HERE YOU'RE A KING

How a contested World Championship captured a snapshot of a little-known sport

Tom Billings is an addict.

Five days previously, Billings competed in the second leg of the World Doubles Championship, a competition which took him and his partner Richard Owen to play in New York. The match was on Saturday, and he flew back to London the next day.

On Monday, he played the first match in the British Amateur Singles.

“I was absolutely knackered. My shoulder – everything – hurts. I have no idea why I thought it was a good idea to play. But I’m playing tomorrow and I’ve got games all week.”

There is no little disbelief in Billings’ voice.

“I think I’ve got problems.”

He is unlikely to find an understanding ear almost anywhere. Only in small corners of a handful of clubs and schools in the UK and North America, is there nothing but sympathy, and fellow sufferers.

The sport is rackets, the affliction likely terminal.

Most people have heard of, if not played, squash. Any rackets player will go to lengths to tell you, emphatically, that rackets is not squash. Squash is its progeny, nothing more than warm-up game which has taken all of its originator’s popularity and recognition.

Almost every player of rackets, in an effort to get an outsider to understand the game, will nevertheless bring up squash.

But rackets is only squash with added chaos, danger, and skill, as two or four players attempt to control a scarcely visible rock-hard ball which can be hit up to 180mph off all four walls of the black and terracotta court. The comparison grows weaker the more a person learns about rackets.

It can be hard to learn. Most of the sport’s supporters have been involved with the game since the age of 12 or 13, and are passionate players, spectators, and benefactors who would do anything to keep the game and its traditions alive. But beyond that small fraternity, rackets is largely unknown.

What does it mean, then, to become its World Champion?

In October 2021, Billings and Owen won the challenge to contest the World Championship against the current titleholders, Jonathan Larken and James Stout. The competition has only been contested since 1990, but it follows in the same traditions as the much older Singles Championship, which the first holder claimed in 1820.

The competition takes place over two legs, and the venues, one in the UK and the other in North America, are chosen by the current World Champions. Each match is best of seven games, and each game the first to 15 points. This makes the lowest number of games the winner has to take is five over both legs: four in the first, and one in the second.

The pairs have met before, the last time the Championship was fought over – 2018 – and Larken and Stout held onto the title they first won in 2016 by delivering that fatal scoreline.

“Incredibly demoralising,” Billings says of the format.

The pain comes from thinking that qualification to play is enough, that you have a chance, Billings says, only to find out, abruptly, you don’t.

“But actually on the day, it’s quite liberating. All that pressure that you felt in that first leg, and all the stresses of playing, it goes away.”

Billings is meditative and sincere: one of few that can be relied upon to find the chink of light in a black situation. That strength of character, as well as rare talent, has delivered him a World Championship of his own, winning the Singles in 2019.

Having first started playing at Haileybury School 17 years ago, rackets is as commonplace now to Billings as brushing his teeth. The pandemic represented the first break he had from the sport in as long as he can remember, as he stopped for four months with the rest of the world.

As a player, his achievements represent the peak of an amateur rackets career. The opportunity to combine the two world titles is rare. But it has been done before, first in 1991 by James Male, and in 2017, by Billings’ opponent, James Stout.

James Stout is one of the greatest players to have played the game. Singles World Champion from 2008 until his retirement from singles in 2019, he has also played professional squash, representing Bermuda at the Commonwealth Games and the Men’s World Open Squash Championships.

Unlike Billings, Stout is a professional, working at the New York Racquet and Tennis Club. The top competitions in the sport, World Championships and the British and Western Opens, are open to both amateurs and professionals, but there’s no presumption that the professional should win, unless that professional is Stout.

"I came along, from squash, and I’d been used to proper training, living and breathing the sport. I don’t think for the most part, there had been someone that had put that sort of time and effort into training that I’d done.

“I could run longer than anyone, I could last longer on court than anyone. For most amateurs, the time constraints are there, you can’t spend three, four hours a day on court, which is a big advantage for me.“

Stout retired from the singles game because by then, having been World Champion for 10 years and won everything he could, he was mainly playing himself.

“Winning the World Championship 5-0 was never my goal. My goal was to win the World Championship without giving up 15 points.

