Hidden in Plain Sight

How rugby union is handling the endemic threat of head injuries and concussions.

Concussion is a common injury for English rugby union players of all abilities.

For decades it wasn't taken seriously, but slowly the tides are beginning to change.

For too long it's been hidden in plain sight.

What is Concussion?

A concussion is a form of traumatic brain injury that comes about when a powerful blow to the head, or another part of the body, makes the brain rotate rapidly.

These impacts damage the brain’s nodes, which are responsible for exchanging electrical signals, and dramatically alter the way in which the organ functions.

Angled contacts with the side of the head (the weaker part of the skull) are called rotational forces and can cause serious neurological harm, twisting and tearing brain cells.

Head injuries of this nature arise in all contact sports, but rugby union players experience it more than most.

When a tackler makes contact with a ball-carrier's head, or hits someone hard enough to provoke whiplash, concussion is unfortunately the likely outcome.

As the above graph demonstrates, concussions happen more frequently in the Men’s Premiership, when compared with the Women’s Premier 15s, University level BUCS Super Rugby and the amateur game.

The data, which comes from the end of season Rugby Injury Surveillance Project reports commissioned by the RFU, shows the number of concussions sustained per 1000 hours of competitive English club rugby.

The most important thing to take away from this information is that, apart from the 2015-16 season in the amateur game, concussion was the most common matchday injury across the board.

In the 2019-20 Premiership season, 22% of all injuries were concussions (19.8 per 1000 hours), while in the Premier 15s season of that same year, 14% of all match injuries were concussions (5.3 per 1000 hours).

Therefore, concussion is not an issue simply afflicting the Premiership. It impacts all corners of English rugby and that is why diagnosing concussion has become more important than ever before.

How is Concussion Diagnosed?

The loss of consciousness, while still a potential symptom of concussion, is not the only physical indication that someone has suffered a brain injury.

At times a diagnosis is not so forthcoming. Sub-concussive blows to the head also cause harm, but they do not always result in physical symptoms.

Add in the fact that it can take up to 24 hours for signs of head trauma to develop and it becomes very easy to misdiagnose a patient.

Extra precaution must then be taken to ensure a player who could be asymptomatic doesn’t remain pitch side.

Why is Diagnosing Concussion so Important?

Concussion management comes after a diagnosis and has been a relatively new phenomenon in the rugby world.

It was not so long ago that head injuries were scoffed at incredulously. Players waved off the immediate dangers, remained pitch side and put themselves at risk of severely damaging brain functionality with repeated head injuries.

Indeed, many former professionals from England and Wales, now in their 30s and 40s, have developed long-term memory loss, mental health struggles and early onset dementia symptoms because of the lax approach to head injuries which existed just over a decade ago.

In response to this phase that plagued the sport, 175 former union players have filed a class action lawsuit, targeting the mismanagement of player welfare by World Rugby, the RFU and the WRU.

The Impact of Professionalisation

The beginnings of professional rugby union in 1995 had a big part to play in the rise of serious head injuries in the sport.

Athletes soon became bigger, stronger and more skillful, meaning there were fewer mistakes, less set pieces and more collisions.

In turn, the tackle area became defined by huge collisions on a much more frequent basis, dramatically increasing the chances that a head injury would crop up on a weekly basis.

The graph below uses Opta statistics to illustrate just how prevalent the tackle has become in professional rugby since 1995.

Between 1995 and 2019, the number of tackles a team averages per game in the World Cup has more than doubled.

This phenomenon has happened across the sport.

Law Changes

In 2016, World Rugby introduced new laws to control the tackle area and minimise head collisions, making it illegal to hit someone above the chest.

Alongside this, the time allowed for full contact in training has been reduced to 15 minutes a week.

In professional matches, a Head Injury Assessment (HIA) Protocol has been put in place to prevent concussed players returning to the field.

The three-stage process includes a game day off-field assessment, a post-game assessment on that same day and a post-injury assessment 36-48 hours after the event took place.

