Breaking point

The UK's real problem with immigration

On the morning of 16 June 2016, Nigel Farage posed for photographs, standing in front of a poster displaying a long line of Syrian refugees crossing the Croatia-Slovenia border.

Overlaid were two words in red block capitals:

BREAKING POINT

And underneath: The EU has failed us all. We must break free of the EU and take back control of our borders.

The billboard was paraded through the streets of London, and widely condemned later that day by politicians from across the spectrum. George Osbourne called it "disgusting and vile", saying it had "echoes" of 1930s Nazi propaganda.

On the left: an actual Nazi propaganda film

— Johnny Marr (@Johnny_Marr) June 16, 2016

On the right: Nigel Farage, today pic.twitter.com/bSOK9veIBI

Exactly one week later Britain voted to leave the European Union.

It was no secret that pro-Leave politicians had placed the topic of immigration front and centre of their campaign. The fear of an uncontrolled mass influx of migrants struck a chord with vast swathes of the population. Even now, with official control restored, Farage and his supporters still have a battle to fight.

EXCLUSIVE FOOTAGE OF BEACH LANDING BY MIGRANTS

— Nigel Farage (@Nigel_Farage) August 6, 2020

Shocking invasion on the Kent Coast taken this morning. pic.twitter.com/iuzAF0Uxz4

There is no doubt the Channel crossings are both dangerous and exploitative. They pose a serious ethical question to all of us, regardless of our politics.

And the Home Secretary, Priti Patel, announced her answer last month. Any person arriving in a small boat seeking asylum would be flown to Rwanda, where their application will be processed.

Former part-time immigration judge and practising solicitor at Refugee Action Kingston Pat Monro believes the proposal is completely unfeasible.

She said: "If if it does take place, it will totally transform the face of refugees in this country.

"Many people take the view that it is in breach of international law, and there are legal challenges being put together as we speak.

"Leave aside the legalities of flying someone who's just arrived here 4000 miles to Rwanda, I have no idea whether the machinery exists there for processing significant numbers of asylum claims."

The plan is still in its early stages, but with the new Nationality and Borders Bill receiving Royal Assent on the 28th of April, claiming asylum has already become more problematic.

