Watch Out for the Spice Bag

Why the Irish-Chinese takeaway is destined for a London love affair

“Dining out in London is incredibly expensive - there’s a danger of it becoming the preserve of tourists and the wealthy few.”

Those are the words of Emma Franklin, food and drink editor, when asked if she’s excited to see what food trend London embraces next.

She’s someone who’s made a career of dining out - few others would have a better instinctive sense of menu prices creeping up and the increasingly ubiquitous presence of American-style tipping culture.

Franklin’s warning about the future of dining out might help explain why the Irish spice bag seems to be taking root in London.

The spice bag unapologetically defies restaurant service, it’s too cool for that. It’s ‘eat it on the go, no fuss, no fork, no bother’, served in a no-frills paper bag that soaks up pools of grease to create spots of translucent stains.

The salt and chilli – known as salt and pepper in the United Kingdom - chicken and chips combo has taken Ireland by storm over the past decade. The spice bag is verging on national symbol status at this point, and it even has an official definition in the Oxford English Dictionary. But can that success be replicated in London?

Ireland’s spice bag pride

Growing up in County Clare, the fastfood furore of my teenage years was the pizza meal deal. For €5, you got a small pizza, chips and a can of coke. On a trip home from London a few years ago, I was collecting my 16-year-old brother from a night out. He asked if we could stop for food. I told him the pizza place would be closed, it was after midnight. He gave me that uniquely teenage ‘do you think I’m a child?’ look, as if pizza had someone gone out of fashion.

“The Chinese is open. I’ll call them now and order a spice bag. You want one?”

That was my introduction to the spice bag. The Chinese-inspired fastfood has swept the comparatively tame pizza and chips deal off the top spot to claim dominance over Ireland’s late-night food scene.

On apps like TikTok and Instagram, there’s an endless stream of spice bag content, with popular Irish creators like Garron Noone pumping out spice bag videos.

TikTok: @garron_music

TikTok: @garron_music

Noone’s ‘England is trying to steal Ireland’s national dish!’ skit taps into something integral to the spice bag phenomenon. Until recently, you could only find it in Ireland. That was its selling point, especially for the hordes of Irish people who have an automatic preference for anything, well, Irish.

Ireland’s patriotism is victimless until one delves deeper, realising some of the motivation behind it is a contempt for anything, or anyone, perceived as English. It’s nationalism dressed up as patriotism to make it palatable for the masses.

Perhaps this is placing too much meaning onto spice bags, however the Irish have a remarkable way of softening the sharp edges of their lingering resentment towards the English. Rarely is it spelled out, yet it is unmistakably felt. Something as mundane as a spice bag can carry far more than its mix of chips and chicken.

As Noone puts it: “I bet the English aren’t even serving it in a bag, [...] they probably eat it with a fork as well.”

Unrequited resentment?

Perhaps the greatest irony is that I have found Londoners to be nothing but excited about the arrival of the spice bag. There was no animosity about the fact that it originated in Ireland. If anything, this was a bonus.

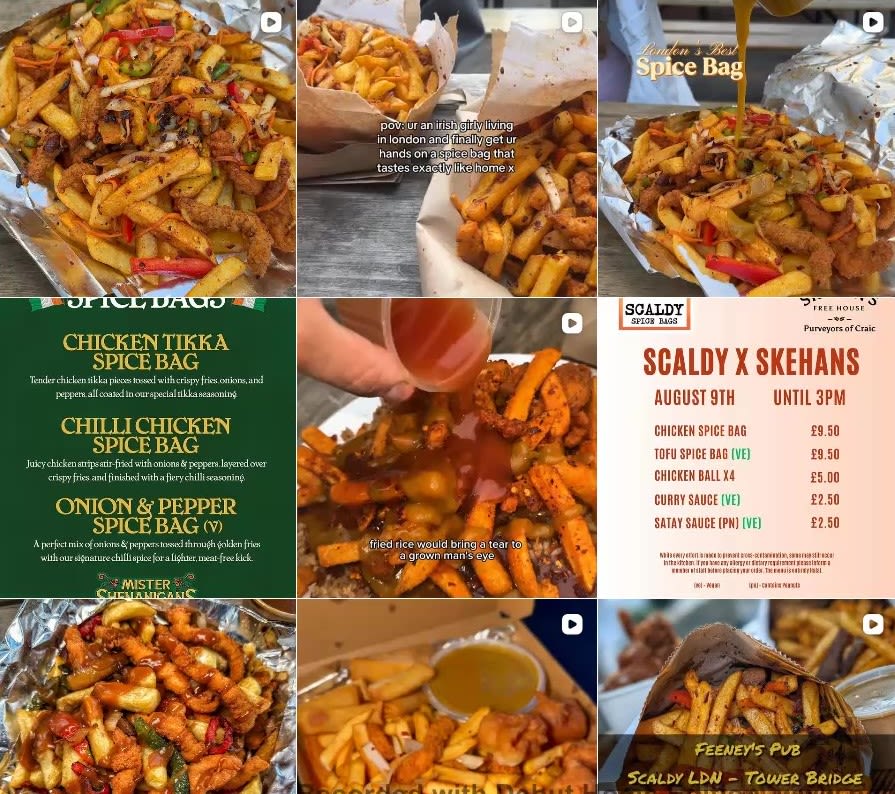

In Feeney's Irish pub near London Bridge, the city's first spice bag specialist, Scaldy, does a thriving trade. Despite the rainy autumn weather on the Tuesday afternoon I visited, the customers were merrily indulging in spice bags and Guinness. Some even seemed to think all spice bags come with a free Guinness.

