Dirty Thoughts and Cleaning Minds

The Impact of Undiagnosed OCD

What do you value the most?

Not just which of your possessions would sell for the most money, or which activities you have the most fun doing? What do you value the most?

What are the foundations of your identity, the things upon which you are built? What is it that gives your life meaning?

For virtually everyone, the answer to these questions will include a sense of security, their health and bodily integrity and their relationships to those closest to them.

It may extend to things like their moral compass, their sexual identity, or their religious faith.

These aren’t superfluous additions to a person’s life that bring them fleeting pleasure.

They are the essential prerequisites to pleasure being possible at all.

Without them, a meaningful existence becomes almost impossible.

There is a condition which systematically tries to strip away these things, little by little. If left unchecked, it will poison everything its sufferers hold dear and turn their own minds into Weapons of Self Destruction.

That condition has a name. A name that many will say glibly but precious few will understand.

You’ve almost certainly heard of it, since it impacts over 160 million people worldwide: Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, or OCD.

You’re getting it wrong

OCD is a complicated disorder, which makes explaining its nature a challenge. Much easier, however, is pointing out exactly what OCD is not.

It is not preferring things to be neat and tidy. It is not doing things in a particular order, or being fond of habits and routines. It is most certainly not (only) hand-washing or cleaning.

It is not something you have ‘a little bit’ of. It is not something that ‘everyone has’. It is not ‘just worrying a lot’.

In short: it’s not what everyone thinks of, and talks about, when they hear the acronym OCD.

