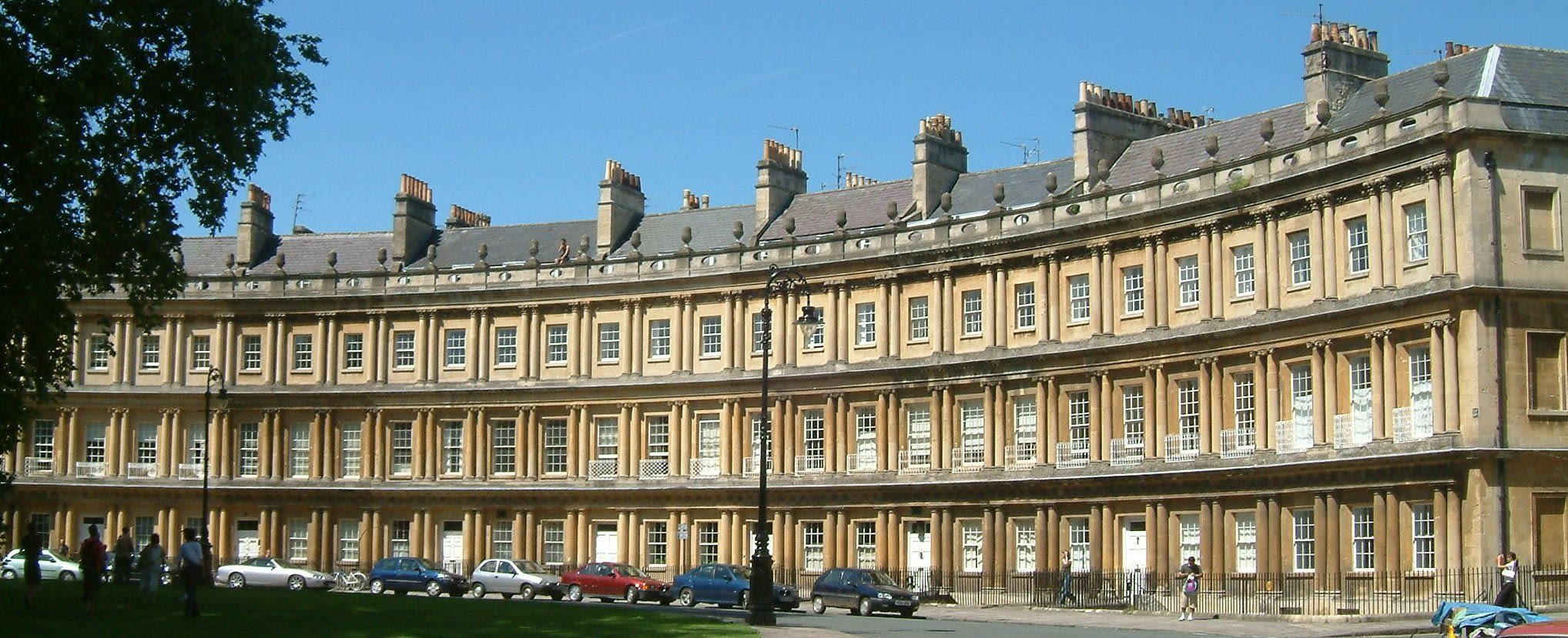

Beautiful Buildings

How the government's radical planning revamp could change the architectural landscape of the UK

As the flag bearers of a tradition which places prudence above almost all other virtues, conservative governments are supposed to baulk at policies that bring about radical change.

Yet new government guidelines for urban planning, currently being piloted in 14 boroughs and which will soon come into force across the country, have been called not only radical, but revolutionary.

Sustainable housing, high quality design, democratic participation, and a complete rezoning of the planning process are among the areas that have been targeted.

One of the more controversial aspects is the inclusion of the word “beauty”, which “will be prioritized in planning rules for the first time since the system was created in 1947,” the Ministry for Housing, Communities & Local Government (MHCLG) announced earlier this year.

To make the guidelines actionable for local councils, the government have gone further than many philosophers would dare by laying out a criteria for defining beauty as it pertains to buildings and public places.

The wheels for this far-reaching policy shift were set in motion by the Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission, an independent body set up to advise government on how to promote high-quality design for new build homes and neighbourhoods.

Co-chaired by Nicholas Boys Smith, founding Director of Create Streets, a social enterprise encouraging urban homes in terraced streets, as opposed to multi-story buildings, and the late conservative thinker and philosopher of aesthetics, Sir Roger Scruton, the Commission’s report was wholeheartedly embraced by the government in January 2020.

