Farming and Diversity

Agriculture is one of the UK's least diverse professions, but a growing movement is attempting to bring about a change

What does a typical British Farmer look like to you?

You probably picture a man.

Presumably a white man?

You would not be so wrong in thinking so.

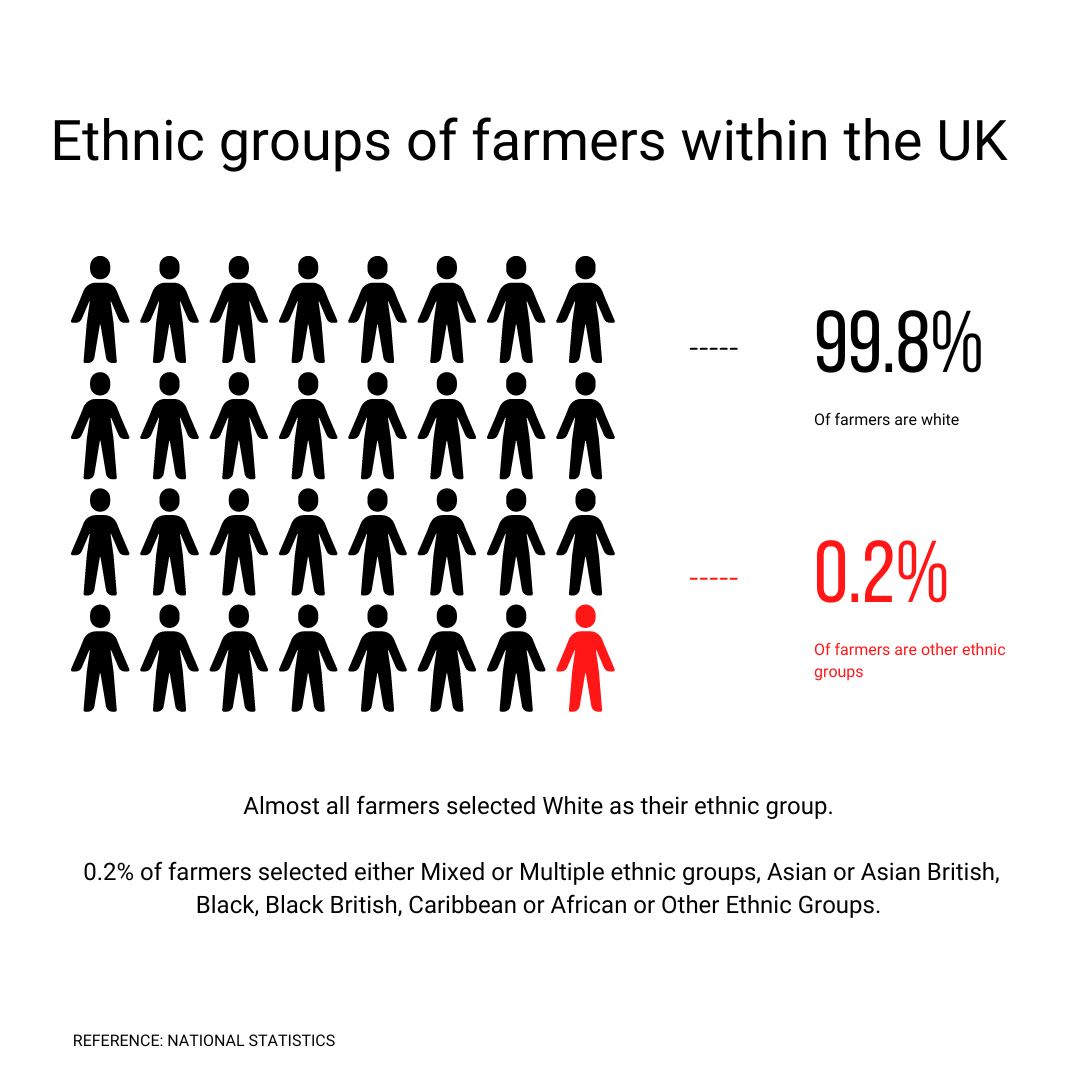

Data from National Statistics reveal 99.8% of farmers in the UK are white. But why?