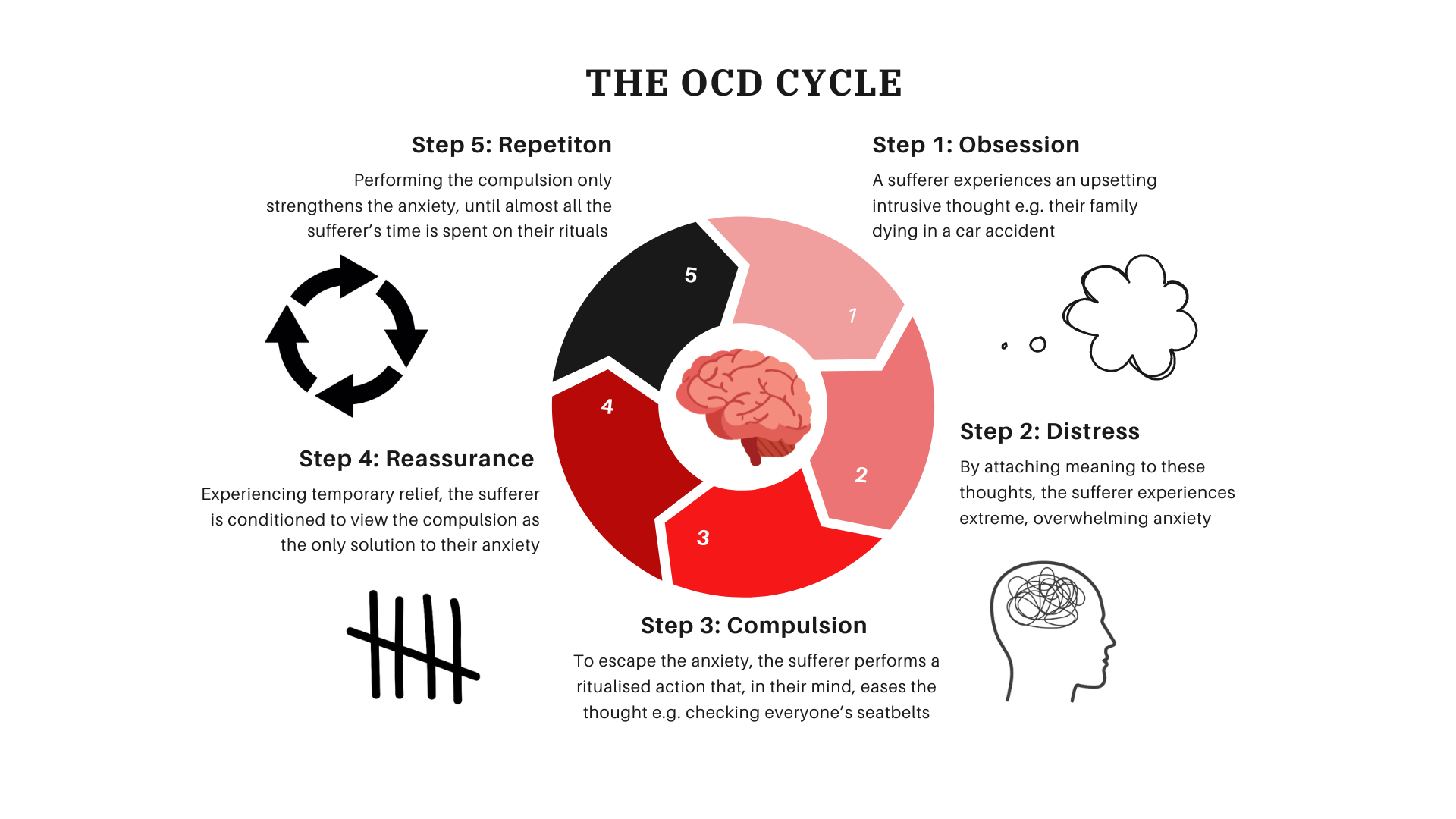

At its most basic level, OCD is a severe anxiety disorder that features both intensely negative and unwanted thoughts (‘intrusive thoughts’) and excessive ritualised behaviour that attempts to soothe the anxiety the thoughts cause.

The contents of OCD intrusive thoughts vary from person to person, but a common through-line is that they attack what is most important to the sufferer, hence the individual's desperation to eliminate them.

Often, they come in the form of a question: What if my partner is cheating on me? What if I’m secretly a paedophile? What if I lose control and kill someone?

In medical terms, OCD intrusive thoughts are ‘ego-dystonic’, meaning they are entirely contrary to the true beliefs and desires of the sufferer.

They aren’t really ‘their’ thoughts at all, more like synthetic copies of actual thoughts twisted to cause the most distress.

They are frequently accompanied by vivid mental images, which only strengthens fears that the thoughts reflect something true about the sufferer.

In the face of gut-wrenching panic or dread, an OCD sufferer will try anything, no matter how illogical, to achieve even brief respite from their intrusive thoughts.

Once these compulsions take hold as the only apparent escape from the obsessions, it becomes almost impossible to resist doing them.

In the Dark

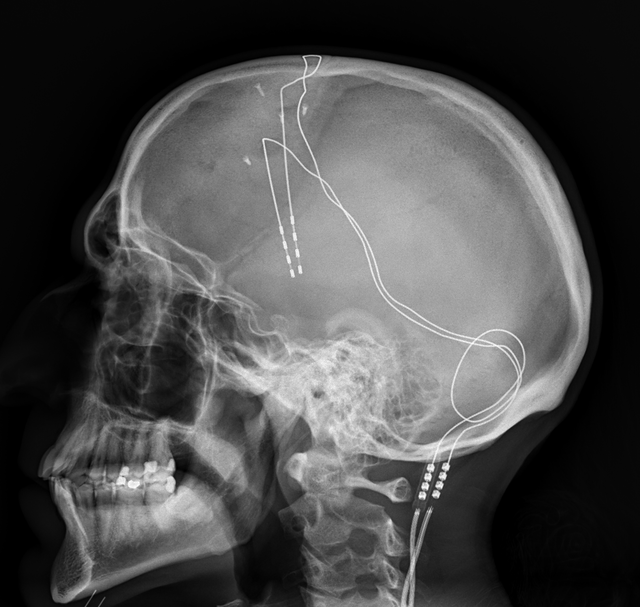

The biological underpinnings of these behaviours are very murky, with multiple proposed explanations for the emergence of OCD, rooted in the nervous system and the body's chemical messengers.

Brain-imaging of sufferers has revealed abnormalities in the orbitofrontal cortex (responsible for inhibiting actions) and amygdala (the seat of fear, anxiety and aggression).

