THE INSIDE STORY

You have to see it to be it, as the saying goes.

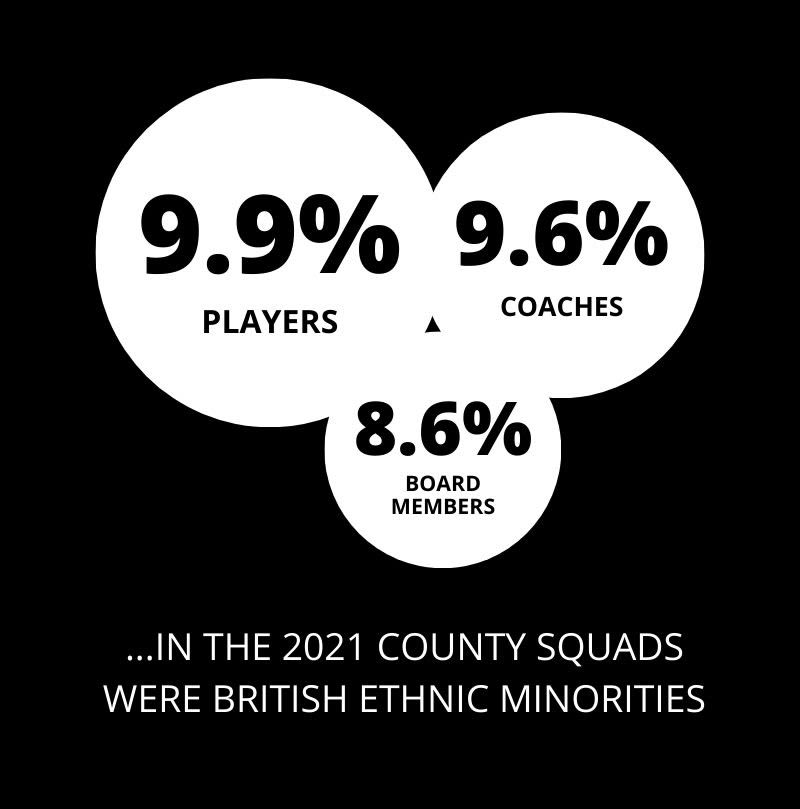

Well, when you look at professional cricket in England and Wales, what do you see? Mostly, privately educated white players.

Despite the vast number of British-Asians interested in the game at a youth level, that isn’t reciprocated at an elite level. And, for the Black community, the numbers tell the story. You can count on as many hands as you need to play the game just how many Black British professional cricketers competed in England and Wales’ premier domestic competition in 2021.

Nine.

This has to change. Why? Because cricket clubs should mirror their surrounding areas and the people within. Cricket can be a sanctuary for some, entertainment for others, and even an escape. But also, for the talented ones, a career. Every child should be able to see a path for them in the game of professional cricket, and at the moment, I’m not sure they can.

In a small office on the fourth floor at the Oval in Kennington, the ACE programme is hoping to ensure they can.

ACE stands for Afro-Caribbean Engagement. That is what the charity has set out to do. Whether it be through their schools' programmes, community hubs or identifying talent for the academy which runs all year round.

