COURTS IN CRISIS

Last year saw a record backlog of criminal cases and courts literally falling down.

South West Londoner spoke to the barristers who have had enough to find out why.

“The system is in total collapse and I think it is important the public knows about it,”

Claire Howell, who has been a criminal barrister for almost 20 years, told South West Londoner.

Claire, who is based at Drystone Chambers, London, says that she has worked on cases which have taken as long as four years to go to trial, despite involving extremely serious crimes.

Indictable only offences, which are the most serious crimes such as murder, manslaughter and rape, have seen the mean number of days between the offence and trial completion more than double, from 262 days to 570, since 2011.

Last year saw a record backlog of criminal cases in the Crown Courts, with 60,692 cases received and not completed by the end of June according to the National Audit Office (NAO).

Meanwhile, over half of courts have been closed down, and many of those left standing are in a state of disrepair.

With barristers, judges and court staff all saying that the system is at, if not beyond “breaking point”, what is causing the crisis and what, if anything, can solve it?

How is the backlog affecting those caught up in the system?

The victims

Statistics show that victims in the most serious crimes are having to wait on average over one and a half years between the crime and their trial completing.

Delaying hearings for as long as this can prolong the trauma experienced by victims of serious crimes.

It also means that witnesses and other concerned parties can forget details of the crime, bringing doubt into their testimonies and jeopardising the standard of justice which is delivered.

"When they come to court, sometimes 3 or 4 years later, and are cross-examined, they say well it was years ago, I can't remember," Claire said.

Today in howling at the moon just seen a young woman who reported her rape at the age of 15, her case may be heard by the end of this year, she is now 19. 4 YEARS!!!! SHE WAS A CHILD.

— Jess Phillips MP (@jessphillips) September 24, 2021

Catherine Atkinson, Chair of the Society of Labour Lawyers, said that she believed long waiting times could be putting victims off coming forward.

"What is obviously already a tough time in their lives is being made worse," she told South West Londoner.

Claire describes the pain of having to inform her clients, often victims of horrific crimes, that their trial is delayed:

The defendants

Chris Matthews, a court reporter with CornwallLive, said he has witnessed countless examples of people escaping crime and moving on with their lives before being taken back to court, sometimes years later.

“One man I know of was caught moving drugs, and has since moved on with his life and put all that behind him.

“He got engaged, got a house, got a really good job and then three years after the offence was hauled back and sent to prison.

“He’s not a danger to society, he’s just an idiot who got in with the wrong crowd and he got three years in prison because they’re coming down quite hard on drug offences at the moment.”

Fair Trial, a charity which campaigns for prisoners’ rights, has highlighted that thousands of defendants are having to wait for trials in prison for months or even years - far longer than the 6 month statutory limit - before being tried.

The lawyers

As Claire highlights in the above audio clip, the news about delays which are severely affecting complainants and defendants, usually has to be delivered to them by their representative barristers.

The emotional toll trials are taking on them is therefore heightened by the backlog, as Claire explained: “It's a huge emotional pressure.”

“In the past a barrister would get paid a certain amount and out of that you pay your rent to chambers, you have to pay your own pension because you are self employed, you don't get any holidays and you would have to factor all of that in, but at least you would be able to take a bit of a break in between horrible cases.

“But now you just go completely back to back, you finish one case - I just finished a case involving horrible allegations involving a child - and I'll go straight into another one.”

@BarristerSecret @DominicRaab We have today had a sex trial adjourned for 12 months because there wasn’t a prosecutor available in the ENTIRE country to do it. #thelawisbroken

— Martin Scarborough (@MartinScarboro4) December 13, 2021

Natasha Isaac, a family barrister at 1 Crown Office Row, Brighton, said she was put off joining the criminal bar due to its low pay and high workload, and says she admires those who stay with it despite the huge pressures.

According to officials at the Criminal Bar Association, 22% of junior criminal barristers have left the criminal bar since 2016.

What is causing the backlog?

Has Covid-19 caused the backlog?

In a word, no.

The NAO’s report found that the backlog was already increasing before the pandemic, by as much as 23% in the year leading up to it from 33,290 on 31 March 2019 to 41,045 on 31 March 2020.

However, existing problems in the system have undoubtedly been exacerbated by the pandemic.

Lockdowns severely delayed in-person trials, to the extent that as in the NHS, ‘Nightingale Courts’ were set up to help ease the backlog.