Its goal of defining and promoting standards of beauty that communities can agree on is an ambitious one, as one man’s idyllic vista can be the source of another’s utter indifference.

United States Embassy, Dublin, Ireland

United States Embassy, Dublin, Ireland

In his writings on beauty, Scruton said: “Ravishing beauties are less important in the aesthetics of architecture than things that fit appropriately together, creating a soothing and harmonious context, a continuous narrative as in a street or in a square, where nothing stands out in particular, and good manners prevail.”

This suggests that far from existing in a vacuum, architectural beauty is best understood holistically, by the way it relates to its environment.

According to this view, consistency and harmony take precedent over experimentation and architectural freedom for developers.

Architectural disharmony: the charm and vernacular of a Central London street eclipsed by The Shard building

Architectural disharmony: the charm and vernacular of a Central London street eclipsed by The Shard building

In a culture that places a high premium on individual freedom, and in the backdrop of the ever-increasing, post-war architectural envelope pushing that has left us with iconic buildings and zones throughout London, from the Barbican to Canary Wharf, this is quite a sea change.

Echoing Scruton, the National Design Guide has defined a “well-designed new development” as one that is “integrated into its wider surroundings, physically, socially and visually.”

Notre-Dame Cathedral, Paris

Notre-Dame Cathedral, Paris

York Minster glimpsed from Low Petergate, York. Source: Peter K Burian

York Minster glimpsed from Low Petergate, York. Source: Peter K Burian

How will it work in practice?

Harmony with the local vernacular is one of many criteria in this design code, which will help councils to come up with their own guidance, but in the absence locally derived guidance or codes, the government has said that the National Design Guide and National Model Design Code should be followed.

Put simply, this or a similar definition of beauty will soon “be an essential condition for planning permission,” as the Living with Beauty Report states.

Gasholders, Kings Cross, London

Gasholders, Kings Cross, London

Suffice to say, some experts are sceptical about how such an all-encompassing brief will manifest in reality.

Jonathan Solomon, property consultant and former global head of real estate at Clifford Chance law firm, told SWLondoner that while it is laudable in a number of ways, the new legislation is quite “radical” and “over ambitious.”

He said that improving design and making the planning process more democratic are worthy objectives, and that he has no problem with using a general concept like beauty, providing “it drills down into some policies that everybody can understand, and that you can then apply on a level playing field.”

He continued: “I like the idea of trying to incentivise good design, but the trouble is, the interpretation of good depends on who you speak to: some people like to replicate Victorian terraces, but then if you were to adopt too conservative interpretation of good design it would, for example, preclude the Gasholders residential development in Kings Cross where space was developed within the old iron structures – this is fantastically creative cutting edge design.

“This may not appeal to some people and it has no relationship, particularly, with the Victorian history of Kings Cross, but I think it would be a real shame to try to close down cutting edge architecture like that.”

Kings Cross, London

In the National Design Guide, apartments in areas such as Highbury Gardens, Islington, are sited as examples of good practice for being “designed in a traditional style in response to the local identity,” yet there is no mention of more modern-style developments like Kings Cross.