A concussion substitute is allowed on the field while a player gets a HIA examination by medical professionals.

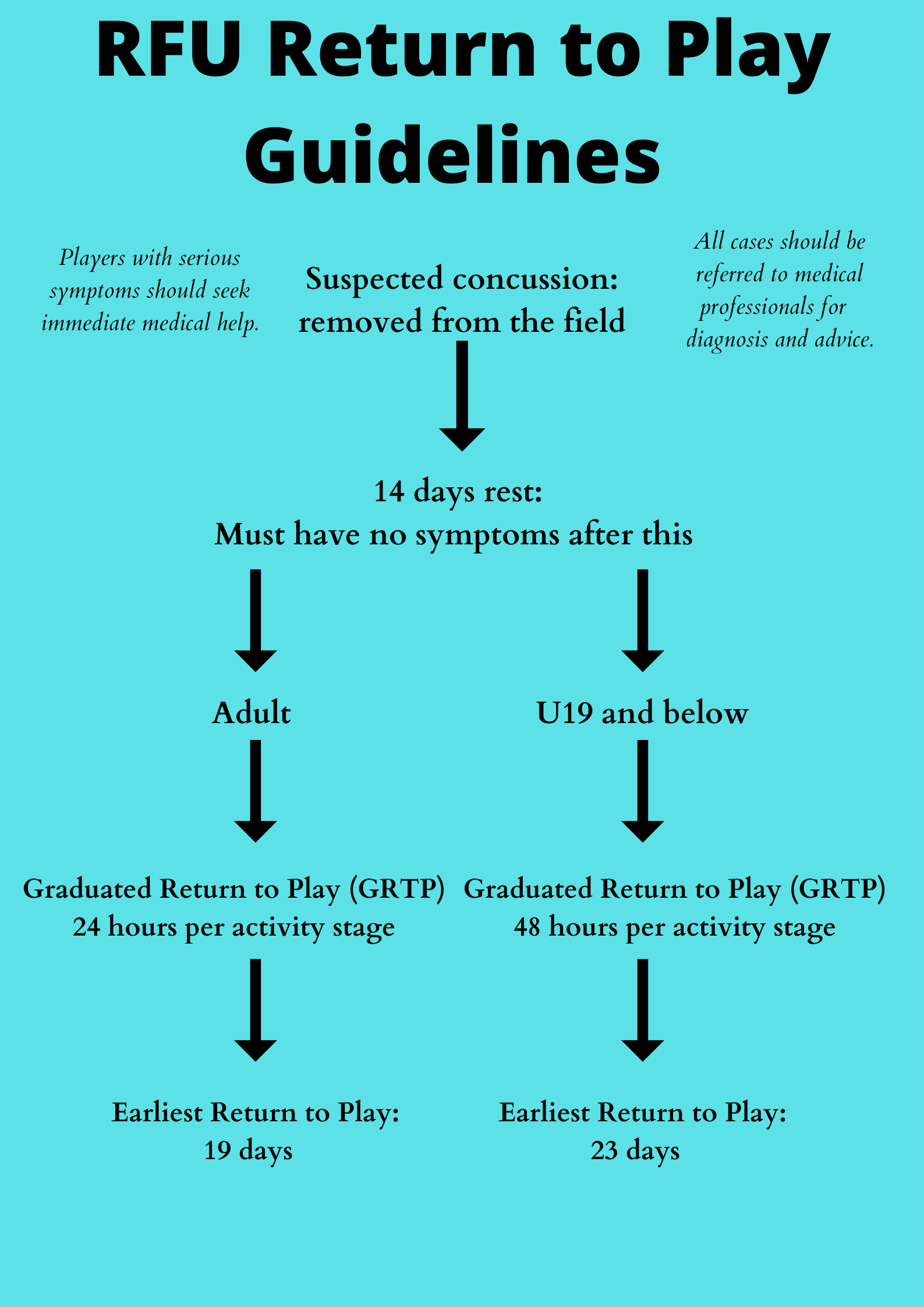

There are also more general Return to Play guidelines outlined by the RFU which apply to people of all abilities.

