Failure to launch? What is the satellite economy & why do we need it?

Eurostar 3000 satellite, 2000. Science Museum, London.

Eurostar 3000 satellite, 2000. Science Museum, London.

As the first satellites to be launched from UK soil failed to reach outer-space, it’s worth questioning why we need the satellite economy, and how these pieces of AI reflect our preoccupations.

According to the United Nations Outer Space Orbits Index, there were approx. 7,500 satellites in the Low Earth Orbit (LEO) region in 2021. Added to this, Dr Abbie MacKinnon, Space Curator at the Science Museum, estimates that there are currently 23,000 defunct satellites floating in our near orbit. This doesn’t include millions of flecks of debris that hurtle through space at a lethal seventeen miles per hour.

In fact, the sky is so littered with ‘space junk’ that there is a small, flexible economy in clearing it up, as governments offer funding to private sector companies to do the job. As a result, imaginative solutions to fishing debris range from mechanical arms, to space-harpoons and nets suitable for zero-gravity. Not your average fishing-trip.

The implications of not clearing up our rubbish are fatal, although missions to adjust the trajectories of stray tech are seldom and often made in advance of a shuttle-launch. Intrepid astronauts such as Paralympian John McFall or Alyssa Carson, the Advanced Space Academy’s youngest graduate, could otherwise be thwarted in their journeys to the International Space Station by the debris in their ship’s path. ESA (The European Space Agency) is now actively exploring plans to regulate the deorbiting of satellites after four years of their retirement.

What is it all there for? You’d be forgiven for associating satellites with excess channel-flicking choices or your car’s temperamental GPS. The serious implications of fast evolving satellite technology are under publicised.

In 2016, satellites were able to capture the scale of disease and death among Syrians in a Jordan refugee camp with strikingly detailed images. Similar earth monitoring has since been employed to track the conditions of displaced peoples and diaspora.

Dr MacKinnon cites the Russian-Ukraine conflict as the most vivid, recent example of how government defence satellites have brought the real-time movement of troops into the public domain. She says:

“The Ukraine-Russia war is a clear example of how satellite imagery has not only helped with strategic defence, but has brought awareness of the movement of troops, and the scale of threat, to public awareness.”

In an era of escalating crises, satellites have been at the cutting-edge of combating climate change. From such an elevated perspective, satellites produced by organisations such as industry-leader, Planet Labs, can identify movements in ice-caps, gas, tidal waves and migrating populations of species. “This hard to obtain information can help us make decisions such as where to plant crops, have controlled forest burns and how to respond to the changes of the Ozone layer,” says MacKinnon.

“Without satellite imagery, we’re really flying blind.”

The race to net-zero is partly why the investment and promotion of new satellite technology is high on the export agenda of nations, as allies monitor expected atmospheric change and bolster domestic economies in the process. Since the conflict in Ukraine, EU countries have discussed ways to collaborate on a satellite constellation that would ensure independent monitoring of any future conflicts, without reliance on Space X or the USA.

But to many it will seem counter-intuitive that while 22% of UK citizens live in poverty, a space infrastructure is planned that will see five Space Ports across England, Wales and Scotland as well as intended research and training hubs.

Although Spaceport Cornwall is the result of over 7 million pounds of international seed funding, it is likely that the infrastructure of planned space hubs and ports up and down the UK will partially be the product of increased funding to the UK Space Agency, which in 2021 was an expected £600 million. Compare this with the shrinking economies of the UK manufacturing and wired telecoms industries, and a lively debate could be formed.

However, it is possible that the investment in local ecosystems: employment, tourism and skills could potentially counter-balance a stratospheric spend. Dr MacKinnon says:

“Doubtless the space ports in England, Scotland and Wales will bring new jobs and economic benefits to the local areas, in the same way that Spaceport Cornwall has attracted investment.”

So while the electric car revolution is being lightly trumpeted by TESLA and politicians, the space infrastructure, enabling not only the launch of public sector and commercial satellites, but tourist journeys, is steadily gathering pace…

In a LinkedIn post by the UK Space Agency 9/1/23 -

Further afield, our knowledge of why foreign satellites cloud the skies is less clear. China, for example, a country that the west is experiencing increasing political and security tensions with, has an estimated 499 satellites spinning at its fingertips. Quite how many of these have spyware or defence missions is unknown. MacKinnon says:

“I don’t know the likelihood of how many Chinese satellites would be used in espionage, but it is safe to say that whatever we or other countries are doing, China is doing also.”

The question of who regulates where these floating sources of information are positioned cannot be fully answered. There is little regulation of airspace.

In theory, if Joe Bloggs up the street wished to start a telecoms company and raise enough money to launch one of Planet Labs' satellites, there would be no reason why he couldn’t, providing his reasons fell into the broad criteria.

While the privacy implications of living in a surveillance society are worrying, the climate and crisis resolution contribution of satellites reminds us that the closer we watch the planet’s changes from an aerial view, the closer we can get to managing them.

NASA satellite imagery of flooding in Chad Oct' 2022. Copyright NASA2022.

NASA satellite imagery of flooding in Chad Oct' 2022. Copyright NASA2022.

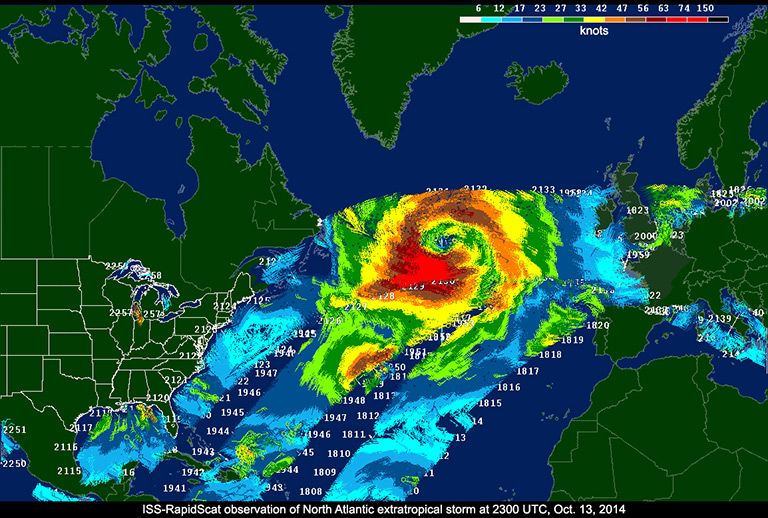

NASA satellite monitors a North Atlantic extra-tropical storm using colour coding of knots. Copyright NASA2022

NASA satellite monitors a North Atlantic extra-tropical storm using colour coding of knots. Copyright NASA2022