Forced to flee: The human side of warfare

A total of 37,218 Afghans – many of them allies of the British armed forces - have moved to the UK since 2021. But why did they leave and how have they settled into UK life?

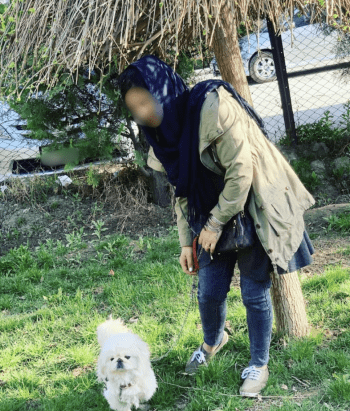

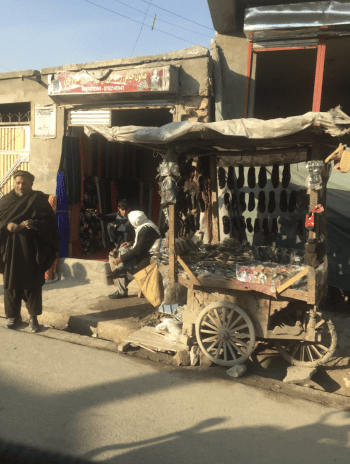

Afghanistan was once a country that embraced modernisation. Women were seen as equals, bustling cafes were a hub of social activity and tourism was booming.

Credit: William Podlich

Credit: William Podlich

Credit: William Podlich

Credit: William Podlich

Credit: William Podlich

Credit: William Podlich

46,000

Now, women are restricted, neighbours are spies and many have been forced to flee their home.

Over 46,000 civilians from 2001 -2021 were killed during the war in Afghanistan, according to the Costs of War Project. Many more have been killed since the Taliban regained control.

Noor's story

"The Taliban put a bomb under his car and it exploded. He lost both of his feet."

Noor* fled to the UK three years ago after the Taliban targeted her husband.

With a steady voice, Noor recounts the day her husband, who worked as an interpreter for the British Army, faced the regime.

“There was a fight and one of the British soldiers was killed, but his body was just left there," she said.

"The Taliban were shouting on the loud speaker to leave the body, but my husband said the soldier came here to save us, and the least we can do is give his family his body back.

“He pulled him in and they sent the body back to the UK.

"Later, when he went out shopping, the Taliban put a bomb under his car and it exploded.

“He lost both of his feet.”

The young family were faced with a decision. Stay and risk being targeted, or leave and drop all of their possessions, family, friends, home.

Noor did not want to leave. It took three months to convince her it was the right decision.

Her mother pleaded with her to go, to save her children and to protect herself. Noor retold the moment her mother approached her, pleading, “Please daughter, you must leave. I know you don’t want to be far from me but I don’t want anything to happen to you or your children.”

It was then that Noor, pregnant and defeated, decided to leave.

Escaping in an American cargo plane with two young daughters and a baby on the way, Noor was shaken.

“We had a life like royalty in Afghanistan,” she shares. “I had a really lovely house that I built myself. I had a good salary and position in society. I had my friends around and my mum was with me all the time. I had a really good life.”

In Afghanistan, Noor was university educated and was the director of a charity in the Badakhshan province for 10 years. Her role focused on helping Afghans, particularly women and children, providing food, education and medical aid.

As she lived in the northern provinces, it was more difficult for women to access services provided in the cities such as hospitals and so she served the community through the charity, using her wealth and status to support them.

“The crucial difference is that we had to leave. It’s not that we chose to go somewhere for a holiday or vacation. It was a change of life. ‘Had’ means no choice.”

Noor shared there was a lack of choice she faced when she needed to relocate for her safety, stressing that it was not a move she wanted to make.

After media reports of Afghans returning for holiday’s, posting their trip on their social media, Noor wanted to reinforce that for most Afghan immigrants, it is not like this. “The crucial difference is that we had to leave. It’s not that we chose to go somewhere for a holiday or vacation. It was a change of life. ‘Had’ means no choice.”

From language and community, to weather and social standing, it was completely alien. “It was the second country I had ever travelled to and everything was completely different, even the weather.”

“My husband started as a cleaner but it was painful. He came back from work every day and didn’t even want food, he just wanted to sit because his feet were so sore from his injuries," she explains.

She continues, "I have to work but I like to work. I don’t want to stay on benefits. I want to work and contribute, pay tax to the country. I can confidently say that most Afghans want to have their own income and don’t want to rely on other people.