Victorian Terraced Houses, Highbury, London

Victorian Terraced Houses, Highbury, London

"Father of skyscrapers", Louis Sullivan, circa 1895

"Father of skyscrapers", Louis Sullivan, circa 1895

Ornamental saturation: Rococo interior of Wilhering Abbey, Austria

Ornamental saturation: Rococo interior of Wilhering Abbey, Austria

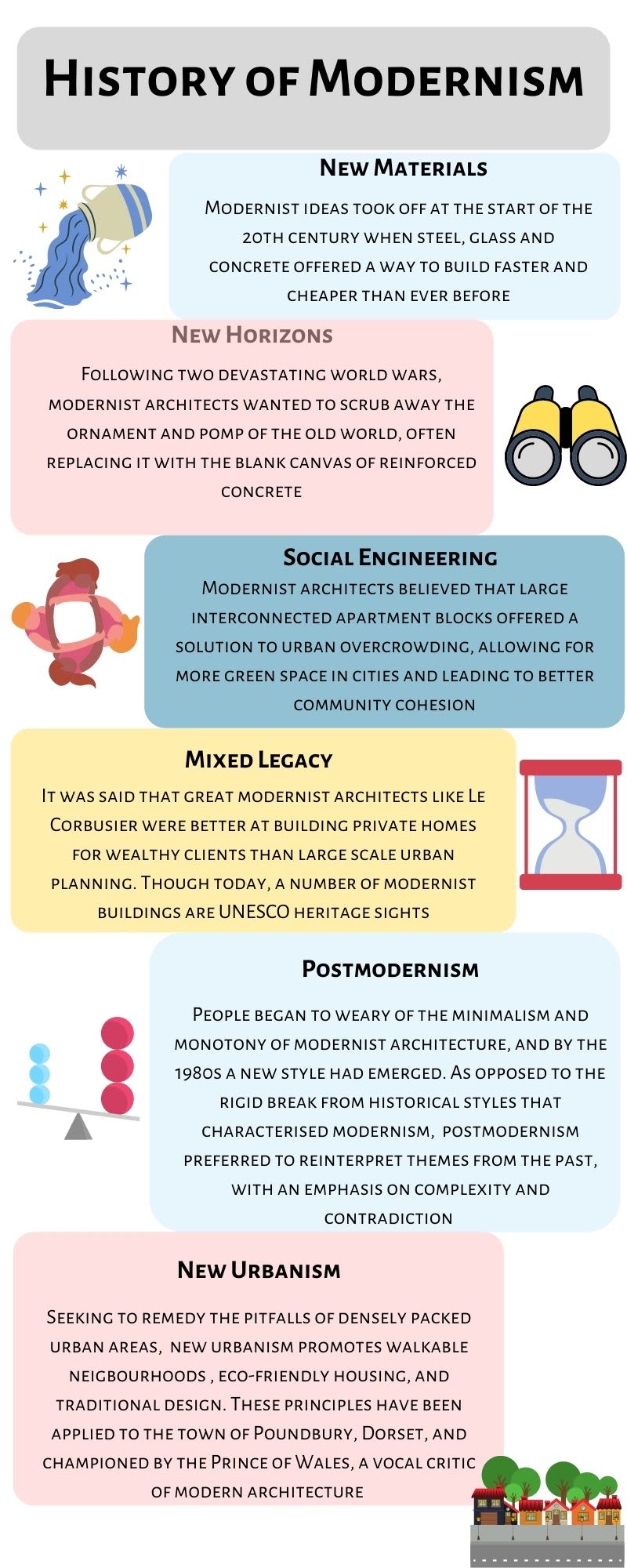

Not far beneath talk of harmony with the local vernacular lurks the elephant in the room of stylistic preference.

The policy will have to contend with the fact that there are towns and cities across the UK where modern developments abound, creating ambiguity around what the local vernacular actually is.

Once the debate moves over into the thickets of personal taste, the chances of arriving at a consensus are remote — as a century-and-a-half long slugging match among architectural heavy weights can attest.

Dubbed the “father of skyscrapers”, Louis Sullivan is the architectural antithesis to Scruton and Boys Smith: he believed that beauty was present when a building's observable features, or form, followed its function.

A quintessential example of form follows function: The Wainwright Building, St Louis, Missouri, built by Louis Sullivan.

A quintessential example of form follows function: The Wainwright Building, St Louis, Missouri, built by Louis Sullivan.

In fairness to Sullivan, he may have subscribed to a loftier idea of functionality than he is given credit for.

Outlining his vision for these prototype skyscrapers, he said: "It must be tall, every inch of it tall. The force and power of altitude must be in it, the glory and pride of exaltation must be in it. It must be every inch a proud and soaring thing, rising in sheer exultation that from bottom to top it is a unit without a single dissenting line."

This sounds more like an homage to the ambitious dynamism of 20th century American commerce than a bland prescription for how to build serviceable office space.

The German architect Adolf Loos also took up the modernist banner in the early 20th century, writing an essay called Ornament and Crime, a polemic against ornamental design that Loos claimed flitters in and out of fashion, resulting in a colossal waste of time and effort on things that will inevitably be discarded.

Reasoning from the well-worn racial analogies of the time, Loos derided ornamentation as the equivalent of the tattoos of the Papuan tribes of New Guinea, who he said were “not evolved to the moral and civilised circumstances of modern man.”

A glance at Loos’s Christmas tree would surely have revealed the absurdity of this kind of ornamental puritanism to even the most immoderate of modernists.

