BIG BEN: The ultimate British political symbol?

100 years since the bells first rang out on BBC radio - the story of the clock which came to encapsulate the nation's political soul

New Year's Eve 1923. The December night marked not only the end of the year when frozen food was invented and the start of the year when the first round-the-world flight took place, but also the beginning of a much-loved tradition in British broadcasting and politics.

For the first time, the sound of the bells inside the Elizabeth Tower, commonly called 'Big Ben', was heard beyond Westminster when the BBC broadcast the chimes to bring in the new year. And so began the tradition of the bongs ringing out before BBC radio news bulletins, and the unbroken association of this central London clock tower with British news and politics.

The resulting global notoriety of the tower has led many to the tempting conclusion that it is, perhaps, the ultimate British political symbol.

But the story of Big Ben over the past century is chequered, and historians believe that there are parallels to be drawn between the physical state of the clock over the years and the political mood of the country at the time.

Credit: BBC via YouTube

Credit: BBC via YouTube

Credit: BBC via YouTube

Credit: BBC via YouTube

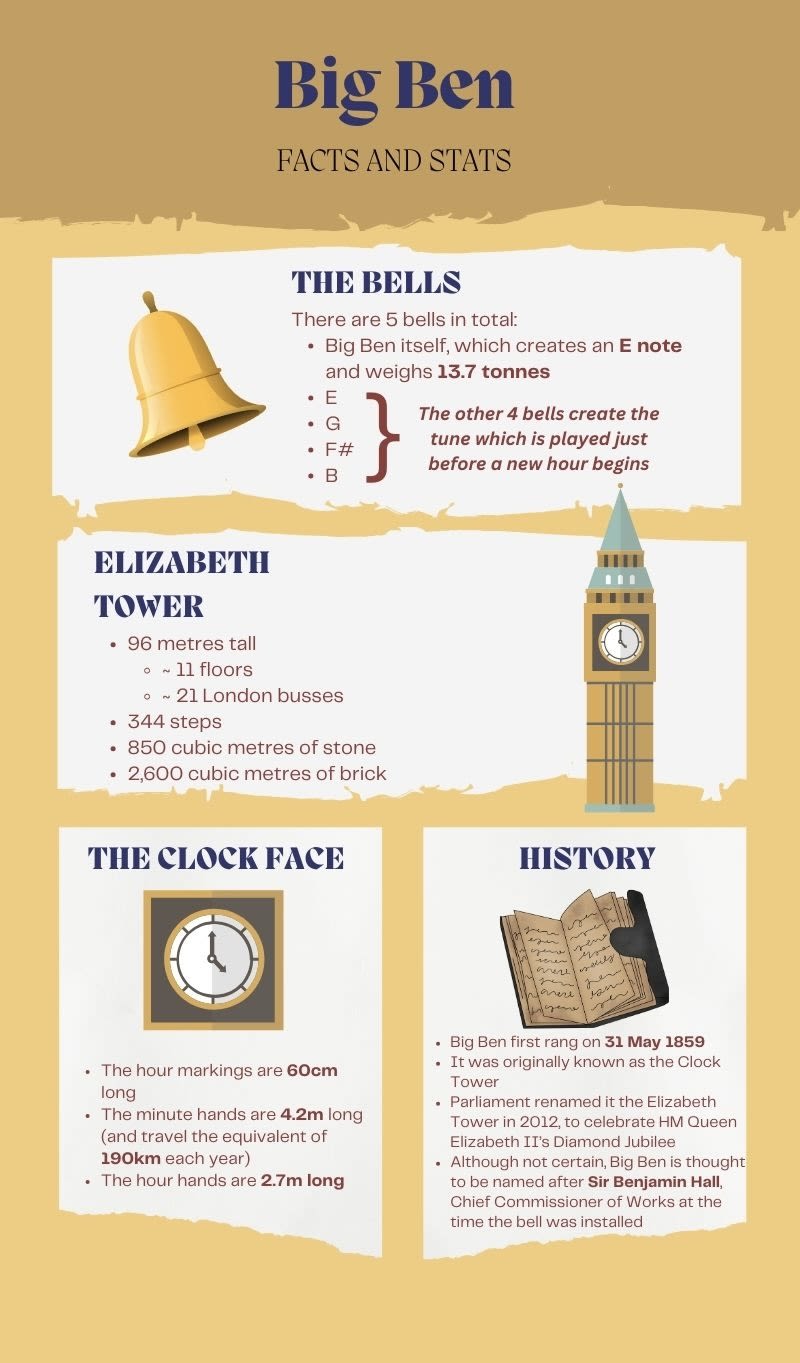

Big Ben is technically not the name of the tower and clock which attract millions of tourists each year, but more specifically the one bell which is struck at the start of each hour to indicate the time.

It is this bell, which creates an E pitch note, that has become so widely associated with news and moments of national political importance.

