Fighting for a lost home

Afghan diaspora protests starving Afghanistan

Afghanistan since 15 august

Afghanistan, one of the poorest economies in Asia, is on the brink of a humanitarian crisis.

On the same day Kabul fell, the Taliban declared the restoration of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan—a return to the 1996 to 2001 government.

After a chaotic 15 day evacuation of military and diplomatic personnel and refugees, the US military departed Afghanistan on 30 August.

The Taliban swiftly took control of the rest of Afghanistan, and by 6 September, had captured the historically anti-Taliban Panjshir Valley.

Panjshir successfully resisted Soviet occupation in the eighties and attacks from the Taliban in the nineties.

There are reports of resistance forces fighting with the Taliban recently, but it is believed the group lacks leadership and external support.

The Taliban takeover has turned Afghanistan into a global pariah.

At the time of writing, no country has formally recognised the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan.

Isolation is particularly difficult for Afghanistan as, according to a 2020 IMF report, foreign aid accounted for 40% of GDP.

Foreign aid was also a crucial source of money for the government, in 2019 75% of the Ministry of Finances' budget came from international grants.

Shortly after the fall, the US imposed strict sanctions on Afghanistan, freezing nearly $10 billion Afghan central bank assets and restricting access to international funding.

The successes of the Taliban mean the loss of hard-won rights for Afghan women.

Girls were excluded from returning to secondary schools when they reopened in September.

Private universities must be segregated by sex and the government even asked working women to stay at home.

When the Taliban government told boys to return to secondary school, girls were excluded from returning.

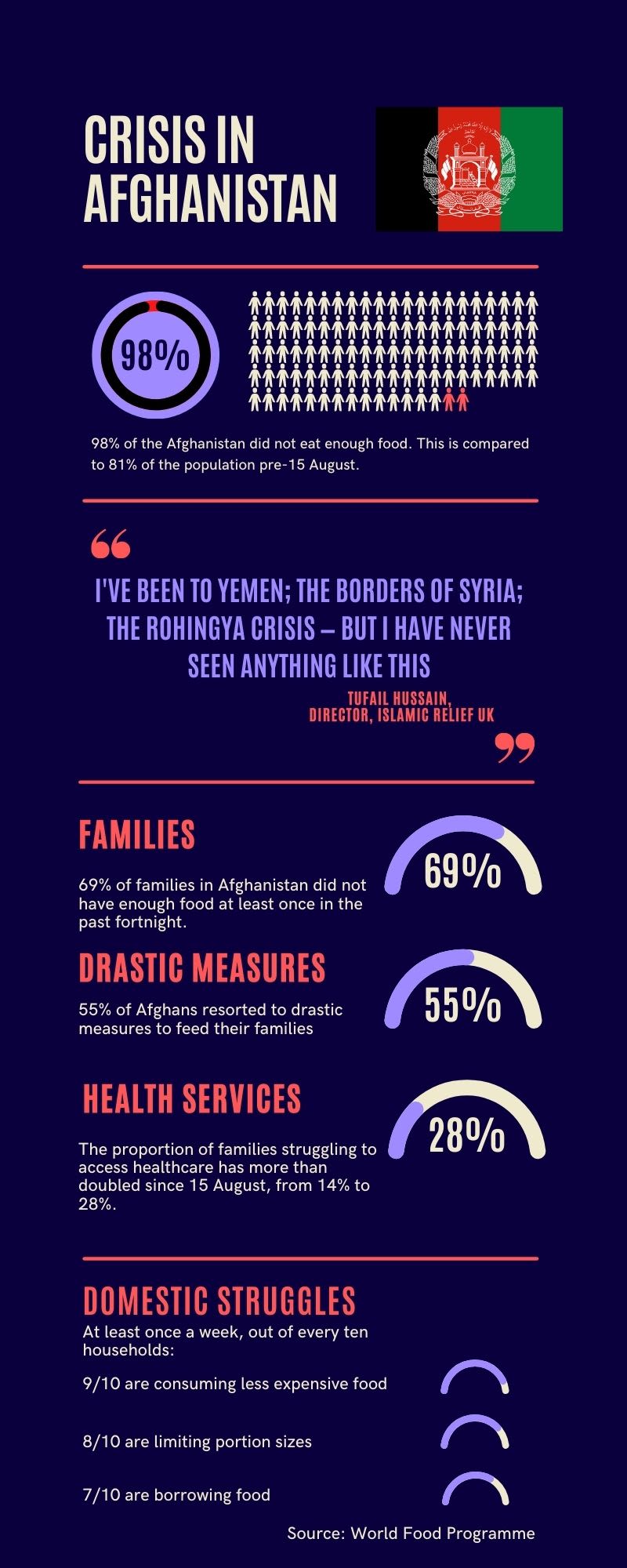

Before the Taliban takeover, 11 million Afghanis were food insecure because of drought, conflict and COVID-19.

