Bordering on Belonging: The experiences of irregularised migrants under the UK’s hostile environment

The stories of those living undocumented in the UK

Living as an irregularised migrant in the UK

The Migration Observatory, an Oxford University project that conducts research into immigration and migration in the UK highlights the difficulty in defining an irregular migrant.

It said: “There is no legal nor broadly accepted definition of an ‘irregular migrant’, though the term is commonly used to refer to people who are in the UK without the legal right to be so.”

On the topic of irregular and or undocumented migrants, the Windrush Generation may spring to mind for many.

The Windrush Generation is a group of people who arrived in the UK from the Caribbean between 1947 and 1971, on the premise that they could reside in the country lawfully.

They undertook vital work including within the public sector to assist with the country's post-war labour shortage.

They believed they were British citizens until 2018 when a large-scale Windrush Scandal revealed that the very same people were being detained and deported due to a lack of legal paperwork.

The Home Office is now promising to rectify the mistakes that were made through various compensation schemes.

However, there are many migrants, like that of the Windrush Generation who currently reside in the UK unlawfully – meaning they do not have the right to rent, work, access universal healthcare, or marry.

In September 2020, a controversial measure was put in place called the Right to Rent scheme.

Under the scheme, landlords are responsible for immigration checks, and certain migrants are unable to rent at all due to their irregularised status.

Some of the migrants featured in this piece have been fighting for citizenship for over ten years – and believe they are in this position due to deceit and abuse of power in the early stages of seeking asylum.