Despite all these changes, there is still more to be done to minimise collisions with the head.

Photo by Thomas Serer on Unsplash

Photo by Thomas Serer on Unsplash

Photo by Thomas Serer on Unsplash

Allie Schrenker

Allie Schrenker (credit: RezonWear)

Allie Schrenker (credit: RezonWear)

“I've had a few concussions myself. Every time I hit my head I cry and I think: ‘this is the end of my career’. Hitting my head and knowing what that could mean is a very overwhelming, emotional experience for me.”

Allie Schrenker started playing rugby when she was an 18-year-old freshman at the University of Tennessee.

She came from a swimming background and initially thought that women didn't play the sport but, after dipping her toe in the water, she soon became hooked.

“I was really interested in hitting someone as hard as I could and as it turns out, I'm pretty good at it,” she said.

Schrenker has gone on to feature for the USA national team and currently plays for the Durham University Women's Rugby Club, one of the best BUCS teams in the country.

She embraces the physical side of the game but has come to understand the inherent dangers carried within it.

“When you throw your body at someone else's, sometimes your head is going to get hit.

“I've had a few concussions myself. Every time I hit my head I cry and I think: ‘this is the end of my career’.

“Hitting my head and knowing what that could mean is a very overwhelming, emotional experience for me.”

Schrenker knew no better than to brush aside her head pains. But that relaxed attitude came to an abrupt end when she discovered the neurological impacts an offhand approach to head trauma could have.

She hopes that others will now be educated in the same way.

“People are becoming more aware of head injuries, but there still isn't quite enough understanding of cumulative brain trauma or rotational forces.

“People think concussion is just a hard knock on the head, when in reality your brain is flipping around in your skull.

“If the player doesn't have all that information, they're not going to pull themselves out of the game.

“We've had multiple players at Durham who’ve hit their head and gone: ‘No, I'm good’ but you can see they're a little shaken.

“I know a few girls that have had upwards of ten concussions and that terrifies me.”

To further compound this problem, newly published medical research is beginning to indicate that women suffering from concussion often take longer to recover than men.

Most worrying of all is that safeguarding procedures, introduced by governing bodies and marketed as being fool proof, are in fact fallible.

The HIA process is one such example. It is assumed that the initial off-field assessment will always correctly diagnose a head injury but how can it when sometimes it takes up to 24 hours for symptoms to develop.

To combat this, Schrenker is adamant that players should be advised to sit out if they feel any tinge of concern, especially if a physio is called onto the pitch.

Schrenker is also dubious about whether reducing contact drills in training to just 15-minutes a week will benefit the game.

“If you don't practice correct technique, you put yourself in danger.

“I’m not saying you need to go full smash every week, you just have to be mentally prepared for physicality.

“People get hurt when they're not confident in contact. If I don't know what I'm doing and if I'm scared, my body's not going to be in the correct position to accept or give contact.

“If you can't commit to it, I'd rather you not go in. So not teaching players how to do contact in the end is more dangerous because you're putting them in warfare without a clue of how to protect themselves.

Schrenker used to be a reckless tackler but now focuses intently on technique to avoid exacerbating the aftereffects of concussion which she still experiences on a daily basis.

Late last year Schrenker found a solution to her injury woes. She was made aware of Rezon, a company producing halos designed to minimise the risk of head injuries, and has since become their patron.

For the last six months she has been wearing Rezon bands while playing rugby and believes this new form of protection has benefited her, helping protect against the threat of rotational forces.

“There's a lot of technology out there, like mouthguards and scrum caps, that claim to do the things that Rezon halo bands actually do. They sound good, but they don't have the desired effect essentially.”

