Doing better: Decolonising education to build anti-racist schools

The case for 'decolonise the curriculum'

The coronavirus pandemic exposed numerous systemic issues including an insidious epidemic that has plagued the United Kingdom for decades.

Following months of Black Lives Matter protests in the wake of George Floyd’s death, thousands of UK students have shared their personal experiences of racism in schools, and initiated campaigns to tackle discrimination through education.

Department of Education school census data published on August 13th showed that 4904 pupils were excluded for racist bullying in England between 2018-2019, up from 4329 in the previous academic year and the highest on record since 2006.

Racial harassment was also deemed commonplace and grossly overlooked in UK universities after an inquiry by the Equality and Human Rights Commission last year.

Now, testimonies on Instagram and Twitter by current and former secondary school pupils nationwide are revealing similar tropes of structural racism, unchecked racial stereotyping and ethnocentric curricula in UK state education.

Students are mobilising for change with petitions and letters to public officials calling for an overhaul of the English national curriculum and demanding solutions that go beyond words of solidarity.

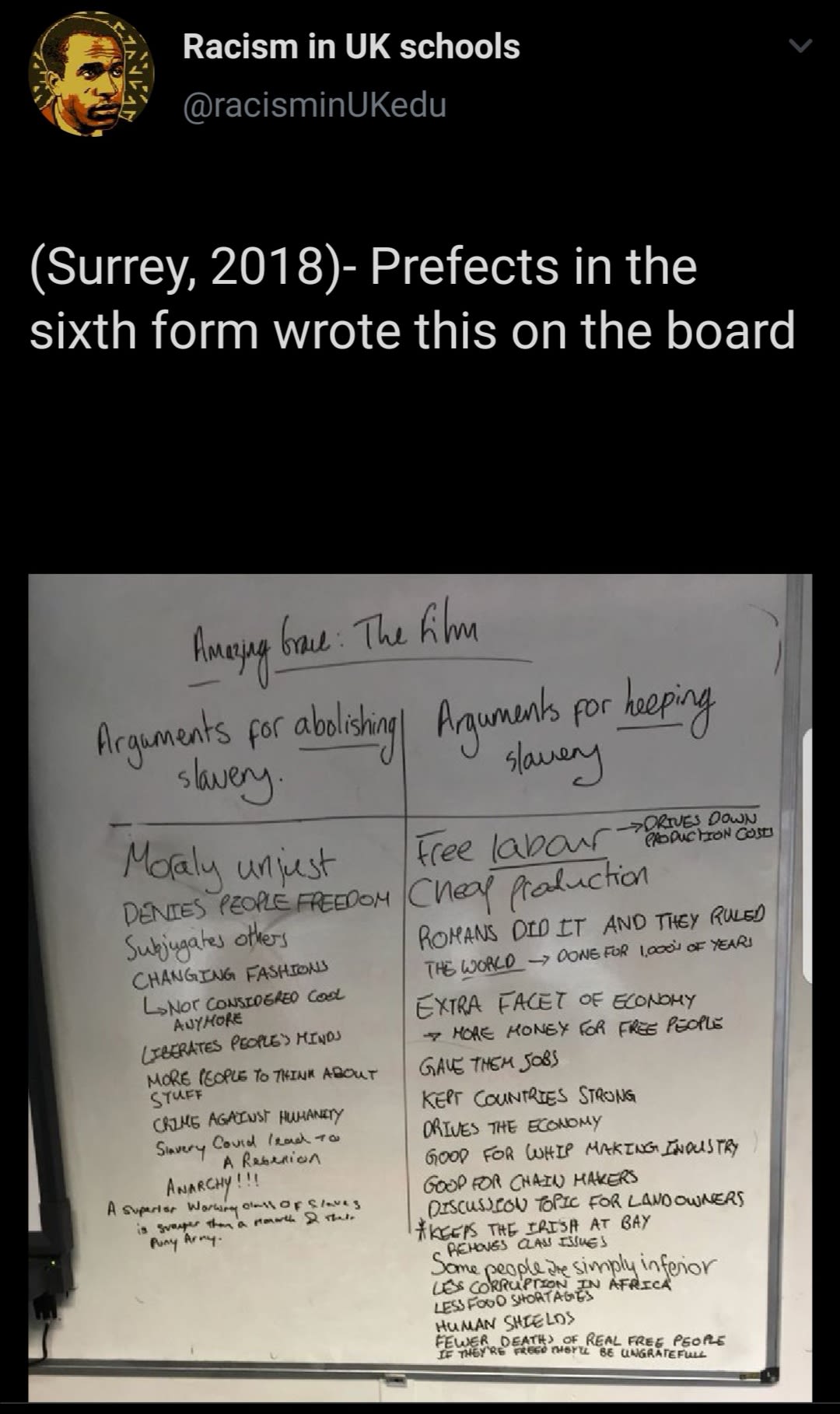

Since its inception in May 2020, the Twitter account 'Racism in UK Schools' (@racisminUKedu) quickly became an outlet for young people to recall incidents of microaggressions and explicit racism at their respective schools.