Then finally came Le Corbusier, the Swiss-French architect whose most famous maxim, “A house is a machine to live in,” perhaps best sums up what traditionalists find so objectionable about the modernist spirit: it ignores the value in beauty for its own sake, as a good independent of its function.

In other words, a home is not merely a means to an end, but an end in itself.

Secretariat Building, Chandigarh, India: built by modernist architect and urban planner Le Corbusier, who declared: “The masonry wall no longer has a right to exist.”

Secretariat Building, Chandigarh, India: built by modernist architect and urban planner Le Corbusier, who declared: “The masonry wall no longer has a right to exist.”

That’s not to say there is a one size fits all model, though, as many people, like architect, modernist, and Barbican resident, James Munro, find beauty in more modern settings.

Commenting on the modernist landmark he calls home, James said: “I guess I'm biased, I've lived here now for about 16 years.

“I think it's amazing, strong community, we don't all agree with each other, we've got a residence forum that sparks a lot of discussion and arguments and whatnot, but we've got a vibrant and really fantastic cross section of community.”

A critique often levelled at modernist architects is that their grand designs – typically large concrete apartment blocks, connected through neglected communal areas and windswept walkways – are conceived as social utopias for other people, while the architect opts to live in a nice Victorian townhouse or Georgian cottage.

Not so with James, who has put his money where his mouth is.

He is concerned about the new guidelines, particularly their vague references to traditional styles and materials, as he believes they are based upon a mischaracterisation of modern architecture.

James said: “I don't necessarily object to the use of traditional materials.

“These are used by modernists, it’s not like we're reinventing the wheel, we are using timbers and brick and stone and metal, and all those things that have existed for years, it is just how you materialise that in a design at the end of the day.

“I don't think anyone's trying to make everyone live in glass boxes, that isn’t part of the vernacular in the UK.”

Secretary of State for Housing, Communities & Local Government Robert Jenrick seems to think otherwise, and has cited polls showing strong public dissatisfaction with places that were built after the planning system came into being in 1947 as a kind of democratic mandate for the radical overhaul he is overseeing.

He wrote in The Times: “In cities, urban planning since the war has at times been a disaster.

“We have some of the best designers and architects in the world. Despite the post-war mistakes, we have one of the finest built environments — why else do legions of international tourists normally flock to our market towns and cathedral cities?”

Britain’s cathedral cities are indeed a source of attraction for a wide cast of characters, as we learned in the grimly tragicomic circumstances surrounding the poisoning of Sergei and Yulia Skripal by two heavy-set, ostensible enthusiasts of Gothic architecture.

But other areas are also a point of attraction, like the Barbican, or the recently rejuvenated Kings Cross, whose amenities are forecast to attract up to 20 million people per year, according to Nashbond property advisory group.

A modernist triumph: Barbican Estate, City of London

A modernist triumph: Barbican Estate, City of London

A modernist triumph: Barbican Estate, City of London

A modernist triumph: Barbican Estate, City of London

Salisbury Cathedral, England

Salisbury Cathedral, England

Roof-fitted solar panels

Roof-fitted solar panels

Eco-friendly 3D printed house: TECLA, made from mainly earth and water. Source: Alfredo Milano

Eco-friendly 3D printed house: TECLA, made from mainly earth and water. Source: Alfredo Milano

Speaking to SWLondonder, Labour councillor and Lead Member for Regeneration, Property and Planning for Brent Council, Shama Tatler said she thinks the emphasis on beauty is misplaced.

Cllr Tatler said: “I think they should have focused on the idea of sustainability, conversations about carbon free or carbon neutral development, and about existing concrete buildings that are actually usually energy inefficient, rather than the sort of archaic, basic historical view of what's beautiful.

“A tree lined street is lovely, but it doesn't serve the purpose of reducing overcrowding.”

