CANCELLED

How the far right stole free speech

When hundreds wrote to Priyamvada Gopal to threaten her with racial and sexual violence, it was because they felt that she was racist.

The Cambridge academic and commentator on race and British Empire had been doxed — her contact details and purported address leaked online. Laminated posters of her face and name, alongside others bearing white supremacist slogans, had appeared throughout the city.

Online rumours, impossible to verify, reported that threatening individuals were searching to find her home.

“At one point the hate-mail was coming in at the rate of five or six emails a minute,” Professor Gopal said. “They were arriving from different countries, and some of them from anonymous addresses. It was then that I realised how well organised this was. There was a lot being put into play.”

Gopal’s preferred collective noun for the emails is ‘sewage.’ The metaphor sticks. Numerous though they were, the messages were obedient both in their odiousness and in their desire to be channeled downhill, to the lowest possible point of discourse.

Some lurched indecisively between braying slurs and issuing reminders of her debt to western moral and intellectual superiority. Some warned her of the vengeful white crusade her writing would one day invoke. Some entertained themselves by graphically conjuring every conceivable affront to her personhood: deportation, torture, mutilation, rape, murder, the murder of her loved ones and her students — by lynching them or by burning them alive.

Others swore to inflict these punishments upon her personally. They reminded her that the Cambridgeshire Constabulary, who had visited her home to check on her welfare, could only protect her for so long.

The most unanticipated element to these messages, though, was the thing they said to her more than anything else.

They told her that she was a racist.

In fact, some even called her a Nazi.

She hated white people, they said, and the messengers would do all that was necessary to defend themselves from a vicious assault upon their ancestry, their identities and their civilisation.

And in online circles, and among some members of the press, their perspective has been gaining ground.

To understand why this was happening is to also understand how the current invocation of one of the greatest principles of liberal democracy — an individual’s right to free speech — may have lost its liberatory potential.

And how its transformation into a reductionist binary has allowed it to be used convincingly by those who wish to destroy it, and against those who need it now more than ever.

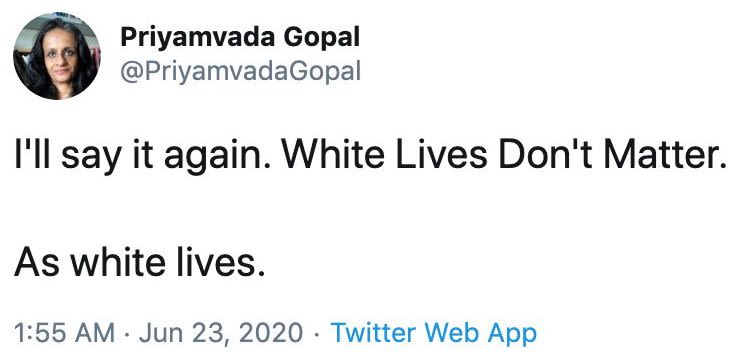

For Professor Gopal, it all started with one tweet.

It may not be over, but it is safe to write that the summer of 2020 was a grotesque carnival of global suffering. And of revolt.

The brutal killing of an unarmed black man by a US police officer had ignited the largest demonstrations against racism, inequality and police brutality since the civil rights movement.

Protests, projected against the tattered economic and social backdrop of a global pandemic, had spread around the world.

They spoke of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, Elijah McClain and Tony McDade.

And Rashan Charles, Mark Duggan, Sarah Reed, Stephen Lawrence and Belly Mujinga.

These are to name only a few.

They are still speaking.

As the pandemic gripped the UK tighter than anywhere else in Europe, an already uneasy national consciousness spiralled into a deep fever.

Hundreds of thousands had burst onto the streets of over 150 British towns and cities.

On June 20th a mentally-ill Libyan man fatally stabbed three men in a park in Reading. Immediately afterwards, Ash Sarkar, a prominent left-wing journalist and activist of Bengali heritage, was ensnared by the mania of a far-right conspiracy theory which asserted she had secretly colluded in bringing about the men’s deaths.