“I got to a point where I wasn’t playing to the standard that I thought I should be playing. I was like, ‘do I want to lose a match, because my head’s just not there? Do I want to play at a standard that I think is below me?’ And the answer was no. So it ended up being a much simpler decision than it felt.”

Doubles still scratches an itch which singles doesn’t, largely due to the partnership dynamic. Enough to defend the title he and Larken share, at least.

Tom Billings, 28, is seeking to emulate the titanic career of his opponent, James Stout, 37. Credit: Tamara Prenn

‘“It strikes me, Sam,’ said Mr. Pickwick, leaning over the iron rail at the stair-head, ‘it strikes me, Sam, that imprisonment for debt is scarcely any punishment at all.”’

- Charles Dickens, The Pickwick Papers

The contemporary game’s association with elitism – the Championship venues in Manhattan and southwest London, its public school competitors, a champagne sponsor (Pol Roger) – belies its grubbier origins. The sport was first played at two London debtors’ prisons in the mid-18th century, the King’s Bench, and Fleet Prison.

But even these settings had a comparatively glamorous tinge, according to Dr Alexander Wakelam.

Dr Wakelam, a historian specialising in the history of debt and insolvency, added: “There’s a significant number of people there would be described as petty aristocracy.

“The kind of man who lives off income without having to work – around 15% of people in the Fleet are coming from that background, more than double than even other London prisons.”

A rarefied prisoner means rarefied surroundings, and for many debtors, a higher premium was placed on paying large sums to transfer to the Fleet than paying off debts. For a discerning inmate in the 1790s, there was even a pamphlet, The Debtor and Creditor’s Assistant, which mentions the excellent views of Surrey that a room on the third floor at the King’s Bench afford the occupant.

Rackets, its rules shaped by the high wall and the wide prison yard, became a vital part of the day-to-day social programme, like drinking in the prison’s coffee shop or ale house.

Dr Wakelam asserts that a spell in debtor’s prison wasn’t the social black mark one would assume, but common across British society.

“It was almost like a badge of honour. It’s a good example of how a game like rackets that is popularised in this one very specific area, can spread out because there are so many people in London coming into contact with it.”

Debtors who had grown addicted to the game at the Fleet exported it next to public schools, like Harrow. Before a covered court was built at the school in 1865, the boys played in the walled school yard in an imitation of their profligate fathers.

Rackets is characterised by its fast-moving ball which connects with all four walls making a specific clicking sound. Credit: Tamara Prenn

Rackets is characterised by its fast-moving ball which connects with all four walls making a specific clicking sound. Credit: Tamara Prenn

Public schools have remained the cradle of the sports. Of the seventeen courts in the UK, all but three are in independent schools, and only one of those, St Paul’s School, is a day school. The opportunities to come to the game as an adult are rare – although Stout once taught a 70 year old man who had wandered into the New York pro shop and declared an interested in wanting to learn – as a pupil, however, you could find yourself accepted into the community almost by osmosis.

Steve Tulley has been the professional and Technical Director of Rackets at St Paul’s School since the school’s first court was built in 2001. The court was partially inaugurated by St Paul’s first world champion, Neil Smith, who chose it as one of the venues to defend his title.

At the start of every year, Tulley faces the obstacle of attracting new players to a sport almost none of the thirteen-year-olds have heard of. His way of overcoming it is hands on.

“I tell them I’m expecting them to miss it.” Tulley says, explaining how he invites all of the new boys to gather on the court, and simply hit a fed ball.

“It sort of takes the pressure off. You’ve never seen a racket like this. Before, you play tennis – the racket’s bigger, balls bounce evenly. You’re going to get a shock.”

If the ball is hit at all, it ends up in the roof, or the gallery, or glancing off a classmate.

“It gives me a chance to pick out 20 guys that look like they’re coordinated enough. But how do I keep them going?”

As well as relying on the school’s other sports coaches to tip him off by identifying talented all-rounders, the trick is letting the slim area between Tulley’s office and the court, lined with lockers and three or four threadbare armchairs, become a sort of clubhouse. Here, students can while away time between practice watching the other players through the court’s glass door.