According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), the country is facing its second drought in four years and the worst of its kind for 27 years.

The United Nations Development Programme commented that Afghanistan’s economy has seen a more severe decline in the last few months than Syria’s economy saw in the first five years of civil war.

In a recent report, the World Food Programme (WFP) warned that 22.8 million people, half the population, will suffer from acute food insecurity—3.2 million of which are children.

8.7 million people are currently at risk of famine-like conditions, 1 million of which are children.

According to the WFP, 98% of Afghans are suffering from a lack of food compared to 81% pre-August 15.

The US and UN recently loosened their stance on restrictions to allow relief organisations to distribute aid within Afghanistan.

It remains to be seen whether this move will be enough to prevent catastrophe.

The Afghan diaspora, people from the country who live abroad, have watched this unfold despite their public protests.

Gordon Brown on Afghanistan

Former Prime Minister Gordon Brown spoke about the West's moral responsibility for Afghanistan on BBC Radio 4's Today programme on 29 December.

“The failure to exit in an orderly way has created many of these problems we are now facing," Brown said.

"But we would be facing these problems if we did not, as we are failing to do, provide humanitarian aid.”

The former PM explained that 23 million people will be unable to feed themselves this winter, with 97% of the population expected to be in poverty—the worst rate in the world.

Brown highlighted three things that can be done to help ease the immediate humanitarian crisis.

Firstly, that the world bank needs to get humanitarian cash into organisations like the World Food Programme and Unicef to support the people of Afghanistan.

Secondly, that support is given to informal NGOs working in Afghanistan.

Thirdly, using Qatar and the Islamic Development Bank to bypass the Taliban, the international community should get money and supplies into Afghanistan.

He said: “Otherwise we will see mass emigration from Afghanistan and at the same time we will see resentments building and terrorists will exploit this by telling young people you cannot co-exist with the west.

“So we’ve got to act for moral reasons, but it is in our self-interest to do so.”

Brown thought that there should be a pledging conference, which he felt Britain could lead, to raise the necessary four and a half billion to ease the humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan.

He added: “We spent a thousand billion on the war in Afghanistan—well, the Americans did—four billion is a very small fraction of that and that is money to prevent starvation this winter.

“Because that is what we’re talking about: people being starved to death, malnutrition stalking the land and disease as people are denied proper healthcare.

“We are in an integrated and interconnected world where we are all affected by decisions that are made in other countries and we have got to do something to help those, particularly those who face starvation.

“Otherwise, not just for moral reasons but for self-interested reasons, this will come back to haunt us.”

'We've got a moral duty to help people who are at risk.'

— LBC (@LBC) December 29, 2021

Gordon Brown speaks to LBC's Ben Kentish about the humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan.@BenKentish | @GordonBrown pic.twitter.com/4FxEBegNnp

Brown speaking to LBC about the humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan.

Background image credit: Julien Daniel/OECD, Flickr, 3 April 2017, CC BY-NC 2.0

Orzullah

Orzullah Majidi organised a protest outside the US embassy in London on 19 December, supporting the #endafghanstarvation protest outside of the White House in Washington DC.

The protest was small but protestors criticised former Afghan leaders living in the UK who were absent from the protest.

#endafghanstarvation is a campaign created by the Afghan diaspora in America and Europe to protest the deteriorating humanitarian situation in Afghanistan.

“Since the start of this crisis, in July, my main concern has been the humanitarian situation,” Orzullah said.

“Right now, Afghanistan is headed towards mass starvation—probably the largest the world has seen in a hundred years.”

Orzullah is Afghan-American but lives in London with her family, and has worked as an advisor to the Afghan government for 11 years.

She said: “I am a mother of two little girls, it’s the holiday season, and they walk by and they see gingerbread men and other things.

“When kids don’t get what they want, sometimes they cry and when I hear my kids cry, I hear a million children crying.

“I cannot imagine what it’s like to be a mother in Afghanistan right now, how must they feel when they can’t feed their children?

“We can do something to ease the suffering of these innocent people.”

