Britain's last stand

What would London's final protest have said about us?

On Saturday, thousands filled London’s streets. They gathered in peaceful protest because they knew this could be their last chance to be “disruptive”, to be a “nuisance”, to hold hands under a unified cause.

From suffragettes to miners, at Peterloo or Westminster, serious bids for change in Britain have rarely been fanned into flame without the spark of civil disobedience.

But as the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts (PCSC) Bill prepared to be pushed through the House of Lords, protestors knew all this could change.

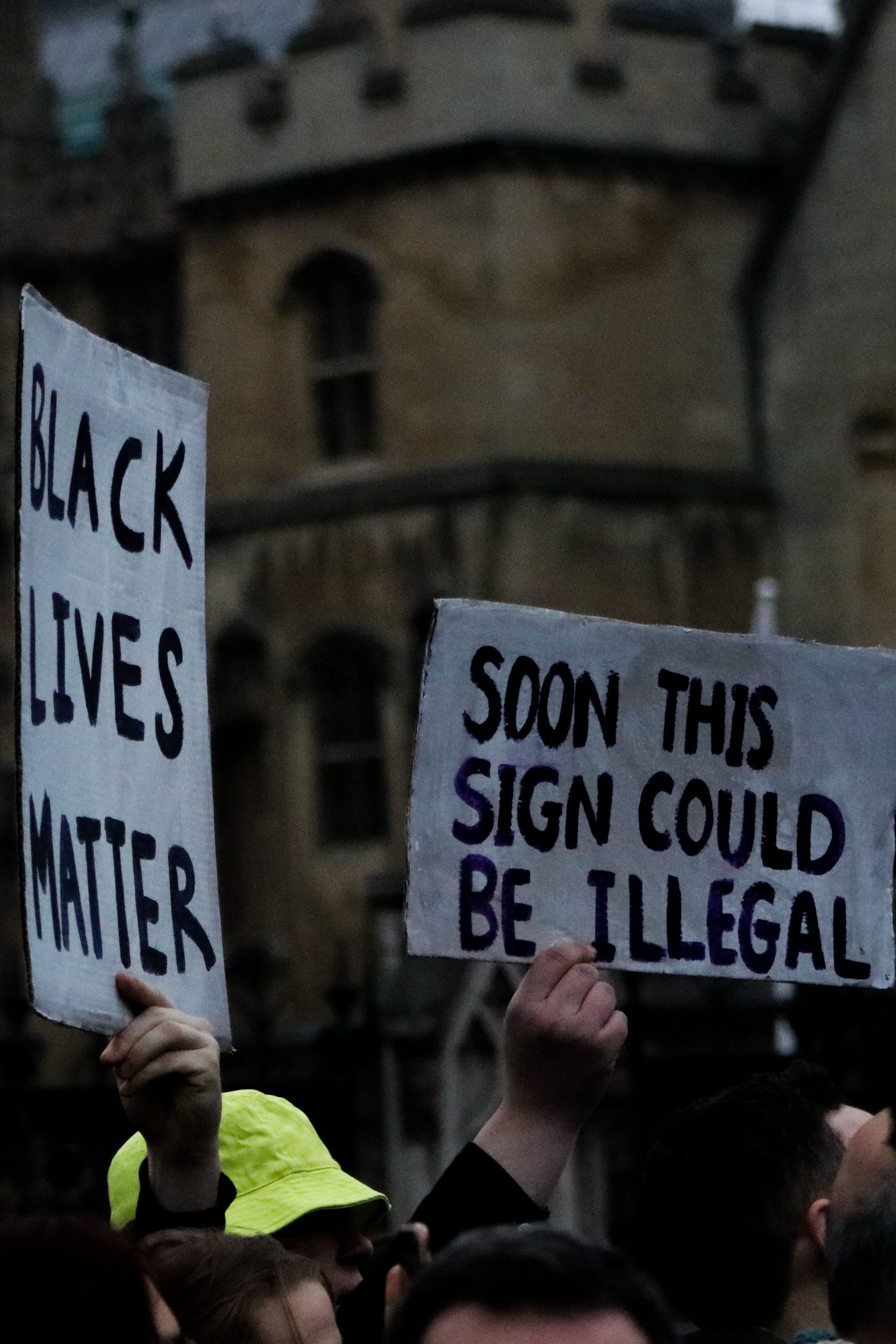

The bill threatened an end to organised dissent, with police given the authority to ban protests deemed “seriously disruptive”, even if this meant being too noisy.

