Are literary festivals prepared for the future?

How book events are managing during the cost of living crisis

Literary festivals have been a bedrock of the cultural landscape for decades. A place where lovers of words meet authors, ask questions and engage in intellectual discussion, festivals of all shapes and sizes have sprung up around the country.

Like all live events, the challenges confronting literary festivals are stark. Forced to move online during the Covid-19 pandemic, ticket sales were lost as teams adapted to virtual technology. Though events are now in-person, the cost of living crisis raises questions over whether individuals want to spend their smaller disposable income on cultural events.

More broadly, festival inclusivity and accessibility is a big issue. Festivals have tried to combat accusations of being too exclusionary and middle class with programmes lacking diversity. Festivals have also faced criticism for not financially compensating their guests, further narrowing who is able to speak. This raises questions over whether literary festivals are reaching their full potential audience. Put simply, do literary festivals have a bright future?

The picture is greatly varied, but, initially, not overly optimistic. In November 2022, Edinburgh International Book Festival announced it would be scaling down due to “the unpredictable nature of the external environment.”

Their own evidence suggested audiences were attending fewer events and spending less money. Given the cost of managing literary festivals, the timing could not have been worse. The festival's delivery would be smaller, as staff numbers were reduced.

Edinburgh is widely regarded as one of the big three literary festivals, along with Cheltenham and Hay. Founded in 1983, it has been held annually since 1997 and is a crucial part of Edinburgh’s transformation into a cultural and political hub every August. If a festival of its scale is financially insecure, what hope does this offer lesser well known gatherings?

Lee Randall is a freelance Book Festival Programmer based in Scotland. In 2020, she wrote a report for Creative Scotland examining how Scottish literary festivals adapted to the pandemic to ensure their long term viability.

She first became engaged in literary festivals as an arts and features journalist, allowing her to chair events and write book reviews.

Randall believed literary festivals having no fixed size was one of their strengths.

“You can do it very small scale. You don’t need music, you can do a literary festival on a budget.

“And you bring something, you’re bringing a little circus to town.

“Or you can do a massive, giant, all bells and whistles literary festival that costs millions of pounds to produce and bring a different kind of show to town,” she said.

Given Randall's report specifically referred to Scottish literary festivals, she stressed the number of literary festivals within Scotland.

