ADHD in the Criminal Justice System

Screening in police custody and beyond

By Kristina Wemyss

The City of London Police became the first force in the UK to screen detainees in custody for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) last month.

The pilot, which will last for three months and continue if successful, allows those in custody to get fast tracked ADHD diagnoses if it is believed this would impact their case.

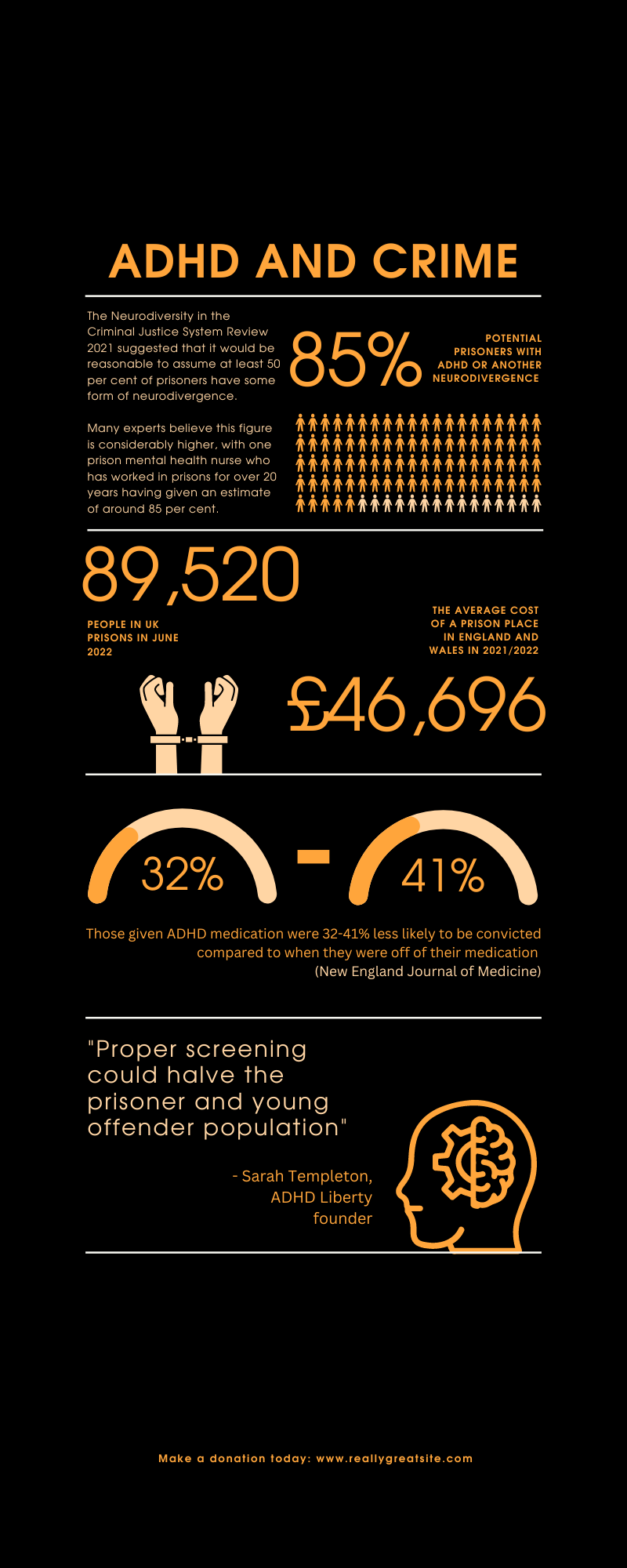

The Neurodiversity in the Criminal Justice System report 2021 suggested that it would be reasonable to assume that at least 50 per cent of prisoners have some form of neurodivergence.

Many experts believe this figure is considerably higher, with one prison mental health nurse having given an estimate of around 85 per cent.

The aim of the pilot is to identify those with ADHD entering the criminal justice system so they can receive fast-track NHS diagnoses within one to two weeks.

It is hoped this will prevent reoffending and give a better understanding of the link between ADHD and crime.

An 18-question form will be given to every individual when booking in. This is not an assessment for ADHD, but an initial indicator as to whether an assessment should be given.

Then, an assessment will be made on whether a diagnosis could have a significant impact on the case, with factors including the severity of the crime and repeat offending being taken into account.

The pilot has been devised by counsellor Sarah Templeton, who has worked in four prisons, alongside Daley Jones, a MET Detective. Both of whom are ADHD diagnosed and work to support those with ADHD in the criminal justice system and the police.