"Now we are both settled and happy. We have our children in school and nurseries. We are really happy with the service and activity we receive from the UK government and all the charities that help refugees.”

Noor and her family now live in the north west of England, where they are the only Afghans in the area. She shares her positive experience moving to the UK and the warm welcome they received.

She says, smiling, "My neighbours have been so lovely and my children call them Grandma and Grandpa. I don’t have any complaints, I am happy. I always appreciate the opportunity the government gave me to move here.”

Despite being relocated for their safety, many of the Afghan immigrants have family still in Afghanistan, unable to leave.

Noor shares that their family are still in Afghanistan, trapped by the Taliban.

Sad, but accepting, Noor says, "Because my husband's identity is known by the Taliban, our family have to move all the time. They are looking for them."

Her families’ safety is a constant undercurrent of worry. But there is nothing she can do to help them. With the tightening of restrictions as well as new immigration laws, it is now near impossible to move them to the UK.

When asked if her family will ever escape, she sighs. "No, they cannot ever leave. It is too difficult.”

Noor works for the Sulha Alliance. The organisation supports interpreters and Afghans who worked alongside the British Army in Afghanistan.

Noor said, “One of the ladies that came to us was the wife of an interpreter, but he died here and so she was alone. We provided lots of support for her. This is what we do for families in need.

"We, the Solar Alliance, find jobs for them when they have problems. My job before as a chairperson in Afghanistan was helping people.

"So helping is my hobby. And I'm really happy that I'm in a position where I can help.”

With the Sulha Alliance, Noor started the Afghan Kitchen in late 2023. She believes the pillars of hospitality that uphold Afghan culture are vital for a community.

“We are always happy to share our food and believe when someone eats our food he or she will be kind to us and respect us. It is a deeply ingrained value that shapes how people interact and builds trust.

"When someone comes to our house and goes without any food we will be really unhappy and sad, but if someone eats our food and likes it we will appreciate it very much and make us happy.

"I'm also helping other Afghan women in my community who face the same language barriers and integration challenges I once faced.

"My children are really happy, they have friends here. I am friends with both Afghan and English people locally, and I feel joy when I'm at home, or at work, or out and about in the community.”

37,218

The Government ended the Afghan Relocations and Assistance Policy to new applications on 1 July 2025. The scheme, designed to help Afghans who had worked with the British Armed Forces during the conflict, resettled 21,316 people from its launch in April 2021.

Around 37,218 individuals were recorded in the official Afghan ARAP and ACRS schemes by late 2025. Another source indicates around 38,700 had been resettled as of July 2025.

Many are in full time employment and contributing to society.

Credit: Jeremy Pughe-Morgan

Credit: Jeremy Pughe-Morgan

Credit: Jeremy Pughe-Morgan

Credit: Jeremy Pughe-Morgan

Credit: Jeremy Pughe-Morgan

Credit: Jeremy Pughe-Morgan

Maryam's

story

"We deserve the chance to live with dignity, to find happiness again, and to ensure that our children grow up safe and secure."

Maryam* had a similar story. She worked for the Halo Trust in Afghanistan, a mine clearing organisation, working as the gender equality officer.

However, her husband’s work as an interpreter also led her to being forced to leave and relocate to the UK.

Maryam is strong, determined. She is rebuilding her life here and is fiercely protective of others who are too.

But she tells me it still hurts to speak about what she has been through.

She shares,“We all came here, missing our families, friends, and home. One day you have a job, home, family and the next day you wake up and it's all gone and you’re in a new country, new people, new language and it’s hard.

"You need to experience that to understand it."

She continues, "When people ask whether we are 'enjoying' what we have received in the UK, they misunderstand our reality. The truth is quite the opposite."

Maryam fled the Taliban in November 2021, with the help of the owner of a safe house they were staying at.

After landing in the UK, she has since joined various organisations that support Afghans. Her motivation? "We are suffering," she says.

Shortly after arriving, a neighbour approached Maryam to ask how she was settling in. She replied by asking them to imagine their own life instead; waking up one morning to find everything you have build has vanished: your country, your family and friends, you career, your home, your plans for the future.

"I even had to leave my pet behind," she says, "a part of my daily life that I could not take with me.

"Imagine having no choice but to leave all of this overnight. How would you feel?"

Maryam says, "Coming to the UK was never a choice for us. We came to survive. I believe anyone in our position would have done the same."

Many immigrants have experienced deep depression. They miss their families, friends, colleagues, neighbours. Some had no chance to say goodbye to their loved ones at all.