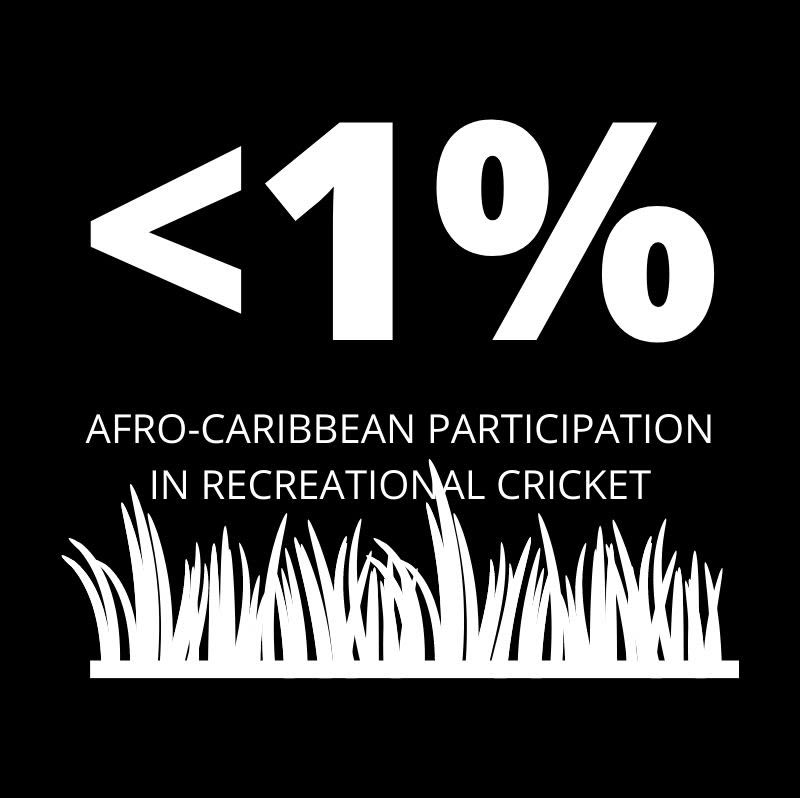

The 75% decline of Afro-Caribbean participation in the professional game over the past 25 years has led to a knock-on effect in the grassroots game. And is it really surprising? Even now, other than Chris Jordan and Jofra Archer in the men’s game and Sophia Dunkley in the women’s game, it’s difficult to think of too many prominent Black figures seen regularly on social media and TV screens across the country.

When you leave a problem untouched for some time you are inevitably going to have to deal with the lasting effects for a sustained period too. Participation among Black cricketers in the recreational game is now just below 1%. Change needs to happen and ACE are accelerating that change.

The programme was launched in January 2020 by Surrey County Cricket Club, but following a half a million-pound investment from Sport England just nine months later, the ACE Programme Charity was established aiming to ‘Support Diverse Talent from the Grassroots to the Elite’.

With the backing of many organisations and sponsors such as Sport England, ECB, Royal London and The Captain Tom Foundation, ACE has been able to set up programmes in both Bristol and Birmingham, as well as more recently, Nottingham, Manchester and Leeds and boroughs in South-East London and Essex.

MEET CHEVY GREEN, DIRECTOR

Like many of us, Chevy dreamt of being a cricketer. But when he realised that was no longer possible, a successful career in sports development beckoned. From community coach to director of programmes at ACE, Chevy has done a variety of jobs and worked with a number of programmes championing diversity.

As he leads the ACE forward, expanding into five other UK cities in the process, it’s his understanding of how to engage with parts of the community that others have evaded in the past, that stands the project in good stead.

The difference between targeting just Croydon, and not specifically North Croydon, was an example Chevy spoke of.

He said: “There are some fantastic charities that go into some of these harder to reach areas on paper, but when you break it down, were they actually going to the areas that need it (like North Croydon).

“Yes there is an element that certain kids from certain communities don’t play cricket but of course they don’t, they’ve never been provided with an opportunity to play and they’re not just going to see it randomly.

“Cricket needs to reflect the local societies that it’s in. We’re based at the Oval; Vauxhall and Stockwell have massive South American and Portuguese communities, so when we’re doing stuff in this area, that should be reflected.

“They go to all the schools we work in, so if they like cricket and show a bit of talent, of course they are going get invited to come and play. Yes football, is their bigger passion and they love Cristiano Ronaldo, but I’d love for them to say, ‘I love cricket and Jason Roy’ because they came through one of our programmes.”

Chevy is grateful for the help the charity has received to date, none more so than the backing they received from the ECB. With Azeem Rafiq’s legal case against Yorkshire CCC for institutional racism lurking over their shoulders, the ECB’s financial support will allow ACE to expand into Nottingham, Manchester, Leeds and additional London boroughs.

Chevy’s passion for the project was demonstrated in their negotiations, insistent on being able to shape the programme their way and ensuring goals are always impact-driven and not based on data.

His office at the Oval overlooks the playing square. The perfect view behind the bowler's arm. He hopes one day the impact of his programme can be so great that he’s witnessing one of his own out there in the middle.

He said: “Who knows one day I could be at the Oval behind the bowler's arm watching an ACE kid playing.

“Our short to long term goals will be making six-city academies sustainable. We’d want to have some internal competitions that are competitive and an overarching national academy squad where we’ve got the best of the best that are playing, that can challenge at the peak of our powers, more professional players, boys and girls.