The sound rings out at the start of every news bulletin at 6pm and midnight on BBC Radio 4, and is broadcast live from the microphones inside the tower (each and every day). It also plays a critical symbolic role in other events, particularly those broadcast by the BBC including general election nights and coverage of Remembrance Sunday.

"When I hear Big Ben there is a sense of history"

Few people's voices are known to many beyond their circle of family and friends. Perhaps colleagues and neighbours too. That's not the case for Jane Steel, BBC Radio 4's Chief Announcer and newsreader for a weekly audience of more than nine million people.

"On air, I’m seconds away from telling everyone the news of the day and there’s usually a frantic last minute flurry of activity," she says.

"People are rushing to their seats, scripts are rustling and then suddenly everything goes still and everyone falls silent, eyes fixed on the second hand of the clock ticking towards the first chime of Big Ben.

"When I hear Big Ben there is a sense of history. Every day for a hundred years Big Ben has been chiming at 1800 and someone has announced the news: huge global events, alongside domestic stories, political spats, deaths of well-known people, sporting triumphs and usually a story or two to make you smile.

Steel is in the ear of millions when they're sipping their morning coffee, or driving home from work, or as they doze off to sleep - moments that are small and frequent yet deeply personal. A job that requires not only a sensitive tone and conviction in oneself, but also emotional intelligence to recognise the importance of informing people with clarity and confidence.

"When I listen at home, Big Ben brings with it a sense of suspense, drama and authority," she continues.

"What will the top stories of the day be? Like a drumroll heralding an important announcement, the chimes signal the news is coming but then make us wait to ensure everyone’s full attention."

"As soon as you start thinking about politics and the fabric that represents politics such as Big Ben, it's almost quite hard to fight off the symbolism"

The bells which play to millions on air have fallen silent several times in the last century. During the war, the parliamentary estate where the tower stands suffered severe damage. On 31 December 1961, heavy snow caused Big Ben to ring ten minutes late, causing confusion as the new year was welcomed in London. The clock also stopped the day before the Labour Party's landslide 1997 general election victory.

Two stoppages, however, are studied with particular interest: 1976-77 and 2017-23. Historians cannot help but observe that Big Ben stopping at these moments is representative of more than simple mechanical failures, but a deeper reflection of the political climate at each time.

Phil Tinline, a political historian and author of The Death of Consensus: 100 Years of British Political Nightmares, said: "As soon as you start thinking about politics and the fabric that represents politics such as Big Ben, it's almost quite hard to fight off the symbolism.

“A symbol is something that is simultaneously literal and metaphorical, so if the fabric of democracy is decaying at the same time that the physical building is decaying - it is a perfect example.”

1976-77

In 1976-7, a major malfunction in the chiming mechanism caused Big Ben to be out of service for 26 days over nine months until May 1977.

Meanwhile, the country was in a state of economic panic as prime minister Jim Callaghan was forced to take a loan from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the National Front was on the march sparking racist violence.

It seems not suspicious but rather almost poetic that one of the nation's foremost symbols of political stability and global power was in desperate need of repair.

“Any physical representation of crisis breakdown at that time is right there,” Tinline says.

2017-2023

Fast forward 40 years and Big Ben’s chiming is once again halted for repairs in 2017, which went on to cost £80m. This time, though, it garnered considerable political attention.

As the UK approached its date of departure from the European Union in January 2020, Prime Minister Boris Johnson made it a personal mission to ensure Britain’s foremost political symbol was back in action for the occasion. A mission, it is worth underlining, which failed.

Despite Johnson brandishing his lyrical pledge that he was “working up a plan so people can bung a bob for a Big Ben bong”, the bells did not return to regular service until January 2023.

Brexit campaigners demanded it was restored in time for the UK's formal departure because of its political symbolism. Whilst this failed in the case of January 2020, it did ring out when the country formally left the EU's single market and customs union at the end of 2020.

Brexiteers decried the fact that “the most iconic timepiece on Earth, which is Big Ben”, was silent for the moment of national history.

Away from the cut and thrust of frontline politics in the late 2010s, the news rolled on and the BBC had to broadcast pre-recorded chimes on its programmes rather than taking the sound live from the tower at 6pm and midnight.

BBC Radio 4's spokesperson, commenting on the return of the live broadcasting of the bells in 2023, said: "We’re delighted to have them back. We know how much our audience enjoys hearing them, providing a moment of resonance and adding texture to the day."

Over nine million listeners tune into BBC Radio 4 each week, and the news bulletins now once again sound as they always did.

But why did the tradition of the bells being broadcast on the radio begin in the first place?

“If you think about the world in which the BBC was invented, to play the bells must have been a very specific choice,” Tinline says.

Watch the video below to hear his analysis.

The BBC and Big Ben: a carefully forged association?