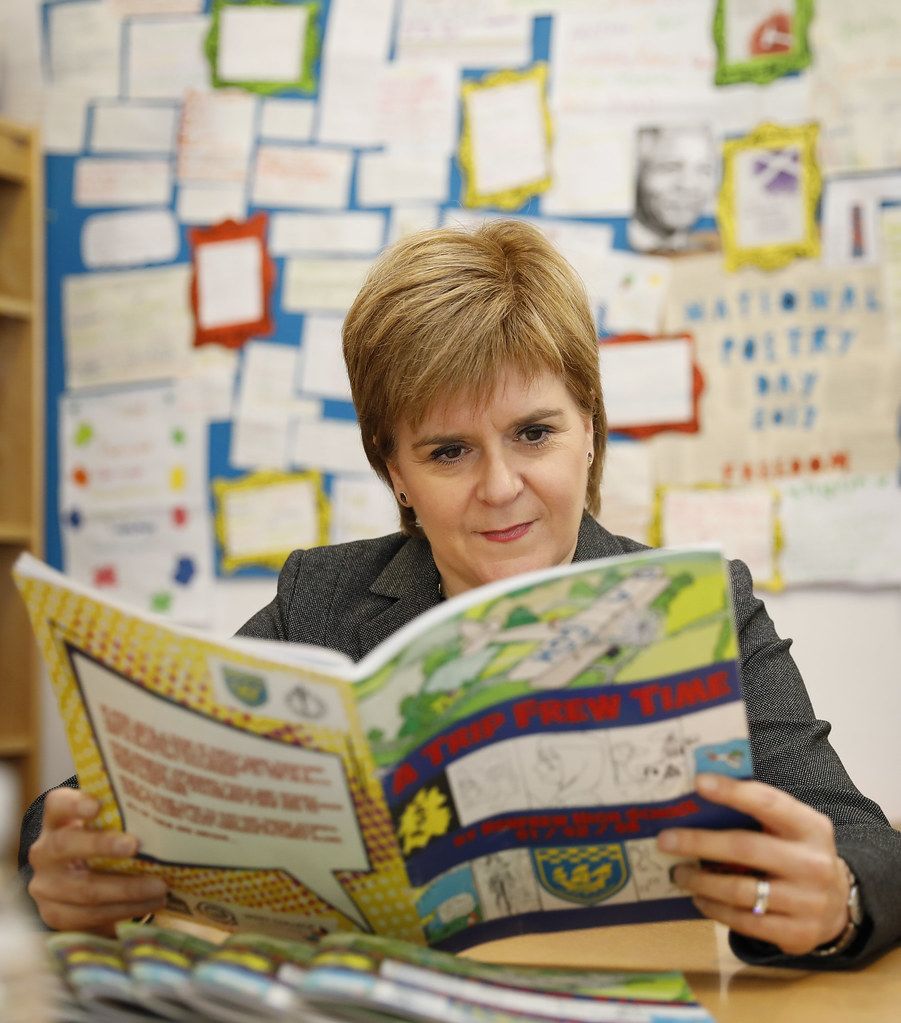

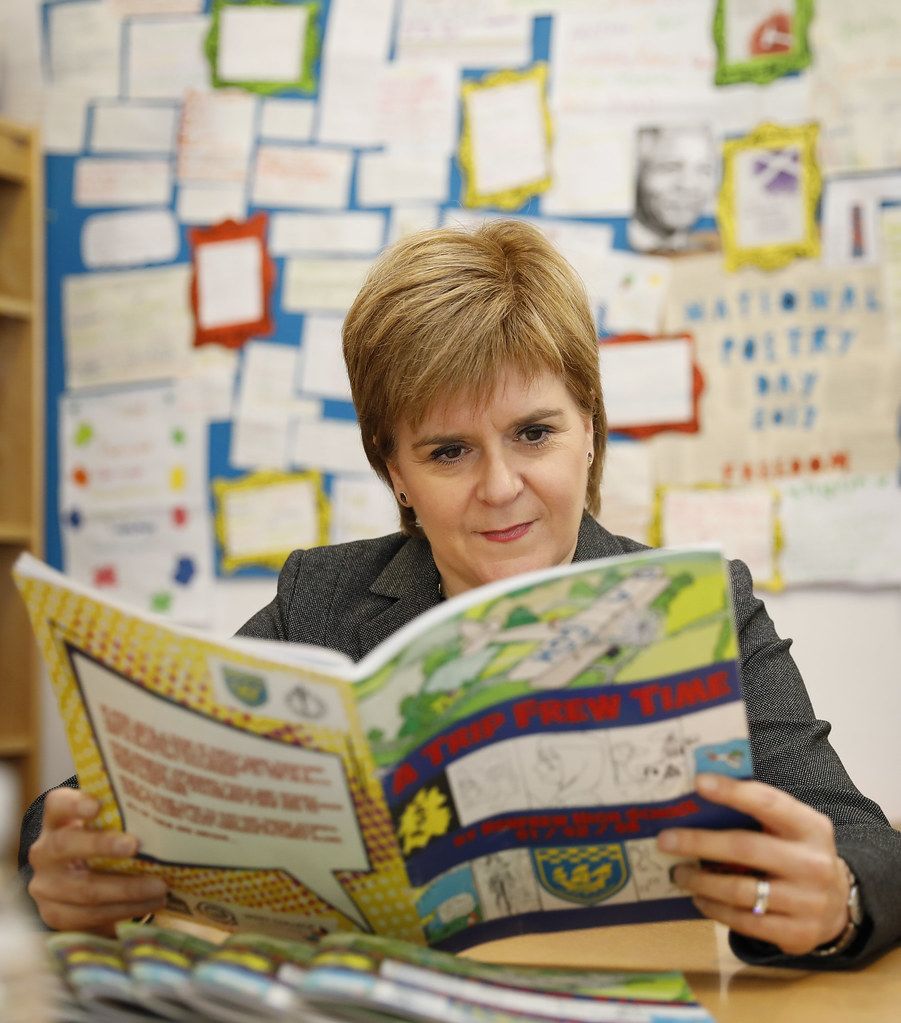

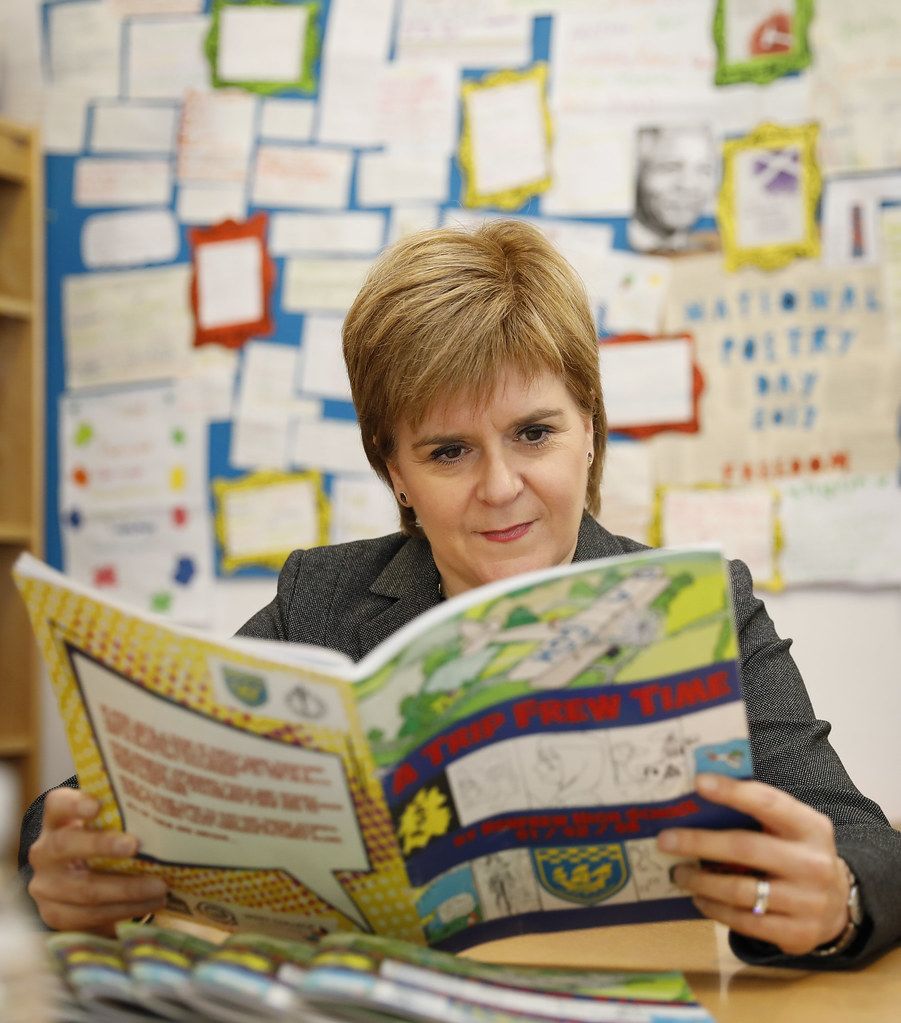

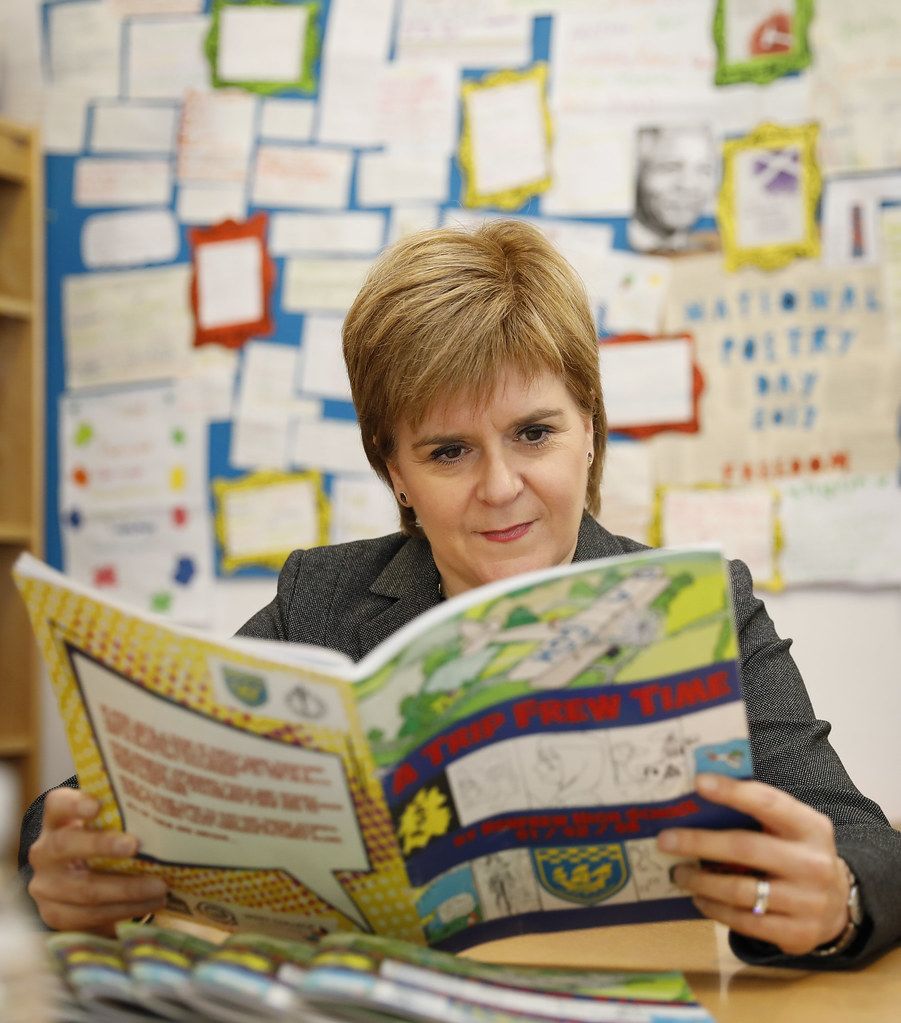

“Our current First Minister has reading programmes and is herself a very outspoken fan of reading so books are very much to the forefront of the public imagination,” Randall added.

However, Randall questioned literary festival inclusivity: “I think if you go to many book festivals, not all, the audience tends to be older, they tend to be middle class to upper middle class, people with disposable income and free time.”

She stressed literary festivals needed to challenge this stereotype and ensure those who did not read particularly often felt included.

Randall was positive literary festivals could improve their accessibility through ticket sales, while also admiring the speed at which festivals moved online.

She said: “I think that most festivals were remarkably a joy and managed to pivot to digital really quickly.”

The importance of grants was apparent. Edinburgh International Book Festival receives money from Creative Scotland, while many English literary festivals depend on Arts Council England.

Given the cost of festivals, Randall believed in multifaceted funding streams.

“Getting funding is a tricky thing. I think corporate and individual and other kinds of sponsorship are equally necessary plus ticket and book sales,” said Randall.

Literary festivals depended on attendees visiting. Did Randall worry about declining disposable income nudging people away?