Florence Freeman graphic. Source: National Statistics

Florence Freeman graphic. Source: National Statistics

Land is for the rich and the richer

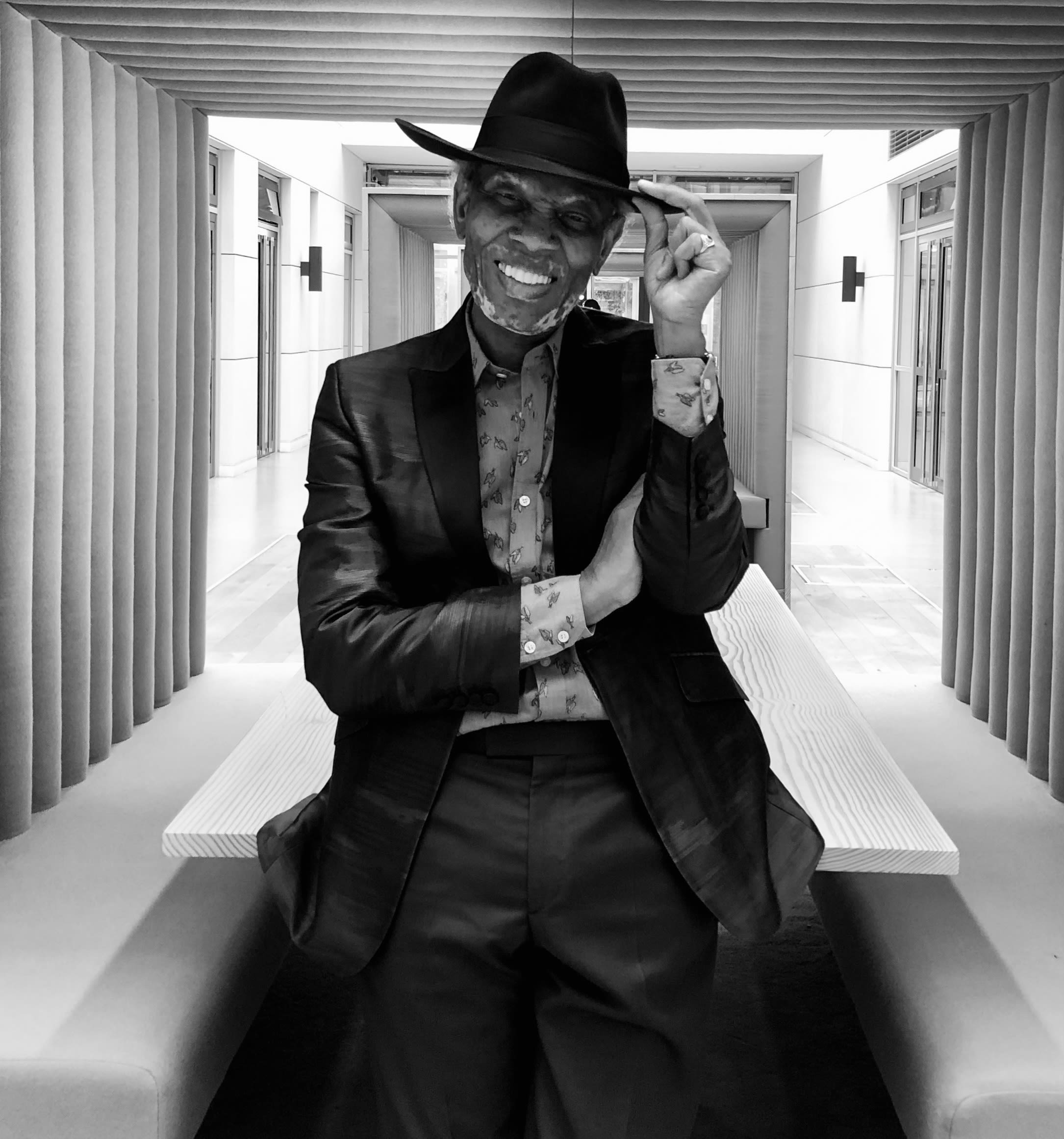

Photo by The Black Farmer

Photo by The Black Farmer

"Most farmers have had their land handed down through generations so unless you are very rich, the chances of you getting land is virtually impossible," says Wilfred Emmanual Jones MBE, best known as The Black British Farmer.

