A Gentleman's Game

The rise of women's rackets in a sport dominated by men

An empty rackets court is an eerie place. Used to balls streaming around the court at one hundred miles per hour, the large black concrete walls sit vacant, and quiet.

Peppered with white streaks, and split by red lines, the thick slate and terracotta structure looks less like a court and more like a historical monument. And there aren’t many left.

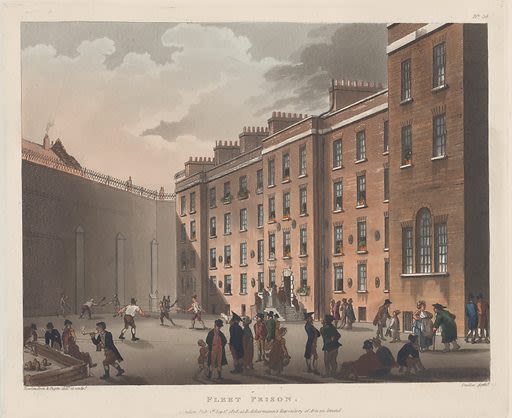

The game first saw the light of day as the sun streamed in from above the walls of London’s 18th-century debtors' prisons: Southwark’s The King’s Bench and Farringdon’s The Fleet.

Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Prisoners awaiting redemption idled away their time by playing a yet to be coined sport, rackets. The fundamentals are easy to grasp: the simple action of hitting a ball against a wall with a wooden racket. Just make the racket head small, and the ball smaller.

Soon enough the skilful game took hold in the empty courtyards of pubs across the capital, but as the popularity of this open court plan diminished, as did its future transcend from public spaces to the private ones of clubs and schools.

And as the British Empire was gripped by colonialism, hundreds of courts were set up in places such as Hong Kong, India and Buenos Aires. Today courts remain in Canada, the US and the UK only.

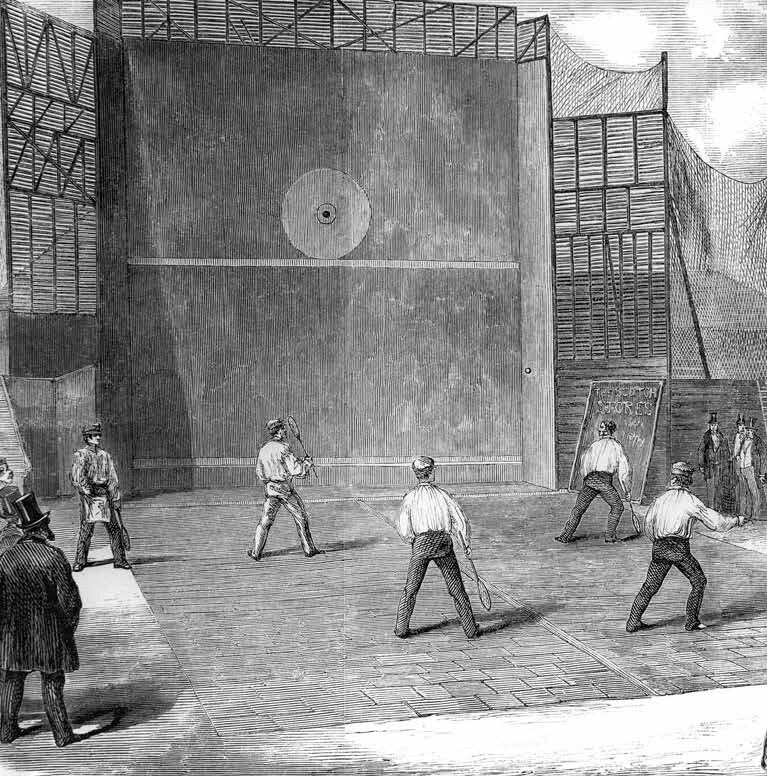

Credit: The Neptune Book of Tennis and Rackets

Credit: The Neptune Book of Tennis and Rackets

From its grubby origins, to the elitist fraternity that now houses this ancient forerunner to squash and follower of 'real tennis', a court sport favoured by Henry VIII, the game has barely changed.