“They are in awe. You can see the whites of their eyes because they’re so, so, taken. And it’s one of those games: the gallery is spectacular, but if you can see if from there, you really get a feel that this is something special.”

At court level, the game becomes gladiatorial. At speed, the ball pursues the player, and the court’s walls appear higher. The tin, the lower line on the front wall, that if the ball strikes making a surprisingly loud, rolling sound, or goes beneath is out, looks slender from the gallery but actually comes up to mid-thigh height.

One student of Tulley’s this year is the perfect example of the immediate hold the sport has on newcomers.

“But I’ve never seen a boy quite like this.” Tulley says.

“He’s not one of the most talented. But he’s going to make it, because he’s going to be here every second.”

Tulley runs sessions on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays for the strongest players, and the student wasn’t invited. But he turned up.

“I crumble.” Tulley admits.

“We would rather have that mentality than somebody who technically and physically has everything. When you've a boy that’s got a heart the size of a lion.”

Queen’s Club, London – Saturday 6 November

The crowd is small but committed. The gallery, high above the court, is packed, and spectators talk over one another, clutch drinks and jostle elbow-to-elbow to look over the parapet down at the four players barely distinct in whites walking onto the court.

“If you looked forward 100 years, when no one has a grandfather that remembers the Empire, Britain’s legacy will be sports,” says Howard Angus, World Champion 1973 to 1975, as the players warmed up. This could be true, in a perfect world. There would be no greater testament to that idea than a sold-out Championship in a sport founded in an 18th century gaol.

In rackets, the serve is the first pair’s to lose: only the server can win points, and after the first server in a pair loses their’s, it passes to the second hand, giving the pair another chance for points. In the opening game, Larken and Stout won the first six points quickly, before Billings could even take his first serve.

The challengers won two points before the titleholders took the serve back, as if that was all Billings and Owen were allowed. Larken and Stout won three more. Then came the lets.

There are no scarcity of lets in a rackets match, particularly in doubles. With the ball moving quickly, ping-ponging across corners, off walls, attention must be paid to where your opponents are, where your partner is, where you stand, and who might be likely to collide with you. A player can innocently impede their opponent’s route to the shot in the melee, and that opponent can appeal for a let.

Reseting for a let creates rising pressure. Every time Billings and Owens sought to win back the serve, there was an obstacle.

When they finally won it, they didn’t want to let it go, and won the first game 15-9.

Billings and Owens are the more vocal pair, constantly calling, responding, patting each other on the back. They’ve played together since 2015, and they’re close. The nature of the sport demands it.

“I used to find it a little harder,” Billings says.

“I’m responsible here. I could let him down. This could be awful. But now I find it really enjoyable. Because there’s someone else to go through it with.”

They win the second game, 15-6, and the third, 15-10. The mood is changing, the rallies are longer, and the points fought more aggressively. Angus remarks of one of Stout’s shots that he’s never seen a ball hit harder, which for someone who has been present in the game for the better part of fifty years, is quite the claim.

Throughout the match, the marker will call the ball into play so the competitors know the ball is good.

Going three games down in a World Championships is not something Stout has ever experienced. The fourth game is his opportunity to put everything behind him, to claw back two games for the pair to start the home leg with momentum behind them.

Billings and Owen lead, just, 12 points to 8, when Stout and Larken takeover serving, and Larken has a strong second hand to take the titleholders to 14-12. Then there’s a let.

The lets in the fourth game have a different quality, as winning them hands that pair a mental advantage. But as Billings and Owen go level to make it 14-14, then go on to match point, Stout plays a higher card, and asks for a new ball.

A rackets ball is a polyurethane core covered in string, or tape, before a first or second layer of tape is wrapped over it, then a third layer of white tape, to make the world’s most lethal ping-pong ball. Hot balls are faster and bouncier, and it’s not unnatural to request one or two new balls per game to take the sting out. Or disrupt the rhythm of the server.

The crowd understands the trick, as does the marker. Owen understands it most of all, and has a full and frank exchange of views with Stout that prompts Billings to slide his racket between them.

I had asked Larken what being World Champion means to him.

“It doesn’t mean anything to me. I have so much going on in my life,” Larken downplays his defence of the title, with modesty.