The current pilot itself is being run cost-free (aside from the printing of the forms). The pilot's creators hope screening will be rolled out to other police forces and prisons across the UK.

Questions have been raised ranging from whether offenders could abuse this system, to whether fast-tracking those in custody unfairly increases the NHS wait-list for other individuals.

I spoke with the people behind the pilot to find out more.

Confusion over how to define ADHD has increased in recent weeks. Particularly in the wake of the BBC's much-discussed Panorama documentary, which brought the legitimacy of diagnoses being given by certain clinics into question. Some people have gone so far as to question whether ADHD exists at all.

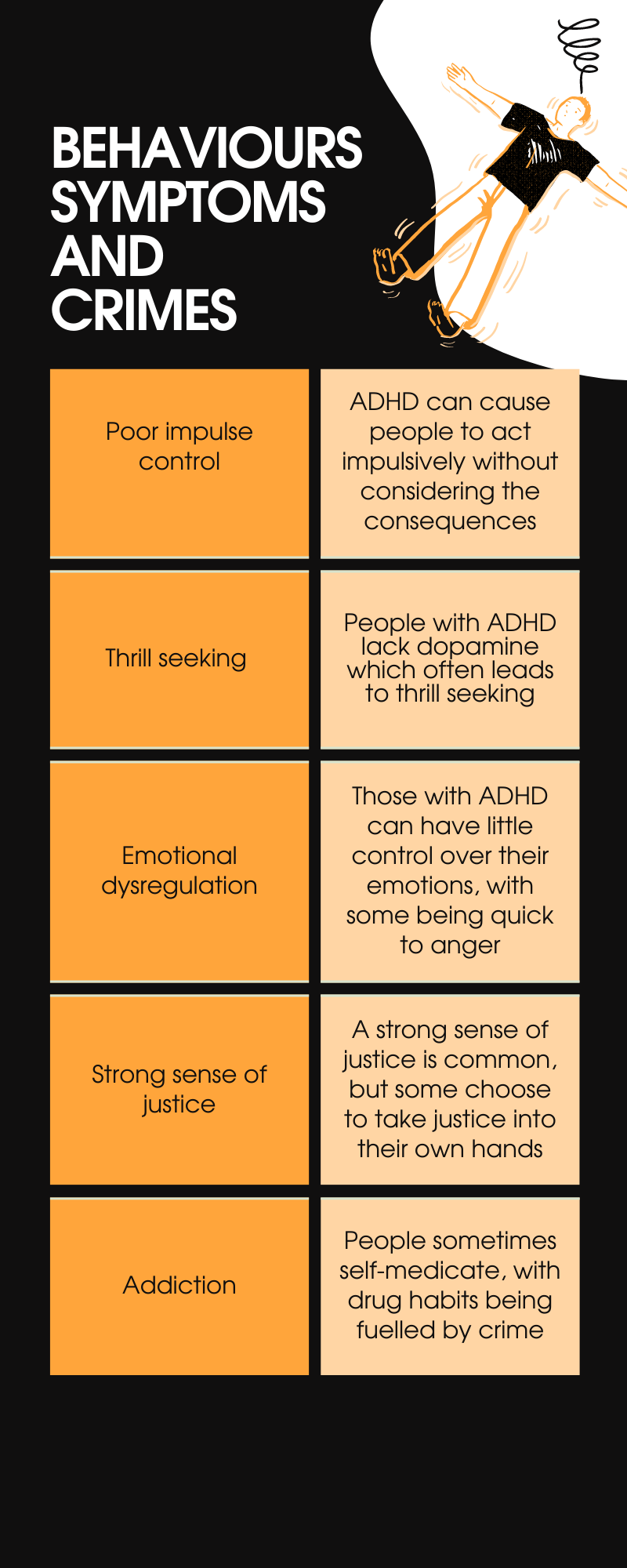

ADHD presents in a variety of ways, through hyperactive, impulsive, and inattentive tendencies. People can fall into one of these categories or present a combination type.

Many of the tendencies associated with ADHD can make a person more likely to become involved in the criminal justice system, as explained on the right.

Sarah and Daley, who developed the screening system being implemented by the City of London Police, have worked with people with ADHD inside and outside prisons.

From their experience, they believe screening is a simple tool that will help protect the public, save money within the prison system, and keep those with ADHD safe.