His story is like no other - from an impoverished immigrant to now a multimillionaire farming legend - he has exceeded all expectations.

Born in Jamaica, he was raised in inner-city Birmingham with eight brothers and sisters in a two-up-two-down leaving school with no qualifications.

Years later, Mr Jones would purchase a small farm in Devon where he would launch his own food business, fulfilling a lifelong dream.

“When I bought my farm 20 years ago I remember when I put up my first polytunnel and someone called the police because they thought I was using it to grow cannabis.”

His introduction to the rural southwestern town of Launceston must have been no less than a shock.

Land ownership has remained largely unchanged for centuries among the aristocracy and gentry.

Less than one per cent of the pollution owns half the land according to Guy Shrubsole, a British researcher, writer and campaigner.

See below to find out who land is divided between in the UK.

Florence Freeman graphic. Source: Guy Shrubsole, author of Who Owns England?

So how was a Black man from Jamaica who grew up in Birmingham able to buy land and most importantly, why is his move such a rare occurrence?

“A lot of people from the Caribbean are from rural farming backgrounds. If you go to the cities you have a lot of people of colour working in allotments,” he said.

“Farming is very much part of their DNA but they just don’t have access to it and people who are in control of land have never been held to account.

“Land is owned by the Church of England, The National Trust and many other big institutions. They lease and rent their lands out to traditional families.

“I’ve been advocating for decades now saying these intuitions should be doing something by having their land agents go out there and set aside a small percentage of your land that you’ll actually be leasing to people from non-traditional farming backgrounds.

Photo by The Black Farmer

Photo by The Black Farmer

“Until that happens you’ll never have diversity.”

Mr Jones believes stereotypes of farming as a profession have led to fewer Black people wanting to be involved.

But now he wants to educate those on the power of owning land.

“The agricultural lifestyle is pushed aside and looked down upon. In the past, the measure of success has been being a doctor or accountant,” he said

“But the industries that really have power are farming and food, which has been ignored and that is where all the power is.”

For years, Mr Jones has been trying to advocate for change within the farming and agriculture industries to bring about more diversity.

He believes with diversity, the profession can grow to greater lengths.

“The one thing about being a farmer that you know is diversity is key. If you don’t rotate your crops, you're going to get disease, if you don’t mix your breeding you’ll have issues.

“Nature tells us that diversity is essential for strong survival so why as an industry do we break that rule by not having diversity at all?

“You can’t exist without food, you can’t do food production without land so, therefore, the most fundamental thing about any country is why is there no diversity?

"Look at all these supermarkets, they’ll advertise and you’ll see black faces and you’ll see black people but that is not where the power is.”

“Change only comes when people stand up and say this is unacceptable.”

Mr Jones speaking about what needs to happen to the farming industry

British Veterinary Ethinicity and Diversity Society (BVEDS)

In 2016, Navaratnam Partheeban, a veterinarian and Issa Robson, a farm vet, created the BVEDS after finding no support for BAME vets, nurses and students facing discrimination in the profession.

Together, they aimed for three main goals - to raise awareness, celebrate differences and educate the masses.

“We wanted a group that could raise awareness and offer support; where people of colour could come and talk openly about their experiences,” he said.

“We also wanted to celebrate differences. We've all got these individualities and all this time we haven't been able to share or celebrate them.

“The last thing was education. Most people from the profession have come from privileged white backgrounds. How are they going to learn about it? We need to put out information that people can read about, and bring in allies.”

But despite the demand, during the start, not many people had come to reach out to the BVEDS.

“When we first started it was slow and steady. You’d get out and talk to people about it and get the odd one or two things but that would be it,” he said.