The account founder (who wishes to remain anonymous) said: “Initially I'd envisioned a safe space for people to share first-hand experiences, show solidarity and possibly spread awareness.

“But when the stories came in on Day 1, I soon realised this had to be actively tackled on a broad, institutional level.

“We received one story that dated back to 2003 which proves these experiences don't just leave you when you leave school.”

PICTURED: Screenshot taken from @racisminUKedu on Twitter

PICTURED: Screenshot taken from @racisminUKedu on Twitter

The account has posted more than 2000 incidents and gained over 6000 followers. Contributors have been encouraged to launch individual petitions and investigations to seek answers.

Several schools have since issued apologies.

“The current climate and the timing were perfect. Before, students were often punished for coming forward with such stories but in lockdown, they've felt protected at home,” she added.

“I believe the curriculum, particularly a eurocentric one, can foster dangerous environments in schools. Not learning how minorities have contributed to British society makes it easier for students to demean others.”

— Racism in UK schools (@racisminUKedu) June 8, 2020

Graveney, a popular academy secondary school in Tooting, has been challenged by current pupils, ex-students and teachers over allegations of racism and bullying.

'Graveney Stories of Racism' on Instagram garnered more than 2000 followers since its first post on June 17th.

The campaign started after a video went viral of a Graveney girl mocking the death of George Floyd in a social media 'challenge'.

One campaign member said: “The volume of stories we received allowed us to identify some of the root causes of racism and discrimination within the school.”

Graveney School set up a ‘Change Council’ in response to the allegations to further explore the issues raised.

The campaign founders, who are recent alumni, presented eight demands to the school including cultural and religious training, diversifying the staff body and decolonising the curriculum.

‘Decolonise the Curriculum’ is a long-running movement, most recognisable in UK universities, that addresses the sustained colonial legacies upheld in western-centric academic disciplines.

Similar school-oriented campaigns such as Impact of Omission have also called for educational reform after releasing a survey examining the British curriculum on June 1st.

The initiative founded by two university students has collected more than 56,000 responses.

Collated data showed that The Tudors were studied by 87% of respondents while 38% studied The Transatlantic Slave Trade. A further 7% studied Indian independence and the end of Empire.

Survey respondents attributed the lack of diversity in curriculum material to former Education Secretary, Michael Gove's decision to make colonial history modules non-compulsory in 2013.

Co-founder Nell Bevan said: “The response to the survey has been incredibly reaffirming because it's not just a problem that Esmie [co-founder] and I experienced but something shared by many.

“This is a problem that people recognised instantly having recently realised how much content was omitted in school.

“I felt overwhelmed and motivated by the number of responses, but also equally angry at the state of the country's education as it has completely reinforced the issue.”

A Runnymede Trust report on race and racism in English schools published in June 2020 called for increased racial literacy and greater BAME representation in the teaching workforce.

Author of the report Dr Remi Joseph-Salisbury at the University of Manchester said the transformation of education and a reckoning with colonial legacies was key to tackling racism in society.

“Anti-racist education should be based on an understanding of racism as a structural and historical phenomenon as well as an interpersonal one. As one teacher suggested of the curriculum, ‘at the moment it tends to deal with how language and individual acts of racism are wrong, but are we teaching about structural racism? To teach about colonialism and the empire and things like that?’ Through this re-envisioning of the curriculum, white students could be engaged with considerations of white privilege, power and complicity, in order to better understand and question their position in contemporary society. Simultaneously, BME students might also engage with content that prepares them for life in a racist society.”

However, one proposed review to reevaluate the English history syllabus and add more Black and minority ethnic histories was rejected by the Department of Education on July 30th.

The letter addressed to schools minister, Nick Gibb, and signed by cross-party MPs recommended including the Windrush generation and the contributions of former colonies in shaping Britain.

Liberal Democrats’ education spokesperson, Layla Moran told the Guardian that the request could have given more space to the historical injustices that have led to racism.

YOUTUBE: Marking Windrush Day in Lewisham by LEWISHAM COUNCIL

YOUTUBE: Marking Windrush Day in Lewisham by LEWISHAM COUNCIL

Since 1985, numerous government reports on race and ethnicity have substantiated the prevalence of racism in every state level. The Macpherson Report published in 1999 following the Stephen Lawrence Inquiry said:

“If racism is to be eradicated there must be specific and co-ordinated action...particularly through the education system.”