“I think that for those people who already didn’t think book festivals were for them, they’ve got limited income, I suspect that they're going to be the hardest hit regardless.

“I don’t blame anyone who says I’d rather buy a coat than a book.

“I totally get that, I respect that; I think it’s a tragedy,” she said.

Randall felt the future of literary festivals would come from older generations bringing their children and grandchildren along, partially achieved through technology.

“There are authors who are saying ‘well, why fly around the world, burning up fossil fuels, when I can do this from home?’" she said.

“Now, there are huge disadvantages from everyone’s standpoint but there are also advantages.”

What are literary festivals like? Wigtown Book Festival is based in south Scotland and has taken place since 1999. Anne Barclay is the Operational Director for Wigtown Festival Company, the organisation behind the festival, which has evolved significantly since its founding.

Wigtown Book Festival developed as Wigtown became Scotland’s national book town. The title was won after a University of Strathclyde competition to find the Scottish equivalent to Hay-on-Wye. Barclay said the first festival contained just a few events over one weekend. By contrast, the festival now has more than 300 events over ten days, bringing almost 30,000 visitors to Wigtown.

Barclay recognised the value of literary festivals: “Their importance really in the cultural landscape is vital to allow people to come together to promote good discussion and debate and grow knowledge.”

Every successful book festival must be unique. Barclay stated Wigtown Book Festival did well because it was not just a book festival.

“So our town square has more than a dozen bookshops and book-related businesses that visitors can get lost in,” Barclay said.

Barclay said the programming team base decisions off loose themes, with 2022’s theme being the ‘Year of Stories’. The remote location means authors should have something to promote, with often a day’s travel spent getting to the festival.

Barclay added: “It’s really vital to have a good relationship with the publishing houses to know what’s coming up and what the opportunities for programming are in the year ahead.

“But also from our perspective, probably quite specifically and uniquely, is our location, so it’s important for us to be able to communicate with the publishers about how well we promise to look after speakers while here because we are asking them to come a long way.”

The inclusivity of Wigtown Book Festival was important to Barclay, as the festival prided itself on accessibility. The lowest priced ticket was £5, with the majority of tickets costing £7.50. By contrast, previous festival prices ranged from £7 to £12.

Barclay said a ‘pay what you can’ scheme was introduced, where there was an option not to pay if this proved unaffordable. Free tickets had always been on offer to young people, carers and the unemployed.

Barclay believed the festival successfully adapted to the pandemic and retained its audience.