“I had aspirations to play professionally, I never made it but I’ve had a successful career in sports development and one day one of the kids from the programme could be sitting where I am running the programme. To me, that’s just as successful as playing for England. We want young boys and girls having a great experience playing cricket that they feel connected to and we want to reinspire a generation.”

DYLAN LUCKY, Beddington CC

"I think my goal and a lot of my teammates’ goals are to show people that it is possible."

O'DANE GIDDINGS, Wanstead CC

"Wherever you’re from, don’t be determined who you are, you determine who you are, you are the right of your own story.”

CHEVY GREEN, ACE Director

“Cricket needs to reflect the local societies that it’s in."

"The more African-Caribbean players playing, the more people look at it and think we can do this and it will inspire the younger generation to push for their dreams instead of feeling like, ‘I’m from a certain background, I might not get in.’"

DYLAN'S STORY

Dylan Lucky is 19 and a wicket-keeper batter. He first picked up a cricket bat aged five. He attended Belleville Primary School in Wandsworth, his Dad is from Trinidad and Tobago and his first club was Purley Cricket Club. He joined ACE in 2020.

“If I wasn’t in the ACE programme I’d just be playing club cricket trying to work my way into an academy, I don’t know, I don’t know how I’d do that. In the changing rooms, we all have our own experiences and we can talk about things that we all relate to. We are all roughly the same age so we’ve got relatable things to talk about.

“We played at the Oval which was an amazing experience. It’s not exactly something that you do every day. I remember stepping onto the pitch and the grass was just so soft and you look up and see all the stands and it’s like, ‘Wow, this is amazing!’"