Credit: John Englart, Flickr

Credit: John Englart, Flickr

Numbers tell a story

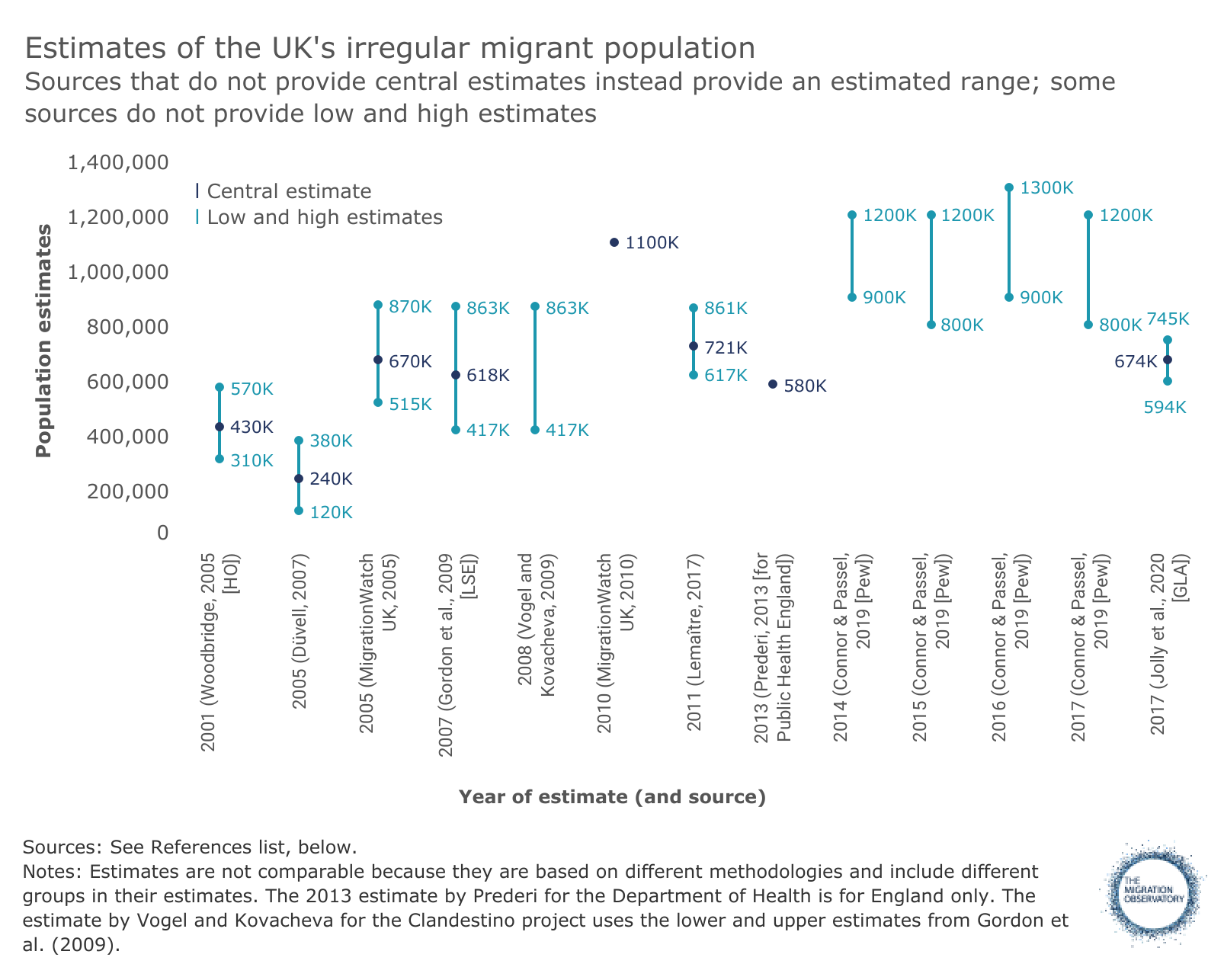

In the United Kingdom, it is difficult to estimate how many undocumented and or irregular migrants live here.

In 2005, a Home Office report estimated that there were between 310,000 to 570,000.

The most recent estimation was made by the Pew Research Center citing there were 800,000–1.2 million unauthorised migrants in Britain in 2017.

However, The Migration Observatory is quick to point out: “Trying to estimate the number of irregular migrants in a country confronts the challenge of counting people who do not wish to be found.

“That is why attempts at estimation have been described as ‘counting the uncountable’.”

Source: The Migration Observatory

Source: The Migration Observatory

What is the UK’s Hostile Environment Policy?

The Hostile Environment Policy is a set of policies designed to force “unwanted” migrants to leave, including administrative and legislative measures designed to make staying in the United Kingdom as difficult as possible for people without leave to remain.

It was introduced in 2012 by then Home Secretary Theresa May who said at the time: “The aim is to create, here in Britain, a really hostile environment for illegal immigrants.”

Under the current Home Office, it is a criminal offence to aid undocumented migrants, which could include providing humanitarian assistance.

Back in May, a BBC documentary entitled ‘Am I British?’ shone a light on the complexities that come with being undocumented in the UK, and stirred a national conversation around the UK’s immigration policy.

Source: BBC, Panorama

It focused on the struggles of settling in the UK and trying to secure ‘Indefinite Leave to Remain’, meaning you can stay in the UK without any restrictions after a ten-year period.

The documentary explores the financial pressures that come with the ten-year route.

Immigration is a point of contention across the UK right now, with media outlets reporting this month a record number of 482 migrants crossed the channel in a single day.

According to Home Office figures, there have now been 10,711 arrivals in more than 440 boats in 2021 alone.

With that in mind, I spoke to three irregularised migrants in differing situations to find out more about the diverse experiences of migrants in the UK, and the very unique problems they face day-to-day.