In preventing “serious disruption” or a “public nuisance”, cops would not only have the authority to ban protests, but could stop and search anyone they think may be carrying “banned” items – such as banners or leaflets.

This would be true “whether or not the constable has any grounds for suspecting that the person … is carrying a prohibited object”.

The bill also had the potential to effectively criminalise Gypsy, Roma and Traveller people, banning people from stopping on public and private land without permission.

The bill was defeated three days after the protest in the Lords, with peers voting 261 votes to 166 against police powers. A further vote backed an amendment to strip the power to impose conditions on protests on noise grounds.

However, on Saturday, with protest itself at risk, protestors across the country joined London and marched - to be able to march in the future.

As one banner said, it was all very “meta”.

We were looking at the culmination of a country's protesting culture. Its final stand.

So what does that protest highlight about us?

Looking down the barrel of an end to dissent, what was prioritised, and how did they act?

Youth

Speaking to SWLondoner after the march, ex Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn said: “Youth culture is about hope, it’s about opportunity, about art, about music, about discovery, about learning and about inclusion.

“The more young people I interact with, the more I meet, the more hopeful they make me.”

This was key to the march – young people were not just present, but placed at the forefront. They were handed the mic, literally, as a flux of protestors cascaded down the strand.

Leading from the front, there was an eagerness for empowerment – to be heard in their own right and for others to respond.

Amy Rose, 19, lives in London and led chants across the protest route.

She said: “Young voices are the voices of the future. We’re the ones who are going to be making the difference.

“We have to get out on the streets and we have to make action and change, because the other generations have put us into the position, and nothing is changing.”

This was repeated by Chip, a 20 year old student at Brunel University.

She said: “The only way that we can push for climate action and for social change is through protest, and that’s the way that the public are most empowered.

“It’s really scary the rights that we are going to have taken away from us if this goes through.”

It is easy to dismiss these as the words of young activists, quick to blame those that have come before them.

But in an open letter signed by 315 psychiatrists and psychologists condemning the Policing Bill in regards to mental health, their view is concurred.

The letter states: “We cannot think of better measures to disempower and socially isolate young people who are already suffering the devastating mental health consequences of disrupted education and prohibited social contact imposed by the pandemic.”

The letter continues to highlight perceived hypocrisy as the government “claims to be prioritising children’s mental health and wellbeing”.

This sense of betrayal with those in power is supported by a recent poll from the Lancet.

Almost 60% of 16-25 year olds across the world were very or extremely worried about climate change. This fear correlates to them seeing an inadequate government response, and feelings of betrayal.

This was also picked up by older protestors.

Angela, 76, who joined the protest as a part of XR Grandparents and Elders, said: “We did it. Unwittingly – we didn’t mean to – but we’re responsible for the problem.

“We care. We care about our children and grandchildren. It’s not just an issue for young people, it’s up to us to put right what went so badly wrong.”

Young people were at the forefront of this issue.

Not just in person or in voice, but in the sensibilities of the people who marched. It looked to the future, acknowledging that there were fights ahead and empowering the young to contest it.

Diversity

Protests across the UK have drawn attention as products of white middle class “crusties”. But Insulate Britain were far from the minds of those in London.

When they held traffic to a standstill at the junction of the Strand and Waterloo Bridge, they posed with halted buses, finding safety in numbers.

Many explained that this was a result of race – without the “white privilege” to be able to glue yourself to the road and not suffer consequences, they are limited to dance, music and peaceful disobedience.

Three things that, under the PCSC, would be classed as “public nuisance” and “disturbance”.

Robin, an Extinction Rebellion Activist who plays an agogô at protests, says if the bill passed she could face going to prison for a year by playing music.

She said: “As a person of colour I want to show my dissent.

"We have to show dissent, and I can’t do that in a way that a lot of Extinction Rebellion people do, which is go out and be arrested, stick their hands to things and whatever.

“Do you know what would happen to me if I get done? Black people already have to do more applications to get a job.

“If I get a criminal record for playing in the band – which is my only way of showing protest – how else am I supposed to say anything?”

According to a study by experts based in the University of Oxford's Centre for Social Investigation, people from minority ethnic backgrounds going for jobs would have to send 60% more applications before being successful.

This is virtually unchanged from figures recorded in the 1960s.

For a protest like Insulate Britain’s, Robin says, you “need a s**t load of privilege.”

She continued: “This form of protest it so important for me, because I can’t do that Insulate Britain rubbish. I think that I would be treated far worse than other activists who do that.”