“We started a series of events called Wigtown Wednesdays which were weekly events held online to engage our audience and those were really incredibly successful,” she said.

Despite the cost of living crisis, Barclay remained optimistic about cultural engagement. However, she noted Wigtown’s ticket sales were 60% of their 2019 rate. This meant, while the audience return rate was greater, visitors were buying less and staying for less time. With the cost of travelling to literary festivals, attending can be a challenge.

“I think there are lots of factors at play for how difficult it’s going to be in the future to get the audience to engage in book festivals,” Barclay said.

Despite new technological developments, Barclay believed Wigtown’s unique status would remain core.

She added: “Because we’re in Scotland’s national book town, the written word on the page will always be core to what we do and will be one of our priorities to maintain.”

The media coverage literary festivals receive impacts the public’s perception and interest. Journalists are therefore key. Alex Clark is a journalist who has chaired festival events and been a guest director at Cambridge Literary Festival.

Clark noticed literary festivals proliferate as Hay and Cheltenham's monopoly reduced. The reason for their expansion was less clear.

“It was just a sort of cultural moment that obviously lots of people capitalised on.

"I think as much as anything, it was just to do with realising that there was a kind of appetite for readers to connect with writers and that they were keen to be able to go to something that was an extra step in their reading experience,” she said.

Clark thought culture journalism played a big part: “The role of features in newspapers became more important, bigger in the mix.

“That led to an understanding of the industry as something that needed to have a more personal element.”

Literary festivals, Clark believed, had to include both bigger names that would pack out the crowds and newer writers visitors may never have heard of.

“For the attendees, what you want them to feel is they may discover somebody that they haven’t heard of before," Clark said.

“You hope they’re going to get something extra as well as going to see a favourite writer or a performer."

Given Clark’s experience in literary festivals, she reiterated the importance of a good working relationship between any publisher and festival. Given a publisher often manages the publicity tour for a new book, both festivals and publishers had an interest in promoting the work.

“If you ran a festival with very small events of quite niche authors, or writers that just don’t have a particularly high profile, it wouldn’t be financially sustainable," she said.

“If you ran a festival that was all the sort of tent fillers, you wouldn’t be doing very much for the literary ecology.”

When programming, Clark spoke about a festival’s audience. In particular, she said sometimes festivals were not the most ethnically diverse, with women more likely to attend.

Clark was positive about how festivals balanced pricing and accessibility. Nonetheless, relying on ticket sales alone was not an option.

“I do think it’s really tough and I think funding streams are very difficult for festivals," she said.

“It does largely come down to sponsorship and public funding."

The logistical costs of festival management were apparent. From renting venues to energy prices, the work behind the scenes was significant.

Despite online events improving accessibility for those unable to attend physical events, Clark was concerned about impacts on ticket sales for festivals.

“We definitely noticed, just after Covid, the first festivals and live events, there was a hit in ticket sales, because people were still, for lots of reasons, nervous, especially perhaps if you have an older demographic, about being in public spaces with a lot of other people," Clark said.

“You were delighted to be back and you were then faced - this is a story I heard over and over again across the board - with really diminished audiences.”

With audiences now returning, the greater cost can be transport, rather than the events. Clark believed literary discussions were at their best when they favoured conversation.

“In terms of the conversation and the debate, I think that will endure because I think we’ve also become very aware of how atomised parts of society have become, how locked in echo chambers people have become, how difficult people find it to have a conversation or discourse via social media," she noted.

“The good thing about festivals is just the moment of listening to the author speak about their work or read from their work that is completely galvanising and electrifying.

“But you can’t just get it by something pre-prepared or premeditated, it’s the fact that you’re hoping for the unmediated moment, the live moment and I hope that will continue.”

So what is the festival where Clark has been a guest director like? Cambridge has had its own literary festival for nearly 20 years. Marina Scott is an assistant programmer who works to support festival director Cathy Moore in delivering a twice yearly programme.

The festival was first known as Cambridge Wordfest back in 2003, delivering two annual festivals from 2008 and becoming a registered charity as the Cambridge Literary Festival in 2014.

Scott argued literary festivals serve multiple purposes. She said: “I think writing can be quite a solitary thing so it’s really lovely to get authors to come and talk about their books.

“Education is at our core - we think it’s really important to debate and hear conflicting opinions.

“Our tagline is broadly ‘for the love of books’ so we love what books allow us to experience and the ideas.”

The picturesque landscape of Cambridge, Scott commented, also gave the festival a unique atmosphere.