Also implicated is serotonin, the neurotransmitter and hormone that helps regulate mood and induce a sense of calm.

Whatever its cause, no amount of abstract theorising can capture just how debilitating OCD actually is for those caught in a seemingly inescapable loop of tortured logic and inexplicable actions.

Anecdotally, OCD is at its worst in the time period between the onset of obsessions/compulsions and receiving an official diagnosis.

With no idea what is happening in their minds or why, sufferers can become terrified that they are fundamentally evil, that they are going insane and feel trapped in prison of their own thoughts.

If it sounds like a living nightmare, that’s because it is.

‘I just felt abnormal’

For YoungMinds mental health campaigner Paddy, that nightmare lasted five years.

As Paddy’s experiences make clear, OCD can latch onto something seemingly trivial and contort it into something that feels like a matter of life and death.

Paddy’s peanut related obsession also highlights another frequently misunderstood aspect of OCD, the form compulsions can take.

In many cases, compulsions will involve an outwards action, for example tapping a rhythm.

Yet in others they will be entirely internal to the mind of the sufferer.

These mental rituals might include silently repeating a list or prayer, replaying a memory over and over again or constantly returning to a thought to try and ‘figure it out’.

No OCD compulsion brings its sufferers happiness, at best they can help them keep their heads above water, but those that end up involving other people can be particularly difficult.

A lack of understanding among his peers about OCD left Paddy feeling increasingly marginalised at school.

By the end of Sixth Form he described himself as having few friends while he spent most of his time working to distract himself from his symptoms.

Health and disease is something OCD will often fixate on, so the COVID pandemic was predictably an immensely challenging time for Paddy.

At its most difficult, he was virtually unable to leave his house, in fear of giving the disease to a vulnerable person despite not having it himself.

Yet as hard as these times were for Paddy, he is able to reflect on them and feel a great sense of pride.

Those memories now serve as a yardstick for just how much progress he has made in the interim and a reminder of how much more manageable his condition was post-diagnosis.

He said: “It was a relief because I realised I'm not the only person feeling like this in the world and it's not my fault that I'm feeling like this.

“It’s not something that I'm doing. I'm not the cause of it; it's just something I've got.”

This knowledge was what gave Paddy the confidence to begin to resist his compulsions and claw back the control over his life that OCD had usurped.

Though undoubtedly not easy to hear, his diagnosis was simultaneously very liberating.

He said: “It's sad in some ways, to know that I've got OCD for life. It's not something I'm going to grow out of.

“But if I want these dreams, if I want to achieve what I want to achieve, then I've got to push myself and I've got to do what I want to rather than let it ruin things.

“At first I thought, what am I going to do with my life? But then I felt empowered knowing that it was up to me to live it on my terms.”

‘I feared I wasn’t even human’

Hearing Paddy speak so touchingly about his journey with OCD brought me immense satisfaction in a way that went far beyond journalistic fascination.

Our conversation was the first time I’d ever spoken to another person who suffered from the illness that had left me feeling isolated from everyone around me for large chunks of my adult life.

Officially, my nightmare was only three and half years long, but the seeds it were planted in my childhood.

At age nine, I can remember crying to my parents because a particular melody was stuck in my head and I was afraid it would never go away.

I used to have to tap out or hum that melody tens or even hundreds of times a day and if it didn’t sound just right I would have to start again. I remember it note for note even now.

As I grew older, my obsessions gradually became darker. The more I learned about the scary things in this world, the more ammunition my OCD received to use against me.

I would go for months stuck on a particular theme, at one point pinching myself so hard my skin would bleed because I thought it was the only way to cancel out bad luck from seeing the colour red.

Then, in an instant, my brain would latch onto something else to obsess over. Suddenly it made no sense to be pinching myself, that wasn’t going to stop me from having a stroke.

The only way to do that was to repeat my name, address and contact details as often as I could to check I could still remember them.

It was at age 16, following a personal loss, that things became unbearable.

