Across the UK, radical renters are taking the housing crisis into their own hands

In July of last year, as much of the city celebrated their home team’s triumph in the Premier League, a woman in one of Liverpool’s poorest districts was facing eviction.

At the time she was suffering from stomach cancer, and while she was still paying her rent, the property investment group which owned her house on Molyneux Road wanted her gone, so that they could convert the property into a lucrative multiple occupancy house.

The woman in question, who has always remained anonymous, was on her way to becoming one of the countless, forgotten tenants kicked out their homes every week in the UK. A few years ago that may have been how things ended.

Instead, the legal advice and physical support of dozens of local activists helped her secure an emergency ruling delaying her eviction and become another success story in the short history of ACORN, a community union bringing new vitality to the fight for housing justice in the UK.

ACORN was started in 2014 with the aim of building community power across the UK. They campaign on a diverse range of issues, but from the very beginning, when they first started knocking doors, housing was the issue that just kept coming up, and has become the issue they are most known for.

Kat Wright, one of ACORN’s national organisers, says the union’s approach is about “bringing people into direct confrontation with the people who have power over their lives.” ACORN, she says, gives a real sense of power to people who don’t feel the legal system and housing bureaucracy are set up to benefit them.

Now active in 23 cities across the country, the group in some ways resembles a traditional advocacy group: it offers advice, works as an intermediary with landlords and officials, and lobbies government at regional and national levels. It has won landlord licensing in parts Sheffield; tower block improvements and fire safety improvements in Newcastle; and protecting council tax reduction benefits in Bristol, keeping £27.4m in the pockets of working class Bristolians.