"Life is extremely hard for us, but we endure because we must.

"We are rebuilding our lives from nothing in a new country, and that is not easy. We ask only for understanding and support, not judgement or added hardship.

"We deserve the chance to live with dignity, to find happiness again, and to ensure that our children grow up safe and secure."

"The first time, we ignored it. The second time, my father in law was shot. That’s when we realised our situation was no longer safe.”

Maryam’s situation changed overnight when her family received a threat from the Taliban.

“When my husband worked with the British army, we received a threat from the Taliban.

"The first time, we ignored it. The second time, my father in law was shot. That’s when we realised our situation was no longer safe.”

Neighbour turned on neighbour. No one knew who to trust.

“The Taliban hate those who work with the British more than the British themselves," she says.

"We never knew who was on the Taliban’s side. It could have been any of our neighbours. They had eyes on us all the time. That's why we had to leave," she says.

On arriving in the UK, Maryam explained she also experienced a positive welcome.

She says, “We will never forget those smiley faces when we landed in the UK. I still have that in my mind. Them, standing there as we came off the plane. I love it.

“I appreciate that because those were the faces we needed to see after landing in a new country. I really appreciate everything they did, but I'm also saying that there is still a lot to do.

"Let's try some positivity so the government will understand that we are going to be a good asset for them,"

She ends, “When I first came here, I was proud to say I came under the Afghan scheme and my husband was working with the British Forces. It was great, and people were treating us well but now it's changed because of the negative media.”

Amir's story

Armed with guns, still at the front door of his home, they threatened him.

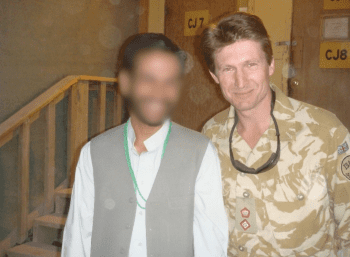

Amir worked with the British Armed Forces as an interpreter before moving to the UK for his families’ safety.

A village divided. Neighbour on neighbour. Fear is in control.

Amir explains his village was split into two tribes: one that supported the Taliban regime, and one that didn't.

"The supporters were always telling us that our time will come and then they will attack.”

Then one day, they did.

Calmly, Amir recounts the events that took place after his evacuation. The stress would have been unbearable, but he remains steady as he explains what happened.

"The Taliban fighters knocked on our door as my father was leaving to go to the mosque, and asked about me.

"My father is a farmer so is an uneducated, old man, but a very kind person. He told them that I was in a neighbouring country working as a labourer."

They laughed. "No, he is not."

Armed with guns, still at the front door of his home, they threatened him: "We know where he is but lucky for you, he’s not here right now.”

Amir says the villagers, whether Pashtun, Tajik or Azara, all have relatives or friends working in the government.

This creates a web of spies, allowing the Taliban to find and target anyone who had worked with the British Army far too easily.

“They knew that you were working with them, what you were doing, where you lived, where your family were," Amir said.

"What happened was something that was out of our control."

Amir explained signing up to work with the British Army was a choice, and one he does not regret.

Proudly, Amir says,“The British people were struggling with the language and were not able to deliver their message without interpreters, so I found myself thinking that I was the right person to deliver that service.

“My approach was that the coalition forces were here and we were going to rebuild this country together.

"Being an interpreter was the least I could do to help.

"We were building schools, bridges, hospitals which were all contributing towards the country.

"We wanted to build the Afghan government, army and police institutions but what happened was something that was out of our control."

He continues, "The world leaders decided to leave the country and hand it back to those that we were fighting against."

Without interpreters, the British and American troops deployed in Afghanistan could have walked into situations unaware of the dangers that lay ahead.

Only an Afghan who understood the culture and spoke the language could inform them, keep them safe.

“We were part of a family," Amir says, "And when I think of those times we worked together and the dangers we faced, I am shocked we are all still alive. You never forget the people who endured those tough times with you.

“We were everything for each other on the front line."

“Honestly speaking, if we were left behind, the majority of us would not be alive today"

Amir reminds me, because of this choice, he paved his own way for exposure and security concerns.

“Interpreters chose the British as their own allies knowing that if they fled the country and weren’t there to interpret anymore, catastrophic things would happen to these people they were working with shoulder to shoulder.

"Those who worked alongside NATO allies do not see a future in Afghanistan anymore. They are back to square one," he says.

Amir seems defeated, knowing he can never return to his home.