It is still one of the fastest and most dangerous ball games, and spectator sports, in the world. The crowd still have to duck as balls come hurtling at their heads in the open viewing gallery.

Two or four people still attempt to control a small, white ball around the same size as a golf ball as it tears around the four walls of an indoor court at up to 180 mph. And they still do it with what look like primitive tennis rackets.

Except for one thing: now women play.

"Within whose ample Oval is a Court, Where the more active and robust resort, And glowing, exercise a manly Sport. While those with Rackets struck the flying Ball, Some play at Nine Pins, Wrestlers take a Fall."

Poem from 'a Gentleman of the College', The Fleet, 1749

Rackets games are played first to 15, with only the server able to win points. The receiver must win the point to get into the service box.

The server serves from the service box on either side of the court. In the US there is only one serve allowed, but in the UK you have a second serve.

The serve must go above the top red line whilst groundstrokes must land on the wall above the bottom red line known as the 'tin'.

The ball must only bounce once on the floor, but can bounce off any of the walls, leading to extensive use of angled shots and boasting off the walls.

Trailblazer

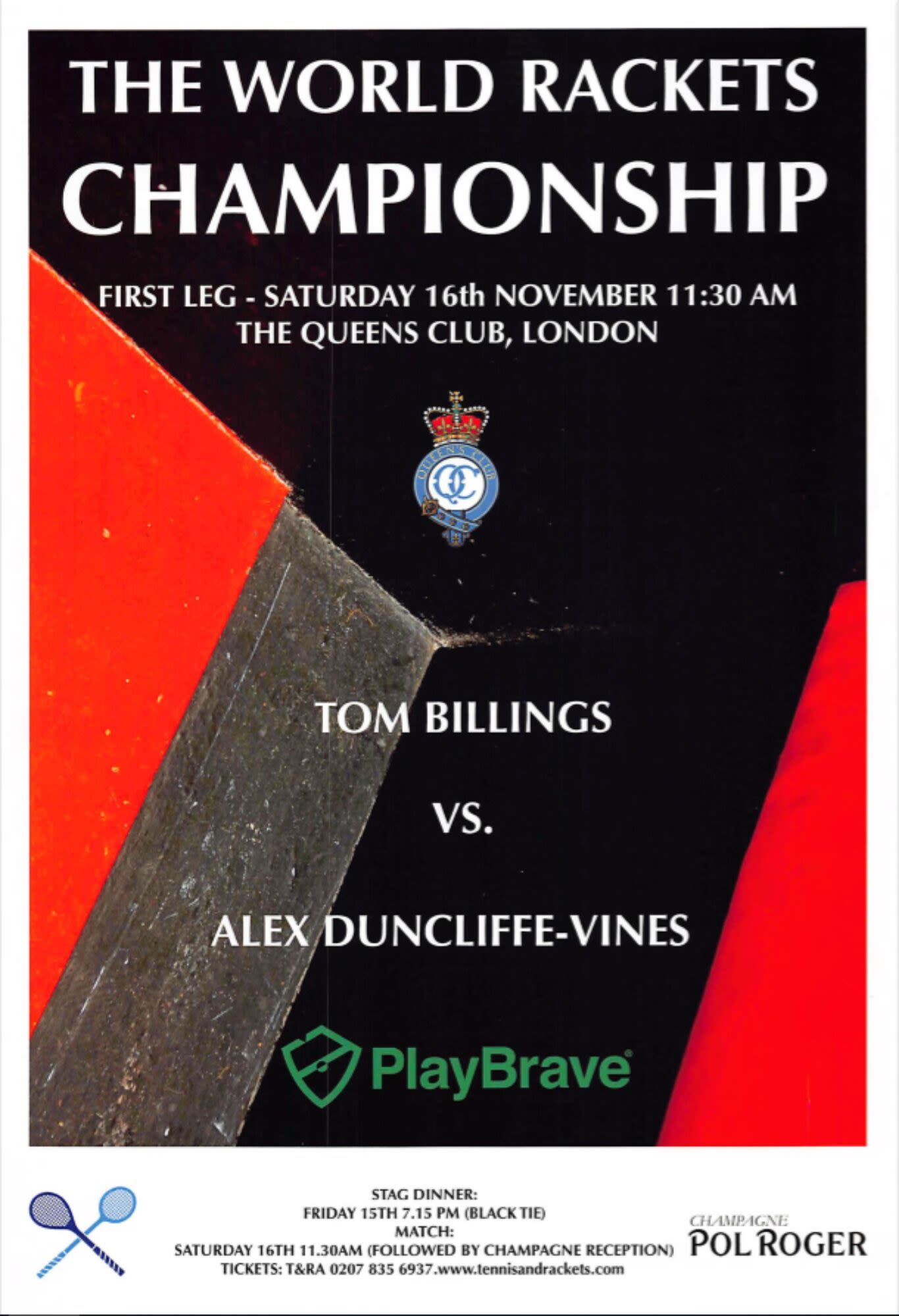

In London rackets is headquartered near Hammersmith at the Queen’s Club, known for hosting its namesake ATP Tour 500 tennis tournament.

This was the stage for the rise of Lea Van Der Zwalmen, women’s rackets’ trailblazer and champion of the world.

Van Der Zwalmen said:"It's such a thrill when you smash a backhand down the line.

"I love the adrenaline of the game because its so fast and furious.

"There's no time to think it's just based on instincts."

Born in Leuven, Belgium and raised in Toulouse, Van Der Zwalmen played ten years of international squash for France before trying rackets.

She said: "Until 2008 women were not allowed to play because it was deemed too dangerous.

"I just rocked up to play and gradually I was able to prove to men that women could play at the same level and it was not too dangerous.

