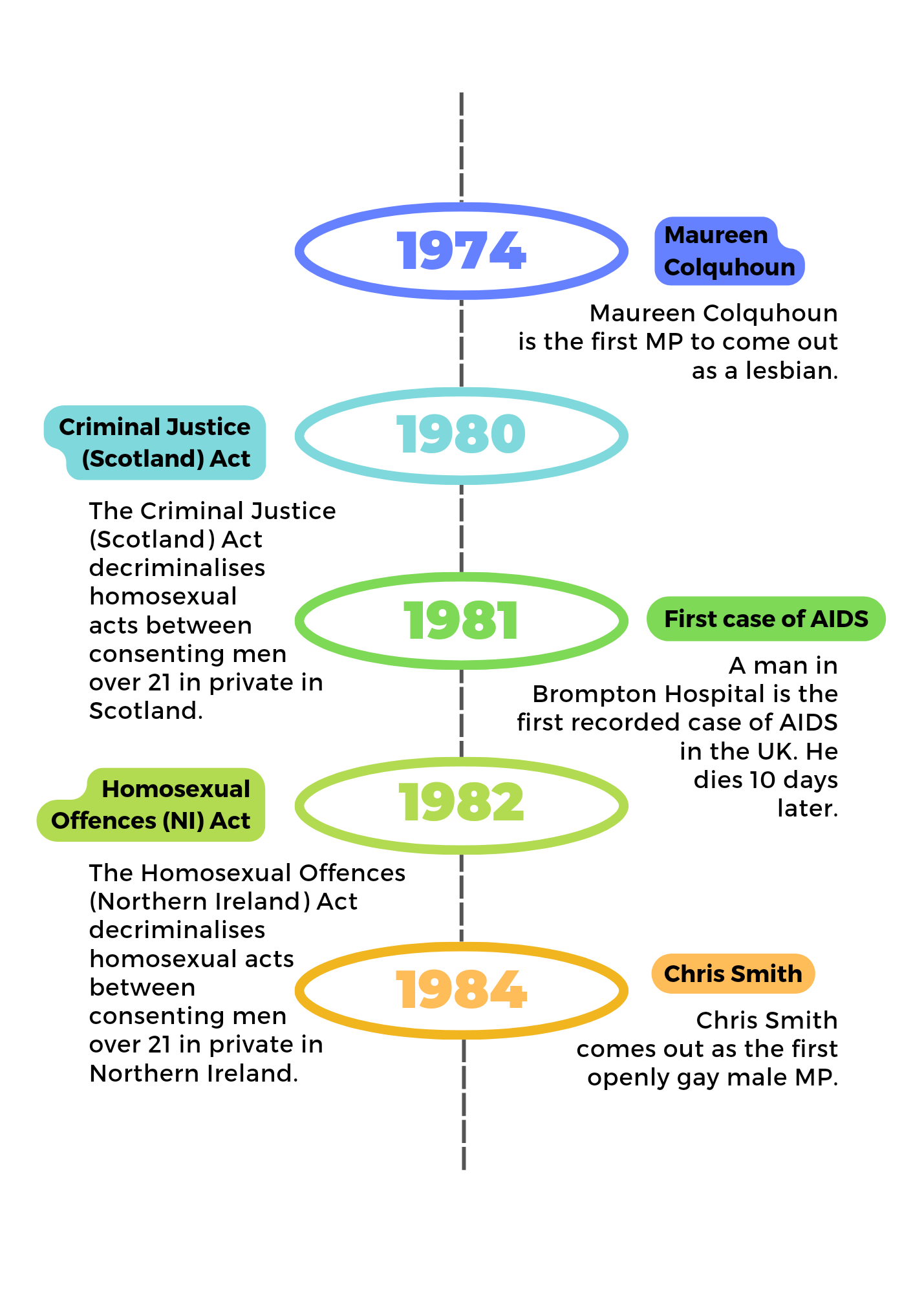

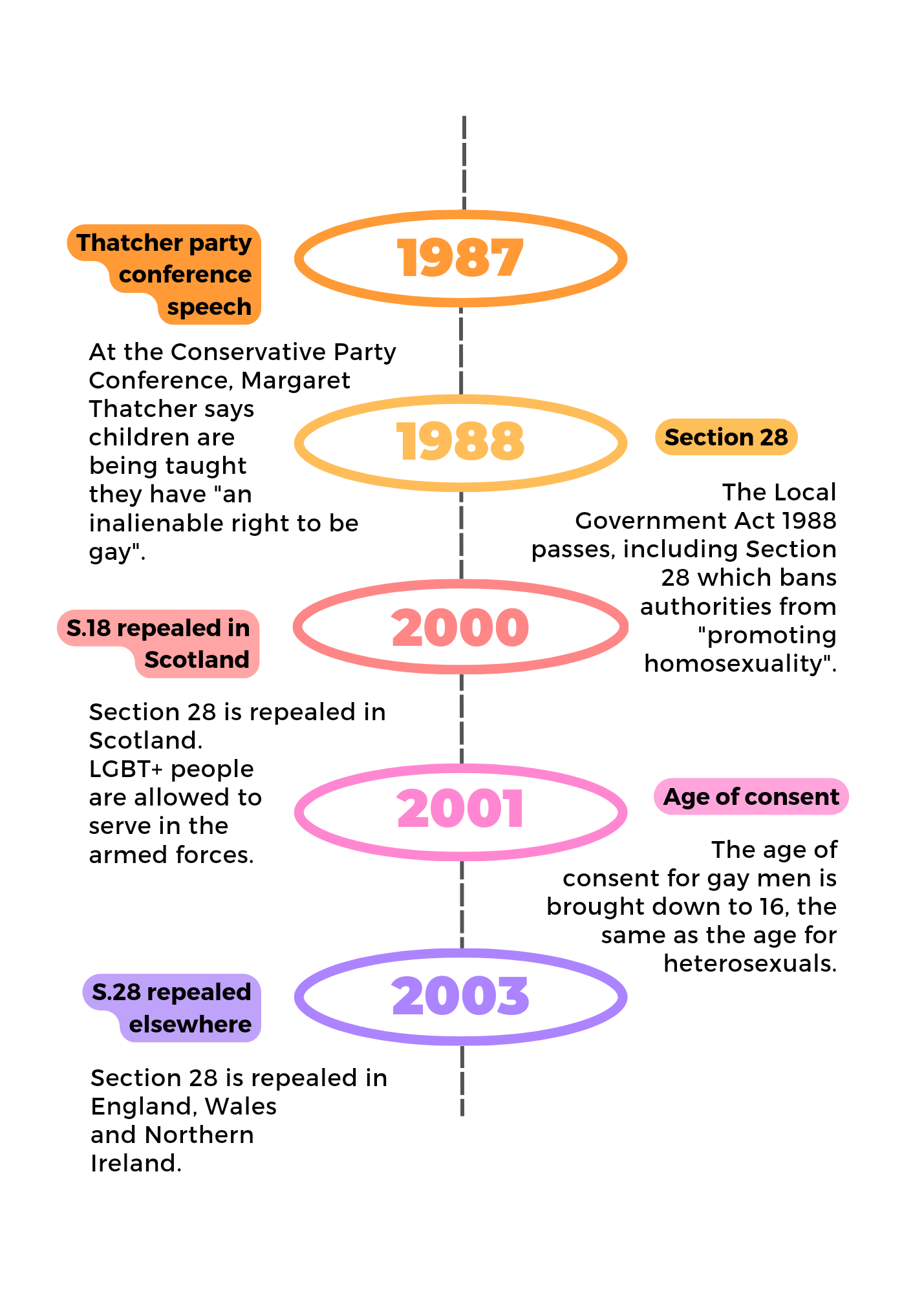

In 1988 the Local Government Act passed, with Section 28 banning local authorities from "promoting homosexuality".

The legislation meant that schools and local government could not address LGBT+ issues, and it lead to an increased erasure of LGBT+ visibility in the 1990s and 2000s.

Section 28 was repealed in Scotland in June 2000, and in England and Wales in November 2003. Since then, charities have worked with young people to increase LGBT+ education and awareness.

In September 2020, inclusive sex and relationships education became compulsory in schools.

In October 1987, five months before the Local Government Act passed, then-prime minister Margaret Thatcher delivered a speech to the Conservative Party Conference. During the speech she claimed the party’s national curriculum would, among other things, address the fact that children were being taught they had “an inalienable right to be gay”.