My obsessions had blackened even further, and now instead of the harms that might come to me, my mind zeroed in on all the harm I could do to other people.

The details of some of my intrusive thoughts from that time period are difficult for me to talk about, more than half a decade later.

I was bombarded with the most lifelike images of committing acts of violence against my friends and family that my brain could conjure up.

With no diagnosis and no awareness that my brain's self-preservation mechanisms were misfiring so badly, I became convinced that those intrusive thoughts and urges were just who I was.

I feared I wasn’t even human and was instead a poor replica of one who had conned everyone around me into not seeing who I really was.

There aren’t really the words to capture the sense of solace I felt when I finally received my diagnosis.

Of course, simply knowing it was OCD didn’t make the obsessions any less unpleasant or the compulsions any easier to resist.

Yet, at last I had a glimmer of hope that my worst fears about who I was might not be based in reality - a light at the end of what had been a very dark tunnel.

Knowing that what I have has a name, that other people have it too and that there are treatments for it provided more relief than a thousand compulsions ever could have.

All at Once

OCD very rarely acts alone; it certainly didn't for me.'t

There were always other concerns beyond my compulsions, ranging from my relationship with alcohol to my body image.

OCD has an astonishingly high rate of comorbidity - the prevalence of more than one disease in a single individual.

In total, 75% of all OCD sufferers will also experience at least one other mental illness simultaneously with their OCD. More than a third of sufferers will have two or more.

Among the most common are major depression (31%), social phobia (11%), eating disorders (8%) and panic disorder (6%).

A recent Italian study found that nearly 45% of their sample of OCD patients also met the diagnostic criteria for Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, or cPTSD.

Developed following repeated exposure to traumatic events over an extended timespan, cPTSD is characterised by difficulties in controlling emotions, an inability to form stable relationships and persistent feelings of worthlessness.

Without a diagnosis, and therefore no formal way of managing these toxic maelstroms of internal instability, it is perhaps little surprise that up to 27% of OCD sufferers will develop an alcohol or drug abuse disorder in their lifetime.

If anything, that figure may underestimate the co-occurrence of OCD and substance abuse disorders (SUDs), since many of those seeking treatment for SUDs will have their OCD symptoms missed.

I thought I was going to be institutionalised for the rest of my life’

OCD, by its very nature, lends itself to sufferers concealing their symptoms. It is extremely difficult to admit to anyone that you are having graphic or disturbing thoughts, let alone your family and friends.

Sufferers are constantly in a state of hypervigilance for how they may be perceived by others, dreading that if anyone else found out what was happening in their minds, they would be shunned.

This fact, coupled with OCD’s propensity for comorbidities and a general lack of understanding of OCD among clinicians, contributes to lengthy waiting times between the onset of symptoms and diagnosis.

Paddy and I were the lucky ones. Our nightmare ‘only’ lasted half a decade or less. The average person with OCD will wait 13 years for a diagnosis after their symptoms emerge and a further two years for treatment.

For Erika McCoy, an artist and advocate for the International OCD Foundation, it lasted 19 years.

Raised in a community in which religious faith played a central role, Erika - now 33 - has battled since age five with her OCD’s attempts to weaponise her beliefs.

She said: “My main theme all comes back to moral and religious scrupulosity. Am I a good person? Did I do something evil? Am I going to hell? Is God going to punish me?”

Latching onto the religious significance of the number six (through its association with Satan) and the folk superstitions around the number 13, Erika attempted to avoid these numbers at all costs.

She said: “I would clean things in threes, fives and sevens. I was always doing maths in my head to try to find a way to avoid doing sixes - multiplying, dividing, adding, subtracting, to make sure there was never six and 13.”

Compounding the ceaseless war inside her mind was a total lack of understanding about OCD from the members of her faith community - whom she relied upon for support.

At a time when Erika was already battling with immensely distressing intrusive thoughts that her boisterous son might be the Antichrist, Erika was told she was possessed by demons.

The duress of this ‘spiritual warfare’ (to use Erika’s own description) became so overwhelming that Erika came to believe that her only option was to take her own life.