"The level is just getting higher and higher every year. The game has grown massively and I'm looking forward to seeing the game continue to grow more in the future.

"This is perhaps my greatest pride, let alone being world champion. Just being part of this new generation of players is incredibly satisfying."

The Belgium-native first started playing rackets at Bristol’s Clifton College under the tutelage of rackets professional Reggie Williams.

Chris Davies, CEO of governing body the Tennis and Rackets Association (T&RA), said he recalls the moment Reggie discovered her.

He said: “You just recognise talent immediately when you see it.

“Reggie said to me Chris you’ve got to come see this player, she’s absolutely fantastic.

“She was such a wonderful player with the purest, sweetest backhand.”

At the time, women’s rackets was in its infancy stage and only a few women played.

In rackets, only the server can win points, with the returner having to win the point to win the opportunity to serve.

Whilst in the men’s game you can often watch minutes-long rallies wherein the players chase the ball just as much as it chases them, women’s rackets began largely as a serve and return game.

In a game of slice and cut, where groundstrokes can be played off any of the walls and fitness is everything, Van Der Zwalmen’s supreme serve and natural sporting prowess cut straight through early career opponents.

In the first Ladies World Singles Championship in 2015, van der Zwalmen took on former Real Tennis World Champion Claire Fahey. And beat her two sets to one.

She hasn’t lost since.

Leading the Way

When Chris Davies spoke of women’s rackets, he spoke of two time periods: before Lea, and after.

This time before Lea, or BL, was punctuated by a few talented sportswomen from the worlds of tennis and real tennis including Claire Fahey and Alex Brodie.

Having only started playing around in the late 2000s, soon enough women had created a new style of play.

As early player Sally Jones said: "No one was trying to pretend we're stronger than the men.

"It's a different game entirely."