Credit: LGBT+ marketing on YouTube.

Credit: LGBT+ marketing on YouTube.

History, impact and legacy

In practice, Section 28 meant councils could not directly represent their LGBT+ constituents, and schools could not openly discuss queer histories or experiences.

Dr Isabell Dahms, a lecturer in Queer History at Goldsmiths University said: “Section 28 made it clear that the state would not recognise and support queer individuals and families.

“After the gay liberation movements of the 70s, this was seen as an attempt to push queer issues back into the realm of the private.”

She added: “Section 28 was a civil law, not a criminal law. It regulated what a local authority could do but it couldn’t take any individuals to court. In fact, no case was ever brought to court.

“But Section 28 led to self-censorship by city councils, art venues, and schools. This then had an effect on artists, performers, teachers and students. For example, funding was withdrawn from arts and youth projects and educational and resource materials were censored.”

In schools, any sex and relationships education that was taught could not include education on same-sex relations. In 1986 the government launched its famous ‘AIDS: Don’t Die of Ignorance’ health campaign in response to the crisis, which was a worldwide epidemic by the late 1980s. However, after Section 28 passed in 1988 schools were unable to provide their pupils with information on the topic. Teachers were also disinclined to combat homophobic or transphobic bullying.

The Labour government tried to repeal Section 28 in February 2000, but Baroness Young successfully led a campaign to defeat it – a defeat the then-shadow Education Secretary Theresa May called a “victory for commonsense”.

In Scotland, the Ethical Standards in Public Life Act 2000 repealed Section 28. A repeal eventually passed in England and Wales in November 2003 as part of the new Local Government Act. Kent Council upheld its own version of Section 28 until the Equality Act 2010 overruled it.