Fortunately, her attempt was unsuccessful and eventually, at age 25, Erika was finally given an explanation for everything that had been tormenting her.

She said: “Before I got the diagnosis, I thought I was so mentally ill that if anyone ever found out what was going on in my head or the things I was thinking, that I was going to be institutionalised for the rest of my life.

“It puts you in a state of sheer terror for so long that when I got the diagnosis I was so relieved because I thought it was something I've never even heard of.”

Stolen Time

Erika’s story highlights another element of OCD that often flies under the radar.

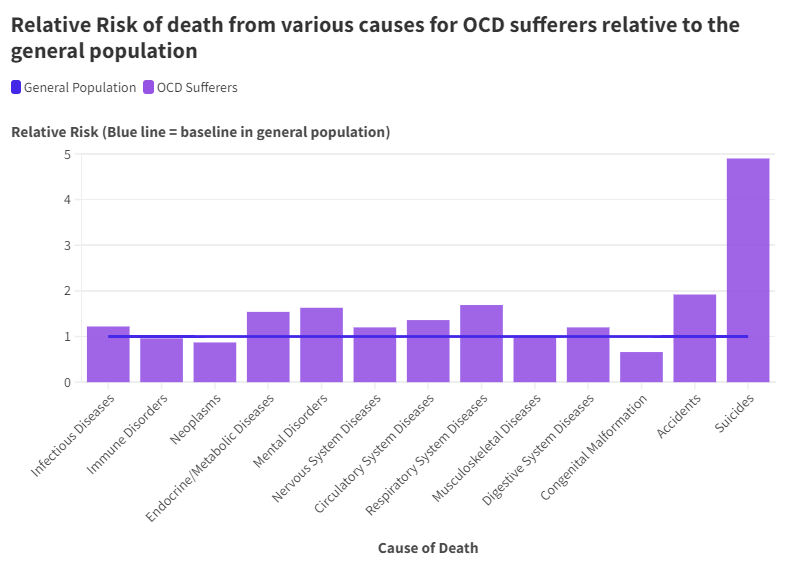

Not only does OCD reduce the quality of life that sufferers have, it reduces the length of that life.

A 2024 study carried out by the British Medical Journal found that people with OCD were 82% more likely to die from any cause than those without it.

That same study broke down the comparative fatality rates from various different natural and unnatural causes, with OCD sufferers at greater risk almost across the board.

The presence of OCD increased the relative likelihood of dying from infectious diseases, diseases of the endocrine, nervous, circulatory, respiratory, musculoskeletal and digestive systems, as well as from other mental disorders.

In fact, OCD was only not associated with a higher risk of death for neoplasms (cancers) and congenital malformations (birth defects).

When concentrating on unnatural causes of death, the disparity is even starker.

OCD sufferers are almost twice as likely to die in an accident that those without the condition and are alarmingly nearly five times as likely to die by suicide.

Source: Fernández de la Cruz L, Isomura K, Lichtenstein P, Larsson H, Kuja-Halkola R, Chang Z, D'Onofrio BM, Brikell I, Rück C, Sidorchuk A, Mataix-Cols D. All cause and cause specific mortality in obsessive-compulsive disorder: nationwide matched cohort and sibling cohort study. BMJ. 2024 Jan 17

Source: Fernández de la Cruz L, Isomura K, Lichtenstein P, Larsson H, Kuja-Halkola R, Chang Z, D'Onofrio BM, Brikell I, Rück C, Sidorchuk A, Mataix-Cols D. All cause and cause specific mortality in obsessive-compulsive disorder: nationwide matched cohort and sibling cohort study. BMJ. 2024 Jan 17