Ashiq’s Story

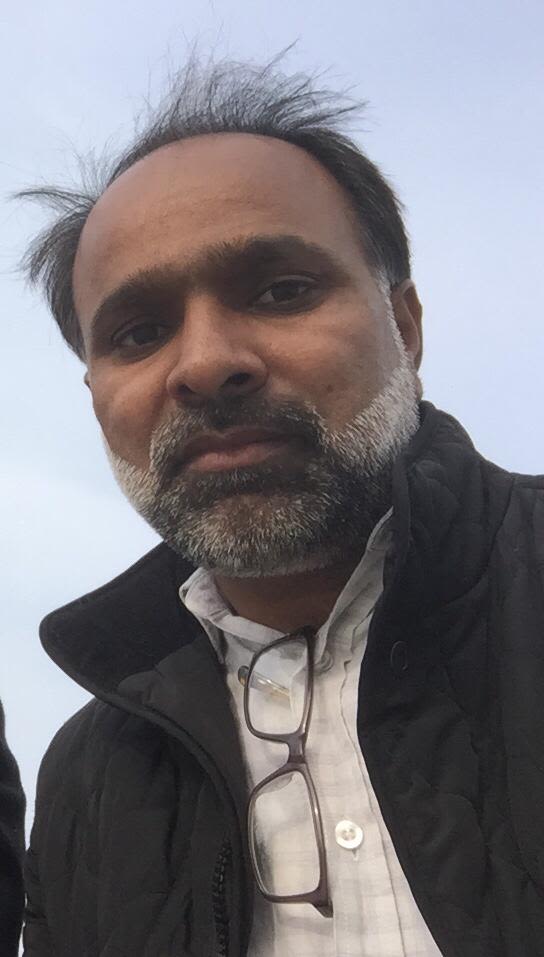

Ashiq, 49, had little to no idea that a dispute with his cousin back in Pakistan would lead him to where he is now – in a decade long battle to become regularised under UK law.

“In 2008 I had a dispute with my cousin over property back in Pakistan. Things turned sour and my life was threatened after being attacked and stabbed. I decided then I had to leave Pakistan,” he told me.

Ashiq arrived in London on a student visa with a plan to contribute to the city.

He enrolled in a postgraduate diploma course in business management in 2011.

Soon after his arrival Ashiq approached a solicitor to ask for assistance in securing asylum in the UK.

The solicitor at the time recommended he wait, otherwise, he could find himself in a precarious situation if the UK government were to inform the Pakistani government of his whereabouts.

Unable to speak English very well, and with little knowledge of the asylum system, Ashiq took this advice and waited.

Eventually, he asked for help again, this time the solicitor agreed and filed an application on Ashiq’s behalf under Section 8 ‘a right to respect for one's private and family life'.

After six to eight months, the application was rejected.

Ashiq paid £2,500 to appeal, only to later find out that Article 8 was not the right defence for his case, as he had no family in the UK at the time.

“I was so stupid, I had no reason not to believe what I was being told, I knew nothing and I was naive,” he admitted.

The firm Malik Law Chambers has since been shut down by its regulator, meaning it cannot comment on the allegations.

The Solicitor Regulation Authority (SRA) cited the reasons for the closure: “There is reason to suspect dishonesty on the part of Dr Akbar Ali Malik and on the part of Mr Imtiaz Ali, the firm’s managers, in connection with the firm’s business.”

It’s been 10 years since Ashiq came to the UK, he told me: “I can’t rent. I can't get access to the NHS. I can't do anything. It’s worse than being a prisoner.

“As you can imagine I’m suffering from very bad depression.

“I just want this nightmare to be over – but ultimately in this country if your status is not regularised, nobody trusts you.

“We do not become irregular by choice, it is this system that the Home Office operates in that makes us irregular.

“But undeniably, this country has given me a chance to survive in the universe. It’s a very nice country and I would never speak ill of it, it’s given me life. However, I ask the Home Office to have compassion, because at the moment I am only experiencing cruelty.”

Ashiq reflected on the difficulties he faced back home in Pakistan

Credit: Ashiq

Credit: Ashiq

Credit: Ashiq

Credit: Ashiq

Consolata's Story

Consolata, 47, originally from Zimbabwe was travelling back to the UK in 2009 from a work trip in Paris when she was detained at Gare du Nord station in Paris and deported.

That was the moment she found out she was irreguralised.

She had arrived in London in 2002 on a student visa.

She said: “When I first decided to move here things in Zimbabwe were going downhill, but also I came to study and be with my family including my aunt who was already here.

“I had a good job back in Zimbabwe but I could see things going the wrong way there.”