As true as that is, things feel differently at match point.

A new ball is given.

But moments later, Billings and Owen prepare to go to New York 4-0 up.

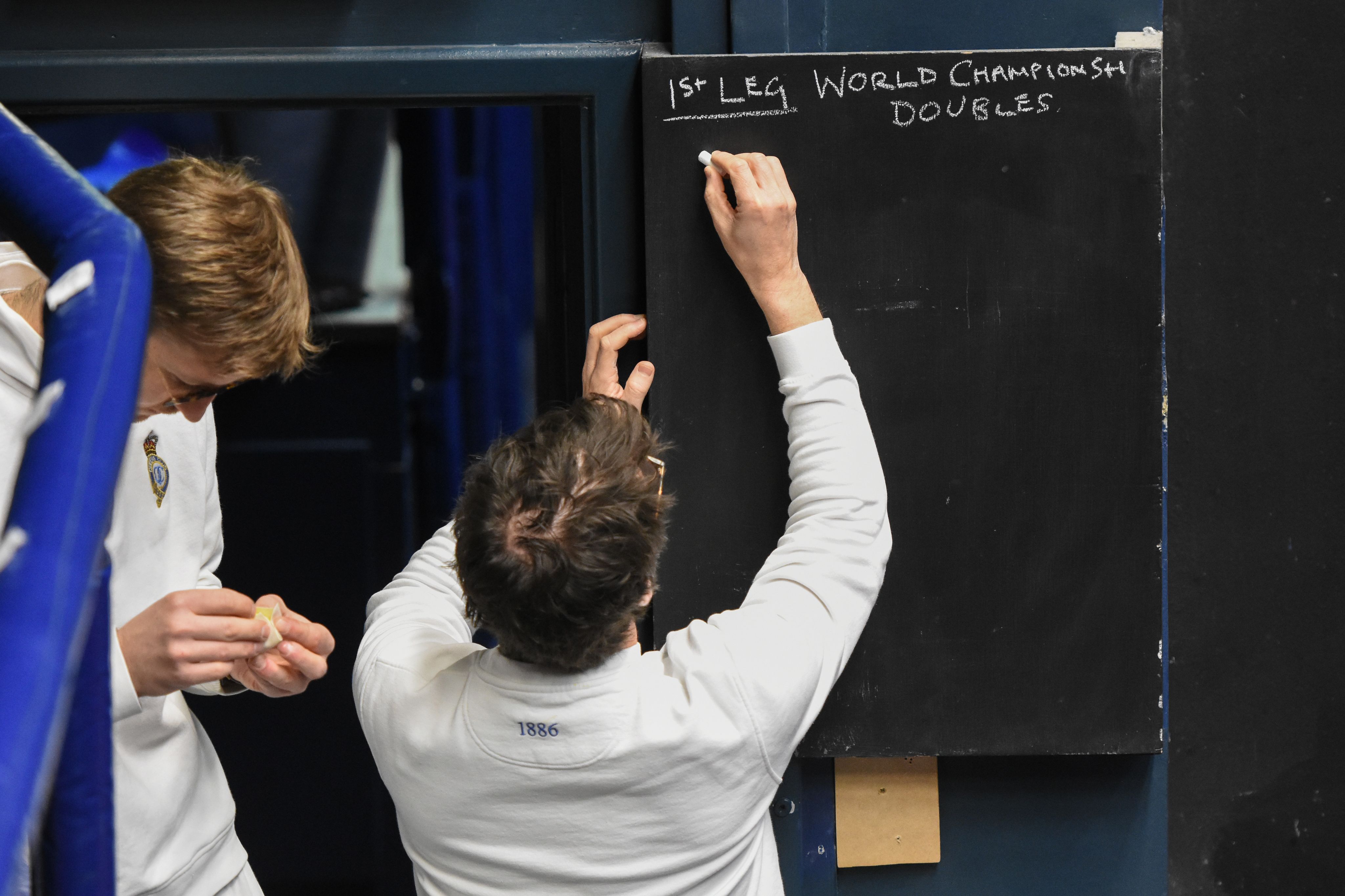

The marker prepares to keep the score on the gallery's blackboard. Credit: Tim Edwards