Rugby union continues to adapt and evolve as it trundles towards a new age. And while the sport is invariably moving in a positive direction, Schrenker, like many others, wants the shift to be much quicker.

“Who doesn't know that the brain is incredibly important to life? Everyone knows that. But we're not acting like it and it’s so frustrating.”

Battersea Ironsides Committee Statement

“We proactively mitigate the risk of serious or repeated injury.”

Battersea Ironsides are one of London’s biggest amateur rugby clubs, boasting a total of seven men’s teams and two women’s team.

The club have implemented numerous measures to ensure their players are well protected when concussed and given the appropriate time off to recover.

“At Ironsides we are very focused on ensuring coaches have the knowledge to promote safe rugby.

“Like all rugby clubs, our coaches and first aiders all receive training on the RFU concussion protocols, including using the “Headcase” online training and resources.”

Headcase is an online programme run by the RFU which teaches participants how to prevent and manage suspected concussions.

The course is compulsory for coaches and match officials that plan on participating in England Rugby training courses.

To further ensure that players do not return to the field prematurely, Ironsides log the name of each player suffering from a head injury on an online database.

“Ironsides Rugby has also invested in Returntoplay – an online injury reporting tool which provides access to specialist medical assessments and injury management – for all our players from under 5s to veterans.

“This ensures that on the rare occasions that players do experience concussion, we proactively mitigate the risk of serious or repeated injury.”

Professor John Fairclough

Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon for Progressive Rugby.

“We have a duty to produce a safe working environment that isn’t just about physicality.”

Professor John Fairclough is an honorary consultant orthopaedic surgeon for Progressive Rugby, an independent non-profit lobby group that wants to better protect rugby players of all abilities.

The organisation is made up of players, medics and academics and wants to ensure the long-term survival of the sport by safeguarding athletes from brain trauma.

Professor Fairclough has spent time working with the Welsh Rugby Union at club and international level and believes that to manage concussion, we must first understand exactly what the term means.

“Essentially, the word concussion is a lay term for brain injury,” he said. “We know that if you hit your head or it shakes violently, the brain gets damaged.”

“If you have a number of these brain injuries you get long-term problems.

“It’s been recognised, especially in rugby, that former players are developing early signs of brain damage, mental disfunction and alzheimic problems.”

Governing bodies like World Rugby, the RFU and the WRU have tried to change aspects of the game to buck this growing trend. They have enforced stricter contact laws around the tackle and ruck, making shoulder charges and hits above the chest illegal.

As a result of this, more red cards are being dished out than ever before. In the 2021 Six Nations alone, more reds were shown than in the previous ten tournaments combined and the phenomenon has left Professor Fairclough frustrated.

“The increasing number of red cards given out shows an attempt to mitigate head conditions, but the very fact more cards are being given out shows these rule changes haven’t been successful in reducing the number of collisions.

“We should be focusing on reducing the number of times the head gets injured and how to deal with the injury once it’s occurred.”

To minimise the risk of head injuries, Professor Fairclough suggests that the number of substitutions a team can make should be limited. This would encourage players to be fitter, not bigger.

“If you can bring on a fresh front row, it means those who play a full 80 minutes will come up against a fresh, heavy player. It’s like having a prize-fighter lasts eight rounds and then replacing them in the ring with a fresh boxer.

“We have a duty to produce a safe working environment that isn’t just about physicality. Before, players were looking for gaps, now they try to physically dominate someone.”

Professor Fairclough also takes issue with how the HIA Protocol functions at present. To contextualise his point, he describes how a head injury was handled when Wales faced England in the Six Nations earlier this year.

In that game Tom Francis was knocked out after clashing heads with teammate Owen Watkin and had to use the goalpost to return to his feet. The Welsh prop was called in for a HIA and subsequently passed the assessment, despite being unconscious on the field.

“If you are knocked out in the boxing ring and get up within ten seconds, it counts as a technical knockout and means you can’t box for at least 30 days,” Fairclough contends.