Zimbabwe was on the brink of economic collapse at the time, and Consolata had dreams of owning her own business and starting a family.

She met someone who was also Zimbabwean, fell in love, married nine months later, and had a daughter.

Her husband at the time suggested she leave her temporary student visa and join him on a spouse visa.

Over the course of their marriage, her husband was in charge of renewing the visa and keeping her in the loop with any changes.

In turn, the Home Office only ever conferred with the main applicant (her husband).

Four years later, Consolata’s marriage broke down, and the pair separated.

She admitted: “My husband was in charge of the renewals of the visa, he controlled all of that. I didn’t know anything about it. So when we decided to separate, that's when everything went pear-shaped.

“He told me I still had a few years until I would need to deal with my own visa, and I believed him.

“Whilst I was still on his visa he then went on to apply for Indefinite Leave to Remain without me knowing.

“I didn’t know it then but that would be the beginning of my troubles because that cancels any other visa that he previously had.”

Fast-forward to 2009 at Gare du Nord station, Consolata was told that her visa had been curtailed and she would not be able to return to London where her five-year-old daughter was waiting for her.

She was deported to South Africa where she stayed for five months and tirelessly fought to come back.

She eventually returned through an Access to Child visa, but by that time she had lost her job, savings and was “plunged into debt”.

She described her return to London: “On my Access to Child visa, I did not have access to any funds, I came back to the UK and was behind on council tax and rent.

“It was all too much.

“It's like, all your strength is sucked out of your system and you just don't know what to do. For the first year back I was in limbo, whilst trying to raise money quickly for the visa application that I had to make.”

Consolata believes she has spent over £8,000 on Indefinite Leave to Remain applications since she first began the process.

Applications currently stand at £2,389 each.

Since then she has been campaigning against “visa abuse” – when a dependent is not kept informed about their status on a spouse visa.