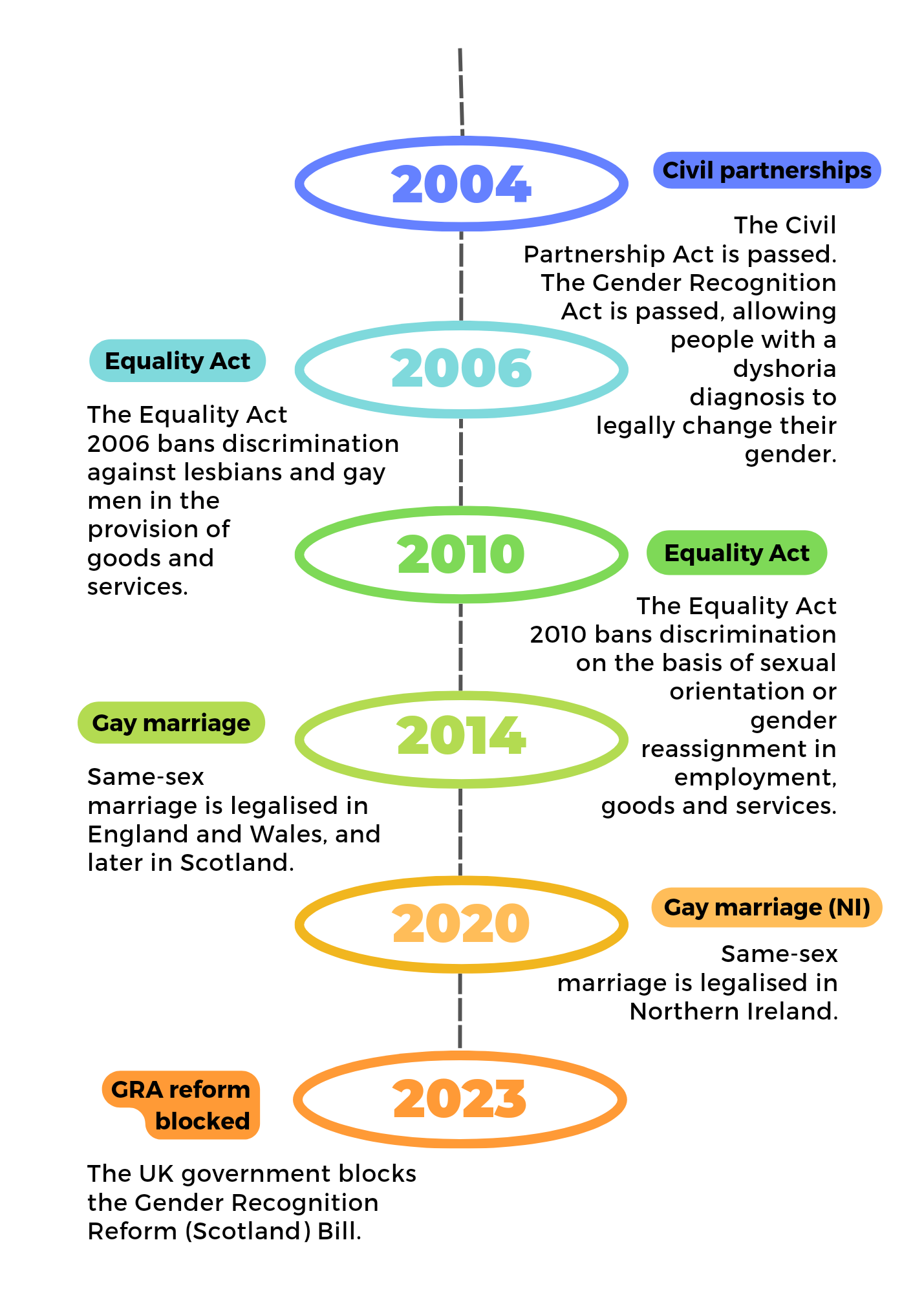

Today, 30 years on from its repeal, the legacy of Section 28 is ongoing. A survey by the charity Just Like Us in 2021 found that 48% of pupils aged 11-18 had received little to no positive messaging about LGBT+ identities in the last 12 months. In 2018, the Government Equalities Office’s national LGBT+ survey found that only 3% of respondents had discussed sexual orientation and gender identity in school, and that 9% of the most serious incidents relating to students being outed, harassed or excluded were perpetrated by teaching staff.

Jack Helles, who left secondary school in 2018, said: “In my school we never had any sort of LGBT+ sex education.

“There were two openly gay guys in my year: me and another guy. When we had sex ed days, for the gender split activities he and I would sit at the back of the girls' group. We were just on our phones or doing other stuff, because they didn’t know what to do with us.”