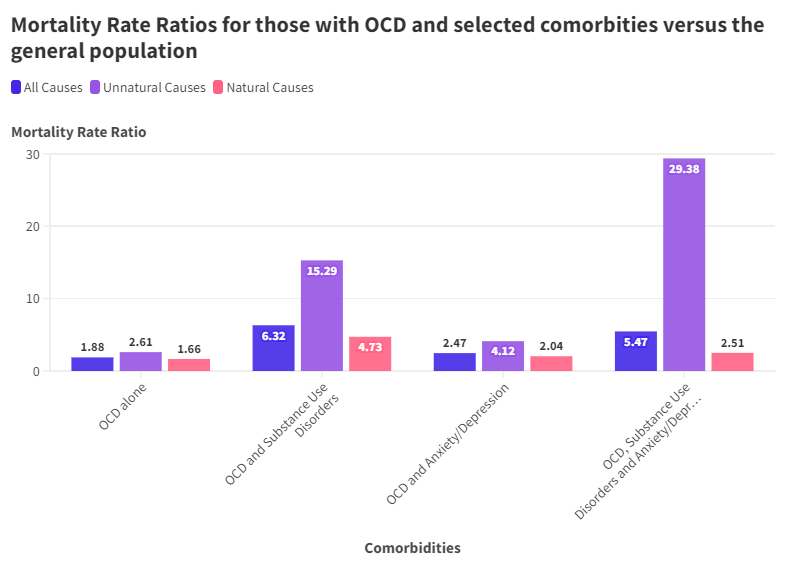

Looking beyond OCD in isolation and accounting for its comorbid potential reveals just how vulnerable people who have OCD truly are.

In every combination of OCD, anxiety/depression and substance use disorders, the overall risk of death and the risk of death from natural causes is higher than in the unaffected general population.

Yet what is even more startling are the mortality rate ratios (the proportion of people with the conditions who die from them relative to the deaths rates among people without it) from unnatural causes - the bulk of which will be suicides.

Having both OCD and anxiety/depression makes a person four times more likely to die unnaturally than someone with neither.

For OCD and substance use disorders, this rises to a greater than sixfold increase in the risk of death.

When all three are present, sufferers are a staggering thirty times more likely to die unnaturally than the average unaffected person.

Source: Meier SM, Mattheisen M, Mors O, Schendel DE, Mortensen PB, Plessen KJ. Mortality Among Persons With Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in Denmark. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016 Mar;73(3):268-274.

Source: Meier SM, Mattheisen M, Mors O, Schendel DE, Mortensen PB, Plessen KJ. Mortality Among Persons With Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in Denmark. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016 Mar;73(3):268-274.

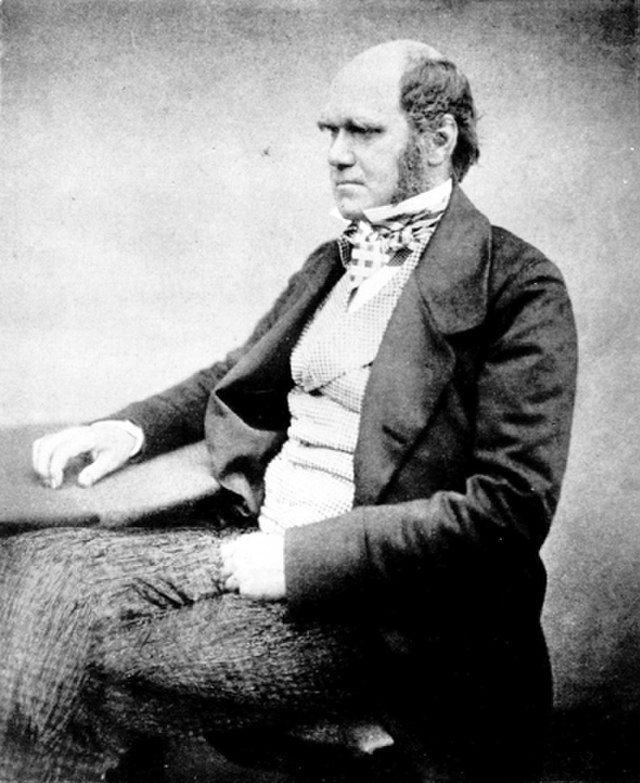

Picture Credit: Messrs. Maull and Fox

Picture Credit: Messrs. Maull and Fox

Charles Darwin was plagued by disturbing thoughts about his health and appearance. He once wrote to a friend: " I could not sleep and whatever I did in the day haunted me at night with vivid and most wearing repetition."