A few hours before the killings, she had posted a picture of herself with an ice lolly in a London park. The conspiracy theorists alleged that the three orange emojis in the photo's caption corresponded to the lives of the soon to be murdered men, and they demanded vengeance.

Thousands may have held command of the streets — for one week, possibly two — but those who were trying to move the conversation further were facing abusive opposition online.

It was a forewarning of what was fast approaching Professor Gopal.

On June 22nd, in an eerily empty Etihad stadium, players from Manchester City and Burnley football clubs took the knee in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement.

An airplane flew overhead. Behind it trailed a banner that read, “WHITE LIVES MATTER BURNLEY.”

It was in this context that Gopal wrote her tweet.

When she said that white lives don’t matter as white lives, she was making a point, provocative though it was, that a Professor of colonial and postcolonial literature was well positioned to make: in a racialised order where whiteness sits at the top, and ‘white’ people only think of themselves as ‘white’ in relation to ‘otherised’, subjugated ‘black’ and 'brown' populations fighting to be freed, ‘white lives matter’ is an assertion of supremacy.

As she has written in a Guardian comment piece: “White lives already matter more than others so to keep proclaiming they matter is to add excess value to them, tilting us dangerously into white supremacy. This doesn’t mean that all white people in western societies are materially well-off or don’t experience hardship, but that they don’t do so by virtue of the fact that they are white. Black lives remain undervalued and in order for us to get to the desirable point where all lives (really do) matter, they must first achieve parity by mattering. It’s not really that hard to understand unless you choose not to.”

Gopal wrote her tweet and sent it, thinking nothing more of it.

Until the sewage arrived at her door.