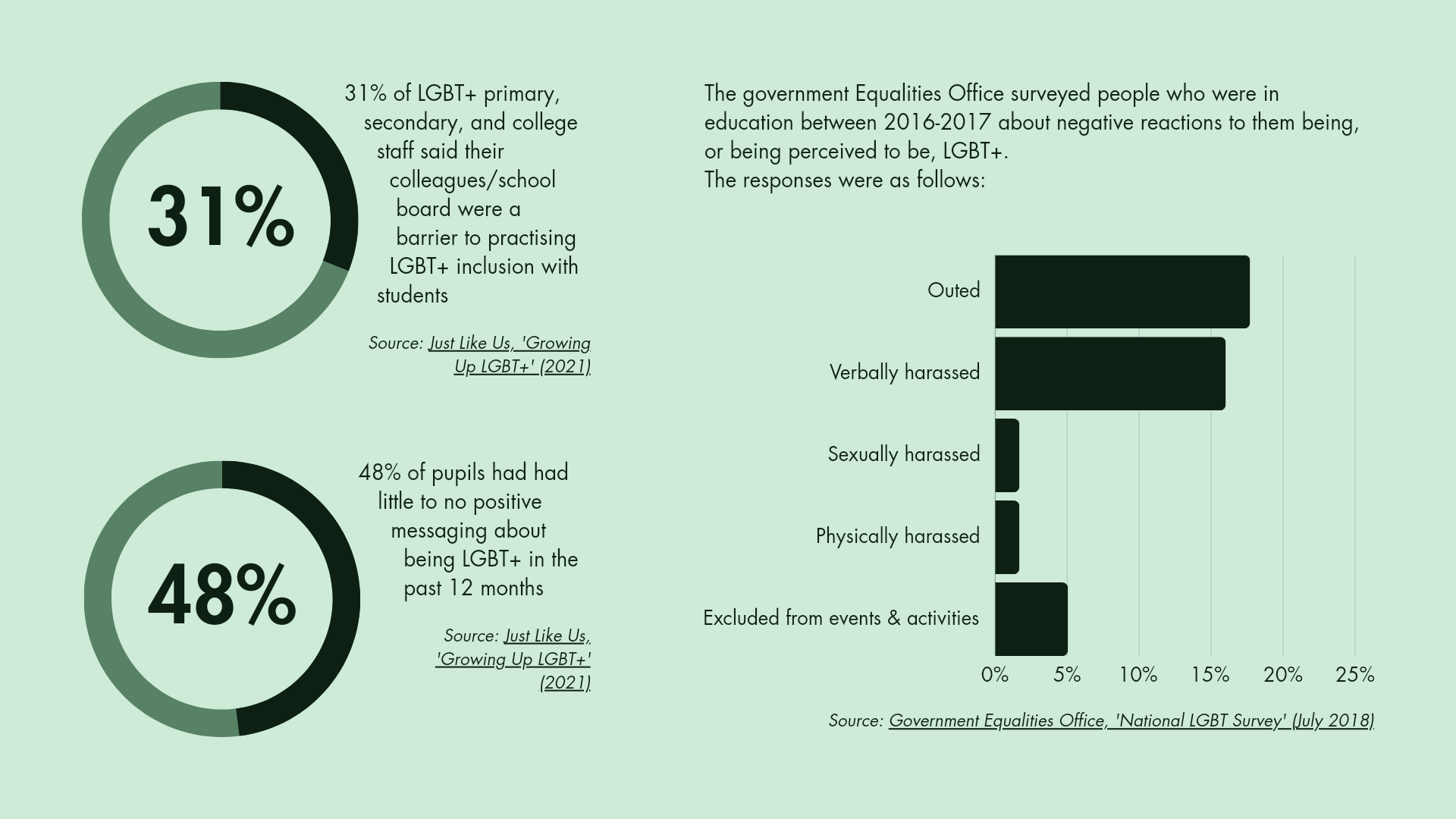

Just Like Us' 2021 survey also found that mental health issues were far more common among LGBT+ students. They were more than twice as likely to suffer from depression, panic attacks, self-harm, eating disorders and alcohol or drug dependence. They were also more than twice as likely to have contemplated suicide compared to their non-LGBT+ classmates.