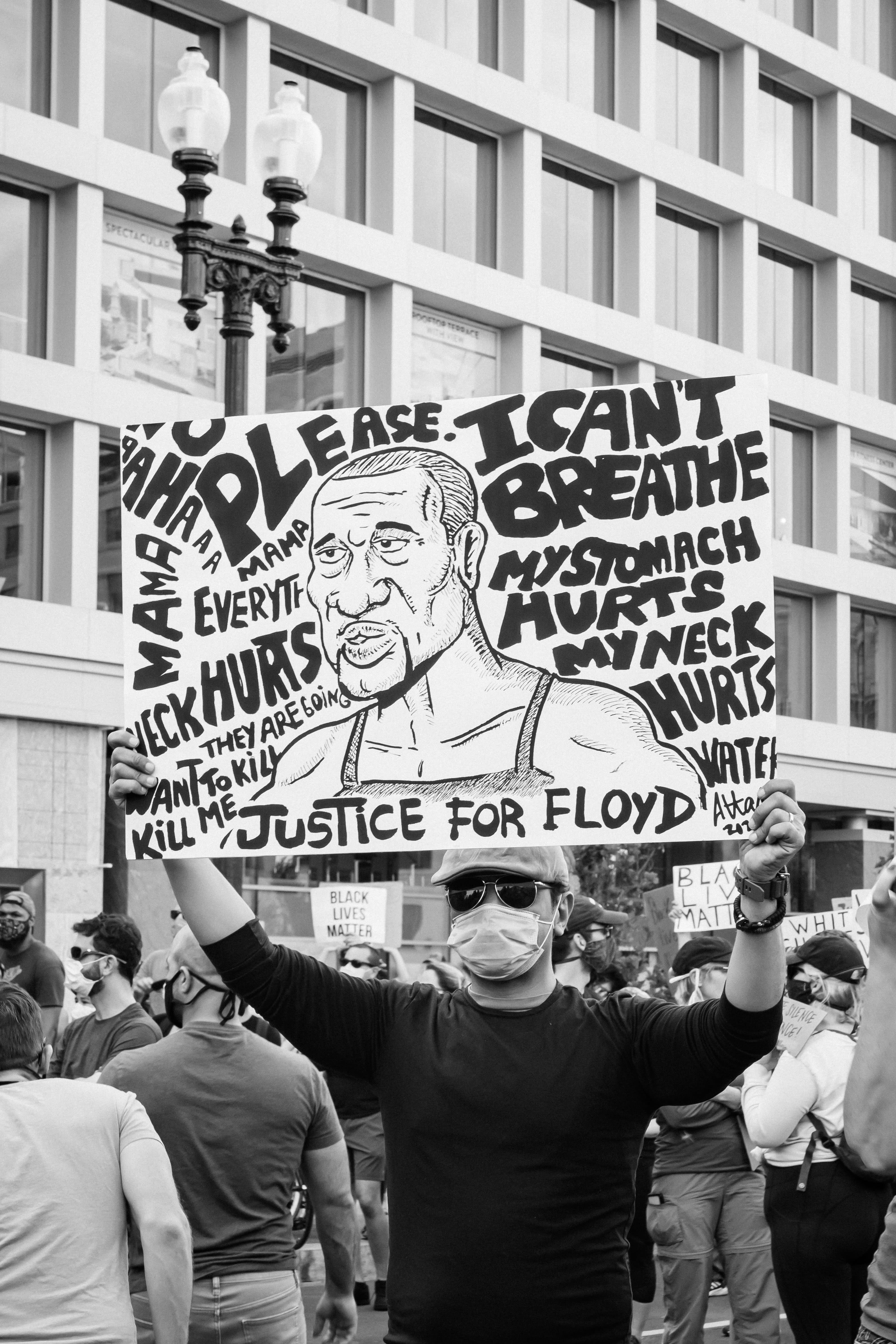

That was until May 2020 when George Floyd, a 46-year-old black man, was killed by Minneapolis police officers.

The death of Mr Floyd was captured by onlookers and shocked the world as many witnessed his harrowing last moments as officers knelt on his neck for almost nine minutes.

His death ignited historic protests around the world, and many in the veterinary profession in the UK felt they could no longer keep quiet about the racism and discrimination they faced.

“After the death of George Floyd, I probably heard as many stories in six months than I did in four years because I think people suddenly thought 'I don't need to put up with this anymore,” he said.

“For a lot of people, a lot of trauma, internal trauma suddenly came out. And I was on the phone every night for three or four hours talking to different candidates, different nurses, different vets. ‘This is what happens to me. What do I do about it?’