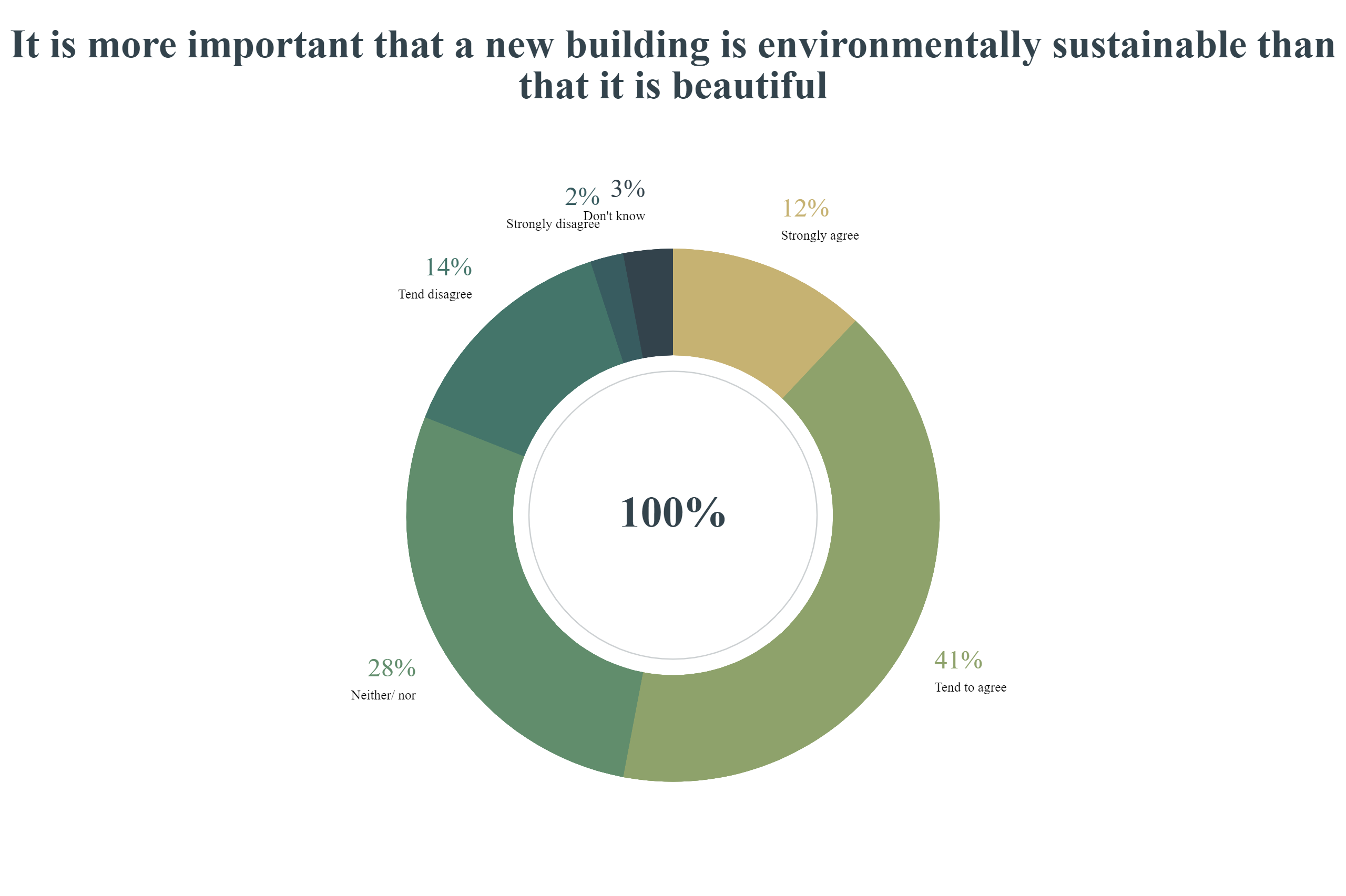

Sample: 1,043 adults in England (Aged 15+). Data source: Ipsos MORI

Sample: 1,043 adults in England (Aged 15+). Data source: Ipsos MORI

An Ipsos MORI poll taken in 2014 found that most adults in England thought it was more important for a home to be sustainable than beautiful, supporting Cllr Tatler's point.

But this may be false dichotomy: the new emphasis on beauty is driven partly by the idea that buildings which are beautiful outlast those that aren’t, and so not only do they enhance the scenery, but cause less environmental fallout in the long run.

Taking a different view, Cllr Tatler said: “I think that the more modern buildings are more energy efficient. The energy it takes to heat an apartment or new build is much less than it takes to have an old Victorian building.

“So, there are pros and cons, but what I've seen from new buildings is that people are much happier with energy efficiency, better security and maintenance and so on.

“I think that is an important part of the conversation, as well as the actual structure of these buildings. The maintenance cost of older buildings is also something that we need to factor in.”

There is also a sampling bias, as it tends to be the better quality older buildings that have stood the test of time, while shoddier ones have not.

Beauty as a science?

Climate concerns aside, tastes change over time, and as we have seen, Cllr Tatler is not alone in thinking the aesthetic quality of design is “very subjective.”