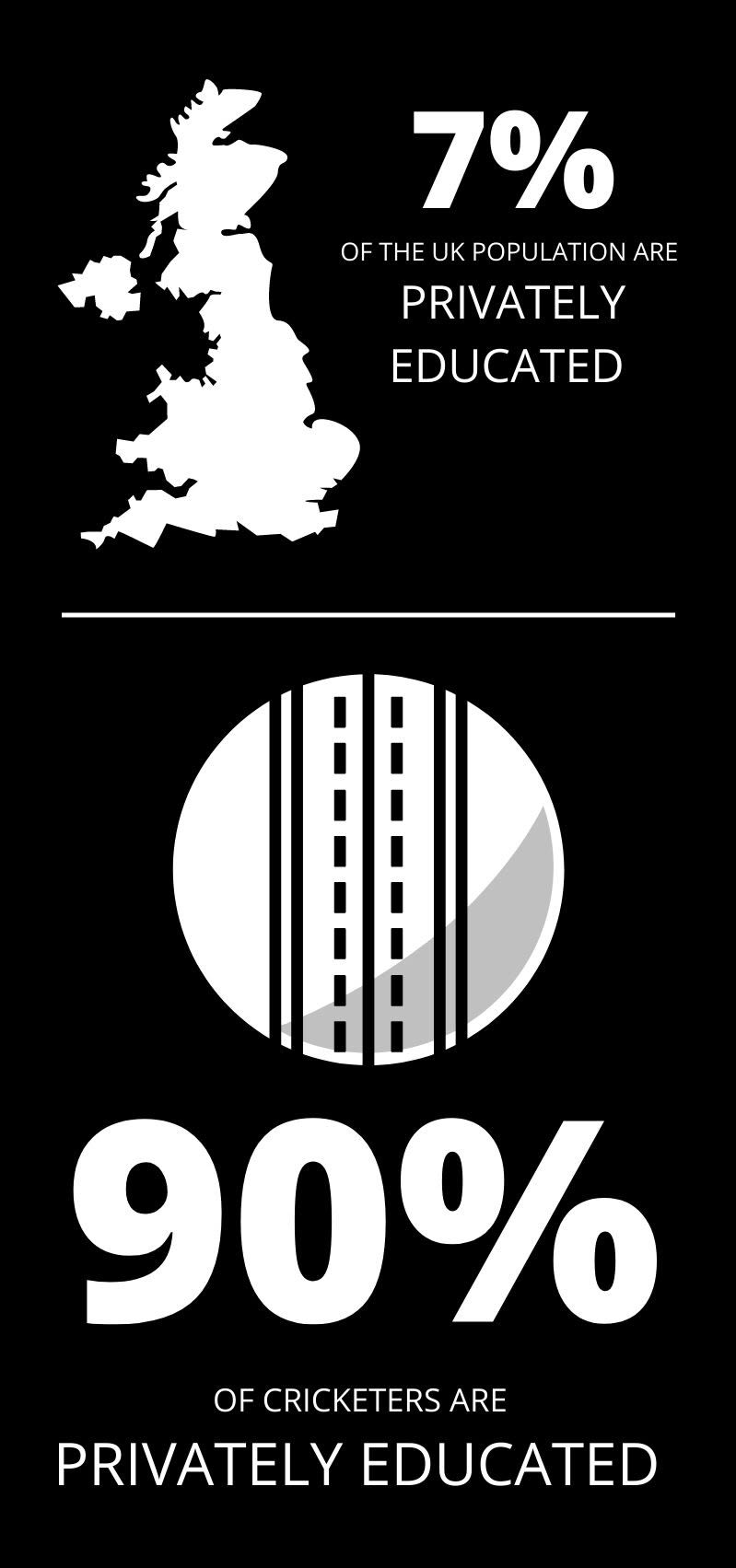

Dylan found his opportunities limited at a state school. This is a problem so many young children face up and down the country today. According to Chevy, only 7% of the UK population go to private school, yet 90% of professional cricketers in this country attended one.

Dylan revealed: “When I was at secondary school, we had a team, but no one was really interested and we didn’t play many matches. We played Sutton Grammar, Wallington Grammar and the Cedar School, who all played to a higher standard.

“My good friend, Nathan Barnwell, has just signed his rookie contract with Surrey and I feel like he’s representing a lot of African-Caribbean players. My goal and a lot of my teammates’ goals are to show people that it is possible. I remember Ebony Rainford-Brent once said, ‘you can’t be what you can’t see,’ so the more African-Caribbean players playing in the county set-ups, the more people look at it and think we can do this and it will inspire the younger generation to push for their dreams at a county instead of feeling like, ‘I’m from a certain background, I might not get in.’

“But for me personally, although barriers still need to be broken, it doesn’t exactly bother me in terms of getting into a set-up. I just feel that if I just work hard and play my game that I stick to, then I can achieve anything I want.”

O'DANE'S STORY

O’Dane Giddings is 17 and a left-handed allrounder. He played cricket with his Dad, Jamal Richards (Essex CCC) and Jamal’s Grandad in their back garden but not at state school. His first club was Bancroft Lions in Walthamstow. He also joined ACE in 2020.

“Thanks to ACE I’m with a charity called TeamArchie where I met Nick Gubbins (Middlesex CCC) who has been very helpful. We had a net session and he liked how I batted, bowled and he was going to try and get me into the Middlesex side as much as he can. I’m expecting something from them this season.”

Like Dylan, O’Dane is from an Afro-Caribbean family and is acutely aware of the systemic problems in English cricket. In the mid-1990’s there were 33 Black British professional cricketers, but in last year’s County Championship, there were only nine.

Reacting to the statistic, O’Dane said: “That is a bad thing to be going on in any sport. All sports should be loved by everyone and be diverse. For a game as big as cricket to have that many Afro-Caribbean players in a professional set-up are concerning as there are a lot of players I’ve seen who should be in county set-ups. And for them to then be doing other things, I don’t like seeing that.

“I’m not the type of person to be pushing the racist card but the way it looks, there are players who have been working their butt off, putting seven days in, 365, training training training, not going out, putting their life towards this grind to try and make it pro and they’ll be doing awesome. But, let's say there is another player who comes up, he gets a hundred, you get a hundred, but most likely they will just take the other guy, not for me to point out, but most likely because of the colour of their skin. The numbers you see are sometimes very sad. It’s like, if a white player has to make a hundred to get in the team, a black player has to make 150.”

O’Dane also never attended private school and admitted to being made to feel “different” because playing cricket was abnormal in the areas where he grew up.