Picture Credit: H. Lenthall, London

Picture Credit: H. Lenthall, London

Though not formally diagnosed in her lifetime, Florence Nightingale is believed to have suffered from health obsessions that caused her to wash her hands over a 100 times a day.

Picture Credit: Capitol Records

Picture Credit: Capitol Records

Frank Sinatra's wife Barbara revealed that he battled worsening cleaning compulsions throughout his life, which at their worst led him to shower 12 times a day.

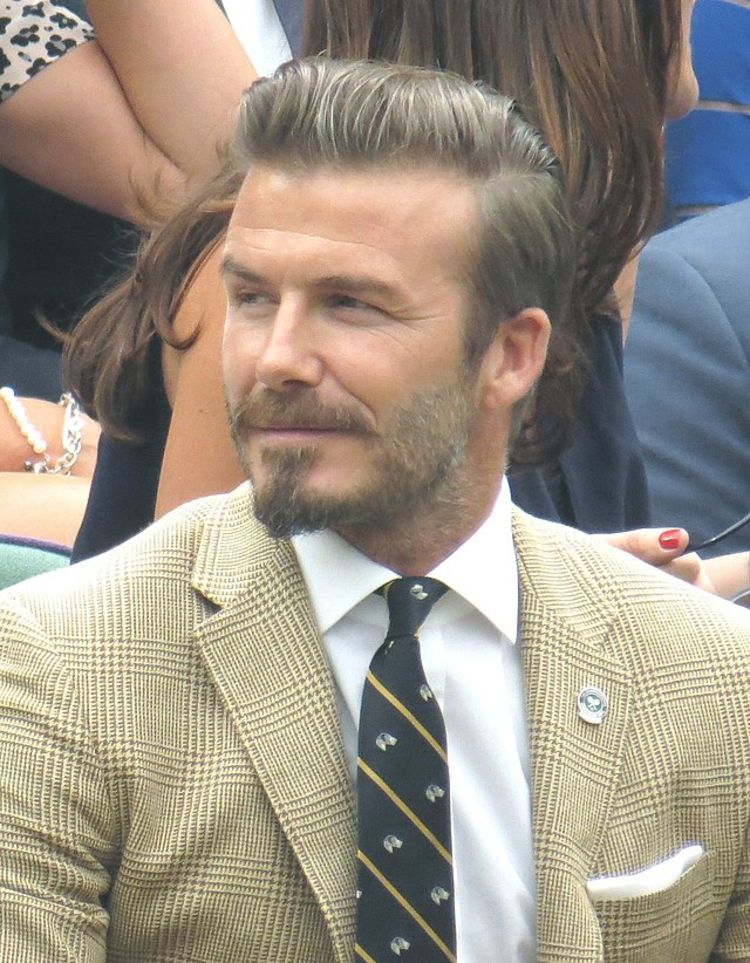

Picture Credit: Brian MInkoff-London Pixels under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Picture Credit: Brian MInkoff-London Pixels under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

As one of the most high profile celebrities to reveal an OCD diagnosis, David Beckham has been candid about his obsessions relating to perfectionism, symmetry and counting.

Making a Mess

As is hopefully clear by now, living with OCD can be utterly debilitating, constricting the space the sufferer has to live their own life until their compulsions require all of their waking attention.

Yet if the lived experiences of those with OCD is so far from the popular perceptions of the disorder, there are some uncomfortable questions to be asked about the way people talk about the disorder.

Why are people so willing to joke about OCD in a way they never would with other serious health conditions? No one ever says ‘I’ve got a little bit of cancer’.

Why do people so freely diagnose themselves and others with a disorder they most likely do not have and understand very little about.

At the risk of sounding cliche, the apportionment of blame begins, as it usually does, with the media people are exposed to.

There are a litany of characters strewn across television and film who lean into common tropes about OCD in the hopes of eliciting some cheap laughs.