Educational reform, moral panic

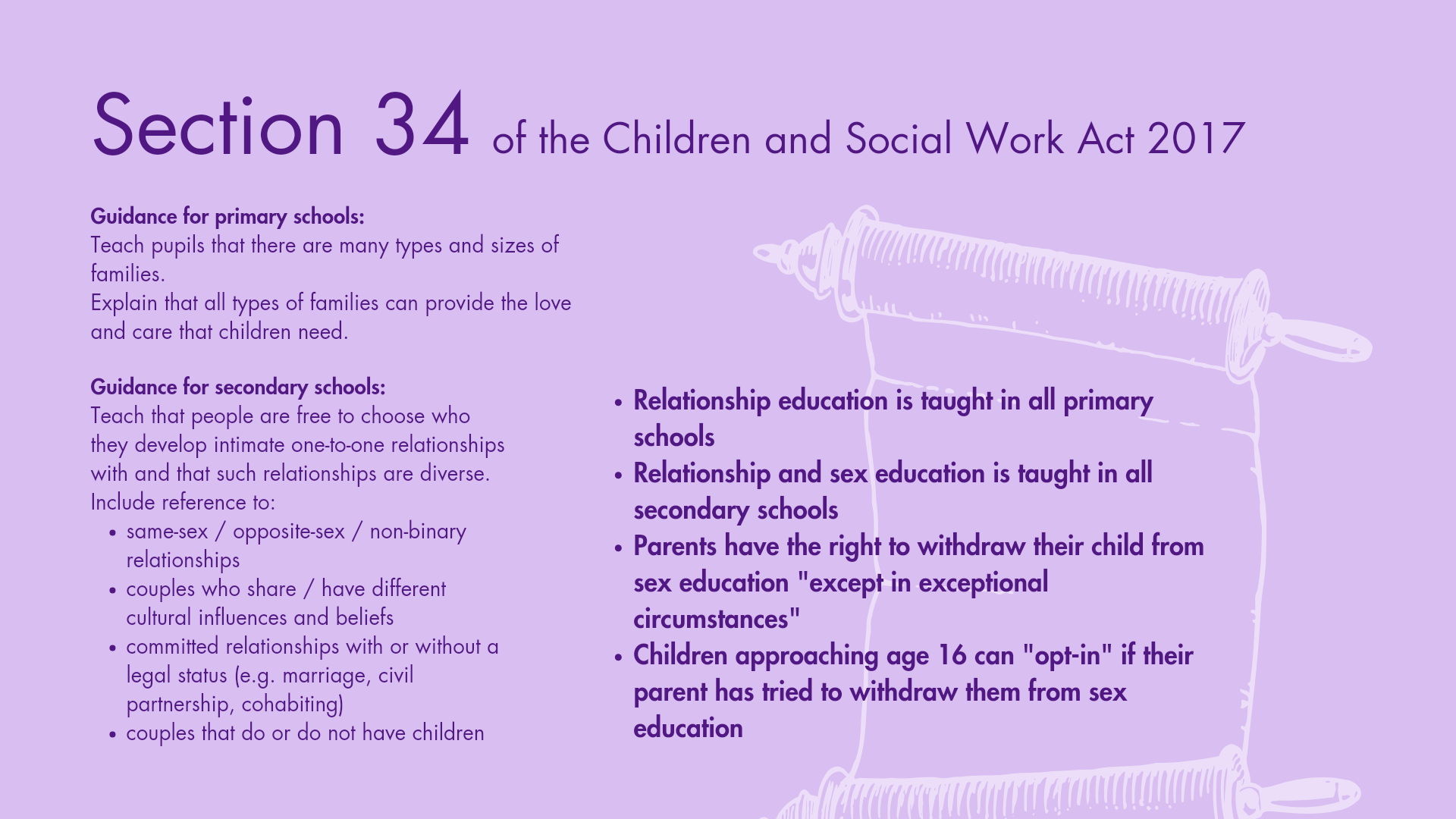

Teaching about LGBT+ identities and relationships became mandatory for UK schools in September 2020, when Section 34 of the Children and Social Work Act 2017 came into force.

This legislation formalises and expands the work of LGBT+ History Month, which was introduced by Schools Out UK in 2005. In an article, Dr Dahms said LGBT+ History Month follows the example of Black History Month and aims to undo the damage of Section 28.

However, the moral panic that surrounded the passage of Section 28 has not been lost to time.

In 2018 then-prime minister Theresa May first promised to introduce a ban on conversion therapy, a practice by which people attempt to 'cure' LGBT+ people. This can include processes like counselling, forced ingestion of 'purifying' substances, ‘corrective’ rape and exorcisms. Such a ban is yet to be passed, while ministers and activists have disagreed over whether the trans community should be covered by protections.

On January 16th 2023 the government used Section 35 of the Scotland Act 1998 to block the passage of Scotland's Gender Recognition Act, which would allow trans people to legally change their gender without a formal dysphoria diagnosis. Receiving such a diagnosis is difficult; the BBC has reported that some trans people have had to wait seven years for their first NHS assessment.

In their Conservative Party Conference speeches in October, prime minister Rishi Sunak and then-home secretary Suella Braverman used pejorative language about trans identities.

Protest at Downing Street, April 10th 2022. Credit: Caitlin Chatterton

Protest at Downing Street, April 10th 2022. Credit: Caitlin Chatterton

This negative political discourse surrounding LGBT+ issues has been matched by increased calls to monitor inclusive sex and relationship education in schools.

The introduction of compulsory inclusive education in 2020 followed high-profile protests outside Anderton Park primary school in Sparkhill, Birmingham the previous year. Parents said the school, which taught a largely Muslim community, was pushing content at odds with their faith.

The High Court permanently banned protests outside the school in November 2019. High Court judge Justice Warby said: “They have suggested the school is promoting homosexuality when it is not.”

In March and October 2023, secretary of state for education Gillian Keegan echoed some of the protesters' arguments when she wrote to headteachers, demanding they make sex education learning resources available to parents.

Under current guidance, parents have the right to withdraw their children from sex education in most cases. However, children approaching 16 years old can 'opt-in' regardless of their parents' wishes, and children cannot be withdrawn from relationships education.