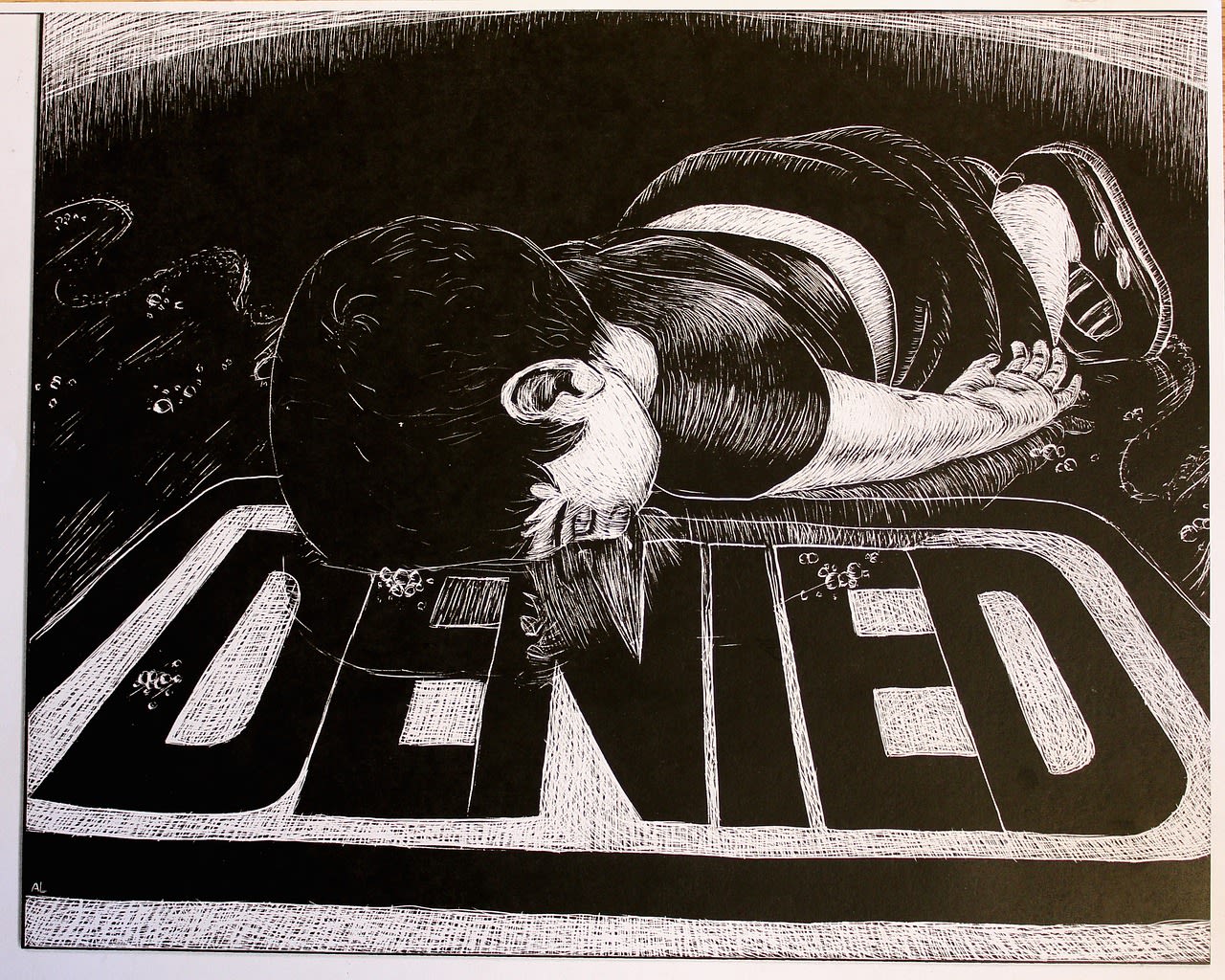

"When I was first sitting as an immigration judge, around the end of the 90s, people were getting decisions fairly rapidly, within the space of months or a year," said Monro.

"Now I have clients who have been waiting three, four years.

"While you're waiting for a decision, you're fearful of the future. You're stuck in the present, unable to work usually for a year.

"If you haven't had a decision within a year then you can make an application for permission to work, but if you're given permission to work, most people can't because you're only permitted to work in certain jobs.

"If you're a brain surgeon, you're fine. But most of our clients don't qualify to work in the shortage occupations on the list that the government produce.

"And the amount of financial support they get from the Home Office is minimal - around £40 a week.

"They want to be occupied and if they're not allowed to work, and they haven't got children to look after it's very difficult for them to find something to pass the time. And if they don't have activities, then they sit and ruminate on what's happened in the past, what may happen in the future.

"I mean it's a terrifying experience for them. And you see the difference when you see someone who's been coming in for a month saying: 'Have you heard? Why haven't you heard? Why can't you make the Home Office give me a decision?'

"And then one day they get a positive decision and their faces transform. They're like a totally different person.

"Of course the challenges don't stop if you're granted refugee status, because you now cannot assume that indefinite leave to remain will be granted after you've been here for five years. That used to be almost automatic.

"The [planned] law basically says that the only way to come here and claim international protection will be if you come through a recognised resettlement program, which doesn't exist at the moment. Resettlement programs are wonderful, but historically they have not resettled an enormous number of people."

Out of 6.6 million Syrian refugees, just over 20,000 were resettled in the UK over four years on such schemes. Last year a total of almost 40,000 people came here to claim refugee status.

Under the recently passed legislation, if you enter without permission, you face four years' imprisonment or being flown to Rwanda.

The idea is it will act as a deterrent to people smugglers, but Monro is extremely doubtful it will prove effective.

"They're not going to stop. Of course, I think we would all like to stop people being exploited and facing great dangers crossing the water or getting into lorries, but people are desperate. And when people are desperate to flee persecution, they will face danger in order to get to safety.

"I don't believe for a minute this new legislation is going to stop that. It will be even more dangerous, the journey and the unknown at the end of it - Are they going to be prosecuted? Are they going to fill the prisons? But they won't stop coming. They won't stop coming."

So what is the solution?

"The resettlement programs absolutely should be supported, but there needs to be far more of them. I heard this morning the Prime Minister is talking about cancelling 90,000 civil servants in order to save money. That's immensely short sighted.