“People started to go I've gone through that. I've got this trauma inside me and seeing it on the TV, I now want to share what I've gone through.”

The company has grown over the years, working with university employers, regulation bodies and veterinary societies to make the progression more diverse and inclusive.

In 2021 Mr Partheeban and a group of other researchers conducted the widest study ever conducted in the veterinary profession, examining experiences of racism and its impacts on mental well-being in Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) veterinary professionals.

Together the team interviewed hundreds of BAME veterinary professionals to find out their experience of racism within the field and what could be done to improve it.

“A lot of people say they've experienced racism but they struggle to say how it made them feel. It's ofton difficult to put in words," he said

“So what we wanted to do is put it in boxes, how racism makes people feel, and then show the mental health impact of racism.

“We had 300-odd people apply for the survey which, you know, for a small profession, that's pretty good.”

And with their success, Mr Partheeban and his team are changing the minds of farmers, providing safe spaces to those in need and making the veterinary profession more welcoming.

“I was talking to a farmer the other day and he said ‘ I hate it when people say that farming has racism and homophobic issues’ and he said farmers aren't racist or homophobic,” he said.

“And I said, no, but you need to ask the people from those marginalised communities, 'is it racist or homophobic?'

“You shouldn't be telling us because you'll never feel what racism feels like or what, homophobia feels like, or sexism, you know?

“People see the world through their own eyes and they don't understand how we see the world and we need to respect that.”

Photo by Creab Mcselvin on Unsplash

Photo by Creab Mcselvin on Unsplash

Photo by Gayatri Malhotra on Unsplash

Photo by Gayatri Malhotra on Unsplash

"I was refused work because of the colour of my skin"

