Ultra-Fast Fashion, the paradox of Gen Z

A young woman faces the camera holding an enormous plastic parcel, she tears it open and releases a plastic waterfall of smaller bags onto her floor. These bags all contain an individual item which she then proceeds to try on. Pink top, red top, orange top, white top, black top, green zebra-striped top, black top, pink top, red top, corset, green top, zebra top, white top. “literally not even half of my package”, the caption reads, “but I got tired of trying things on”.

This video isn’t especially remarkable. It follows an identical format to other “haul” videos made by young women on the social media platform TikTok which involve trying-on new clothing purchases. But it perhaps acts as a microcosm for the internal battle Gen Z appears to be fighting with itself. The video has 1.5 million likes and more than 74,000 saves (most likely so people can refer to it for inspiration for future purchases).

And yet, it appears that people can’t, or won’t, stop. The hashtag “haul” has 20.2 billion cumulative views on TikTok. This number is growing by the day.

But all of the highest rated comments in the comment section are disparaging:

The clothes this young woman was trying on were from Shein. #SheinHaul boasts 5.4 billion views in its own right. Shein is a Chinese e-commerce company and was recently valued at $100 billion, making it the third most profitable start-up in the world, worth more than fashion giants Zara and H&M combined. This company, and others like it such as UK-based Pretty Little Thing, is the newest iteration of fast-fashion: ultra-fast-fashion.

Credit: WikiMedia Commons, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en

Credit: WikiMedia Commons, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en

But what actually is ultra-fast fashion?

In its essence it's similar to fast fashion, which follows a mass-production, mass-consumption business model in which low prices are paired with rapid trend turnover. Rather than following the traditional high fashion calendar, fast fashion brands race through micro-seasons meaning they share new clothing “drops” more regularly.

Ultra-fast fashion, as the name suggests, is the same but at top speed. These companies only operate online, so unlike more traditional competitors they don’t have to bulk order styles to fill brick-and-mortar stores. They reach their target audience directly through their screens.

CEO of Shein, Molly Miao, proudly told Forbes that the “new-in section” of Shein is updated with 700 – 1000 new styles every day. At the time of writing there are 70, 632 products under “Women’s Dresses” on the site. Prices start as low as £2.49.

But what is driving this insatiable appetite for new clothes?

In the online world of Instagram and TikTok, life is curated into perfect little squares. Gen Z users spend an average of 2 hours and 43 minutes a day scrolling on social media and favour Instgram and TikTok. On Instagram particularly “outfit repeating” is seen by many as a cardinal sin.

“my problem is that repeating an outfit makes me cry so I spend $$$ each month on new clothes it never stops lol” user @fairydeema lamented on a haul video. This comment was liked 879 times.

Izzy Manuel (@izzy_manuel) is a London-based sustainability influencer. Her Instagram features pictures of her wearing (and re-wearing) fun, often brightly coloured, clothes. But this wasn’t always the case.

“When it comes to re-wearing there’s a huge shame. When I was at uni there was a massive stigma of you couldn’t wear the same thing twice when you go out because that would be weird”, she says.

Manuel advocates what she calls imperfect sustainability. She admits that when she first started out being more sustainable in 2020, she didn’t suddenly drop all her previous habits. She says: “I couldn’t help but shop at H&M every now and then or go “oh that Zara piece is so nice”. But I’d go “I’m not going to buy as much this time”. She compares being sustainable to learning to ride a bike; at first you might be rubbish but as you learn, you improve.

Today, she is a proud outfit repeater.

Izzy Manuel re-styling Elizabeth Whibley X Yak trousers. Credit: Lucy Ranson

Izzy Manuel re-styling Elizabeth Whibley X Yak trousers. Credit: Lucy Ranson

Credit: Lucy Ranson

Credit: Lucy Ranson

Credit: Lucy Ranson

Credit: Lucy Ranson

Influencers have a role to play in shaping people’s habits, as they are often the human mannequins for ultra-fast fashion brands. Online, influencers almost never wear an outfit twice. Instagram's “shopping” feature means users can purchase a garment modelled by an influencer in a matter of taps. One in five fast fashion shoppers say they feel pressure to have the latest style because of social media (ThredUp 2022 Report).

Influencers’ reach can be huge: Molly-Mae Hague, for example, runner-up on Love Island 2019 and ultra-fast fashion brand Pretty Little Thing’s Creative Director, boasts 6.4 million Instagram followers.

Hague's online presence strikes a balance between aspirational and relatable. She goes on glamourous holidays to Dubai but wears a Pretty Little Thing dress which followers can purchase too.

“With influencers, it feels like, with a little help and a little of their product, we could be (like them)”, says Naomi Fry in the New Yorker.

Emma Håkansson is an Australian activist, author and founder of non-profit Collective Fashion Justice. She says that when it comes to the role of influencers in fast fashion marketing, much of what brands want people to feel is FOMO, fear of missing out.

“The whole ‘it girl’ concept is rooted around wealth and a need to obtain certain things (certain products, garments, body types) to be popular and stylish”, she explains.