“Honestly speaking, if we were left behind, the majority of us would not be alive today," he ends.

Amir is proud of his work, proud of his contribution and endlessly grateful to the British Army for what they did in Afghanistan.

"I am grateful to the UK government and to the British people who have provided for us," he says. "That is something we will never be able to forget and as Afghans we will always be grateful for what we have received.

"I do believe that we wouldn’t be in this world if we were not taken in by the UK.”

As with many Afghans, Amir suffered from PTSD and depression on arriving to the UK. The weight of knowing he had to leave his family behind, known to the Taliban and in danger, was too heavy. “I was safe and felt safe, but I was still worried about my family back in Afghanistan," he says.

Discussing his plans for returning to his home, Amir relays the same response. “I won’t be able to return because I don’t find myself there anymore," he says.

"It’s my country, it's where I grew up, but the sad truth is that because of my work, they don’t think I should be there anymore.

"The Taliban say that the power is in their hands now and they will do whatever they want," he says.

With the new restrictions, and rising anti-immigration stances, Amir worries for his future in the UK. “We received indefinite leave to remain in the UK and they even said I could apply for British citizenship, but I don’t know if they will consider us anymore after these new regulations.

"They might take it away and I will be sent back to Afghanistan," he says.

Amir has started his own organisation to help Afghans integrate, National Integration Hub, with a simple aim; “I want to empower those who struggle, as you cannot let them struggle forever - they have to be uplifted and trained. So skills and experience should be provided to motivate them.”

He continues, “I want to work hard and see where the problem lies so I can find solutions and contribute to the community."

Amir supports his wife and three young children, one born only recently. I can hear his children in the background of the call, and sense the pride in his voice when he talks of his wife's achievements since moving to the UK.

He beams, “My plan is to set up a family business for my wife to run so once she has finished looking after the children then she has an opportunity to work.

"She was forced to stop school at 10 or 12 and so she is now pursuing college in the UK. Because of the cultural limitations, she could not do that in Afghanistan so she is looking forward to her education now which is fantastic.”