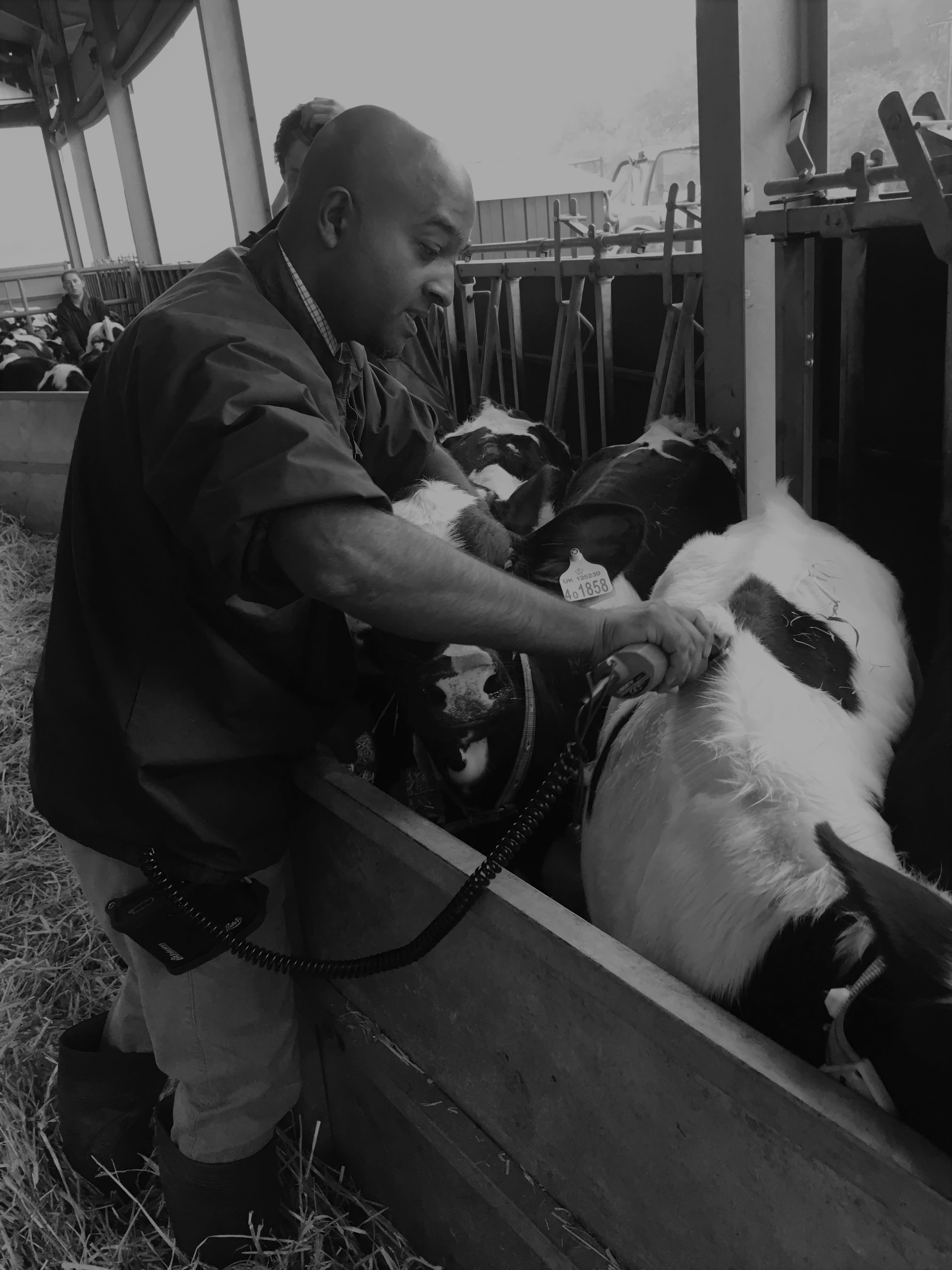

Photo by Navaratnam Partheeban

Photo by Navaratnam Partheeban

"A farmer refused to have me because of the colour of my skin” says Navaratnam Partheeban, a veterinarian and co-founder of the British Veterinary Ethnicity & Diversity Society (BVEDS).

"I went to my bosses and they would support me. I went to the regulatory body and they wouldn't support me. My Association wouldn't support me. I went to a mental health charity, but they wouldn't support me. There was no one to support me.

"This needed to be changed."

Mr Partheeban had always grown up in predominantly white areas.

And when he ventured into a career in farming and veterinary, things were no different for him.

“When I was living in Scotland and Yorkshire I was always the only one like me”, he said.

“My parents tried to make me not understand my own identity to try to fit in.

“When you go into wanting to be a vet, there are no role models like me. I didn't have anybody to look up to. I just said I'm going to try on my own and see what happens.”

Black, Asian and minority ethnicities (BAME) make up a total of only 3% of the veterinary workforce in the UK (BVEDS).

And whilst being the minority, Mr Partheeban would often find himself in discomforting situations.

“At veterinary school, what you want to do is just pass the degree. You'll hear things and be in uncomfortable situations but your ultimate aim is I just wanna finish my degree and become a vet”, he said.

Photo by Navaratnam Partheeban

Photo by Navaratnam Partheeban

“You go through it and put up with it. And when you qualify you just want to be the best vet you can be. You have to go up the ladder, you have to get a job, and you don't wanna be seen as trouble.

“You put up with any negative experiences,” he said.

But after seven years of being a qualified veterinarian, Mr Partheeban faced an encounter that would lead him to no longer stay silent on the racism.

“A farmer refused to have me because of the colour of my skin and I thought, 'I'm confident in my veterinary abilities, I'm confident as a person now I can call this out and say this is wrong,'' he said.

“Six months after I left the clinical practice I thought, now I'm outside, I'm gonna make a change,” he said.

Photo by Navaratnam Partheeban

Photo by Navaratnam Partheeban

“For two years, I tried to do it on my own. I even went back and said, look, this is wrong. You're all wrong.”

After years of persistent trying, Mr Partheeban found himself in contact with an old colleague who, like himself, experienced discirmination.

Together they would join forces to create a group to provide both emotional and educational support to those in similiar positions.

“My colleague, whom I studied with for about 10 years previously, was talking about some of the sexism and racism that she was facing. I just contacted her, and said we're both facing situations. Let's work together.

“We spoke on the phone, and we created BVEDS that day.”

Watch below to hear Mr Partheeban discuss the struggles of veterinary professionals seeking help for discrimination and racism.