One ex-offender who Sarah Templeton worked with for ten years spoke to me about his experiences. From his teenage years, he was a prolific offender and spent time in a handful of different prisons.

In a conversation with Sarah, the possibility of ADHD was raised. He received a psychiatrist assessment and was prescribed medication to manage his symptoms.

He told me: "100% of my crimes were linked to my ADHD.

"A lot was connected to alcohol, which I used to self-medicate.

"This resulted in me getting into fights, stealing, causing affray, and criminal damage."

While growing up, he said he never felt that he fitted in, struggled with anger and boredom, and resented school.

Working with Sarah changed his life. Since being medicated, he has not reoffended for two years.

Things are different now, he told me. He has a successful job as a scaffolder, and he now has a family with a young child.

He said: "I can focus now, concentrate, I'm calmer and I rarely drink."

If it were not for his diagnosis, he believes life would have been very different: "I would be in prison. Again. Or dead from alcoholism."

Sarah Templeton Counsellor and ADHD Liberty founder

“Prison’s would half empty if you would screen, diagnose and medicate those with ADHD.”

Sarah has worked as a counsellor in four prisons and with ex-offenders on the outside for 30 years, she was also diagnosed with ADHD in 2015. From these experiences, she noticed a strong link between offending and ADHD.

Her work has gained the support of Met Detective Daley Jones, who created the pilot screening with her. Ex Minister for Justice Sir Robert Buckland has also expressed support for their scheme, and confirmed he would like to see screening throughout the whole criminal justice system.

At her first talk with Daley’s police support group, over 400 people attended, and she said she has seen much support from the force.

However, there is still a lot of stigma around ADHD: “It’s dreadful, and I think one of the reasons people don’t believe in it is because everyone with it is so different, there’s no visual marker, we aren’t all walking around with the exact same symptoms, so people can’t group us together.”

Sarah suggested it might be easier for people to understand if the term ADD was brought back to identify those who have the attention deficit (or inattentive) symptoms, but lack the hyperactivity associated with the umbrella term ADHD.

Some people have asked whether people might abuse the system to get a quick diagnosis by committing a crime, by-passing the current NHS waiting lists of two to five years in some areas.

This cannot be ruled out as a possibility, however, Sarah said the types of vulnerable people who tend to come through the criminal justice system deserve to be given priority.

“The government would save fortunes if they screened people properly. Rather than ploughing money into huge new prisons to lock more people up, they should be assessing the people already in prison and those coming in, ensuring they are properly medicated, and safely releasing the vast majority of them back into society.”

"This would reduce crime rates which would keep the public safe, help the wellbeing of people with ADHD, and save the government huge amounts of money.”

At the four prisons where she has worked, Sarah said there was no screening in place: “The majority of staff in prisons still think ADHD is a childhood behavioural disorder that you grow out of in your late teens.”

She also said ADHD is regularly misdiagnosed in prisons: “Personality disorder diagnoses are handed out like sweeties, because you don’t medicate them, so they don’t cost the prison service anything.”