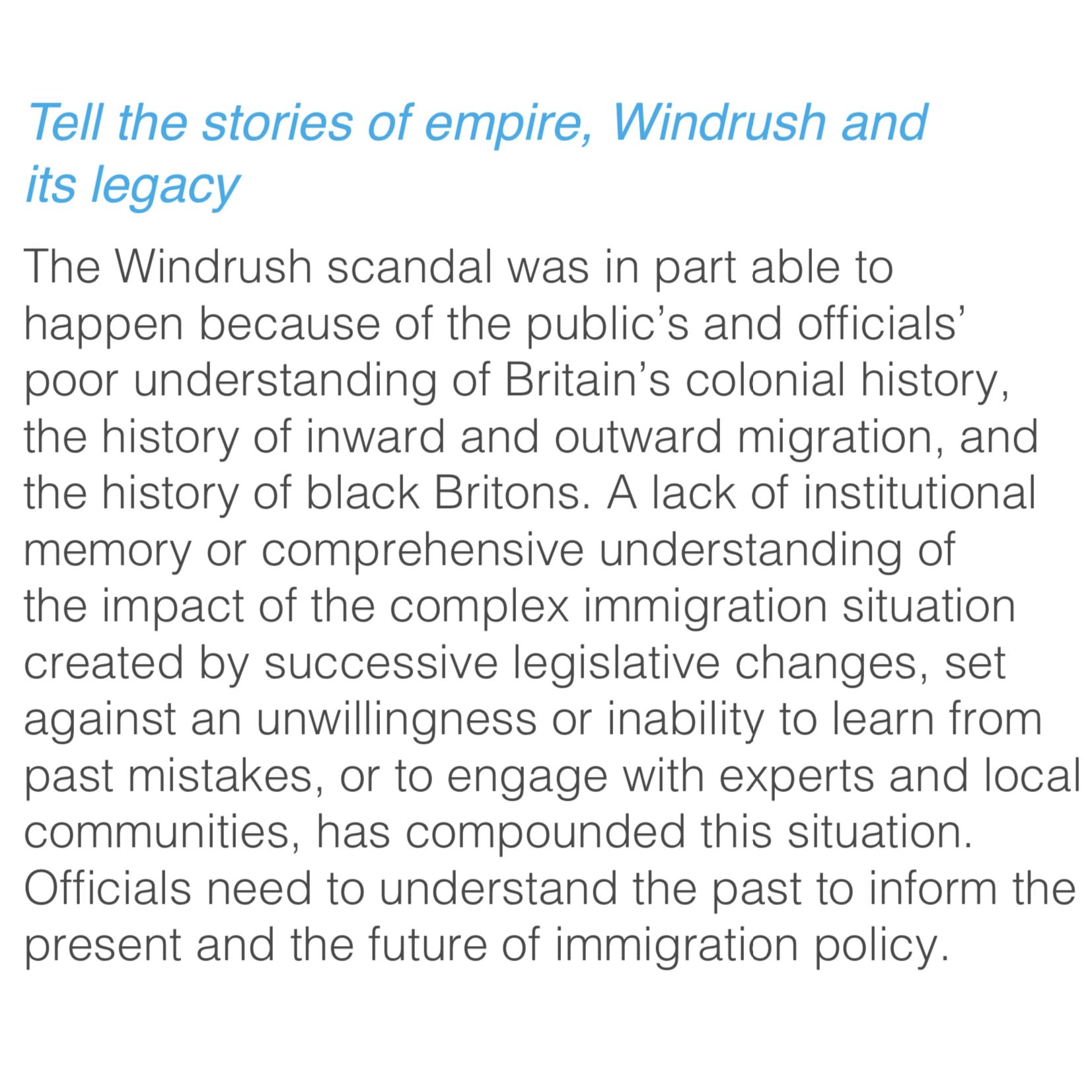

UK social enterprise, The Black Curriculum, also made a case for instating colonial history as a mandatory module by citing the Windrush Lessons Learned Review published in March 2020.

PICTURED: Windrush Lessons Learned Review by WENDY WILLIAMS (March 2020)

PICTURED: Windrush Lessons Learned Review by WENDY WILLIAMS (March 2020)

The education campaign, founded in 2019, emphasised that a loss of identity and belonging was a unifying sentiment amongst young people in Britain who were not taught their history.

In a report published by The Black Curriculum in January 2020, one of four recommendations to the education sector stressed the importance of making space in mainstream curricula.

“Teaching Black history not only benefits Black students, but it is also beneficial to British society as a whole: The cognition which ensues allows us as a nation to collectively pause and reflect on race relations. Widening the scope of Black history study can also help society to unravel many of the racial stereotypes that linger into the present.”

Anti-racist activism garnered the attention of millions in lockdown but beyond words of apology and solidarity from schools, the provision of real change for students still remains uncertain.