Natasha Isaac - family barrister at 1 Crown Office Row, Brighton

Natasha Isaac - family barrister at 1 Crown Office Row, Brighton

Video links between court, prisons and lawyers’ offices also became commonplace over the pandemic, with 13,600 cases a week now using them.

Natasha said this has helped to modernise the system, but is not without its problems.

“One positive that has come out of the pandemic is the use of video hearings. But we do have difficulties with it such as which platform to use and how it works, and it would be helpful moving forwards to have some structure in place," she said.

“I know that people are working on it but it has been almost two years now that we have been in this situation and still, pretty much every day I use a video hearing there is an issue with it.”

Many trials are now back in person, and with the virus and restrictions ongoing, adjusting to the new normal is presenting its own issues.

Chris said that prison vans being late means trials are pushed back, which he says has been a problem as long as he’s worked as a court reporter, but that Covid has made the situation even worse.

“The amount of cases that have been listed at 10am and haven’t taken place until later in the day because the prison van is late is huge.”

“I know that some of that is down to Covid because obviously in prison it’s a nightmare. When a prisoner comes into contact with someone who has Covid everyone is sent back to their cells and none of them can come to court."

“There was quite a big waiting list before and then when Covid hit there was four months when there were no jury trials whatsoever so that’s four months of trials that got knocked back.”

Chris said while he has noticed the backlog getting worse in recent years, he thinks this is because he has become more aware of it personally.

He said that well before the pandemic, experienced Circuit Judge Simon Carr was appointed to Truro Crown Court to “deal with the backlog”.

Judge Carr commented in 2019, months before the pandemic began, that the system was “beyond the point of collapse” after one case took two years and nine months to get to court.

Covid has undoubtedly affected the backlog, but as these statistics and testimonies show, it was already piling up long before the pandemic.

Watch below for more on Natasha's views of the backlog, what's causing it and how it might be solved:

Natasha Isaac - Family Barrister, 1 Crown Office Row

Natasha Isaac - Family Barrister, 1 Crown Office Row

Government underfunding

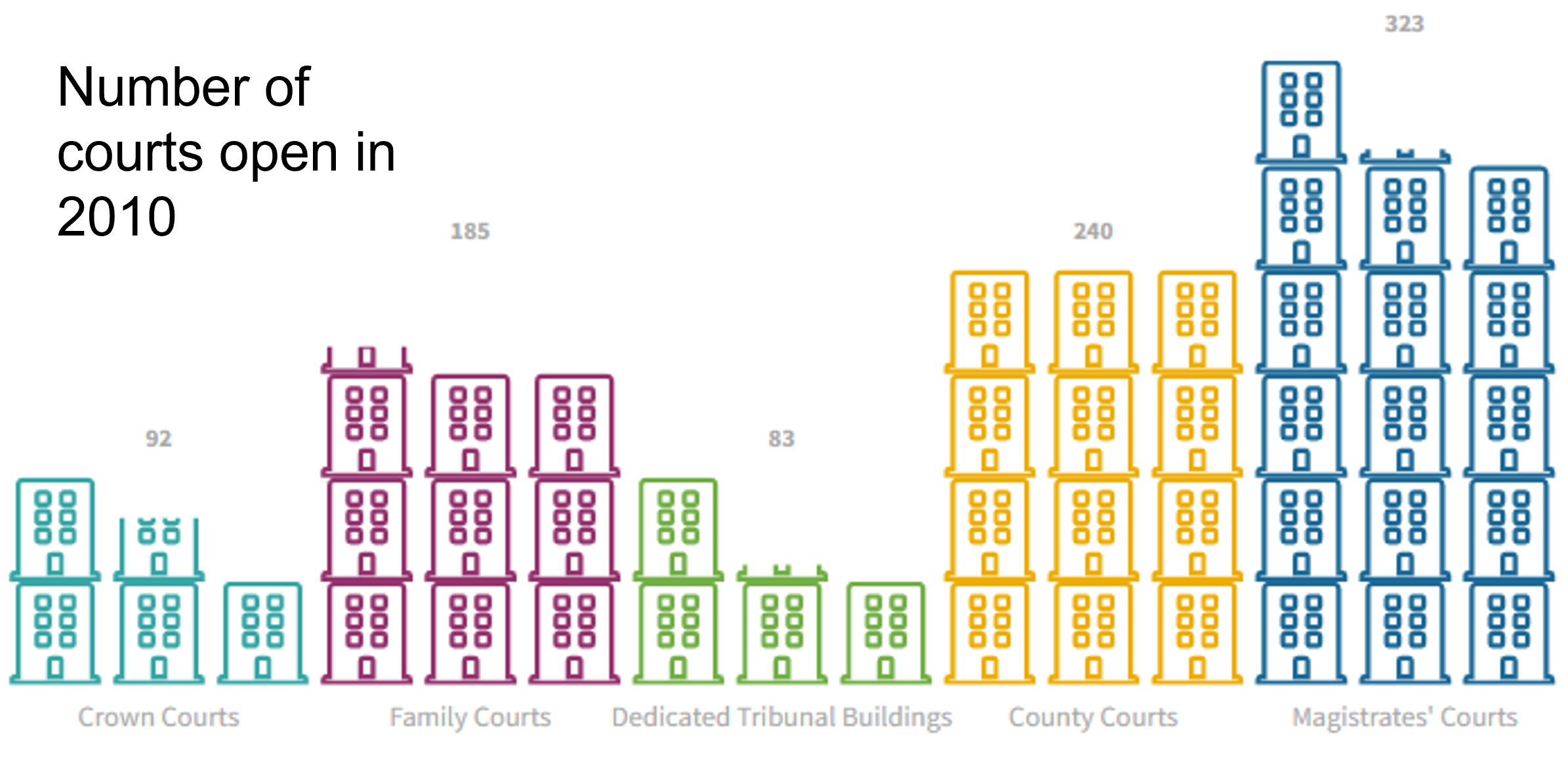

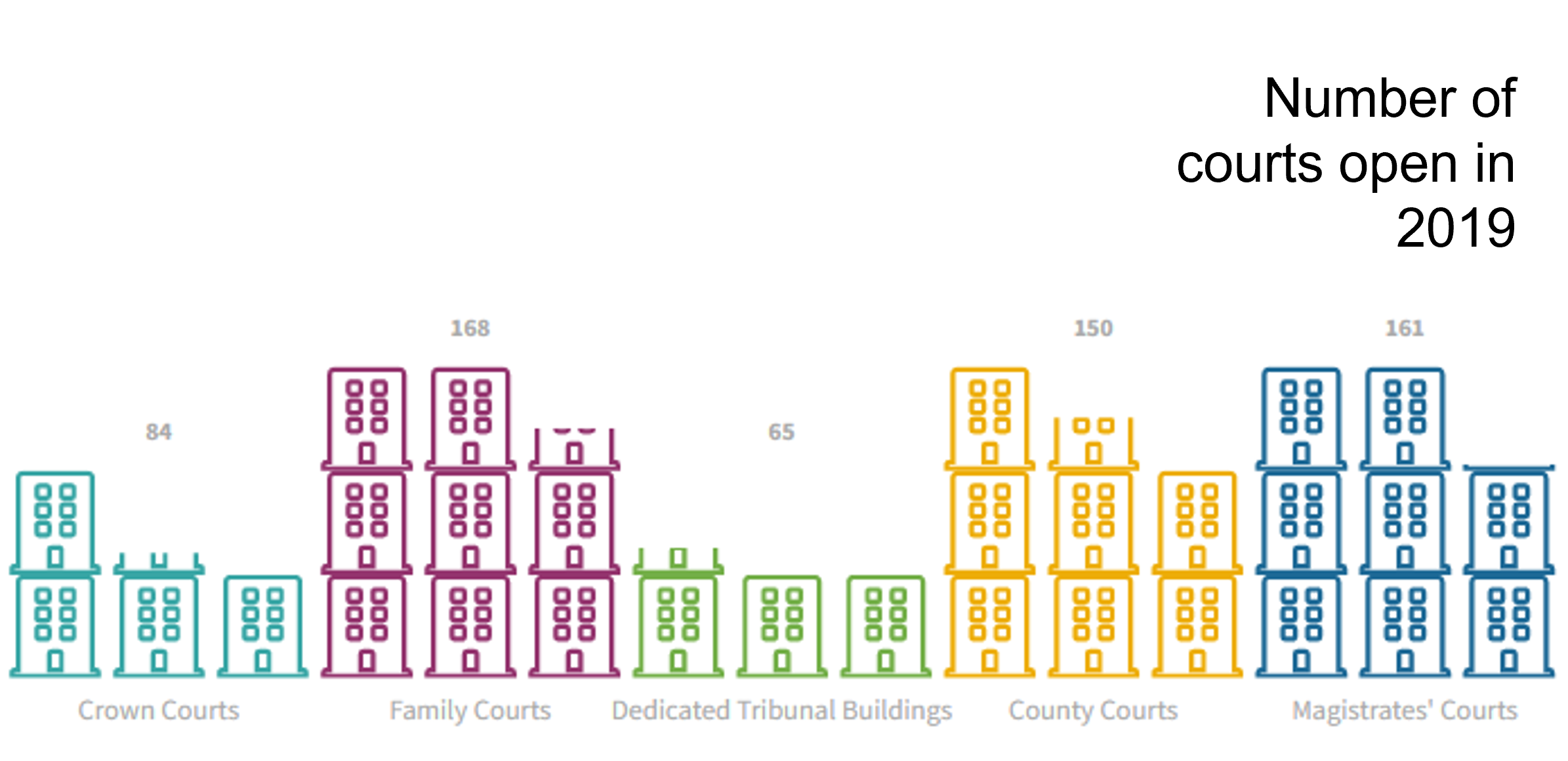

The budget for the Ministry of Justice was cut under austerity and decreased by around 25% between 2010-11 and and 2019-20.

These cuts have resulted in courts closing across the country, less legal aid being made available and a general reduction in court and legal services.

"When the Conservative government came in, in 2010, it felt like the courts and the legal system were safe to cut to the bone and we are seeing the reality and the repercussions of those years of underfunding," Catherine said.

Claire said that she is not criticising the government over the state of the courts because of her personal politics, but because she wants to see improvements in the system.

"I'm not a political person, I don't have any agenda apart from just wanting to do my job," she said.

"I just want my cases to be heard, so that the jury can hear what complainants have to say and make their minds up, because ultimately, the people I represent deserve a trial and on both sides of the divide."

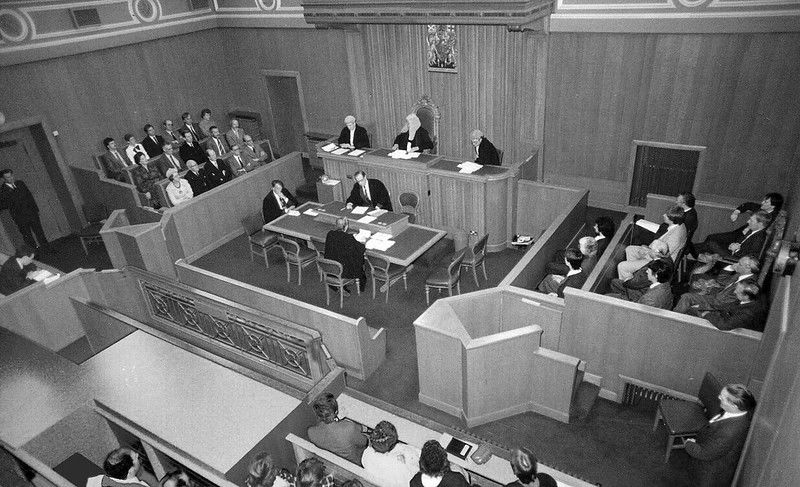

All the barristers who spoke to South West Londoner highlighted the state of disrepair many courts are in as a stark example of underfunding.

The Society of Labour Lawyers recently published photos of some of the damage at Maidstone and Snaresbrook Crown Courts to raise awareness about this disrepair in a 2022 calendar called the Crumbling Criminal Justice Calendar.

Claire Howell - criminal barrister at Drystone Chambers, London

Claire Howell - criminal barrister at Drystone Chambers, London

Listen here to Claire explain her view of the cuts.

The charts below show the number of court closures between 2010 and 2019.

Source: House of Commons Library

Source: House of Commons Library

See the Society of Labour Lawyer's photos below.

"You can't have an efficient system if it's falling down."

Claire describes how she and other barristers had to wait in long queues to see their clients because prison meeting rooms were unusable.

TWO rooms in one crown court’s cells area have not been usable for WEEKS causing huge difficulties and delays as barristers can’t see their clients

— Claire Howell (@claireeshowell) September 3, 2021

Why?

The lightbulb in each room has gone

And the powers that be

cannot agree whose responsibility it is to replace them

💡💡💡

The cost of the works is apparently 2k to re-wire and fit LED lights in two rooms. The cost of delays to trials over five weeks plus is enormous.