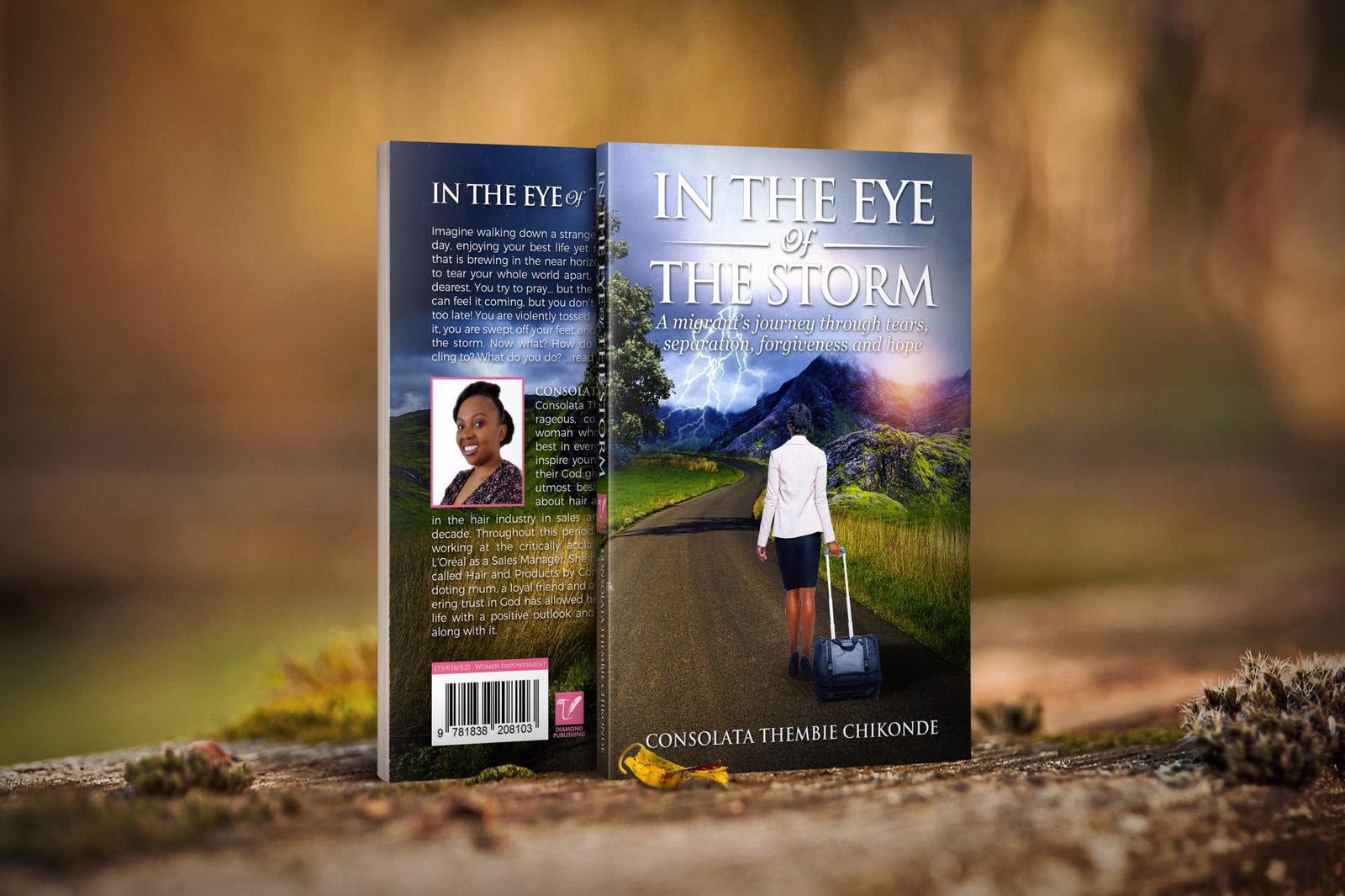

She has since written a book ‘The Eye Of The Storm: A migrant’s journey through tears, separation, forgiveness and hope.’

As we near the end of our conversation she said: “Through my campaigning, I want to fight and make sure no one has their livelihood controlled in this way.

“The system enables abusers to keep abusing their victims.”

In March, Consolata was finally granted British Citizenship and is now happily living with her new partner and two children.

Consolata talked about the uncertainty that comes from living as an undocumented migrant

Credit: Consolata

Credit: Consolata

‘The Eye Of The Storm: A migrant’s journey through tears, separation, forgiveness and hope.’

‘The Eye Of The Storm: A migrant’s journey through tears, separation, forgiveness and hope.’

Jack’s* Story

Jack*, 40, has been in the UK for more than 10 years.

He arrived at the age of 21 from Malaysia to undertake an engineering degree.

He then went on to complete a master's degree in technology management.

He had big dreams of going on to complete his engineering charter training.