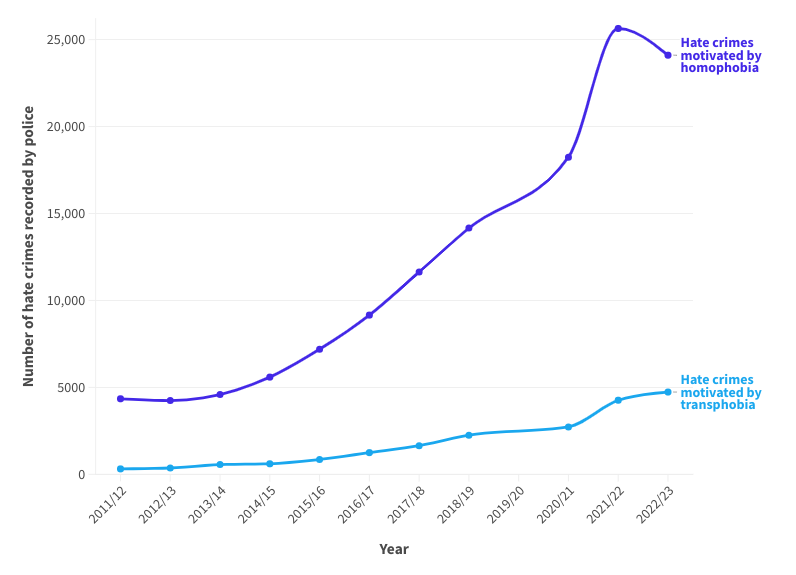

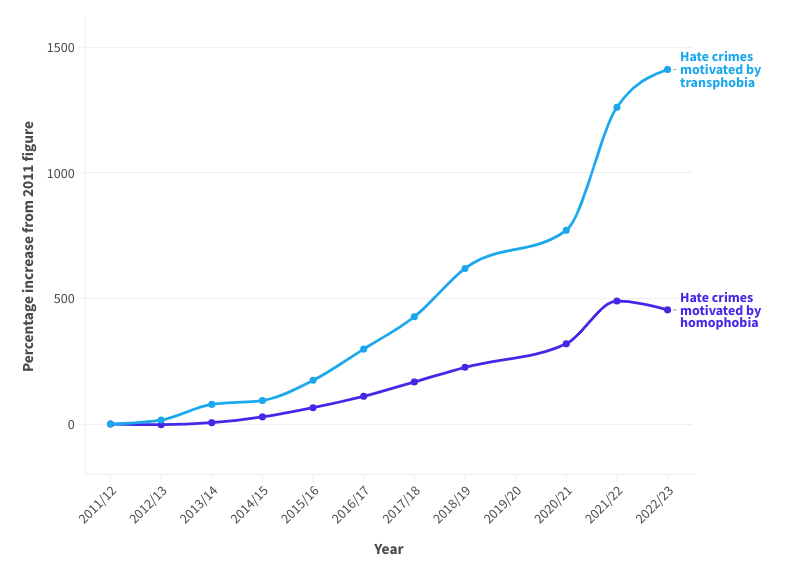

Data gathered from Home Official Statistical Bulletin: Hate Crime, England and Wales, 2017/18 (2018) and Home Office Official Statistics: Hate Crime, England and Wales, 2022 to 2023 second edition (2023)

Data gathered from Home Official Statistical Bulletin: Hate Crime, England and Wales, 2017/18 (2018) and Home Office Official Statistics: Hate Crime, England and Wales, 2022 to 2023 second edition (2023)

Just Like Us

Credit: Isaac

Credit: Isaac

Credit: Zoya Soni

Credit: Zoya Soni

Since its founding in 2016, the charity Just Like Us has trained its ambassadors (LGBT+ people aged 18-25) to go into schools and deliver talks to increase awareness and visibility around LGBT+ experiences. While they do not teach sex education, the ambassadors open with their own stories of growing up LGBT+, before discussing various definitions and opening the floor to questions.

Just Like Us ambassador Isaac said: “It’s funny we bring up Section 28. Obviously it’s 20 years since it was repealed, but even to this day you see the lasting effects on teachers: even if they are technically able to speak about being gay or trans, or LGBT+ in general, they don't seem to have the words to teach it.”