“We need creators on these platforms to celebrate their personal style – we don’t need to buy into every new micro-trend.

“Fashion is more fun and creative when we find our own tastes and curate a wardrobe slowly, and mindfully, over time.”

In addition, Håkansson explained that this “wear-it-once” mentality perpetuated online means that consumers forget the resources, skill and labour involved in the creation of that item. According to market research firm Mintel Data, 64% of British 16- to 19-year-olds admit to buying clothes they have never worn.

“People need to see clothing as a long term investment – we shouldn’t be buying garments that we think we’ll only wear a few times, but as things that we know will make us happy for years to come, that we’d be happy to repair and care for.”

Credit: Hardie Grant Publishing, Collective Fashion Justice

Credit: Hardie Grant Publishing, Collective Fashion Justice

Emma Håkansson, Collective Fashion Justice Founding Director. Credit: Jackson Loria

Emma Håkansson, Collective Fashion Justice Founding Director. Credit: Jackson Loria

Jemma Finch, Stories Behind Things CEO

Jemma Finch, Stories Behind Things CEO

A Stories Behind Things clothes swap event encouraging a more circular approach to shopping.

A Stories Behind Things clothes swap event encouraging a more circular approach to shopping.

Repairing and caring for clothing is something which Jemma Finch, founder and CEO of sustainability platform Stories Behind Things, champions.

She explained that the key to solving the issue of rampant consumption of fast-fashion is re-framing the concept of “newness”. “I think with sustainable fashion there's this narrative of you can't have anything new and you can't wear fun expressive clothes. It all has to be beige and made of hemp”, she says.

I think that's an unfair representation of the sustainability space because you can rent clothes, you can swap them, you can repair, or upcycle. Clothes don’t have to be new from a store with a label on them.” Indeed, Finch organises clothes swaps around London for people to bring and trade clothes.

So what is Finch’s remedy for fast fashion pressure from social media? Curate your online world. She says: “It's important to unfollow people and companies who are not aligned to your values and what you want to see every day. Nowadays we pick up our phones before we talk to our closest friends or family. So make sure all of that information that you're receiving in the first five seconds after you wake up is in line with the life that you're trying to live day to day.”

But is there an inherent friction between the idea of being “sustainable” while also “consuming” when consumption is bad for the planet?

“Ultimately yes”, says Brooke Bowlin, artist and founder of sustainable fashion business 251 Thrift (@secondhand.sustainability). “You cannot replace a Shein haul with a sustainable or second-hand fashion one. We need to shop less, period. The product you buy, even if it’s sustainable, will still have an impact”.

Second hand items displaced nearly 1 billion brand new clothing purchases 2021. 80% of consumers say they’re buying the same or more second hand apparel items, according to a recently released report by ThredUp.

But Bowlin warns of not fully addressing the compulsive mindset which leads to purchasing. The discontent over repetition of outfits will persist if you buy second-hand in excess.

According to a recent global survey by Deloitte, 90% of Gen Zs and millennials say they are making at least some effort to reduce their own impact on the environment. 64% of Gen Zs say they would be willing to pay more for an environmentally sustainable product.

Fashion retailers seeking to entice this younger audience know they are a climate-conscious cohort. As a result they are keen to show-off their eco-credentials in a bid to woo them. “Conscious”, “ethical”, “planet-friendly”, “sustainably-sourced” are words often used to describe garments or entire lines.