Despite being the only part of the debate that people seem to be in agreement on, a budding new area in data science suggests it may not be as simple, or rather, as complex as that.

Research from the University of Warwick entitled, “Might beautiful places have a quantifiable impact on our well-being?”, argues just that.

It found that “across the entire English data set, inhabitants of more scenic environments report better health”, and the results hold even after controlling for different levels of wealth, access to services, and air pollution.

The authors acknowledge that definitions of “scenicness” vary, but with “over 1.5 million votes rating the scenic quality of images covering nearly 95% of the 1 km grid squares of Great Britain,” they have a strong claim to have gathered something of a consensus.

Further research found that, “as well as natural features such as ‘Coast’, ‘Mountain’ and ‘Canal Natural’, man-made structures such as ‘Tower’, ‘Castle’ and ‘Viaduct’ lead to places being considered more scenic.”

If aesthetics is indeed transforming from an art into a science, it could explain the government’s confidence in declaring that it can “make judgements about beauty."

But it also provides a way to empirically judge the effectiveness of the new policies — particularly if they live up to their promise of enhancing well-being.

Embedded within these answers will be new questions.

If there is a negative causal link between ugly environments and well-being, then, once better defined, should they not be taxed in the same way as say, pollution, carbon, or any other economic externality?

As this field develops, its implications may reach beyond planning decisions and cause us to fundamentally rethink the way we relate to our surroundings.

Unlike the great modernists of the 20th century, Scruton notes how our ancient Greek forbears thought of beauty as an ultimate value, comparable with truth and goodness.

The imperative of beauty therefore spilled over into all endeavours, and legacy of this is woven into the fabric our language: the word poetry derives from the Greek word poiesis, meaning to make things.

In an age where people are increasingly at odds about what is true and what is good, a shared sense of what is beautiful would be not only thoroughly refreshing, but subversive.

Image Credits

Article Images:

1) Bath Circus: Christophe Finot, via Wikipedia, reproduced under Creative Commons license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5/deed.en

2) York Minster: Source: Peter K Burian, via Wikipedia, reproduced under Creative Commons license: https://creativecommons.org/share-your-work/licensing-considerations/compatible-licenses

3) Salisbury Cathedral: Author: Antony McCallum, source: WyrdLight.com, via Wikipedia, reproduced under Creative Commons license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en3)

4) Louis Sullivan: Source: Wikipedia, reproduced under public domain as image was published (or registered with the U.S. Copyright Office) before January 1, 1926, meaning copyright has expired in both the US and UK

5) Wainwright Building: Source: Wkipedia, reproduced under public domain as it is a work prepared by an officer or employee of the United States Government as part of that person’s official duties under the terms of Title 17, Chapter 1, Section 105 of the US Code

6) Wilhering Abbey: Source: Uoeai1, via Wikipedia, reproduced under Creative Commons license: //creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en

7) Secretariat Building: Source: Lian Chang, via Wikipedia, reproduced under Creative Commons license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en

8) Solar Panels: Punjnak, via Wikipedia, reproduced under Public Domain unconditional reproduction

9) Tecla House: Source: Alfredo Milano, via Wikipedia, reporduced under Creative Commons license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/deed.en

10) Henrika Šantel: Source: Wikimedia Commons, reproduced as author died in 1940, so this work is in the public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 80 years or fewer

11) Glenfinnan Viaduct: Nicolas Benutzer, via Wikipedia, reproduced under Creative Commons license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5/deed.en

Quiz Images:

1) Žižkov Television Tower: Author: Thomas Ledl, sourced via Wikipedia, reproduced under Creative Commons license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en

2) Weissenhof building: Author: Shaqspeare, sourced via Wikipedia, reproduced under Creative Commons license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en

3) Bauhaus building - Wassily Chairs: Author: Kai ‘Oslwald’ Seidler, sourced via Wikipedia, reproduced under Creative Commons license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en

4) Park Hill Flats: Author: Julian Varas, sourced via Wikipedia, reproduced under Creative Commons license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en

5) Islington Town Hall: Author: Alan Ford, sourced via Wikipedia, reproduced under Public Domain unconditional reproduction

6) The Carson Mansion: Author: Cory Maylett, sourced via Wikipedia, reproduced under Creative Commons license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en

7) Upper Baggot Street: Author: DubhEire, sourced via Wikipedia, reproduced under Creative Commons license: https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/deed.en