"The delays in the appeal system are appalling. There aren't enough judges and administrative staff to process the appeals.

"What our clients want is to get working legally, pay taxes, settle down and be integrated into society. But at the moment so many of them are horrendously stuck."

The Home Office has been approached for comment.

First featured image: Nigel Farage speaking at the 2018 Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) in National Harbor, Maryland - Gage Skidmore https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/legalcode

Second featured image: Home Secretary Priti Patel speaks at the G6 - Number 10 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/legalcode

Third featured image: Syrian and Iraqi refugees arrive from Turkey to Skala Sykamias, Lesbos island, Greece - Ggia https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/legalcode

Maria's story

'Maria' requested to remain anonymous for her own safety. For this reason her true identity has been obscured.

Until very recently, Maria was one such person, caught in limbo while she waited for permission to work from the Home Office.

As a teenager Maria came to the UK in 2015 from a central European country. It had been arranged by her family that she would marry a man she'd never met upon arrival.

She was given some money and drivers were paid to ensure her safe passage.

"And when I came here, I just escaped. I didn't want to meet this guy. I just ran away," said Maria.

"It was the first time I'd been out of my country. I'd never been by myself. I went to a different city, then I met someone from my country and I asked him: 'Please, I'm supposed to meet a friend, but I don't want to meet him. Please, can you help me?' For a long time he was the one who supported me.

"I lived on a houseboat. I was really afraid. I needed to be somewhere where no one could find me. I couldn't tell my parents because they would be mad at me for running away. I just pretended to them that I was with the guy."

Maria stayed in hiding for around five years on the houseboat. During that time she became pregnant and gave birth to a son. Eventually, her parents realised the truth.

"They threatened to kill me. When they found out about my son, that his father was not the man I was supposed to marry, they threatened to 'throw the child', you know? They didn't care anymore. They cared for what? Just for reputation.

"They believe you should be a good wife. It doesn't matter if you've been beaten up or they treat you like rubbish, you just have to zip it and say that's your duty. That wasn't for me. I never saw that.

"If people don't understand you, let them. It doesn't matter who they are. If it's your family, it doesn't matter. Why should I do what they want when I say that's not good for me? We should do what's best for us.

"That's why I've decided to leave the past and to fight. I will never give up. I have a little son and he deserves a life. After all these years I've been living a horrible, difficult life. No, I don't want this for my son. I don't want him to see me always down.

"When I was pregnant I thought of killing myself sometimes. I was thinking: 'What am I doing in this world? What security is there for my son? I don't have any papers. I don't have anything. And if my parents find out what's going on they will kill me.' I was thinking of jumping in the river. I knew I couldn't swim. At least I will be food for the fish."

Maria was too scared to reach out for help in case the authorities sent her back to her family. Then one day someone recommended she visit Refugee Action Kingston.

"I was going to some English classes, because there was nothing else, just activities with my son and I really wanted to learn English. A lady said: 'Have you heard about Refugee Action Kingston? They might give you some options that might help you.' I was so afraid to talk because I thought: 'How can I trust them? I don't know who they are.' She said: 'No, they help people like you in your situation.'

"She came with me and we met the lovely Johara. We didn't know if they would take our case straight away. But she said: 'Okay, don't worry. I'll take it.' I was shocked.

"I didn't know at all that it existed. After five years, I just found it out. I didn't know what to do. I'd never heard about an asylum seeker. I didn't know what it was."

This was over two years ago and finally, in January of this year, she received the news that she had been granted permission to work in the UK.

"Johara calls me and she says: 'Your papers came. They sent you a letter.' I was getting on the train and I screamed with joy. I couldn't believe it. 'It's not me,' I said 'Can you double check if it's my name, maybe they...?' 'It's you!' she said."

Maria found work as a nursery pre-school assistant almost immediately and relocated to a flat, where she was also supported to register to study for further qualifications at college.

"It's amazing. The people are amazing. I love it. I just love working, because I've been here seven years without working, nothing. Do you know how tiring it is, to be like that?

"When I came here to this county I felt like a bird without wings. But now I received my papers, I'm working, my son's in nursery, I feel like a bird with wings. I can fly. I can be capable of looking after my son. Do you know how good it feels to work, to buy food for your family, to pay your own rent, to pay your own bills, with no one helping you?"