The ideal tactic is just silence and a wall of people

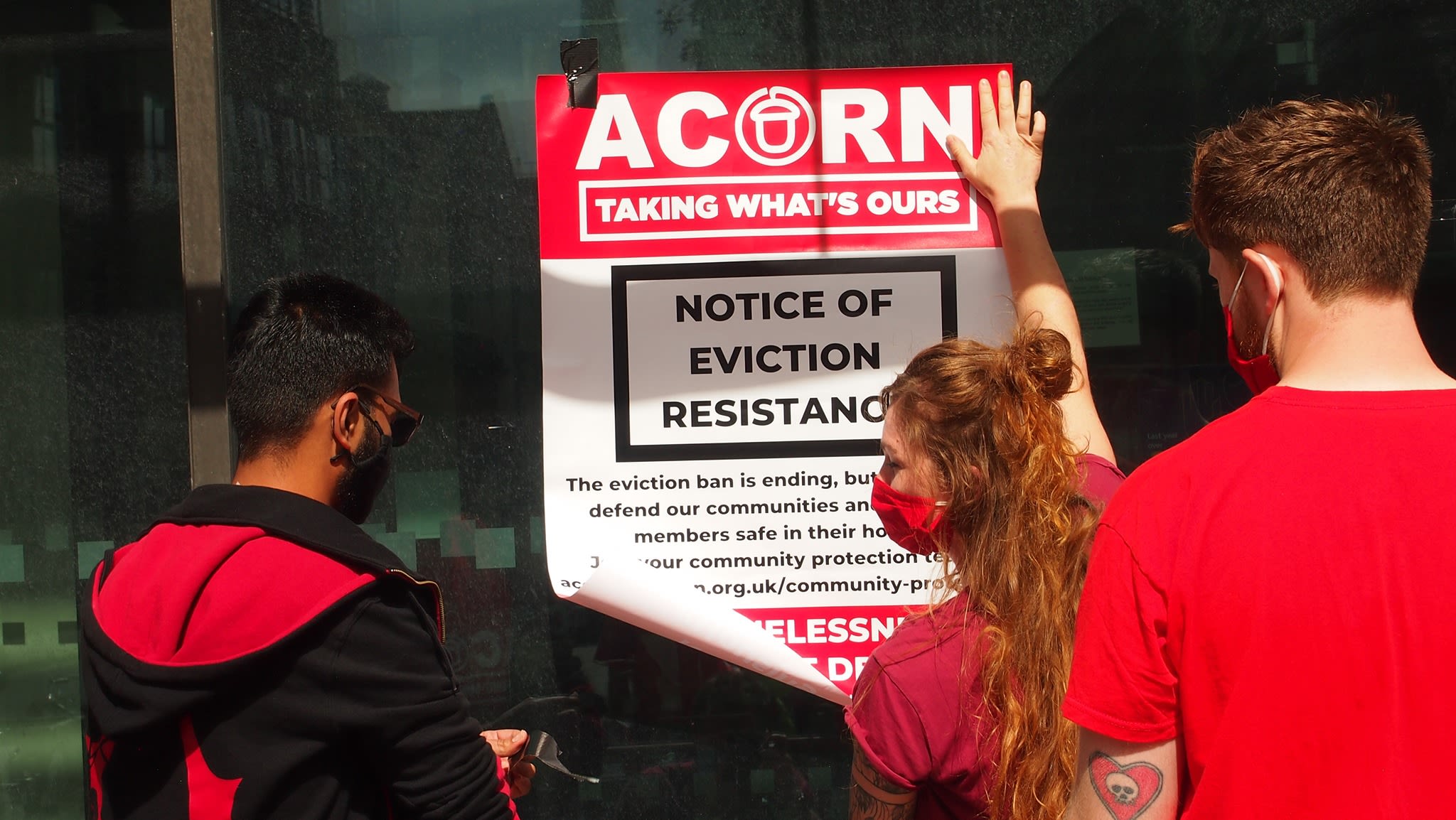

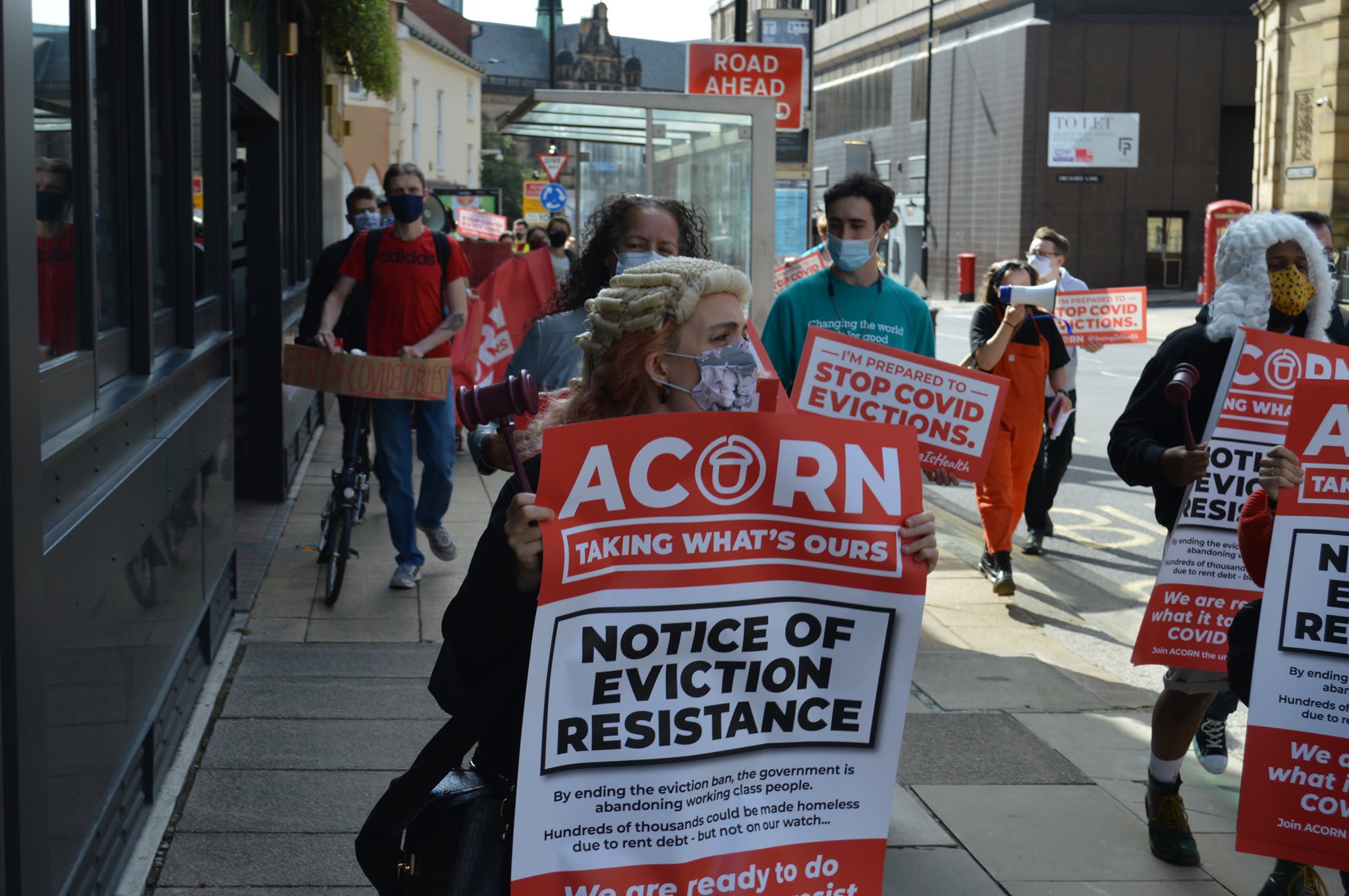

But where it has set itself apart is in its willingness to take bold and direct action against landlords when necessary and offer real, physical solidarity with its tenants. It has helped resist more than 20 section 21 evictions across the country and hold regular eviction resistance bootcamps to teach members how to protect their neighbours from illegal evictions.