Why is diversity key in farming?

One might ask, and rightfully so, why does diversity matter so much in farming?

Although we are not all born to cultivate the land, access to farming should not remain a privilege for the few.

As well as this, many benefits come from diversifying crops on farms - from breaking insect and disease cycles, to reducing weeds, as well as helping improve soil structure.

Yet the same principle is not often applied outside of crops, despite the mounting benefits.

"We need really diverse soils to grow healthy crops, we can't just eat one crop," explains Mr Partheeban.

"We need to get a diversity of crops to keep us healthy. And when we have cows, depending on where they live, whether in the Sahara or in the Elks, we need different breeds.

“Most farmers come from a place where they have no diversity and the only diversity they see on tv.

“They probably think all black and brown people have come across in boats. And we’re either involved in gang violence or we're terrorists.

“They believe these biases are true so we really need to break those biases.”

Read below as Mr Partheeban explains the benefits to diversity within farming.

Benefits to diversity in farming

Photo by Boxed Water Is Better on Unsplash

Photo by Boxed Water Is Better on Unsplash

Feel proud of British culture

“The population of Black people in the UK is bigger than Scotland, and Wales combined. Yet if you put a group of farmers together, I bet there are more Scottish and Welsh people in that room than there are Black people," said Mr Partheeban.

“ As an industry, we should be involving them so that people in Britain value British agriculture. Because why would you wanna buy British?"

He added: “What do we associate with British culture? Do we care if we eat New Zealand lamb or British Lamb? No. It's the same to us.”

“But if there's someone that goes, ‘there are people like me working there’, then you’ll feel buying British would be important to you.”

Photo by Christina @ wocintechchat.com on Unsplash

Photo by Christina @ wocintechchat.com on Unsplash

Commercial advantage

"Farming needs people of colour because it needs talent and diversity," said Mr Partheeban.

“With Amazon and Nike, if you look at their top management, they've got the most diverse boards in the world, hence why they're so good. "

Photo by Anthony Tran on Unsplash

Photo by Anthony Tran on Unsplash

Beneficial for Mental Health

“The worst profession for mental health is veterinary. The worst sector is agriculture for mental health and suicide”, said Mr Partheeban.

92% of UK farmers under the age of 40 ranked poor mental health as the biggest hidden problem facing farmers today revealed in a study by the Farm Safety Foundation.

“Diversity and inclusion should be part of that story. So we need to think about that as a positive way of helping reduce mental health issues," said Mr Partheeban.

Photo by Gradikaa Aggi on Unsplash

Photo by Gradikaa Aggi on Unsplash

Ethnic minorities are big consumers

“4% of the population in the UK is Muslim. 25% of all the sheep meat in this country is eaten by Muslims. So if Muslims tomorrow stopped eating British lamb, the whole sheep industry would collapse," said Mr Partheeban.

“Farmers know more about Islam than probably most of the country put together because they need to know about it.”

He added: “Having those people as part of farming helps with that business because we're changing and we're evolving as a country.”

Muslims and Farming

Photo by Muhsen Hassanin

Photo by Muhsen Hassanin

Land has got to be accessible to the community, especially to inner city Muslim kids, says Muhsen Hassanin, a British Muslim farmer.

Muhsen Hassanin, who left his marketing job in London 10 years ago to buy a farm in the Welsh Valleys, says his main goal is to inspire other Muslims to move to outer rural lands.

“The vision when I got here was that this needs to be for the community. It needs to be something that we share. We can't just become landlords and landowners and join that class of people.

“It's gotta be accessible for the community, especially for inner city, Muslim kids, that's my main goal that I want to achieve,” he said.

Before his move to the Welsh Valleys, Mr Hassanin had worked as a face to face fundraiser in London.

Photo by Muhsen Hassanin

Photo by Muhsen Hassanin

In 2013, he left his job and soon began studying permaculture, a design science, which drew him more to want to own a farm of his own.

“I started studying permaculture and I got really interested in food and health and that kind of drew me towards that life. So then, the vision became a farm."

Soon after, Mr Hassanin made the life changing decision and moved his entire family, including his wife, kids and mum, onto the farm.