The marker prepares to keep the score on the gallery's blackboard. Credit: Tim Edwards

Jonathon Larker is the second hand server as the World Champions open the points. Credit: Tim Edwards

Jonathon Larker is the second hand server as the World Champions open the points. Credit: Tim Edwards

James Stout takes his serve. Credit: Tim Edwards

James Stout takes his serve. Credit: Tim Edwards

Tom Billings and Richard Owen convene after winning a point. Credit: Tim Edwards

Tom Billings and Richard Owen convene after winning a point. Credit: Tim Edwards

Richard Owen eyes a shot. Credit: Tim Edwards

Richard Owen eyes a shot. Credit: Tim Edwards

The players shake hands, and prepare for New York. Credit: Tim Edwards

The players shake hands, and prepare for New York. Credit: Tim Edwards

Tulley has taught boys like his student before, who have ended up in the second or third pair. They lost a lot. But that didn’t matter. They thought they were going to win, always, and sometimes they did.

Billings’ success represents the marriage of those two qualities, but for him too, mentality is the more important aspect of his game.

“I’m acutely aware that it’s ‘only rackets’. But on the flip side, it means so much to me.

“It’s quite insular. At times, it’s hard to find purpose, because it’s not like you’re getting paid. How are you finding the justification for this time, and the sacrifice, and the cost.

“In rackets, you have to drive yourself.”

Full or empty, the court can be an imposing, solitary place. Credit: Tamara Prenn

Full or empty, the court can be an imposing, solitary place. Credit: Tamara Prenn

Six competitions made up the National Schools Championships in December 2021, four competitions for boys, and two for girls. Over 275 students took part in the week of competitions, but participation for large open or amateur events can hope to pull a tenth of the entrants.

Tulley is realistic: “When they go off to university, hooking them back can be tricky.”

Billings adds: “How do you expect someone to spend £100 on a rackets racket, and all the costs that come with it when they leave school, just to lose in the first round of a tournament, to try and keep going?”

There are many reasons who someone might fall out of rackets and forget the power of that community. There are also people creating one or two that might compel someone to stay.

Both Stout and Billings agree that doubles aside, rackets can be a lonely sport. Solitude on the court can bleed into isolation from friends who will never quite understand the singular drive to compete at top level in a little-known sport.

That’s where, twenty years ago, the Mjolnirs came in.

The Mjolnirs were a group of younger players and followers, just out of university in 2001, who set up an open invitation to come and play, at any level, on a weekday evening, followed by happy hour. Despite starting out with a simple round-robin email, the group swelled, and is now synonymous with the informal social side of the sport.

The name, pulled from Norse mythology, is a nod to the day the group took over the courts and the bar: Thursday.

Although Guy Tassell, one of the founding members, didn’t come up with the name, he was fully in favour.

“They tried to call it the Tassellonians at one point. I said, if I die you can call it that, but certainly not when I’m alive.”

They were well-supported in their efforts, by members bringing friends into the fold, a courteous bartender who would allow for a liberal definition of happy hour.

Organisation was central to the group’s success, as more and more members travelled to international tournaments to support British players and the game itself.

Typically, Tassell says, the North American players were more sociable, which would lead to more players competing in tournaments across the country, and in the UK. Soon after establishing themselves, the Mjolnirs would make sure every tournament had five or six players involved.

The set-up is very informal, and members only have to pay a low annual sub to contribute to the Queen's Club court fees. Rather than exclusivity, the emphasis of the group is inspiring as many players as possible to stay in the game and keep the community alive.

“A really, really important part of the Mjolnirs is supporting events. Before the Stag dinner, a WhatsApp went out to say, ‘I hope we’re all supporting this, we need more names, etc.’

“That’s a strong part of it. To make sure that the rackets community is supported at all times.

“It’s not just for us to have fun and drink beer,” Tassell adds.

A crowd at a rackets match is imperative. Tassell points out the hollow sound of ball’s echo on an empty court. But with a packed gallery, cheers, rowdiness, a happy din, the players play better.