She describes XR’s Samba band as vitally important – for her it is responsible for allowing people of colour to join as activists.

Patsy Stevenson, the woman famously pictured held down by police at Sarah Everard’s Clapham Common Vigil, echoed this view of a white bubble in protest at her later speech.

She audibly choked back sobs as she told the crowd: “Before the vigil I was a student, I wasn’t an activist, and because of that when I had interviews I would say: “We need to direct it away from the police."

“I didn’t know what I was talking about. I was in a white privilege bubble, I didn’t know what was going on and I didn’t listen to the women around me who had been telling me for years that this had been happening.”

Patsy Stevenson speaks to protestors in Parliament Square

Patsy Stevenson speaks to protestors in Parliament Square

Policing

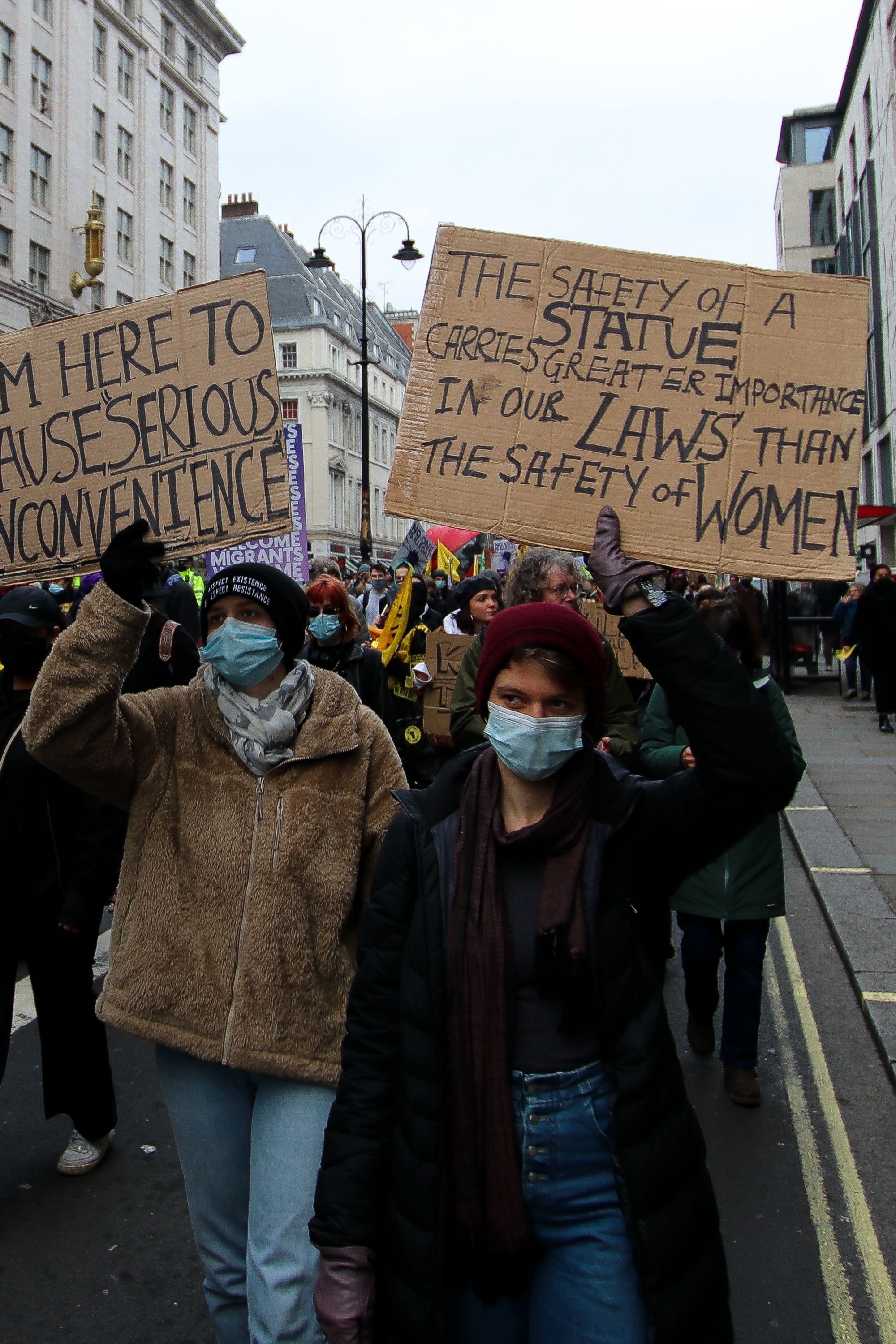

The memory of Sarah Everard still courses like a dirge through London.