Orzullah explained that there were transparent mechanisms and organisations, like Islamic Relief, that could provide aid to Afghanistan without supporting the Taliban.

She said: “Food is a basic human right, a basic human need and right now Afghan people are not getting the basics.

“I grew up in the 80s and I remember the ‘Heal the World’ song, and now it is happening again.

“History shows that intervention is needed in crises like this: we always look back at this large humanitarian crises and say never again, but they keep happening.

“When will we finally say enough?”

Family still in Afghanistan is a source of constant anxiety and concern for Orzullah and other members of the Afghan diaspora.

She detailed bleak accounts of children being left at hospitals and mosques because their families cannot feed them.

“It’s desperate: there is no way for people to access money, everything has collapsed inside the country—it’s very difficult to send money into the country,” Orzullah said.

A large-scale aid operation to distribute aid equally throughout Afghanistan before the first snowfalls was Orzullah's main demand.

The WFP situation report from December 8 already mentions disruption linked to snowfall.

She added: “Afghans love snow, so it was bittersweet for us to see the first snowfall on this occasion.

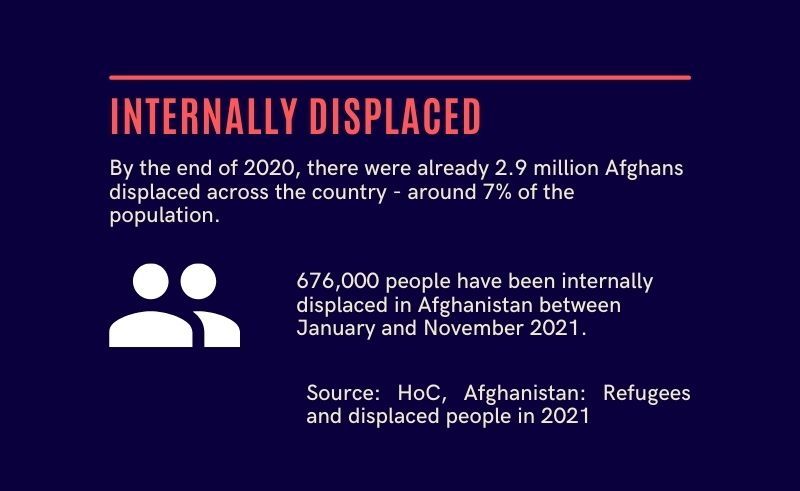

“There have been a lot of Afghans displaced internally—imagine millions of rough sleepers out in the snow.

“Sometimes I feel overwhelmed with a sense of hopelessness, but I channel that into activism.

“Even in that pain, despair and sadness I cannot give up—millions depend on us not giving up.”

The #endafghanstarvation petition can be signed here.

Sodaba

Sodaba lives in London but is from Afghanistan and still has family in the country.

Sodaba did not wish to give her full name.

“I just came to raise my voice for our people’s lives because now Afghan people need food and are lacking basic human rights like a career and education,” Sodaba said.

“I believe it will be a tragic time for our people, it will be the biggest crisis of the 21st century.

“They are in a very bad situation: people were selling their kids but now they are leaving them at hospitals and mosques.

“I request for the international community to provide Afghanistan with peace and food.”

Sodaba felt it was important to attend the protest because it meant being able to stand for Afghan voices silenced by the Taliban.

She said: “We need to push governments, especially American and Britain, to do more for Afghanistan.

“The Afghan economy has completely collapsed—in a few months millions of people will be on the edge of starvation and death.

“I live in London, but my soul is in Afghanistan.”

She was candid about the mental health struggle brought on by the crisis, mentioning that she struggled to motivate herself and her children to eat.

Sodaba said: “The diaspora is really depressed, we can see that there will be no quick solution for this issue and we see Afghanistan suffer.

“Many in the diaspora are hopeless about Afghanistan because it all happened so suddenly and we were shocked."

Sodaba described the almost instantaneous feeling of grief at watching the Islamic Republic collapse, knowing that it foreclosed a bright future for many Afghan girls.

“Sometimes, I think when I see my children going to school I feel really bad, I think of my country and my people: the girls and women are sitting at home, even if they have a high level of education.”

Despite feeling hopeless, Sodaba explained that she channelled her emotions into her activism.

She said: “If we are united and build connections inside and outside the diaspora, we can build power and influence enough to help Afghanistan.

“I hope to see a bright future, with a high level of education, because I know that without education we cannot succeed.

“I can see in the eyes of the future generation a pure, pure diamond.

“We are from different nations, but we are a strong Afghanistan.”