He said: “I’ve had to come from certain ghettos like Tottenham being known as the guy who plays cricket. It’s Tottenham so everything is football. Whenever I tell people that I play cricket, because of where I’m from, they expect me to be doing something else. Having these types of stereotypes about me is almost kind of funny. Because even though I’m from a certain area and I’m friends with certain people, it’s like I have to be these people as well as be my own person. And it goes like that for anyone in the changing rooms that’s from ACE, whoever is listening, wherever you’re from, don’t be determined who you are. You determine who you are. You are the right of your own story.”

"I believe ACE is going to be around for a long time, I’m seeing with the players we’re starting to get, the players who are being improved and the players that are already here, I’m starting to see this as technically a county team. In terms of the standard."

THE COST OF CRICKET

Ebony Raiford-Brent, a former England World Cup winner, is the chair of the ACE programme and recently joined BBC’s Alison Mitchell on the 5 Live Cricket podcast to answer the question ‘How we can engage more people in cricket?’

TMS PODCAST:

— Test Match Special (@bbctms) May 10, 2022

How can we engage more people in cricket? @AlisonMitchell & @ejrainfordbrent present a special programme.

Guests include @tombrown1593, @abtaha_m & Ian Martin head of disability cricket @ECB_cricket.

👉https://t.co/nnojL7LD5f#bbccricket pic.twitter.com/EeLqcrXsKT

As well as being joined by ACE academy captain Troy Henry, the pair discussed the cost of cricket in the UK - another major barrier which prevents children, parents and even state schools taking up the game.

Ebony cited Matt Prior who has also been very vocal on the subject on Twitter.

I have 2 boys in the @SussexCCC pathway & it costs nearly £1000 per season per kid (coaching + specific training & playing kit they “need”). Last year they tried to charge £300 for 10 ONLINE sessions! Been appalled by this for years and it needs to change 😡 https://t.co/GSTk4nDrtY

— Matt Prior (@MattPrior13) January 19, 2022

England Men’s new Managing Director of Cricket, Rob Key also expressed his concerns when he was a pundit for Sky back in January.

And it was something Dylan felt very passionately about when I spoke to him earlier this month.

He said: “Not everyone gets to experience this level of coaching so that is an opportunity in itself to work with these coaches.

“If I wasn’t in the ACE programme I’d be paying hundreds of pounds to be with them per hour, so these kinds of opportunities that ACE are providing are just great.”

Photo credit: Acabashi; Creative Commons CC-BY-SA 4.0; Source: Wikimedia Commons

As ACE begins to expand across the country, the momentum is building. But by no means is the work done, in fact, it has only just begun. There are still major hurdles to overcome.

Chevy and the team are working with the 18 first-class counties that make up our professional domestic game to ensure the latest scholars are provided with the right opportunities to impress and stake their claim for a pro deal.

But, there are still very few Black British cricketers in the current system. There are still very few players in the current system who weren’t privately educated. Why would the scholars believe there is a path for them? Why, with few players competing week in week out whom they are able to relate to and aspire to be like, will it be any different this time around?

Chevy said: “It’s a conversation Ebony, I and a few of the coaches often have. We’re criticising the system that we feel doesn’t necessarily work or bring players through, that we’re trying to get players in! But ultimately, we want players to play at the highest level they can and hopefully play professionally. Is the structure broken? Yes to a certain degree. Are we putting players in that system? Potentially yes, but it’s how we support them and influence within. Because at the moment we don’t have a choice.”

It’s also important to remember the core values of the ACE programme and credit what has already been achieved. The keyword is ‘engagement’. Over 6,000 young people have ‘engaged’ with the programme since it launched two years ago.

The expansion across the UK will only boost these numbers too. However, as it’s already been made clear, Chevy is not concerned about the data, but more on having a lasting impact on young people’s lives.

“The kids just want to play cricket, have fun and get to the highest level. Others aren’t going to make it but it’s how we support them. We had nine kids do their level one coaching course, three of which are actively coaching on our programme. We’ve got kids in the ticket office at the Oval. One kid was interested in journalism and we got them work experience. Some of them are amazing on social media. It’s about how we keep them involved in the programme and opening their eyes to opportunities they are not aware of.

"I would love many players to play professionally but the reality is that most won’t. But, can we keep them involved in the game. Can they just love playing at their club? Become the fixture secretary, junior coordinator, or club chairperson. They might just play cricket for the rest of their lives for the love of the game and that’s just as important as getting professional players.”

All other photos from Platform Media