Placards against police impress themselves on the background of every image, and distrust of the force is a cornerstone of each march.

Patsy Stevenson continued: “How are you hiring more police on our streets when you havn't sorted out the ones that are already in power, abusing their power.”

Many from the crowd went on to attend the vigil for teacher Aisling Murphy that same evening.

The 23-year-old primary teacher was killed while out running in Ireland, barely three months after Wayne Couzens was sentenced to life imprisonment.

However, the police kept a respectful distance. A respectful presence, diplomatically trying to keep peace.

One of the blue-jacketed Police Liaison Officers, followed around by a arrowed placard, saying “Don’t talk to them” stood calmly for photos from the press.

He observed “My best friend is back!” when the protestor returned from a break.

Emma Mamo, the Head of Workplace Wellbeing at metal health charity Mind, recently told policing newspaper Police Oracle that: “Even before the pandemic, we know that police officers were far more likely than the general population to experience mental health issues such as stress, anxiety and depression.

“Coronavirus has made the roles of policing staff even more demanding.”

Mind research shows 66% of police staff feel their mental health has deteriorated as a result of the pandemic – this cannot be helped as they are faced with standing calm in the face of such a pressure of ill feeling.

In one instance, a young female officer echoed words familiar to anyone who has worked in a bar at last orders.

“I am just doing my job,” she told a protestor screaming inches from her masked face.

She had been alongside a male police officer, who had asked how long they planned to stay seated on the Strand.

If this had been the end of protest, police would have concluded it with dignity. They looked in the face of pressure calmly and played out their role in the civil disobedience.

The police may find themselves as the end of protest, but as London took its final stand, it stood aside and let them march.

Politics

Now we know the Lords have voted down the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill, it is easy to look at the protest through rose tinted glasses.

At the time protestors marched with the visceral urgency of people faced with the choice of fight or flight.

The bill was necessarily a political issue, with protestors marching the day after Labour peers committed to voting against it.

Natalie Bennet is a Green Party peer who lobbied against the bill in the House of Lords.

Speaking to crowds in the shadow of Westminster, she said: “I’ve two things to say. First of all, protest is not a crime.

“And secondly, we are not going to allow them to take away our agency, our power.

“We are going to take to the streets, keep taking to the streets, keep making noise, and we’re going to Kill the Bill and make the UK a democracy.”

Emma Goodwin, an Environment Agency employee, travelled from Essex in a personal capacity to join the protest.

She said: “Being able to get out on the streets, make my voice heard, has been really important to me over the last couple of years.

“One of the ways I have coped with some of the climate grief and anger and rage that I have felt at the government is to get out and make my voice heard, and that is what is being threatened by this bill.”

Goodwin was a part of a group that held hands throughout the march – something the bill’s provisions would effectively ban.

She continued: “We do need meaningful protest. We don’t need a bill that is going to make that illegal, and stifle that cornerstone of our democracy.”

This sentiment was concurred by Jeremy Corbyn, as he succeeded Natalie Bennett in front of crowded activists.

He said: “If the right to protest is restricted, if you have to seek police permission to do anything, where does that lead to?

“It leads to every protest becoming a conflict about having the protest rather than what the protest is about.

“It effectively disempowers us all, puts us all on the back foot and puts us all in a totally defensive mode. So we end up endlessly defending things instead of demanding things.”