Now the women's game is growing at a rapid pace, with entry into competitions increasing each year and the number of women playing proliferating to never-before-seen levels.

In 2011 there were nine entries to the first ever Ladies British Open. Ten years later this number has more than doubled.

At the forefront of that growth is Tara Lumley.

Lumley, 28, was drawn to the game through its counterpart: real tennis, and has since become British Open Doubles and Singles Champion.

The natural sportswoman, who is also a life sciences consultant at L.E.K. is one of the most dominant players on the circuit, with a strength and serve to rival that of the men.

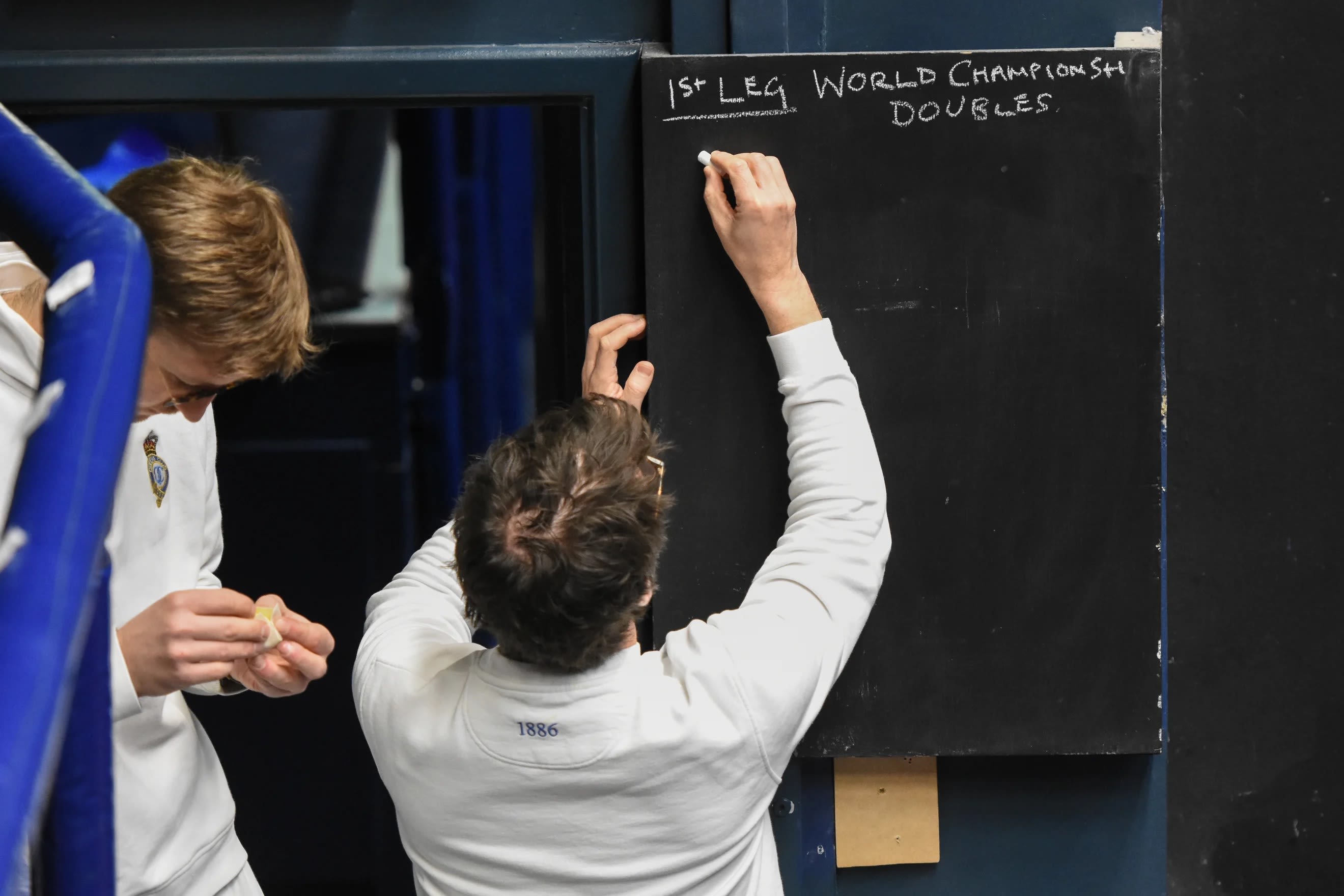

Lumley and partner India Deakin even beat Van Der Zwalmen and her partner Louisa Gengler-Saint in the first and only World Doubles Championship in March 2020.

She said: “When I first played rackets I was instantly hooked.

“I love the fast pace of the game and testing my reactions; it is probably the most difficult game I have encountered and I enjoy the challenge.

“We have seen great developments in the breadth and depth of the game - both in terms of new players but also the overall standard.

“I think this is only going to grow and expand over the years.”

Another player heightening standards within the sport is British Open Singles Champion Georgie Willis.

Having started playing on an often empty court on Hayling Island with her siblings, Willis has become a quintessential member of the rackets community.

The 24-year-old law student said: “I’m really excited to see where women’s rackets goes in the future.

“There’s such a good community around it now, I’ve made so many friends through rackets so they keep me playing.

“I also just love how fast it is, how instinctive it is. It’s just a great game.”

World Ranking Points of the top 10 women's rackets players

The Supporting Act

Within the Gentleman’s clubs, the women’s game has not been self-founded. Instead, it has been helped along the way by a group of eccentric, and forward-thinking men.

From Howard Angus, whose wife donated her name to the U18 National Girls Cup, or Paul Danby, who helped establish a court at Hayling Island, there have been many supporters to the game.

Angus, who spent most the 1970s as amateur rackets or real tennis champion, was in the gallery for November’s British Open Doubles final.

He said: “I think the momentum is unstoppable now.