— Claire Howell (@claireeshowell) September 19, 2021

It’s such a tiny example but so symptomatic of the state the whole justice system is in.

The lights literally are now going out….

Representatives from the Society for Labour Lawyers presented these pictures of the "crumbling courts" to government ministers and shadow ministers in December 2021.

"How can we have a just society when there are such delays and the system is literally crumbling around us," Catherine told South West Londoner.

She said that the state of the courts is making it even more difficult for those who work in them, as well as those who have to attend them, to get through cases.

She said this is just increasing delays and adding to the backlog.

The Ministry of Justice (MoJ) did not respond when asked about this issue.

Reduction in sitting days

All of those who spoke to South West Londoner highlighted a reduction in the number of sitting days, meaning the number of days judges are expected to hear cases a year, as a key issue.

Chris said of his experience at Truro Crown Court: “When I started court reporting there were two courts open every week and now, because they only have so many sitting days, there’s only one court on the go, which means they’re getting through half the work effectively."

The number of days is allocated each year by the MoJ in line with what they expect to be the number of cases coming to court each year.

The NAO found that 16% fewer sitting days were allocated in 2019-20 than in 2018-19, despite the MoJ acknowledging that there could be a long-term increase in cases coming to court.

In December, Antonia Romeo, Permanent Secretary of the MoJ, told MPs on the public accounts committee that the courts backlog is “not necessarily” the result of government spending cuts.

Romeo explained that sitting days were set in line with the “all time low” of outstanding cases recorded in 2018-19, and that they did not anticipate the rise in cases.

The MoJ has since increased sitting days in response to the backlog.

Is inefficiency causing the backlog?

Maidstone Crown Court

Maidstone Crown Court

While the NAO’s survey and many barristers argue that a lack of funding is the key factor in causing the backlog, inefficient systems and lack of staff has also played a part in delaying trials.

Claire described a case she was involved in at Kingston Crown Court failing to go ahead: “This case was originally fixed, it was made a floater at the last minute as other cases overran and there are not enough courtrooms or judges at the moment.”

The Court responded: “The case was not able to go ahead as it was a floating trial and all other trials were effective, so we had no court to place it into; this is not uncommon for floating trials which are always listed to back other trials.”

They explained that the trial was made a “floater”, meaning it was delayed for a number of weeks with no specific date or court allocated to it, because they were unable to source an interpreter.

A spokesperson for Kingston Crown Court told South West Londoner: “The case was not able to go ahead as it was a floating trial and all other trials were effective, so we had no court to place it into; this is not uncommon for floating trials which are always listed to back other trials.

“The company who supplies our interpreters were unable to source one on this occasion; again this is not unusual.”

Claire said in response to this: “If the court is regularly not being supplied with interpreters when they have been booked and that’s “not unusual” as the court says, that’s a pretty scandalous waste of money and time as even if we had a courtroom our case wouldn’t have started without one.”

“The realities of the management in the system are horrendous.”

The Institute for Government said in its review of the Autumn Budget that "in theory" there is enough money to address the backlog but that lack of staff is making it more difficult in practice.

Is there a solution?

The government says it has increased funding to cope with the backlog, with the 2021 Autumn budget pledging the "largest funding increase for more than a decade".

As Natasha said in the video: “I hope that the backlog will reduce but I really can’t comment on how likely it is or not, the government has its hands tied up in lots of other very important matters.

“It is possible to fix the problems, I don’t think that they are things which can’t be solved and I hope that people will turn their minds to them.”

But Claire is not convinced. "The solution is investment but the government doesn't want to invest."

"I am really afraid, I don't have much hope for the future."

She said that the government is acting too slowly and that in the meantime victims and defendants, as well as their representatives, are suffering.

The MoJ announced a series of new measures on 18th January which it says will help to tackle the backlog.

These include more video hearings, Nightingale Courts and allowing serious offences to be heard in Magistrates Courts.

The MoJ said: "The impact of these measures is already being seen.

"The number of outstanding cases has dropped by around 70,000 in the Magistrates’ Court since its peak in July 2020, while the caseload in Crown Court is starting to come down."

Image credits: 1. Gordon Johnson, Pixabay, 2. Sarah-Rose, Flickr, 3. Natasha Isaac, 1 Crown Office Row, 4. Claire Howell, 5-7. Society of Labour Lawyers, 8. Mike McBey, Flickr, 9. Michael D. Beckwith, Flickr, 10. Society of Labour Lawyers, 11. Rae Allen, Flickr.