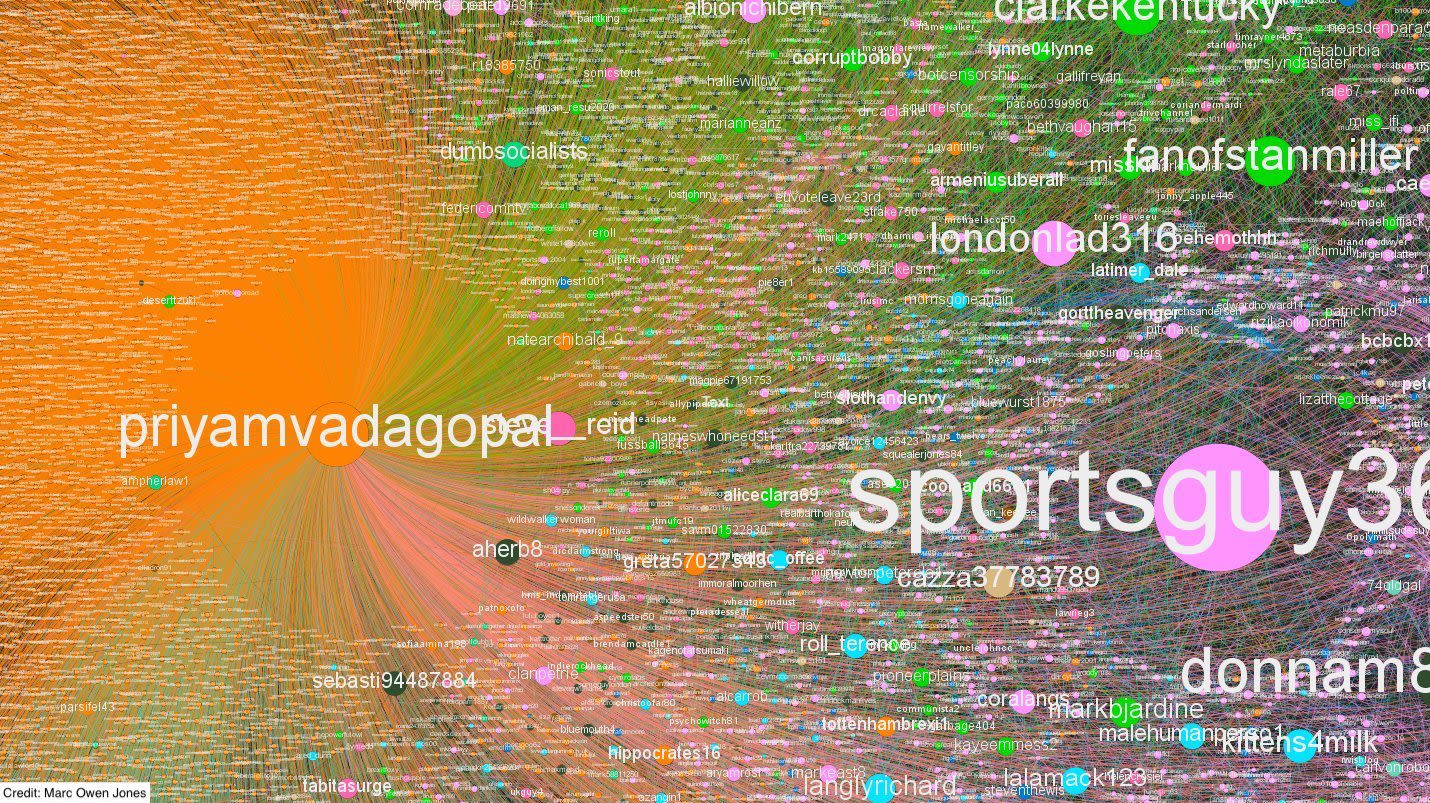

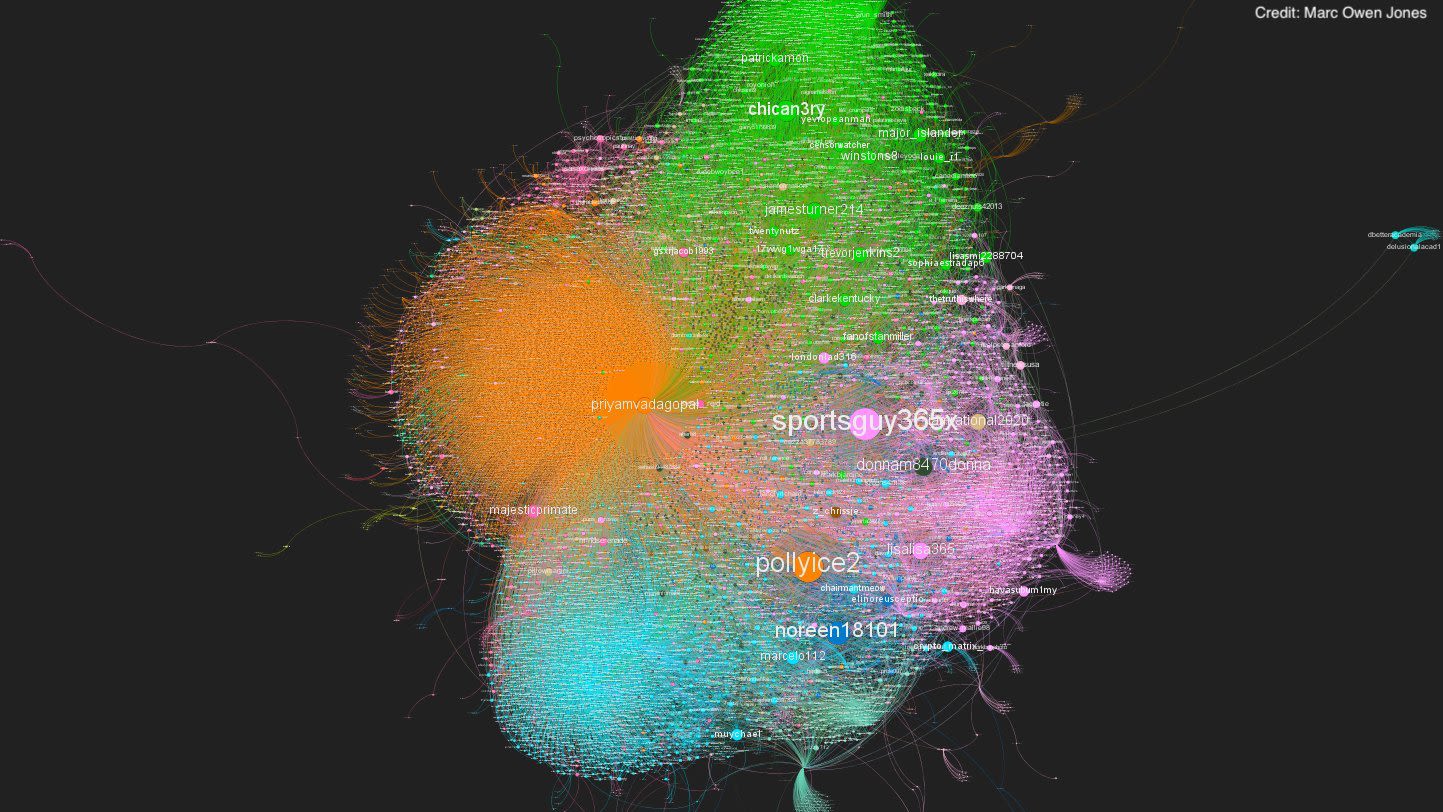

[Thread] Wow, this is all the Twitter traffic involving @PriyamvadaGopal over the past two days. Around 35000 interactions from around 15000 unique accounts. Obviously many of support, but much of it racist bile pic.twitter.com/yQ4oa3peZA

— Marc Owen Jones (@marcowenjones) June 25, 2020

Just one day into her tweet's existence, and the data shows that Professor Gopal had become the centre of an enormous, growing web of abusive twitter traffic.

"The charges of ‘she is the real racist, she needs to be fired,’ were in full flow by the night of the 24th,” Gopal said. “What they were doing is picking up the discourse of shutting down racism and using it to shut down anti-racist discussion.”

By the morning of the 25th June, Gopal had been temporarily suspended from both Facebook and Twitter.

Complaints spilled in to Cambridge University and to Cambridgeshire Constabulary, urging for her sacking and arrest. As if unsure that her tweet alone would provide enough kindling, screenshots of a doctored version without the second, qualifying sentence were speedily distributed.

This practice reached an absurd climax when a post from a fake twitter account, mimicking Gopal’s, entered into wide circulation urging readers to "carry out a resolute offensive against the whites." The quote, it turned out, was actually one of Stalin’s. The false attribution was discovered and debunked, but not before it received a share from the Daily Mail columnist Sarah Vine, which she later apologised for and deleted.

According to an analysis of the twitter storm by Marc Owen Jones, an Assistant Professor at Hamad Bin Khalifa University, the clearest commonalty shared by the twitter accounts sending abuse to Priyamvada Gopal were the pro-Brexit and pro-Trump positions in their bios.