“We’re going in the right direction, the average standard keeps going up and the standard at the top is brilliant.

“It is clear that today's match was the highest standard we’ve ever seen in women’s rackets.”

Ben Bomford, head rackets professional at the Queen’s Club, is excited about the future of the women’s game.

Bomford said: “Women’s rackets was such a hole, and now its building.

“We’ve seen so much growth over the last few years, and we just need to keep building on that.

“Rackets is such a brilliant game, there’s just something about it. It’s unique, it’s quick, it’s difficult, it’s challenging and it’s frustrating.

“It’s like golf, you play a bit and get better and then you don’t play and you take steps back. But it’s also so rewarding.

“Most people that play, they come on court and play for an hour and they’ll probably hit at least one great shot that makes it all worth it.

“You give a lot to any sport you play, but rackets is a sport that gives a lot back.”

Queen’s is the main place where rackets is played beyond school, and takes centerstage in developing the game.

One way which its doing this is through mixed rackets. Men and women get together and play in pairings of varying talent, levelling the playing field.

Bomford said: “It’s great for the women to play with men who perhaps hit the ball harder and a bit more aggressive at times.

“Hopefully it will increase their understanding of the game and give them more confidence because in any sport, playing with someone better than you, makes you play better.

“Mixed tennis has been popular for years and it’s great for the men to open their eyes to developing the ladies game and not be so male-centric.”

One man has been crucial in pushing the development of mixed rackets.

Amateur player Julius Manton-Jones thinks the distinct game is part of the future of women’s rackets.

The 25-year-old IBM AI sales specialist said: "There is a vast number of untapped opportunities to improve the women's game. One way is through mixed doubles.

"Getting a feel for how rackets and especially doubles works, it's all about playing with a few experienced people who move in the right way. You learn to move around the court and understand the dynamics which take place.

"I only got better at playing with people who are better than me. If they had the mindset of thinking why am I playing with someone worse than me I wouldn't have got to where I have so far.