Themes for the festival were decided as the team ensured they reach a wide audience, being unafraid to cover political topics.

“We have lots of communication with publicists and pitch meetings," Scott said.

“We tend to pick out some themes quite early on when programming, which tend to reflect things that are happening in the world, the mood of the population.”

The Cambridge Literary Festival has been affected by the cost of living crisis. Scott said they try to keep in mind economically disadvantaged individuals through concessions.

Scott stated the impact of Covid-19 on the cultural scene had been wide ranging, both positively and negatively. The Cambridge Literary Festival’s spring edition was due to occur a month after the first lockdown.

She said: “The whole cultural scene in the UK is still kind of reeling from the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic and some institutions are just getting back on their feet.

“We were lucky in that we had an archive of digital material that was just waiting at our fingertips to be turned into consumable content for our audience.

“We also, in a really quick turnaround, put together a collection of video interviews, podcasts and online content for our audience members which we released and it was free for anyone to access called The Listening Festival.”

Three online festivals were ran, with freelance digital producers helping create content. Even as Covid-19 restrictions ended, the festival retained recording live events for individuals unable to attend.

Scott remarked it was important to remember, while free culture exists, its perceived elitism must be countered.

She said: “I don’t want to assume that people cannot access culture in a way where they don’t have to spend money because that’s not true.

“I think what you’re getting at is the fact that cultural institutions can be perceived as elitist and I think that’s something we work really hard at the festival to try and counter.”

Polling conducted by YouGov in 2020 | Image credit: Graph made on Flourish by Noah Keate

The success of any literary festival is dependent on people reading books regularly and talking about them. YouGov data from March 2020 on UK reading habits is concerning. 18% of people said they never read for pleasure, with another 18% reading less often than once every six months. Strikingly, less than a fifth of respondents said they read every day.

Polling conducted by YouGov in 2020 | Image credit: Graph made on Flourish by Noah Keate

The picture is more positive for traditional reading. In the research, 60% of adults said they preferred physical paperback books, while less than a quarter favoured e-books. Though the death of the novel has long been predicted, Kindles have not overtaken printed books for a preferred reading style. When the financial situation of publishers and authors can be so precarious, that is reason to celebrate.

The attitude magazines take towards book festivals can shape reader opinions. Sam Leith is literary editor of The Spectator and noted their “explosion” over the last decade.

He said: “Because of digital technology, so much is available in such a solitary way and at any time.

“There came this hunger suddenly, a return to an interest in live performance and the idea of experiencing something communally.”

Leith detailed how festivals were a great benefit to authors, given they spend most of their year writing alone, and were vital in the publishing ecosystem.

“I think almost every publisher does put their authors up for literary festivals and sort of slightly twist their arm to do them.

“I think it’s a mixture of being fun for authors and fun for publishers, it’s good networking.

“Publishers wouldn’t send their authors to do it if it wasn’t a means of increasing sales.”

Despite their impact, Leith’s editorial decisions at The Spectator are not framed by literary festivals.

“If something interesting happens at a literary festival, I might write about it but the pages I run at The Spectator are entirely led by the publication of books."

Leith argues it is not obligatory for literary festivals to address stereotypes of attendees, arguing it is framed by the festival.

“It doesn’t seem a problem to me if people who happen to like attending literary festivals go to literary festivals," he said.

“I think literary festivals just put the books out there.

“They programme them according to their audience.”

He believed the variety of festivals, whether catering for traditional history or slam poetry, meant more people would attend.

“There will be festivals that I think cover all sorts of the demographics of people who read books,” he said.

Leith reflected on how Covid-19 restrictions invariably diminished the experience of literary festivals and cultural engagement.

He added: “Either, you’re sitting with your computer screen absolutely tiled with hundreds of audience members sniffing and picking their nose and playing World of Warcraft or you’ve got simply you and the person you’re interviewing.

“And it has all that difficult grammar of Zoom meetings without the sort of warmth and spontaneity you get from being in a room with an audience where you can hear them clap or laugh or express interest.”

Leith felt optimistic about the future of literary festivals, thanks to their volume.

“Most literary festivals, because there are so many of them, lots of them are local to people so you’re not travelling miles and doing all the things that really start to push the costs up,” Leith added.

He argued the average cost of a literary festival ticket was not much more than a paperback book. Instead, the costs were in accommodation, particularly for remote festivals, though this would not end them altogether.

“Particularly if, and there’s probably some truth in it, the bread and butter audience for most mainstream literary festivals is at least relatively prosperous,” Leith said.