The goal of these resistance training is to prevent bailiffs from entering a property by creating a protective barrier. Thomas Corrigan, who runs the union’s eviction resistance training in Liverpool, says: “The ideal tactic is just silence and a wall of people.”

Keen to ground their activism in the community itself, ACORN activists will often knock doors locally making people aware of a situation and trying to gather local support for a threatened tenant.

Where an isolated individual might be bullied into allowing bailiffs into their home, a small amount of community resistance can prove decisive. Commercial bailiffs operate on strict timetables, so disruption can be an extremely effective tactic, as these hired hands will simply move onto the next job, giving the tenant time to negotiate with their landlord.

ACORN aren’t alone in taking the housing crisis into their own hands. The London Renters Union has emerged in recent years to represent and support tenants in the capital, while groups of students across the country have autonomously – and sometimes successfully – organised rent strikes. Similar movements have also emerged in major US cities as well as in European capitals like Barcelona and Berlin.

It’s hard to say why these more direct strategies have only emerged in recent years; it may be that people just got sick of waiting for politicians to solve it.

“It’s been getting worse for thirty years now so I don’t think people had much trust in the old advocacy sort of thing,” says Thomas. “With stuff like this people can see what they are doing, they can see how they are helping.”

The union has grown hugely in 2020, with many, like Thomas, throwing themselves into the organisation after the disappointment of the general election.

“That knocked the stuffing out of left-wing people,” he says. “The whole idea of campaigning for somebody else and they’ll change it all, people got a big realisation that that’s not going to work.”

Mortgage-holders and property owners have long held huge power in British electoral politics, especially in the Conservative Party. Recent decades have seen housing tenure become one of best predictors of voting, as the country has become polarised between renters and owners.

In 2017, when Jeremy Corbyn's Labour delivered a surprising result which deprived the Conservatives of a majority, much of the party's gains were based on private renters. But it remains to be seen whether this support will be repeated. Housing activists have criticised the pandemic support offered to renters by Thangam Debbonaire, Housing Secretary in Keir Starmer's Shadow Cabinet.

Ali Avci, an ACORN organiser in Haringey, also got involved shortly after the election, helping start a group in Oxford. He was amazed by how well the group were received by the public compared with the Labour Party.

“As ACORN we were getting a really good reception on the door,” he says. “We didn’t seem like that political party that comes every four years and then disappears and doesn’t care about you.”

The organisers I spoke to were keen to point that many members were people who had not been politically engaged before, and were joining the union because they could see in concrete terms what it could achieve.

In material terms, they say, it is simply a good deal: In return for an hours wage every month, ACORN offers real, proven community power.

“It’s a minuscule fee to have this kind of element of power behind you,” he says. “where suddenly people in your local area community will stand in front of your house if they need to just to stop bailiffs from coming in.”

“It's only just begun”

The pandemic has been a contradictory experience for the union. While it has frustrated their combative in-person approach, it has also seen their membership swell to more than 5,000.

“Obviously we’ve had direct action which usually means we’d go to a place and either protest or leaflet, it’s very physical, out in the open, you know, face-to-face contact with people,” says Thomas. “With the lockdown that’s obviously the one thing we’re not allowed to do.”

ACORN’s answer has been rolling pickets, with activists ‘relaying’ in and out of protests to pile pressure on dodgy landlords while allowing social distancing.

Other socially-distanced tactics include communications blockades, in which activists jam the phone lines of lettings agents; leaving placards at the door of a landlord’s office one at a time until an avalanche of signs has built up; and booking fake appointments to view flats and houses.

Britain’s tenants have been frozen in a strange and precarious state. The industries most badly effected by the pandemic have a large number of renters, and while evictions are still prohibited, there has been little financial support for tenants, with many dangerously in debt. Homelessness charity Shelter estimates that 332,000 private renters who were not in arrears before the pandemic are now behind on their rent.

“We are preparing and expecting whenever the eviction ban officially does end there will be a massive wave of evictions,” says Ali.

We're gonna be huge. It's only just begun

One potential tactic could be rent strikes, where groups of tenants collectively refuse to pay rent in order to win concessions from landlords or public authorities. It’s a radical tactic, and one with potentially damaging legal ramifications, and while the activists I spoke did not condemn it, they were keen to emphasise the importance of protecting members and building power.

Thomas says that while ACORN activists have advised people planning rent strikes, “at the moment we don’t feel we’re fully capable of organising [one] by ourselves.”

Whatever their strategy going forward, the union seems keen to get there quickly. “We don’t have the time to start the amount of towns and cities that want to start ACORN branches now,” says Kat, who insists that ACORN will one day have a branch in every UK community.

“We’re gonna be huge,” she says, “it’s only just begun.”