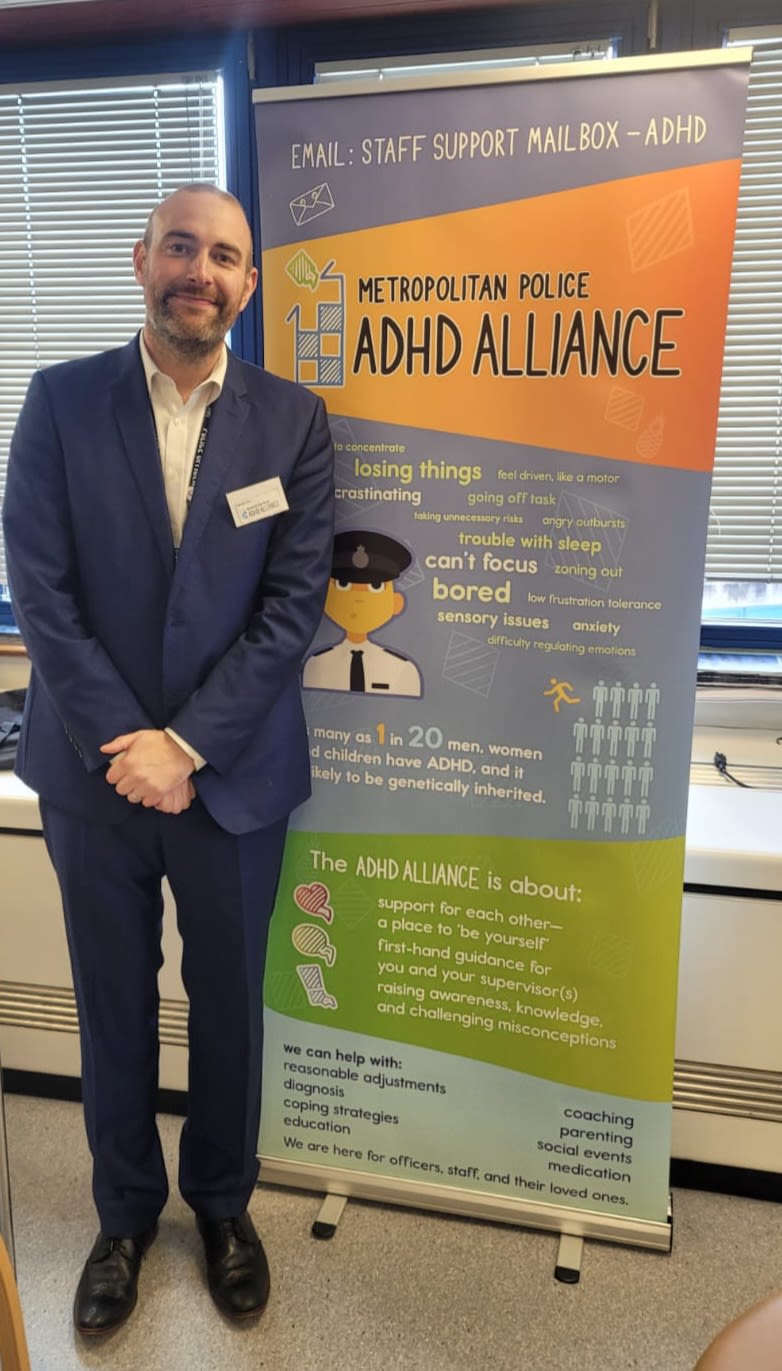

Daley Jones MET Detective and ADHD Alliance co-founder

"The MET is receptive to change, but I really hope those changes start to happen more quickly."

Detective Constable Daley Jones joined the police in 2007, and was diagnosed with ADHD in 2021. He has worked across a variety of teams but now primarily deals with safeguarding.

After his diagnosis, Daley looked for help and guidance within the Met. However, he found there was no support group for ADHD like there was for autism.

He decided to set up a group himself, which now has more than 500 members. This number is perhaps so high because people with ADHD tendencies are attracted to fast-paced, impactful, and thrilling work, which can be found in the police.

Although Daley spent little time in uniformed work on the beat, he rarely got into situations involving a “roll-around”. He put some of this down to identifying with those who had ADHD tendencies and his ability to de-escalate situations.

The screening system is being piloted with the City of London Police partly because the force is relatively small. Daley explained: “For me to speak to anyone who has the power to change things, it’s difficult in the MET.”

The MET (and police more broadly) are receptive to change, Daley said, but he believes these changes need to be made more urgently.

“They know they need to introduce neurodiversity awareness training to their staff and I do think it’s on the cards.

“I genuinely believe everything we are doing in terms of training and screening will happen, but I hope it happens quickly, because society really will see a benefit.”

Screening is going to be rolled out across several police forces in the UK, with Cumbria police and Thames Valley police among those who have expressed an interest. Sarah estimated around 13 or 14 forces had been in touch with her to ask about the forms.

She also hopes to see screening implemented across prisons, and importantly, youth offender institutions - to prevent young people from becoming prolific offenders.

Beyond custody, the ADHD Act put forward by Sarah includes a big emphasis on identifying those with ADHD earlier in schools and providing them with support.

This Act is currently being worked on by a team of neuro consultants, headteachers, prison staff and police who are trying to get it through the government.

To parents of those with ADHD traits, Sarah gave the following advice: “Sign them up to every sports club, drama club, singing group. Get that adrenaline in the right way so they don’t end up going out and stealing a bike to get it.

"These ADHD traits aren’t going anywhere but if you focus them in the right direction you will keep the young people out of the young offender courts.”

Image credits:

Police station: Unsplash via Maggie Yap

Silhouette behind bars: Unsplash via Mikhail Pasynkov

City of London Police: Unsplash via James Eades

Sarah Templeton: Sarah Templeton

Daley Jones: Daley Jones

Final background: Unsplash via Adrien Olichon