“It was an exciting time because it was a blank canvas and I could see there was so much potential. It’s not everything that I wanted it to be but we’ve done so much already in the time we’ve been here.”

Photo by Muhsen Hassanin

Photo by Muhsen Hassanin

Now he hosts a variety of animals, including cows, goats and chickens which his family tend now.

Mr Hassanin is just one of very few non-white and Muslim farmers in the UK.

He says many inner city Muslims may be scared to make a move to farm lands as they do not see the appeal.

“The first generation of Muslims that came to the UK worked very hard. They worked in factories and many other labour jobs to build up their wealth, which then allowed their children to be doctors and lawyers and solicitors and many other high level professions,” he said.

“But because of this, there's this idea of why would you want to go back to living how we lived? We left that life for you to have a comfortable life and now you want to be uncomfortable again?

“I labelled myself British Muslim Farmer because I want it to be a symbol of what can be achieved.

“For me, it's not even just about farming this, it's about the courage and I’m now like a symbol for somebody doing something that is normally done within the community here.”

“I would love it to be inspiring for many more British Muslim farmers to come definitely and even if we don't become farmers, I want us to connect with the farmers and make sure that we understand how our food is grown and respect the farmers and show them our support by buying direct.”

Watch below to hear Mr Hassanin discuss the positives and negatives of moving to the countryside.

Solutions to the issues

"I’ve thought long and hard as to whether I've ever experienced any form of prejudice or discrimination and the truth is I haven’t.”

“I've never encountered a glass ceiling, I've never felt excluded from conversations in any way and throughout my life, all doors have been open to me."

This is what Welsh farmer and chairman of the Oxford Farming Conference (OFC), Will Evans, said during his speech at the annual conference in 2020.

It's a hard truth that some white farmers fail to come to terms with, but one Mr Evans has accepted.

And a truth he is trying to teach others.

“Farmers should know more than anybody about the importance of diversity because we need diverse crops, diverse income streams, diversity is good in everything so why wouldn't it be good for people as well?,” he said.

“It's just so blindly obvious.

“More middle-aged white dudes like me need to have these conversations more.

“Farmers, by their very nature, often live in quite remote areas, a long way from urban centres.

“They aren't exposed to people from different backgrounds and different races and religions but social media has helped that to an extent.”

“We’ve still got an awfully long way to go but I am encouraged that I am seeing more people talk about these issues and 99% of these conversations are positive.”

Mr Evans says he didn't always grow up with diversity around him.

But working in a diverse team has taught him more than ever the huge benefits of not only implementing diversity on farms but within the workforce.

“I'm from a small family farm in Wales. It’s me, my mom and dad, and we have occasional help in the summer when we're busy harvesting,” he said.

“We're a fairly diverse family farm, but from a human level, I hadn't been exposed to diversity.

“But working on the OFC board of directors and working with quite a big diverse team, it's been such an eye opener.

“[Diversity] brings such a fresh perspective. Your eyes are open to new ideas and different things that you'd never even thought of before.

“I've seen what a diverse group of people can do together and they can do so much more than a group of people who are all the same age, from the same background and same skin colour and sexuality.”

Will Evans at the 2023 Oxford Farming Conference

Mr Evans has been working to put diversity at the forefront of OFC conferences and made the decision to use diversity as the theme of the 2023 conference, a choice he says was welcomed by the whole board.

“I was on the tractor one day, which is where I do all my thinking, and I thought, ‘why don't we make the whole conference theme about diversity?’ We'll call it the power of diversity,” he said.

“When I came up with that idea, every single one of the people on the board thought it was a great idea. They were all unanimously behind it.

“I hope that we can make a difference with it and do something that we can all be proud of.”

Racism and discrimination within farming is far from over and there is certainly still a long way to go.

If farming is to become more diverse and inclusive, then those who hold the power need to acknowledge their errors and be accountable to better management.

But hope remains and as long as conversations like these continue to happen and with the minds of people like Wilfred Emmanuel Jones, Navaratnam Partheeban and Will Evans, changes will begin to happen sooner than later.

Take the quiz below to find out if you've been focusing

Image credits

Field of sheep: By Florence Freeman

White Farmer: By Unsplash