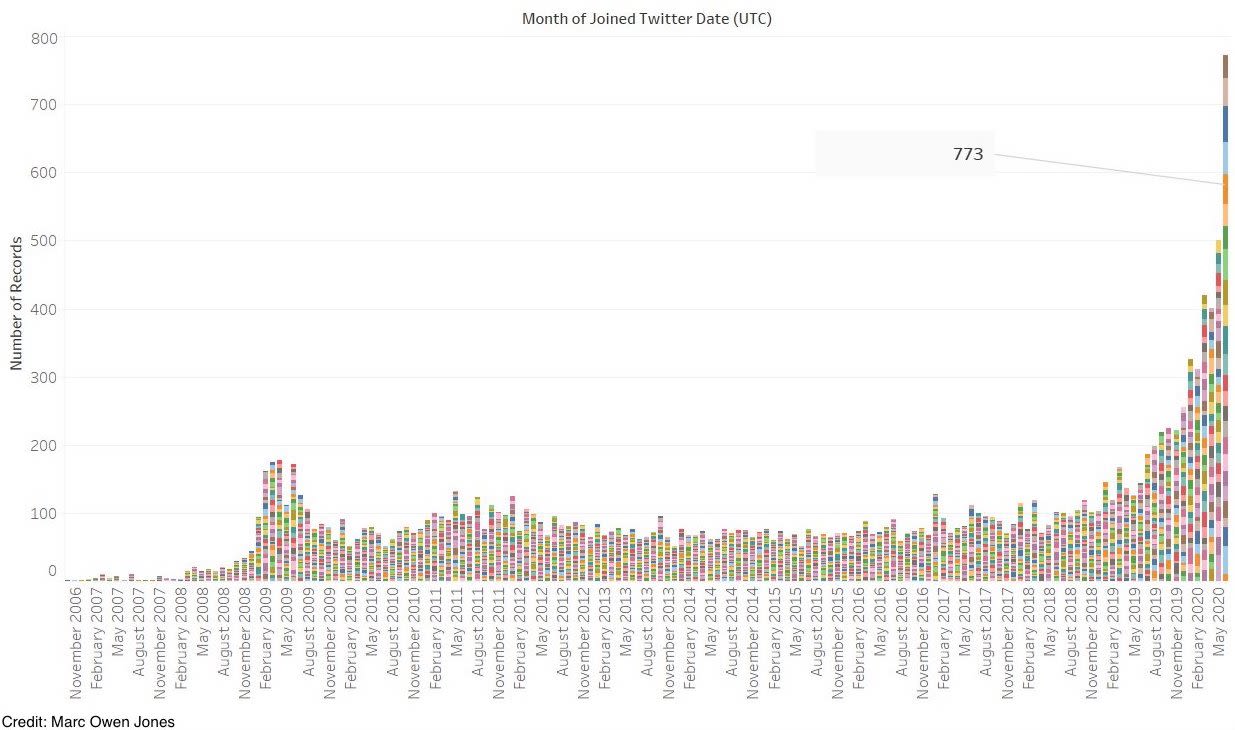

More insidiously, the pile-on was amplified by a large influx of new accounts to the site.

“Often this can be an indicator of trolls, bots, or just people enthused to join twitter due to specific events. Haven't seen a spike like this for a while though,” he tweeted.

In the two days following her tweet, Jones recorded around 35,000 interactions with Gopal’s twitter account, stemming from 15,000 unique profiles.

“This activity was a manifest attempt to pressure me into silence,” Gopal said. “I underestimated how deeply convinced they were, or how deeply they wanted to convince other people, that white people were the real victims. My tweet gave them what they saw at first as a smoking gun.

"But it wasn’t what they were hoping to find.”

For Professor Gavan Titley, a lecturer in media studies at Maynooth University, concocted scandals of this kind, intended to obstruct and foreclose discussions on race brought forward by already marginalised voices, have a long history. And it is a history intimately connected with the restriction of their speech.

Rather than grappling with whether Gopal’s point on whiteness was true, her attackers preferred to silence discussion by calling her a racist for how she phrased it.

It was the spectacle, and not its content, that mattered.

Another variation on the theme is to pass over the broader implications of a racially meaningful event in favour of a narrow debate over whether it can be called ‘racist’ or not.

“Something will happen and people will say ‘yes, if that was racism that would be really bad, but let’s all talk about whether its racism or not,’” Titley said. “It has the effect of closing down political spaces and ending certain kinds of possibility. If we think a thing can be achieved politically by discussing it publicly, it tends to shut that process down.”

This tendency, to discuss racism as an event that should be vigorously debated in order to categorise it as ‘racism’ or ‘not racism’, is one aspect of what Titley has called the ‘debatability’ of racism. In the hands of a talented journalist or presenter it quickly becomes a route for transforming difficult and complex discussions about social structures into riotously amusing bun-fights over who, or what, gets to be called racist.