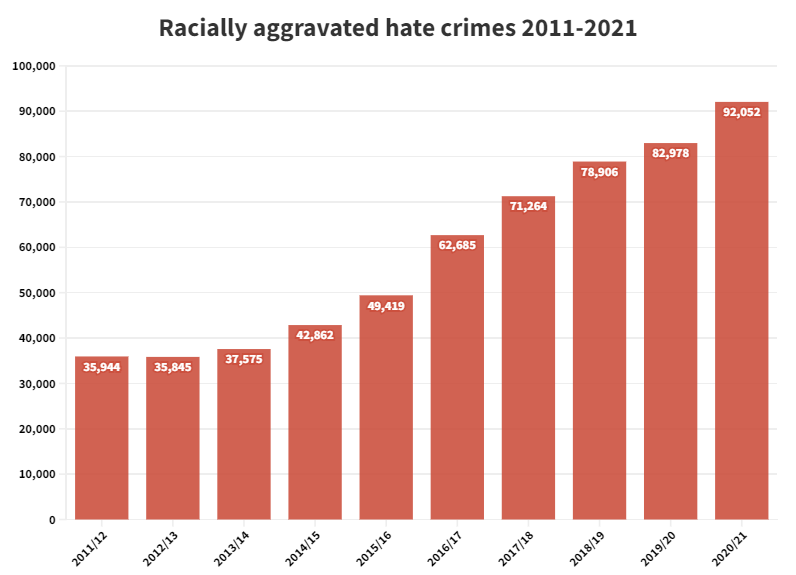

Unfortunately, for many migrants like Maria, dealing with overt racism has become a daily struggle. In the last decade the number of reported hate crimes in the UK has more than doubled.

"When people see you as an asylum seeker, do you know how bad they look? They look you in the eye like you are under their foot. Some people treat you like you're not a human being, but we're all the same.

"When I was living on the boat people were thinking I was a gypsy woman, treating me so badly. Like a lady was passing by and asked if that was my garden. She was pushing the fence and being so aggressive. I thought she was going to push me and my son in the river. I was so afraid. I just called the police.

"They have a good life themselves. And they don't have a clue what it means. They don't know me. They don't know what I'm going through. But it hurts."

In another incident a woman started filming Maria, threatening to call the police because her dog was barking.

"She started saying: 'You people living here. Go back to where you came from.' All these things hurt you. All I want is people not to bother me. Just leave me alone. I don't bother you.

"I don't let them do it anymore. No one can put me down. I'm strong enough. I don't want my son to grow up with this. I don't want people to swear at me when I'm with my son who's three years old, because he does understand. Who are they to tell me off? What for?"

Houseboat on the Thames - Amandajm https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/legalcode

Houseboat on the Thames - Amandajm https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/legalcode

Source: Gov.UK Hate crime statistics 2011-2021

Source: Gov.UK Hate crime statistics 2011-2021

A lifelong struggle

Discrimination quickly becomes a daily reality for refugees, no matter where they end up. But for some the reality is worse than for others.

Mo works as an Integration Support Worker and, like many of the volunteers at RAK, came to the UK as a refugee himself. He arrived in 2019 following the Sudanese Revolution where thousands of, mainly young, civilians protested against the failing authoritarian government.

The Khartoum massacre in June 2019 saw over 120 unarmed protestors shot dead, more than 650 injured and 70 raped.

"Everyone either left, were put in jail or are in complete poverty. That's my friends who are all very educated people, my family and the people I knew. It's just sad... It's just really sad."

Mo found integrating into British society easier than most, completing his Master's degree and quickly making friends thanks to studying English at undergraduate level in Sudan.

But that hasn't stopped him feeling frustrated at the way some treat him, especially in light of the overwhelming UK support for those fleeing the conflict in Ukraine.

"I'd say the biggest challenge I face, and I've faced it until today and I think I'll never stop facing it, is that I am a refugee. And I will never ever be looked at as anything other than that, to be quite honest. This process is a very long one and it's a lifelong process. Even if you get the passport, it will still be a lifelong process, in terms of integration, in terms of how the community sees you and how you see the community, in terms of your identity.