"I think the boys find they enjoy it more than they thought they would, it goes both ways and it helps build the community.

"There are lots of good women's rackets players out there but did they come and play as regularly as they do now? Probably not.

"The impact of mixed rackets on the sport is definitely visible. It's clear we've got a more active playing community in the last six months."

Mixed doubles is on the rise. Rory Giddens and Georgie Willis (left) beat Tara and John Lumley (right) in the Andrina Webb Mixed Doubles at Queen's Club. Credit: T&RA

Mixed doubles is on the rise. Rory Giddens and Georgie Willis (left) beat Tara and John Lumley (right) in the Andrina Webb Mixed Doubles at Queen's Club. Credit: T&RA

The rise of women's rackets complements the established men's game. Credit: T&RA

The rise of women's rackets complements the established men's game. Credit: T&RA

Julius Manton-Jones organises mixed nights that help everyone benefit from the game

Julius Manton-Jones organises mixed nights that help everyone benefit from the game

The Future

Rackets has a few fatal flaws. Expensive, exclusive and extremely difficult, it’s not a game made for 21st century, or Generation Z.

But with the sport giving new space to female players, and Queen’s taking part in a number of outreach programmes in the local community of West London - the game is finally modernising.

And top players like Van Der Zwalmen, Lumley and Willis are inspiring new generations to keep the game alive.

Cesca Sweet started playing rackets five years ago at school, and quickly went on to win national singles and doubles competitions in rackets and real tennis.

In May this year, Sweet reached the final of the singles world championships and battled Van Der Zwalmen for the title. She was 17.

The university student said: “When I played in the final against Leah, I have to admit I was a bit starstruck.

“Playing against somebody who is such an amazing player, and who has been world champ for so long, it felt daunting.

“But my game did improve on the day and I look forward to playing her again sometime in the future.

“I absolutely intend to keep playing because I don’t yet feel I’ve reached my full potential and it’s great to be part of a wonderful sport with such friendly people to play with.”

Inspiring students to keep playing rackets is the number one priority of Cheltenham College rackets professional Mark Briers.

Briers is almost single-handedly responsible for the growth of school-level women’s rackets, having coached countless girls through national competitions to a high playing standard.

He said: "Rackets' achilles heel for generations has been about just winning things. But so many of these winners haven't carried on playing and don't give anything back to the sport.

"But if you enjoy the sport, it doesn't matter what sport it is or what level you're playing at, you'll play it because you enjoy it and you're putting energy back into the sport.

"I don't invest my time in girls rackets because we're going to win things. I watch how they play it and it gives me an immense sense of pride because they play with a smile on their face.

"Having early success with the boys and championships helped me establish myself but it didn't make me a better coach.

"Girls' rackets and women's rackets has made me change more than anything - as a coach and as a person.

"Long may it continue and grow."

Featured photos credit: The Queen's Club, the T&RA and Tim Edwards. Poll photos via Unsplash

18-year-old Cesca Sweet is the newest star in the world of women's rackets. Credit: T&RA

18-year-old Cesca Sweet is the newest star in the world of women's rackets. Credit: T&RA

Cesca Sweet (left) pictured with World Champion Lea Van Der Zwalmen (centre) and T&RA CEO Chris Davies. Credit: T&RA

Cesca Sweet (left) pictured with World Champion Lea Van Der Zwalmen (centre) and T&RA CEO Chris Davies. Credit: T&RA

Sweet vied for the world title at just 17 years of age, the youngest challenger in rackets history. Credit: T&RA

Sweet vied for the world title at just 17 years of age, the youngest challenger in rackets history. Credit: T&RA

"There is no game, perhaps, not even cricket itself, which combines so well skill with so much bustle. The racket player is always on the move, standing still is entirely out of the question."

Pierre Egan, Book of Sports and Mirror of Life Number XV: The Game of Rackets, 1832