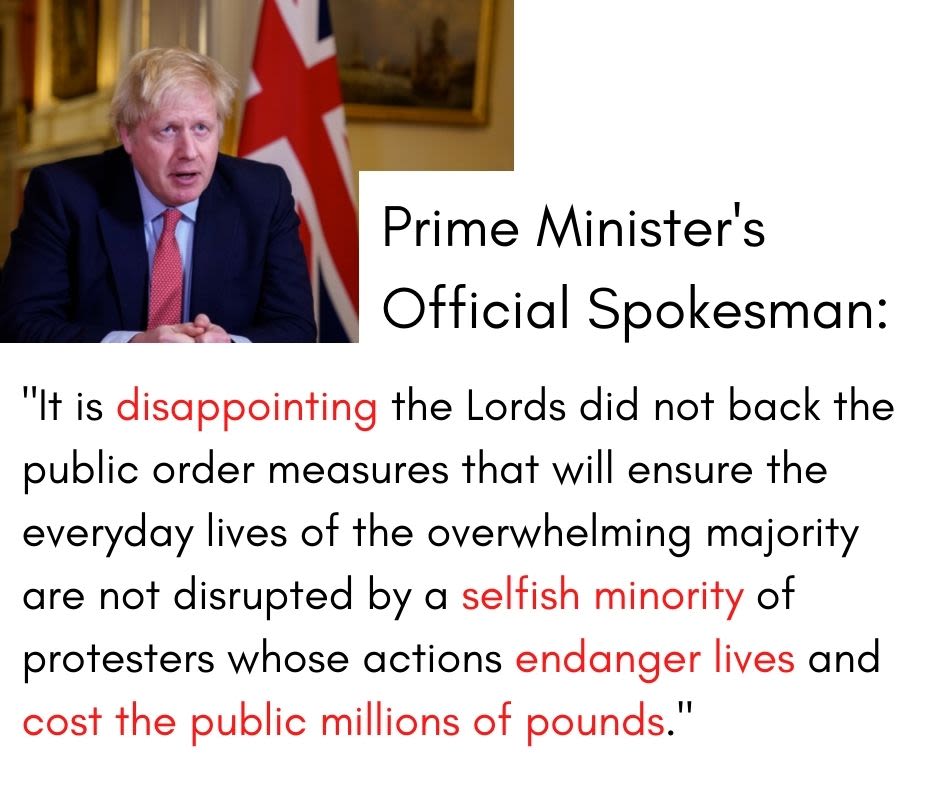

The Home Office commented: “We will always champion the right to protest peacefully and this bill in no way changes that.

“We have seen some of the most self-defeating and dangerous protests in recent years with people gluing themselves to motorways, causing serious disruption to the law-abiding majority across the country and tearing police away from communities that need them most.

“That’s why our Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill is so necessary – it gives police the power to proactively prevent this kind of chaos before it ensues, and focuses on a selfish minority of relentless reoffenders.”

This is unlikely to be accepted by Kill the Bill activists.

Their view of the government is not just suspicious; believing to be received in hostility, they return this scorn with venom.

Isolated from those in control, they join with radical thinkers like Corbyn and Bennett to fight a government they believe attack their rights.

Green Party peer Natalie Bennett speaks to protestors in Parliament Square

Green Party peer Natalie Bennett speaks to protestors in Parliament Square

Last night Labour blocked the Government from introducing new measures to stop Insulate Britain & XR bringing our country to a standstill.

— Priti Patel (@pritipatel) January 18, 2022

Once again Labour’s actions are proving they are not on the side of the law-abiding majority - instead choosing to defend vandals and thugs.

Last night, Labour and the Lib Dems voted against our Policing Bill siding with Insulate Britain and Extinction Rebellion protestors who blocked highways, ambulances and workplaces.

— Oliver Dowden (@OliverDowden) January 18, 2022

They voted to make it to harder for the British people to get on with their lives pic.twitter.com/4elfrs4pHv

Last night, Labour & the Lib Dems shockingly joined forces in parliament to BLOCK our plans to stop protestors glueing themselves to roads & thereby cause misery to thousands of motorists just trying to earn a living, take loved ones to hospital and get on with their lives!

— Rt Hon Grant Shapps MP (@grantshapps) January 18, 2022

While the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill may have been defeated in the House of Lords, this does not mean there is an end to the bill.

It is simply the start of a process of going back and forth between the Lords and the Commons, with the government still fighting for its proposals.

But the vote has swung - with Conservatives limited by their more slim majority in the Lords and opposition parties whipped against them, their bid to pass the bill is facing a revolt.

Furthermore, the House of Lords also voted to make misogyny a hate crime in England and Wales and backed, by 238 votes to 171, a Liberal Democrat amendment to remove the power to impose conditions on protests on noise grounds.

And so, while this protest may not be London's final stand, it is enlightening to see how we act when we face that prospect.

As a culmination of Britain's protesting culture, it brought the country's youth to the forefront, recognised diversity as a key and pertinent issue, was fuelled by anger towards policing and fought side by side with political allies.

While defending the rights of Insulate Britain's "crusties", protestors were not necessarily fighting for the same cause or sympathetic with the people themselves.

They fought for their rights peacefully, pragmatically and powerfully by taking to the streets and petitioning for support.

As politicians were quick to note, protest is not just a right to be protected.

It works.

House of Commons Voting Breakdown

House of Lords Voting Breakdown