It has also become a way for more nuanced exchanges to be ended before they can begin.

“There are ideological entrepreneurs who are very adept at finding a slightly exaggerated tweet, holding it up and then saying: ‘This is the sort of craziness that passes for anti-racism these days. Anti-racism has gone too far, and it’s now part of the problem,’” Titley said.

“Historically that’s something you can see going right back to the 50s, through the 60s, 70s and 80s. Nowadays, they prosper even more through social media, because everything can be turned into a spectacle, a scandal."

In order to be categorisable enough to debate, racism is also implicitly understood to be a thing that everyone can recognise, rather than something that is always changing. It is ‘frozen’ in time — an idealogical hangover from an abandoned past filled with fantastical beasts: Nazis, Caribbean slaveowners, and practitioners of South African apartheid.

But Professor Titley argues that if we refuse to recognise racism as a constantly shifting set of relations, varying over time and unique to every society, we condemn ourselves to perpetually adding fresh examples to its ugly history.

“We can take Luke De Noronha’s work on Windrush as a perfect study of this,” he said. “As a result of their changing relationship with the British state, black Britons of Jamaican heritage were turned into Jamaicans, and made to be deportable. This wasn’t a consequence of a continuity of racism against Jamaicans in Britain, it was produced by an apparatus which identified them as a risky population that needed to be ‘managed.’"

But perhaps the most disquieting effect of the prevailing attitude that racism always can, and should, be debated, is the way in which it has allowed the far-right to claim that they are being ‘cancelled’ if minorities refuse to dutifully engage with them. Even if the topic of the debate is said minorities’ right to exist.

In some quarters, students’ refusals to enter into debates of this kind have been collected alongside the disorienting social effects that the expansion and digitisation of public life have created (and the subsequent erosion between private and public, citizen and employee) and given a name: ‘cancel culture.’

The currency of this expression gained even more value when 153 prominent public figures, including J. K. Rowling, Steven Pinker, Gloria Steinem, Noam Chomsky, Martin Amis, Salman Rushdie and Margaret Atwood, signed an open letter published in Harper’s Magazine on July 7th arguing that stifled free speech was creating an “intolerant climate” within society.

Though it wasn’t named directly, the media quickly attributed their appeal to a rejection of cancel culture.

Vaguely defined though it may be, most of those who argue of the threat posed by cancelling are clear enough in pinning the blame for illiberal shifts in public discourse not on profound and rapid technological change, sustained economic fallout or the continued erosion of minority rights, but on what they perceive as growing orthodoxies among students, academics and users of online forums.

A particular focus of ire is No Platforming — attempts made by students to disrupt, or ban outright, the appearances of far-right figures at campus talks and debates.

The strategy began in the UK in the late 70s as a means of resisting attempts by the fascist National Front to gain a foothold at universities.

It has since expanded to cover all forms of recognised hate speech, including sexism, homophobia and transphobia.

Dr Evan Smith, who is a research fellow in history at Flinders University in Adelaide, and has recently published a history of No Platforming, said: “It makes sense that there’s a lot more attention being paid to No Platforming nowadays, but I also think that’s because of social media and the global rise of the far right. The media landscape is way wider now, so there are so many more avenues for people to talk about it.

“I think we’re used to viewing universities as reified spaces that are different from the rest of society. People protest against politicians in all sorts of places, and a lot of the time when people say that No Platforming has taken place, they actually mean that there was a protest at the event. First and foremost universities should be safe for students and safe for research — and that involves keeping people free from prejudice and harassment. That doesn’t mean we can’t discuss controversial or dangerous ideas. I teach classes on terrorism, fascism, the Khmer Rouge, and I discuss them critically. But they’re not held up as ideas worthy of debate.”

But some still feel that debates for and against the merits of racism are the best way to eradicate it.