“Francis was knocked out and came back to play for Wales the next week.

“The HIA didn’t detect concussion which shows it cannot be used to say someone is definitely fit to return to play.”

Francis starts

— Progressive Rugby (@ProgressiveRug) March 9, 2022

Wales will see Francis coming through unscathed as vindication for their decision. Sadly, another indication of the lack of understanding around brain injury. A situation where a team’s short term gain has the potential to result in an individual’s long term pain. https://t.co/ULcdReFZUH pic.twitter.com/A0hNW6zD5Z

The fact that physiotherapists, not trained medical professionals, were the first to approach Francis concerns Professor Fairclough even more. He argues that these physios do not have the necessary medical qualifications to monitor a head injury and, because they work for a club, have a vested interest in keeping the player pitch side.

“The pressure to keep players on is very high. That’s why we need external assessments for head injuries.”

It should be noted that independent matchday doctors are now present at professional rugby union fixtures to remove this ulterior motive. That change is a step in the right direction but Professor Fairclough thinks that widespread change will not come until the attitude around the game shifts.

“It’s not a gladiatorial game. We shouldn’t be watching people sacrifice themselves.”

Luke Griggs

Deputy Chief Executive of Headway.

“We are challenging the old antiquated attitude of ‘man-up’, where people wear head injuries as a badge of honour.”

Luke Griggs is the deputy chief executive of Headway, a charitable organisation supporting people with head injuries.

The charity helps patients regain their independence and recently launched a concussion awareness campaign to widen community understanding of traumatic brain injuries.

“We are challenging the old antiquated attitude of ‘man-up’, where people wear head injuries as a badge of honour,” Griggs said.

“A lot of progress has already been made to change attitudes and awareness in sports but we have a lot further to go.

“Rugby union faces particular challenges because of its intrinsic physicality which has increased significantly since the game turned professional.

“Players are fitter, stronger and heavier now and this, combined with teams training four to five times a week, has increased the chances of potential concussion and cumulative brain trauma.”

Griggs thinks there have been signs that players, coaches and governing bodies are beginning to combat the growing probability of head injuries, but insists that there is still plenty of room for improvement.

“Rugby was one of the first sports to introduce temporary concussion substitutes,” he said.

“The rule changes happen frequently in rugby and the HIA process is always being reflected upon.

“But I don’t think the HIA system is perfect. Signs and symptoms of concussion can take hours, or even a day, to manifest, so a 15-minute assessment is not fool proof.”

Scientists are trying to develop biomarker tests which use blood and saliva sampling to quickly diagnose head trauma, but they are still in the development stage.

It will take time for these diagnosis tools to be introduced into professional rugby and even longer for them to filter down to the largely unmonitored grassroots game. That unnerves Griggs.

“We have always been focused on grass roots sport. The professional game has medics on standby but often at grass roots level they don’t have any medical professionals.

“That’s why we continue the messaging: ‘if in doubt, sit it out’, but I question whether this happens at grass roots.”

To truly generate widespread change across all levels of the game, Griggs thinks the primary focus should be on educating, spreading awareness and encouraging widespread buy-in.

“We need people to understand the genuine risk and likelihood of exacerbating injuries if you return to play concussed.

“It’s not about stopping people playing sport, it’s about protecting them and making sure they can still play four weeks later.

“The key message from Headway is we have got to guard against complacency and create an attitude of change, to make sure sport is played in a safe way that won’t risk short or long term health.”

Concussion Quiz

Picture Credits:

Human brain illustration: ra2 studio – Fotolia.com (Creative Commons)

Allie Schrenker pictures: Rezon Wear

Battersea Ironsides pitch: Noel Foster (Creative Commons)

Professor John Fairclough: Progressive Rugby

Boy with scrumcap scoring try: Stefan Frost

Luke Griggs and Headway logo: Headway

Final rugby image behind quiz: Stefan Frost