Fellow ambassador Zoya Soni agreed: “A lot of the time [teachers] might not be aware of the issues or the definitions that we’re talking about. I do think there’s some learning for them as well; sometimes they ask us questions when we finish our talk, which is really nice because it shows that they care about this issue and want to learn more.

“I once did a school talk where there was a student in the front row and they seemed quite nervous: they were fidgeting and their leg was shaking. At the end of the talk, when all the students left, one of the teachers mentioned that to us. It was really nice to see that the teacher picked up on that and cared about the student.”

The moral panic that frequents the news is not obvious in the schools Just Like Us visit. Isaac said: “You’ll be surprised – or maybe you won’t be surprised – to learn that a lot of the time we go into schools and they’re already very well clued up. It depends on the type of school and type of pupils that we’re talking to; really, the schools that we need to be in are the schools that don’t want us there.

“I might go to a school that has never had any LGBT+ education, which was certainly the case for me and is unfortunately still the case for a lot of schools in the UK. You can tell that they’re a bit more hesitant, or they’re just trying to wrap their heads around things. The kinds of questions that you’ll get will usually be of a very curious nature or exploratory, but for the most part it’s usually a very positive outcome and learning experience for everyone.”

Zoya said: “The reactions can vary. I think it also depends on the age of the students. Sometimes the younger students tend to be more engaged and more interactive so they’re more likely to ask questions. Other times the older students, for example sixth form students or year 10 or 11, will tend to be more quiet.

“Sometimes there’s the person that asks a question to make other people laugh, but we are trained to answer them in the correct way. For the majority we get positive reactions.”

"Allyship falls on everybody to make a safe space for everyone, so that’s why I decided to start volunteering.”

Just Like Us ambassadors begin their school talks with discussions of their own experiences growing up LGBT+. Zoya uses her story to discuss moving from India to London, the term 'queer', and the privilege it is to be a part of the community.

Zoya said: “I am really grateful for finding Just Like Us as having something like it when I was in school would have helped a lot. Now because of joining Just Like Us; I have gained self-acceptance of my identity and feel more confident!

“As the anniversary of Section 28’s repeal is coming up, it reminds me of the reasons why charities such as Just Like Us are essential for young people.”

Isaac also shares his experience of growing up, and why he decided to become a Just Like Us ambassador.

Isaac said: “What’s quite funny is it turns out so many people at my old school, and even in my town, were gay or were trans, but obviously we hadn’t been operating in an environment where it felt safe to be open about that. We all had to leave to learn that about ourselves or to be open about it.

“It’s all around us all the time. It’s just about how safe you feel, and that’s the whole point of this: making everywhere, hopefully, safe and comfortable.”

Mosaic Trust

Just Like Us isn't the only charity working to increase LGBT+ education and visibility among young people. Founded in 2001, Mosaic Trust works to provide young LGBT+ people with resources, activities and services to educate and inspire them.

Mosaic Trust executive director Łukasz Konieczka said: “Sadly we find that very few of our members learn anything about the LGBT+ community; its history, activism and culture, so we have to plug that gap. It is critical for identity formation to know where one’s roots are.

“The LGBT+ community has an amazing past, full of fabulously powerful characters, events that resist the oppression, and creative and innovative ideas both for self-expression as well as community organising.”

"It is critical for identity formation to know where one’s roots are."

Mosaic Trust provides mentoring, online counselling, and work experience schemes, as well as organising residential trips and annual events like Pride Prom and Homoween.

Łukasz said: “They learn about the past struggles, our activists, and people who persevered through adversity. They build confidence, develop a network of friends and grow.

“Having a community and experiencing a feeling of belonging is critical to growth and development of any teenager and it is no different for LGBT+ teens.

“Having a safe space to connect with LGBT+ mentors who are here to provide friendly advice and guidance is often the only place where conversations around relationships, peer pressure, and career paths can happen.”

20 years of progress?

Section 28 was repealed 20 years ago, but it took 17 years for LGBT+ inclusive sex and relationships education to become compulsory in schools.

Charities like Just Like Us and Mosaic Trust are continuing to work with young people to increase visibility and education.

Credit: Caitlin Chatterton

Credit: Caitlin Chatterton