Take this comment made by the comedian Tom Walker, best known for playing satirical news correspondent Johnathan Pie, as he appeared on Channel 4’s Ways to Change the World programme:

“Freedom of speech is an immovable right for horrible people as well as nice people. If you’re a horrible person, if you’re a racist for example, I want to hear it. As long as you’re not inciting hatred, as long as you’re not inciting violence. If your opinion is that the colour of your skin makes you superior to me because of the colour of my skin, you should be able to say it because then I can argue against you. If it’s illegal for you to say it, it bubbles up. So that’s just the general level of what surely freedom of speech should be.”

Stirring though this appeal may be, for Professor Titley it refuses to take into account the uneven social and economic terrain on which debate is usually set out. The signatories of the Harper’s letter, for example, are some of the most well-known and well-respected public intellectuals, writers, academics and artists on both sides of the Atlantic. Their best-selling work is never out of print. They speak at packed events around the world.

Similarly, the academics and columnists who decry the rise of university cancel culture do so in well-paid pieces published in widely respected national newspapers. A student from a racialised or politically marginalised background simply does not have the same means with which to engage in an evenly-matched debate.

“The conceit is that all ideas are equal, unique expressions of the conscience of the speaker. When you’ve got somebody standing up to give the same old script, and black students decide they’re not sitting around for another debate on debunked theories of IQ — that they know what it’s about and they’re not going to treat it with respect — the response to that will then be: ‘Well you have to have the debate.’” Titley said. “There’s a sense here that the world is born anew every day, as if ideas and speakers don’t have history. That’s amplified by social media. You can always find a venue for these ideas and then say: ‘Debate me. Oh you won’t? You must be scared of engaging with my ideas, you must be trying to shut down my free speech.’"

“The far right have become very aware of the weaknesses of these notions, and they’ve exploited them very effectively. They can then claim to take on the mantle of defending civilisation and its principles — which they don’t believe in — against woke students. Of course there are massive excesses in student movements, but when have there not been? What I find much more disturbing is that there are editors at the New York Times who are happy for their columnists to write a column every two weeks about student politics. That’s far more disturbing for me than the fact that students in a college somewhere have got too zealous about the names of cocktails in the student canteen. What’s the investment in making that into a pressing civilisational issue?”

The unerring focus on cancel culture and race in the chilling of free speech becomes harder to understand in light of the many other substantive, growing threats to the principle's practice.

Nothing could be more damaging to social media platforms than the proposed amendment of Section 230 of the 1996 US Communications Decency Act, for instance, which currently protects websites from legal liability for what their users post. As of the time of writing, both Republicans and Democrats are united in their intent to seek changes to the clause. Republicans say their ideas are being censored, while Democrats claim there is too much hatred and election meddling online.

Meanwhile, Chinese developed AI surveillance technology is steadily being exported to authoritarian regimes around the world.

And two weeks after the Harper’s letter J.K. Rowling, arguably the most famous signatory, leaned on the powerful system of UK defamation law to force an apology from children’s news outlet The Day. It had published an article which implied that she was transphobic.

For Gopal, who survived her attempted cancelling and was promoted to a full Professorship by Cambridge University, free speech is best understood in opposition to the one thing which has always attempted to throttle it: organised power.

“Colonial subjects have actually never seen the free speech side of empire. Empire was all about censorship and sedition laws, and presented itself from the very beginning of its bureaucratic presence as an anti-free speech entity. So it’s always been very bizarre for colonial subjects to be told that Britain represented freedom and democracy, because they never saw that side,” she said.

“What we learn from the history of anti-colonialism — and the fact that so many people underwent trials for sedition, for violating press censorship and bans on gatherings, demonstrations and public speaking — is that free speech is only rendered meaningful if it is enacted through kicking against the norm, through an act of courage. It manifestly doesn’t mean punching downwards at already marginalised groups. Free speech only gathers meaning if it is used to challenge power.”