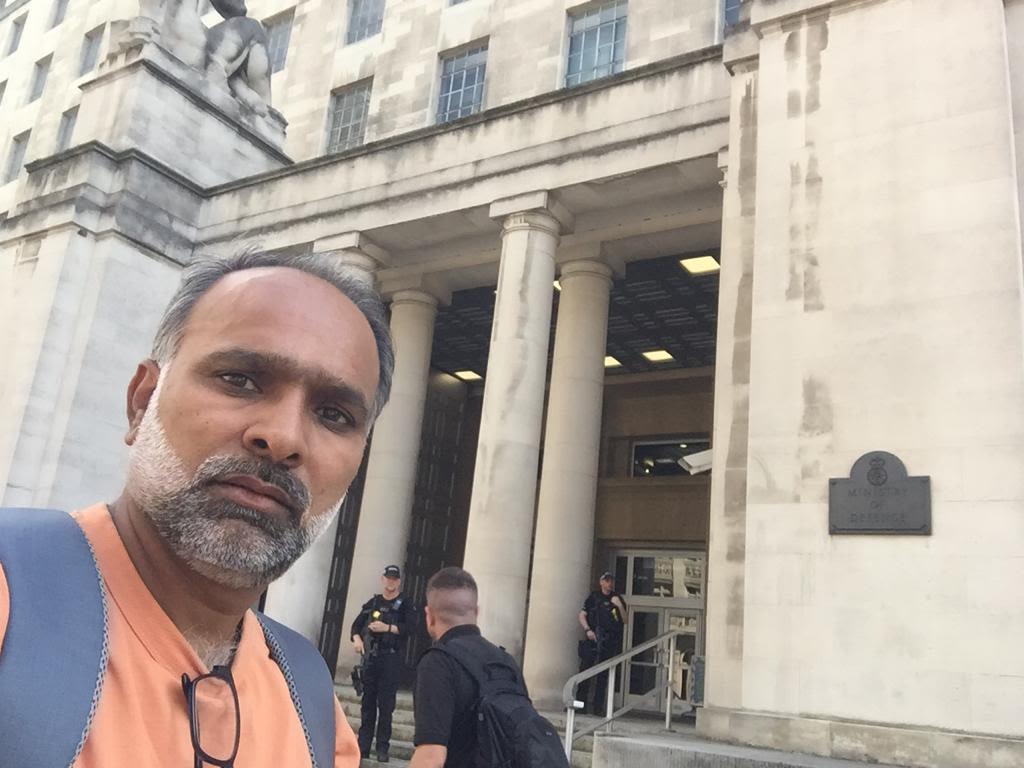

One day he was walking down the street and saw in a solicitor firm’s window an advertisement stating that anyone born before 1983, and whose fathers were born in certain areas before Malaysian independence in 1957 was eligible for British citizenship.

On seeing this, he went to apply for a British Overseas Citizenship, which would later grant him a clear path to Indefinite Leave to Remain status.

However, he was advised by his solicitor that the Home Office would not accept his application unless he renounced his Malaysian citizenship.

In a bid to stay in the country lawfully, Jack went to the High Commission and renounced his Malaysian citizenship.

His decade-long nightmare began there.

He was officially made stateless.

He commented: “Under my British Overseas Citizenship I do not have any rights – in particular the right to stay in the UK.

“I'm considered undocumented, but cannot be sent back to Malaysia because I’ll just be sent straight back here.”

Jack is currently being financially supported by his group of friends

He is aware that he cannot rely on them forever.

Jack has turned to volunteering to give him a sense of purpose and to give back to the community.

He gets his meals from the local food bank that he volunteers at.

“I’m highly educated, I can bring a lot to this country and contribute to the economy, I just wish that was being considered.

“I hope that this will be resolved in the not-so-distant future. It’s been a long 10 years,” he exclaimed.

Jack said it's very "frustrating and depressing" that his life is on hold due to his legal status

Credit: Thilipen Rave Kumar, Pexels

Credit: Thilipen Rave Kumar, Pexels

Looking forward

Munya Radzi at Regularise, a migrant founded grassroots collective said: “We come across many undocumented people who have lived in the UK for five or ten, or more years, and there is no question that these are members of British society.

“They continue to contribute and participate in society every day but are forced to live on the margins, and in the shadows due to the real dangers of being detained and forcibly removed from the UK.

“With people needing to work in order to provide for themselves and their families, this puts undocumented people in positions where they are at a much higher risk of destitution as well as the increased risks of exploitation by unscrupulous landlords and employers, and, especially for undocumented women, domestic abuse from partners.”

"It is imperative that the UK government takes a positive step to regularise these migrants by granting them status and a safer path to citizenship, as it will save the lives and livelihoods of many who are suffering right now." #regularise@BorisJohnsonhttps://t.co/948Ax4wZl0

— Regularise (@RegulariseUK) May 21, 2020

The Home Office when approached said: “Overstaying is against the law, unnecessarily costs the taxpayer money, and is unfair on law-abiding migrants who come to the UK through the legal channels.

“Those with no right to be in the UK should return home.

“We expect people to leave the country voluntarily but, where they do not, Immigration Enforcement will seek to enforce their departure.”

Some names have been changed to protect identities*

Donate to The Joint Council for The Welfare of Immigrants here.