One venerable member of the rackets community told me of one match he watched, involving a Mjolnir, which sounded like a Millwall football match

This social aspect is part of the game’s core, and the traditions involved in World Championship matches reflect that. At both legs, usually on the Friday night, there’s a black tie all-male Stag dinner to toast the players, on the Saturday, often a bigger party for spectators, family, and friends.

Positions on the festivities between the players are varied. For some, it’s an opportunity to see their families. There is a recognition of the importance of ticket sales, of giving their supporters an event, and drawing more people in to follow the sport. But it’s undoubtedly complicated for either a winner, or a loser.

Speaking ahead of the first leg, Stout was adamant.

“Even if we win, I don’t want to go on Saturday night. Because we’re in the middle of the World Championship. It’s not the time to be doing out and partying, enjoying yourself,” he said.

“I should be able to do what I want, what’s best for me to perform. Playing a match on Saturday and then going to a dinner on the Saturday night, and then having to fly out Sunday – I should probably be more concerned about what’s best for my body, than having a black tie event.”

But Stout relents: “I know what rackets is. It’s definitely not lawn tennis, it’s not even squash. It’s a much smaller game, there’s less money involved.

“This is a social game – it has to be to survive.”

“It’ll be interesting, because should I ever get there, it’ll be nice to see how I respond. Right?”

The New York Racquet and Tennis Club, New York – Saturday 13 November

Unlike the Hellenic tones of Queen's Club, the court in New York is all black, dark as a tomb. It’s very fast, one of the bounciest courts on the circuit.

Stout acknowledges the different tactics needed playing London versus New York, and the home advantage he and Larken have on Park Avenue.

Another quirk: in North America, competitors have no second serve.

“I think it’s a great rule.” Billings says brightly, expanding on how the change in format is one of the many quirks that makes a World Championship special.

“The way that Richard and I played at Queen’s was to use our serves as a real weapon, and be quite close to the line.”

Billings’ serve in London is an anvil-like double-handed backhand which lifts his twisted body off the floor. A weapon is an apt description.

In New York, you take that line at your peril.

Owen and Billings both had friends and family that travelled to watch them, but even familiar faces in the high, steep, gallery can fail to warm the noisy and imposing space.

Stout opened the serving to thunder and lightning. Immediately the serves are more conservative, the game more tightly wound. Like Owen’s racket strings, broken after the game’s first 12 points.

On his home court, Stout is more assertive with Larken, directing him specifically, and they win the game 15-6.

In the second game, Larken is a steady, confident second hand server, keeping their pair just ahead until his momentum is disturbed by a shot which has him reaching with inches his length doesn’t have, and he falls before making a connection with the ball, racket skidding away from him.

Owen provides his pair with a poise and precision that Billings cannot match, so focused are his shots on decimating their opponents, and as their points go level with Stout and Larken, belief that they could win, unseat the champions, begins to stir.

They pull away. 11-9, 12-9, 13-9, 14-9.

Winning the World Championship in only two games stateside doesn’t give the crowd much for their tickets-worth. One of the peculiarities of the World Championship, wherein the importance of its social aspect becomes clearest, is to provide spectators with a match. Winners and losers, instead of retreating for a round of sweaty congratulations or commiserations, stay on court and see out the match.

They can have a brief break, but Stout, dethroned, stays on court alone, waiting for the players to return.

The remaining two games aren’t good. They might even seem like an exercise in cruelty. But they’re part of a greater tradition, so they’re played out, to applause. Billings and Owen win them.

All of the amateur players involved in the World Championship downplayed World Champion status. For Stout, naturally, it is an important part of his career.

All the players I spoke to shared details about the intensity of training, the expense, the meetings with sports psychologists and guidance from mentors within the game. If a passion for the sport is well-served by competition in general, the motivations for fighting for a World Championship are slender.

But there is never any suggestion of giving up, from any competitor. The love of the sport, its competitions and their peculiarities, and the world itself has too much of a hold on those who come into contact with it.

This is the only explanation for Billings’ participation in the Amateur Singles, less than 48 hours after winning in New York, and becoming the holder of both World Championships.

He won the competition without losing a game.

New York Racquet and Tennis Club photo credit: Beyond My Ken/Wikicommons