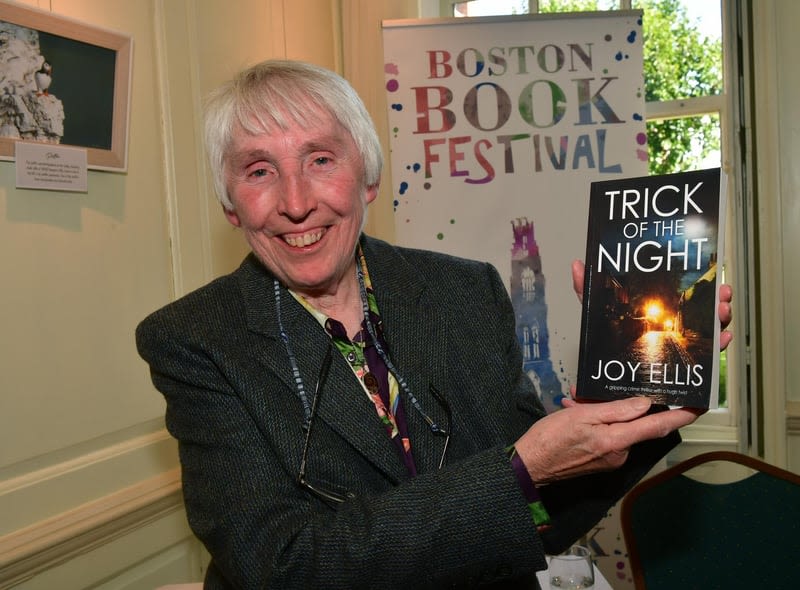

The cost of living crisis impacted festivals in their infancy. Last year, Boston Book Festival, in Lincolnshire, took place for the first time, with its second festival in September 2022. Sue Morrison, a retired headteacher and festival secretary, said the festival’s origins came from wanting a nice local festival.

She felt inspired to co-found the festival to turn Boston’s reputation around.

“It’s a small town with an awful lot of history and it’s also a small town with a really, really bad press.

“We seem to get all the very negative things in the newspapers.

“On television we were once known as the murder capital of England and the fat capital of England.”

Morrison’s passion for Boston was crucial, with an inspiration to promote local authors by dealing with them directly.

“It’s a lot easier if we deal directly with authors, rather than through the publisher or through the agent because you build up that rapport,” she said.

Morrison said the festival caters to a variety of genres and audiences, though Lincolnshire has numerous crime writers.

Boston Book Festival aimed to keep its pricing affordable by charging £7 for events. One day is a drop-in, where people can see authors for free. Unfortunately, their budget is limited.

The festival started in the aftermath of Covid-19 restrictions ending, taking place this year the weekend before the Queen’s funeral.

As a new festival, working with local venues has proven essential.

“We’ve been in very close contact with our local theatre.

“It’s one of our venues; they support us really well.

“They are having to cancel events.

“It’s been unheard of but they’re just not getting the support,” she added.

Morrison said they will cut back the festival next year, prioritizing one author at a time rather than multiple events at once.

Morrison hopes technology won’t radically change literary festivals.

“Authors will give you their life story and they are just like us.

“They are ordinary people and for children that is so inspiring.”

Literary festivals cannot ignore their star attractions: authors. The success of literary festivals depends so much on its guests. One prolific author who has seen their evolution is Louise Doughty. Author of nine novels, including Apple Tree Yard (2013), Doughty’s knowledge of literary festivals is vast.

Her first memories were going as an audience attendee before being a published author.

“I would go and watch published writers and I just thought they were Gods, because they were everything I wanted to be," she said.

“They’re one of the few places left where people are really discussing complex ideas at length,” Doughty added.

Doughty believed their growth came from book groups embracing grassroots engagement. She felt this held more importance than newspaper book reviews.

“I mean, the books pages are important and they’re great for quotes for the paperback but actually hardly anyone reads book reviews,” Doughty said.

Doughty highlighted how book readership expanded beyond literary festivals through social media, like TikTok, creating new readers.

Doughty prefers smaller literary festivals as the audience attend one event at a time and authors enjoy their undivided attention.

“The problem with the big book festivals - Cheltenham, Hay or Edinburgh - they’re great fun to go to from the social point of view because you meet loads of other authors but quite often, there might be half a dozen events going on at the same time as yours,” she said.

She also saw festivals as an equaliser, not least for new authors gaining exposure.

“Book festivals are such an important way to sell your work to people who have never heard of you.

“Even if you only sell half a dozen copies after a reading, if those half a dozen people tell their book group or tell friends, you’re gradually building word of mouth,” the author added.