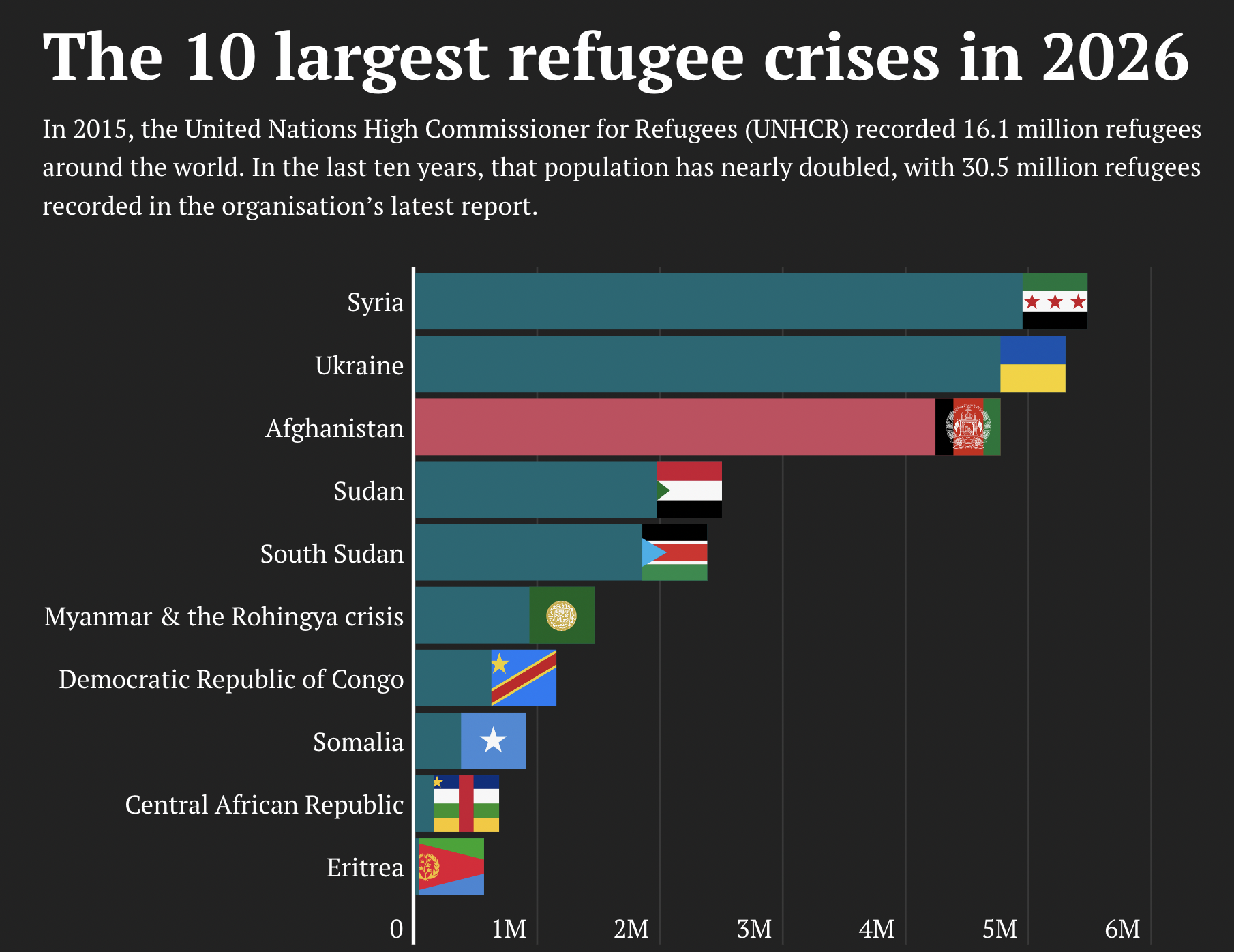

Data taken from: https://www.concern.net/news/largest-refugee-crises

Data taken from: https://www.concern.net/news/largest-refugee-crises

The future

"I was closer to my interpreter than I was to any other person during my tour interview. I trusted him with my life on a daily basis."

Major General Charlie Herbert worked with many Afghan interpreters on multiple tours in Afghanistan during the height of the conflict and before the Taliban swept back to power.

Herbert shares,“I simply could not have done my job without the use of interpreters. They lived with us. They shared our risks. They were absolutely integral to what we did.

"I was closer to my interpreter than I was to any other person during my tour interview. I trusted him with my life on a daily basis.

"He made decisions about situations, cultural context, the atmospherics about a place or a location. He listened in on the radios."

He continues, "They were absolutely wonderful people. They were so hospitable. And that's why I feel so sad, actually, about how inhospitable the UK can be to them."

Major General Herbert shared his experience visiting an old Afghan colleague who was relocated with the MoD schemes back when the Taliban took control again.

"He is such a proud man and such a big, big figure in Afghanistan," he says, "And then I saw him living in a little house in Warwick, a shell of the person he was and can see he was not particularly happy, it just breaks my heart."

Major General Herbert is saddened by the response many Afghans have experienced in the UK. With rising tensions towards immigrants brought on by anti-immigration politics and the rise of Reform UK, many Afghans feel unwanted in their new home.

"I think we owe a debt of honour to them."

The Major General shares, “Afghans are incredibly industrious, incredibly hard working, genuinely good people. They're proud people that don't want to be unemployed.

"I think the real key theme is that many of them don't want to be here.

"Many of them want to be back in Afghanistan. They're not here just to claim benefits and make life crap for the UK.

"And should the Taliban leave, should the situation change, many of them would return, and we should respect that.”

He ends, "I think we owe a debt of honour to them."

The Ministry of Defence were contacted for comment.

Charities

Sulha Alliance

The Sulha Alliance CIO is the only UK charity whose work solely focuses on supporting Afghan interpreters and other Locally Engaged Civilians (LECs), who worked for the British Army. We have successfully campaigned for their protection through resettlement to the UK from Afghanistan and continue to support the community with building their lives in the UK.

In summary, our money is spent on our community officers travelling to support families in person, community engagement events, learning materials for educational purposes (language lessons) and on rare occasions, our hardship fund. The funding for our community support officers also helps pay for that support we give around, housing, education, immigration and accessing healthcare and mental health support.

Community integration social events are paid for by donations that give Afghan families a chance to reconnect and socialise together, get support from our team, and get introduced to the wider local community.

Sara De Jong, Sulha Alliance Co-Founder

National Integration Hub

The National Integration Hub provides a comprehensive, structured framework for the successful settlement and long-term integration of Refugees and Afghans arriving in the UK.

Tackles key challenges in refugee resettlement by collaborating with local partners, businesses, and communities. Their focus is on creating practical, innovative solutions to help every individual thrive, contribute, and achieve a true sense of belonging.

Basheer Ahmad, Founder and Managing Director