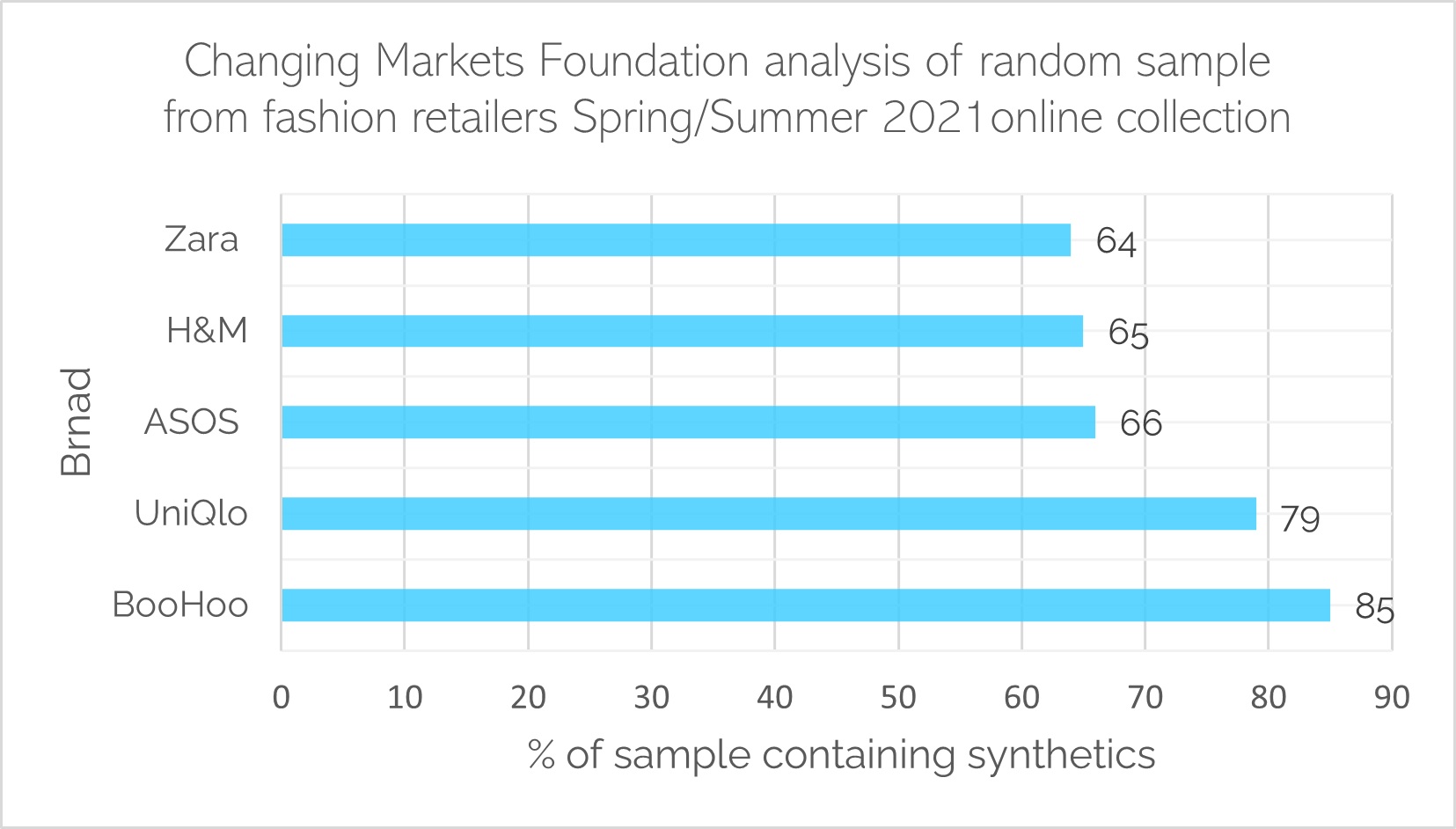

However, it's often unclear how trustworthy these claims are. Synthetics Anonymous, a 2021 report by Changing Markets Foundation, found that H&M’s Conscious Collection, which is promoted as more eco-friendly, actually contained a higher percentage of synthetics than its main collection (72% vs 61%).

Data source: Changing Markets Foundation, 'Synthetics Anonymous: fashion brands’ addiction to fossil fuels', June 2021

Data source: Changing Markets Foundation, 'Synthetics Anonymous: fashion brands’ addiction to fossil fuels', June 2021

"READY FOR THE FUTURE" is ultra-fast fashion brand BooHoo's take on sustainability. This line manufactures some garments from recycled polyester instead of the virgin material. However, Changing Markets Foundation argue in their report that recycled polyester is “a false solution – and a far cry from a truly circular business model.”

The majority of recycled polyester is made from the most common kind of light-weight plastic bottles (PET). Critics argue that diverting plastic bottles from a closed-loop, bottle-to-bottle recycling system is not better for the environment. If these bottles are turned into cheap fashion garments it's potentially more likely they'll end up in landfill. Changing Market Foundations argues that, “This prompts questions about why the industry is using PET bottles instead of the millions of tonnes of textile waste going into landfill?”

Credit: Omnes

Credit: Omnes

Smaller brands tend to be more transparent about their supply chain. Omnes is one example. It’s a London-based women’s fashion label on a mission to bring sustainable fashion to the masses, with comparatively low prices to other other eco-friendly brands. The website gives detailed explanations of where garments are made, how much garment workers are paid, how much holiday they’re given and the origins of the fabric they use.

An Omnes spokesperson said that all brands should be showing this kind of information: “There needs to be a huge attitude shift towards suppliers, factory workers and garment workers in general and full transparency of the hundreds of hands each garment touches.”

Omnes’ advice for spotting greenwashing? “When something sounds vague or fluffy that’s because it is. If there is no solid example or fact that they are using to back up statements, I personally would not believe it.”

ITV reality dating programme Love Island has been synonymous with fast fashion. 43% of its viewers are under 30. For three years fast-fashion brand I Saw It First was the official sponsor and contestants often partnered with similar brands once they left the show.

This year marks a change as Love Island 2022's official partner is eBay. Islanders are dressed in pre-loved items and viewers can peruse similar "Islander inspired" items on eBay. The partnership presents, “the chance to promote individualism over one homogenous dress code”, says Alice Newbold in British Vogue.

Indeed, only time will tell if those currently in the ITV villa will shun offers from fast-fashion retailers when the show finishes. But this move away from ultra-fast fashion is a step, albeit a small one, in the right direction.

Image Credits

Nesa Dump Rubbish, credit: The Donkey Sanctuary, Flickr

Laundry Dry Hang, credit: Pixabay

Global Climate Strike London, credit: Garry Knight, Flickr

Plastic bottles, credit: Pixabay

Graphics, Antonia Lenon designed on Canva