Doughty highlighted author positioning in literary festivals was shaped by their books. Apple Tree Yard, which became a hugely successful TV series in 2017, pushed Doughty to huge success.

“When you’re an unknown novelist, you get put on the graveyard shift, on a Sunday morning at 10am or a Tuesday afternoon at 3pm and it can be pretty bleak," she said.

“Whereas suddenly with the success of Apple Tree Yard, I’m being given the Pillar Room at Cheltenham at 2pm on a Saturday.

“It’s a prime slot, you’re selling out to 200/250 people.

“When you have a bestseller and you can pull a crowd of several hundred, it’s very satisfying.”

Doughty nonetheless recognised literary festival attendees were not the most diverse. Yet she felt online events became an equaliser for bringing people together, with hybrid events involving in-person and online audiences.

Though in-person audiences were preferable for Doughty, she recognised online festivals provided equality for those from rural areas and with disabilities.

Despite the cost of living crisis, Doughty was optimistic literary festivals will adapt.

“Books tend to fare better in a recession because they’re relatively cheap," Doughty said.

“It’s cheaper than going to see a film or certainly a lot cheaper than going to the theatre.

“Books are often given as presents if people can’t afford a more expensive present.”

Their cheapness is economically damaging to authors, though Doughty thought the bigger costs were any cuts to the education budget.

“When you get cuts to public services, what that affects are the feeder routes for both audiences and authors," she said.

“If funding for those gets cut, then I think that does have a very bad knock on effect for authors because all authors need a vibrant literary culture to survive.”

Doughty, however, celebrated novels remaining alive and relevant.

“I think as long as people have an appetite for long form narrative, the novel and the culture around it, including festivals, will survive," Doughty added.

“There’s nothing I love more than talking to real readers and in fact when people say it’s exciting to meet a writer, I’m just as excited to meet a reader because they are increasingly projected to be a rare beast.”

From speaking to numerous festival programmers, literary journalists and an author, they all recognised literary festivals face challenges. Even without Covid-19 and a cost of living crisis, the logistical operation was significant and wide-ranging. This required money, though funding sources for festivals were uncertain.

However, there was an acknowledgement literary festivals can be equalisers. Attendees could join online to discover new authors, with festival programmers creating programmes for a specific audience. Authors were able to show their work and ideas to large audiences.

Festival organisers were aware of the demographics of attendees and how this affected festivals. All the festivals were determined to ensure someone’s economic position did not impede their ability to access culture. Despite their optimism, they were aware declining disposable income could affect attendance.

The power of literary festivals in the cultural landscape was apparent when the Covid-19 pandemic struck. Given how fast festivals moved online, adapted to new technology and hosted events, the desire to communicate was clear. There was confidence festivals would remain relevant. The will for culture surely meant a way can be found. Despite needing increased accessibility and battling turbulent economic storms, the future for literary festivals is bright.

Image Credits

SWL Logo: South West Londoner

Wimbledon BookFest: Noah Keate

Edinburgh: Flickr, Ralf Steinberger (CC BY 4.0)

Scottish Lake: Flickr, Martin de Lusent (CC BY 2.0)

Nicola Sturgeon: Flickr, First Minister of Scotland (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Scottish banknotes: Flickr, cowrin (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Wigtown Book Festival: Colin Tennant

Timeline: Noah Keate (using Canva)

Literary Festival Deck Chairs: Geograph, Jim Barton (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Alex Clark Videos: Noah Keate (using Zoom)

International Newspapers: Wikimedia Commons, David Hawgood (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Audience Laughing: Flickr, Plashing Vole (CC BY-NC 2.0)

HowTheLightGetsIn Tent: Wikimedia Commons, Steve Turvey (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Cambridge Literary Festival: Martin Bond

Chiswick Book Festival: Wikimedia Commons, Roger Green (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Sam Leith Video: Noah Keate (using Zoom)

Book Talk: Flickr, Bank Square Books (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Sam Leith SoundCloud: Noah Keate

Boston Book Festival Team: David Dawson

Joy Ellis at Boston Book Festival: David Dawson

James Nicoll at Boston Book Festival: Sue Morrison

Louise Doughty: Wikimedia Commons, Anggara Mahendra (CC BY 2.0)

Books Wrapped in Brown Paper: Flickr, Marco Verch Professional Photographer (CC BY 2.0)

Woman Holding Books: Flickr, Nenad Stojkovic (CC BY 2.0)

Quiz: Noah Keate (using Flourish)