"No matter how eloquent I sound, no matter how hard I work, to some people I'll always be a refugee. And there are always negative connotations with this word, and that's what makes me angry.

"I mean, the doors are quite open for people from Ukraine, and that's a great thing. Even though in the UK we didn't open many doors compared with other European countries, humanitarianism cannot be politicized. No refugee is better than another.

"I saw a very famous news reel and they said: 'This is happening in Europe and they are people like us, with blue eyes and blonde hair.' Human beings are human beings at the end of the day."

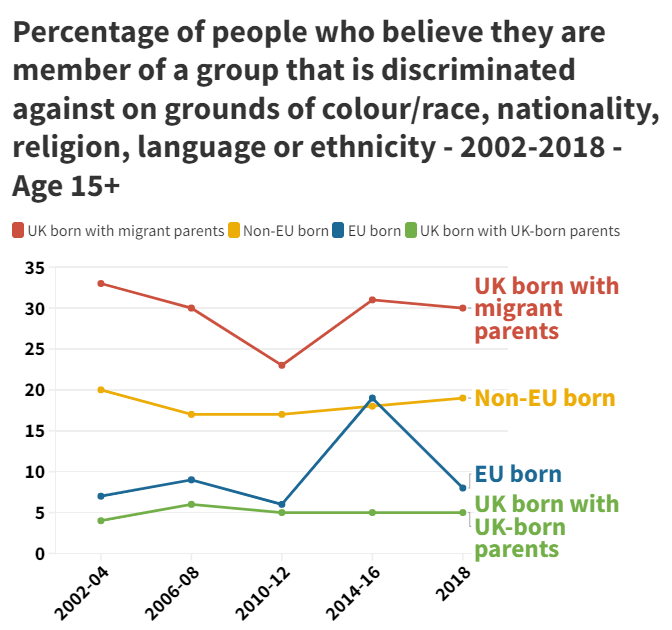

A briefing from the Migration Observatory showed that non-EU migrants (19%) were more than twice as likely to describe themselves as members of a group that faces discrimination as migrants from the EU (8%) - though the latter saw a temporary spike around the time of the Brexit referendum.

Mariña Fernández-Reino, Migration Observatory researcher and quantitative sociologist, explained.

Link to the briefing discussed: migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/…in-the-uk/

"It has always been the case in the UK. Visible minorities - people who can be identified as belonging to an ethnic minority by the majority of the population - are usually among the most discriminated minorities. So for example, black minorities are usually amongst the most discriminated in Western countries, not only in the UK."

And, perhaps surprisingly, second generation migrants (32%) were twice as likely to perceive discrimination than migrants themselves (16%) in 2016-18. Clearly a discrepancy between perception and objective discrimination plays a role in this.

"It's something that happens in all countries in general. When you're born in a country, and most people that are children of migrants are UK citizens themselves, they expect to be treated as equal. Sometimes migrants are aware somehow of their lesser status and are more likely to accept that they are not being treated equally.

"For children of migrants, who are born here, go to school here, whose peers are British, it's normal that they are more sensitive. Obviously it has an impact on your wellbeing because they're feeling British and they spend all their life here. That creates a lot of frustration and it affects people in the long term."

So for Mo and Maria, unless something drastically changes, not only will they be dealing with discrimination all their lives, their children will face the same struggles too, if not worse.

As Mo said: "The funny thing is that there are no negative connotations when it comes to the word 'expat.' It's a privilege to be an expat and a curse to be a refugee."

If you or someone you know live in Kingston and are seeking asylum or have refugee status and would like help, then contact Refugee Action Kingston: https://www.refugeeactionkingston.org.uk/contact-us

Alternatively, if you would like to support the work of this great charity then you can donate https://www.refugeeactionkingston.org.uk/donate

Or volunteer: https://www.refugeeactionkingston.org.uk/volunteer

Syrian activist and singer Mohammad Abu Hajar at a Sudanese revolution solidarity march in Germany - Hossam el-Hamalawy https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/legalcode

Syrian activist and singer Mohammad Abu Hajar at a Sudanese revolution solidarity march in Germany - Hossam el-Hamalawy https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/legalcode

Source: Migration Observatory analysis of the European Social Survey 2002-2018 for Great Britain

Source: Migration Observatory analysis of the European Social Survey 2002-2018 for Great Britain