Ireland’s economic boom in recent years means that GDP per capita is now significantly higher than in the UK, with Brexit Britain languishing behind. Of course, this follows centuries of Ireland being oppressed, making its fiscal fortunes all the more improbable and therefore impressive.

The average Irish household spent

16%

of its

budget

on restaurants and hotels in 2024

The average UK household spent

7.1%

of its

budget

on restaurants and hotels in 2024

In this context, it’s easy to see why the spice bag has found early success in London. Even Wetherspoons has jumped on the trend and now sells a selection of spice bags at budget prices.

“We are always keen to offer customers the widest range of meals.

“The spice bag has proven extremely popular with customers in Ireland – and we are confident that it will also be well received by customers in pubs throughout England, Scotland and Wales.”

Franklin’s right in claiming many Londoners simply can’t afford to dine in restaurants regularly anymore. But life isn’t getting any easier - everyone still wants a treat on a Friday night, or after a long day in the office.

Enter the spice bag: it’s convenience food, it comes ready to eat, the price is upfront, there’s no hidden service charge, and it’s generally cheaper than even a reasonably priced Chinese takeaway. It’s an indulgence fit for Londoners who are being priced out of restaurants.

Franklin suggests spice bags might be a product of their time, rather than a flash of fastfood genius. But by attempting to dispel the mythologising around spice bags, reducing it to merely “salt and pepper chips”, is she dismissing the fact that spice bags clearly resonate not just with the Irish, but with Britons too?

If you’re one of the many Londoners looking for affordable alternatives to eating out, here’s a checklist of everything you’ll need to make a spice bag at home. There are even some tips to make it taste just like the real thing.

Can London handle the spice?

One of the main arguments against spice bags catching on in London is the shift in nightlife culture. In Ireland, ordering a spice bag after a night out is a rite of passage. The greasiness soaks up the alcohol, while the spicy seasoning wakes you up just enough to get home safely. There’s something kind of obnoxious about spice bags, and as most of us know, it’s harder to be obnoxious when sober. Given the UK has lost 37% of its nightclubs since March 2020, it seems sober is becoming the new normal, with half of young adults now choosing no or low alcohol drinks over spirits and beers. But will a decline in binge-drinking, and an uptake in fat jabs, translate into slower sales for spice bags?

Instagram: @kwanghic

Instagram: @kwanghic

Instagram: @kwanghic

Instagram: @kwanghic

Irish Chinese chef, author and entrepreneur, Kwanghi Chan, doesn’t think so. Chan, whose spice bag seasoning is available across Ireland in supermarkets like Tesco’s, believes the salt and chilli combo has a bright future in the UK.

Chan has an interesting story. He was born in Hong Kong but moved to County Donegal at the age of eight. He began helping in his uncle’s Chinese restaurant as a child, explaining that “Like every immigrant family, it was all hands in.”

Chan says the food he and his family ate wasn’t the same as they served. He is an expert in the vast differences between Chinese food and Ireland’s interpretation of it. Irish-Chinese takeaways bastardise traditional flavours, adjusting them to suit Irish tastebuds. This has been such a success that in almost every Irish town and village, you will now find a Chinese takeaway along with a pub and a dusty, underused church.

Chan, now one of Ireland's most celebrated chefs, embodies the country’s story of immigration, offering a counterpoint to the more familiar tale of Irish emigration.

Ireland first welcomed Hong Kong immigrants in the 1950s, before a second wave arrived in the 1990s. As it was a British colony, many spoke English, making Ireland an accessible place to settle. In order to make a living, families set up restaurants and takeaways that paved the way for Irish-Chinese food.

A full circle moment is Irish people now moving abroad to set up spice bag restaurants.

Chan, now one of Ireland's most celebrated chefs, embodies the country’s story of immigration, offering a counterpoint to the more familiar tale of Irish emigration.

Ireland first welcomed Hong Kong immigrants in the 1950s, before a second wave arrived in the 1990s. As it was a British colony, many spoke English, making Ireland an accessible place to settle. In order to make a living, families set up restaurants and takeaways that paved the way for Irish-Chinese food.

A full circle moment is Irish people now moving abroad to set up spice bag restaurants.

One such entrepreneur is Cathal Farrelly, who opened Paddy Wok in southeast London on St. Patrick’s Day, 2025.

The business was bustling when I visited, with customers excitedly tucking into their spice bags. Farrelly says he started Paddy Wok because he missed the taste of home, and thought London could do with a takeaway shake-up.

When I ask him why he thinks Irish-Chinese food has been such a hit, he says “It’s just so different. It’s different from actual Chinese food, it just works well.”

Farrelly says this rather earnestly. This man takes spice bags seriously.

When I ask Chan the same thing, he tells me its simplicity is its success. “It’s just salt and chilli chicken with chips.”

He chuckles to himself, like he’s in on something.

Perhaps the Irishman who is one step removed, growing up in an immigrant family with a different language and different food, can see the spice bag for what it is - or rather, for what it represents: something simple yet delicious, and most of all, daring. I bet London’s going to love it.