Some of these culprits are among the most famous characters in pop culture: the repetitive door-knocking of Sheldon Cooper from The Big Bang Theory or hyper-cleanliness of Monica from Friends spring to mind.

Neither of these characters are ever explicitly referred to as having OCD, but in the absence of clarification to the contrary, their audiences are free to jump to erroneous conclusions.

What these characters and those like them fail to capture is the anxiety and dread that motivates the performance of compulsions.

As Paddy put it: “I don't feel pleasure in performing my compulsions. I feel a lot of the time it's quite shameful.

“It’s feeling the pressure of the world on your shoulders, that if I don’t do this then something's going to go badly and I will feel guilty about this moment for the rest of my life.”

When OCD does get named on our screens, rather than capture the variety of ways it manifests, the entertainment industry is content to default to cleaning as a substitute for any meaningful depth.

To give one example, on AJ Tracey’s recent ‘Wifey Riddem 4’, he casually drops the line: "OCD, I couldn’t handle the mess."

In six words, he manages to reduce a medical condition that can consume people’s entire lives into a punchline about his relationship issues.

He’s far from the only one.

Erika has her own theories as to why this is: “I think the compulsions that have been given the most attention are the ones that are more socially acceptable.

“It comes out as a joke but when sufferers start talking about taboo subjects, people get quite uncomfortable.”

There was a reality TV show on Channel 4 that ran for nine seasons called Obsessive Compulsive Cleaners. No one is making nine seasons of television about being afraid you want to commit bestiality.

Themes of contamination are a very real part of OCD, but they are not universal and those who clean because of them do not derive any joy from performing those rituals.

If people are only ever spoonfed the most surface level, stereotyped portrayals of OCD, is it any wonder that the condition is so badly misunderstood?

This kind of misinformation is not just a source of frustration, it has a real and devastating impact on the lives of those who actually have the condition.

None of my early obsessions ever related to cleanliness or contamination. I had no idea that other manifestations of OCD were even possible.

Even now, I wonder how much hurt I could have avoided if I’d realised sooner that what I was going through was OCD all along.

Part of the reason that people with OCD can wait for 13 years after their symptoms develop before getting a diagnosis and help is that they have no idea what to look for.

Cleaning it up

I’ll ask again: what do you value the most?

For me, that starts with my family and friends, who I felt I could trust with the intrusive thoughts I was most ashamed of.

When enduring any mental illness, but especially with OCD, it is so important to be listened to non-judgmentally and to have that option to reach out when symptoms flare up.

It extends to NHS Talking Therapies, where anyone who suspects they might have OCD can self-refer to receive assistance in breaking the cycles of obsession and compulsion.

It reaches out to Paddy, who has used his role with YoungMinds to campaign for the introduction of mental health hubs in schools.

It includes Erika, who uses her artistic talents to paint rocks with the information about OCD and the International OCD Foundation and leaves them in public for people to find.

It encompasses the community of social media pages that provide accurate portrayals of OCD and combat the myths that surround it:

Finally, it ends with the charities that work tirelessly to provide support, guidance and treatment to those who need it most:

International OCD Foundation: https://iocdf.org/

OCD UK: https://www.ocduk.org/

OCD Action: https://ocdaction.org.uk/

Triumph Over Phobia: https://www.topuk.org/

Without these people and others like them, thousands of people will be forced to carry on an unwinnable fight against their own brain.

Without these people, sufferers without a diagnosis will continue to struggle in vain until they reach a crisis point.

Without these people, will the nightmare continues.

But it doesn't have to.

Credits:

Dome of the Church of Holy Sepulchre: Andrew Shiva under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Hand washing instructions: BurtAlert under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.

X-ray of deep brain stimulation in OCD: JMarchn under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Man standing in front of the window: Sasha Freemind on Unsplash

Subjective impression of a panic attack: Yitzilitt under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. A black and white filter has been applied to the image.

Xanax: AlexandraAngelina under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Hospital bed near couch: Martha Dominguez de Gouveia on Unsplash

Reaching Out, Derry/Londonderry : Kenneth Allen under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.

Videos, infographic, graphs and words: Ben Coneybeare