HOUSES OF HORROR: Inside Leigham Court Estate

Residents of this Lambeth estate have spoken out about the years of neglect they have faced, and the damage this has caused

Residents of an historic estate in Lambeth that has been home for generations of people are speaking out about the poor living conditions they are in, which they say is causing lasting physical and mental harm to them and their families.

South West Londoner spoke to a number of people living on the Leigham Court Estate, both on and off the record, to understand the problems that residents are facing.

Social housing tenants are living in extremely poor conditions, living with damp and mould that is affecting their health, and rising energy bills due to the substandard quality of their homes.

They say their landlord, Lambeth Council, has routinely ignored them and left them to fend for themselves.

Leaseholders on the estate are also facing problems while dealing with the council, who act as the freeholders, and are partly responsible for the properties on the estate.

Many residents say that one of the fundamental problems is the conservation order that is placed on the estate, which they say drives up the price of repairs, which in turn puts the council off fixing problems.

This report comes at a time when Lambeth has been receiving a large number of complaints.

A Freedom of Information request reveals that the number of complaints received by Lambeth Council in just 6 months has nearly matched the total number of complaints made last year.

Louisa Johnson

Louisa Johnson, a tenant in social housing on the estate, started seeing cracks, damp and mould appearing across her kitchen 15 years ago.

She called Lambeth Council to fix these problems, who sent a contractor round.

She says that the contractor told her to get on a ladder, chisel out the damaged parts of the wall and reseal it by herself.

Louisa, who says she suffers from heart problems, was shocked.

She asked her dad, a retired brick pointer, to come and fix the problem, but the cracks, damp and rot got worse and worse. Soon, more appeared across her home, including both bedrooms.

Louisa says she kept reporting these problems to Lambeth Council who, as the owner of the building and her landlord, was responsible for its upkeep.

But she was routinely ignored by them, she says, and the problems became more severe.

She became frustrated: “Obviously, they’re not bothered”, she told South West Londoner.

“What can I do?”, she asked.

Around six years ago, she started contacting solicitors in London to see what she could do about her living situation.

She and her upstairs neighbours, who were experiencing similar problems to her, contacted a solicitor in Camberwell, who said that they had a solid, winnable case.

But the solicitor said that if they lost, they would have to pay huge legal fees.

As tenants of social housing, this frightened them, and her neighbours were put off pursuing the case in court. But Louisa didn’t want to give up yet.

She founded an estate advocacy group, where she speaks to other residents of the estate to try and find solutions to the problems they face.

In November, she represented residents of the estate at a Lambeth Council meeting, where she wanted to speak about the neglect and confusion residents of the estate felt at the hands of the council.

But she was only given five minutes to speak, and the audio equipment at the meeting did not work for the first two minutes.

She also contacted Citizens Advice, a charity that, among other things, gives free advice to people in dire housing situations.

On their advice, she managed to get a surveyor from Lambeth to come to her home.

She also hired a private surveyor to give a second opinion.

Severe mould that built up in Louisa's kitchen before work was done. Louisa says that two years later, the damage is starting to come back.

Severe mould that built up in Louisa's kitchen before work was done. Louisa says that two years later, the damage is starting to come back.

Louisa told South West Londoner that this got the ball rolling, and soon her kitchen had extensive work done to it.

The work couldn’t have come sooner. Louisa said that the state of her kitchen was shocking:

“The doors were hanging off. The drawers were falling apart, and the damp was just horrendous”.

While the council initially wanted to pay for bare bones remodelling, Louisa got them to agree to letting her pay extra for a better kitchen.

She says she ended up putting £1000 into her kitchen, but added that she had to be very vocal about this to get the council to agree to it.

The damage in her home wasn’t limited to the kitchen and two bedrooms. Every room in her home had some form of damage; mould in the living room, mushrooms growing out of her bathroom ceiling and faulty electrics in her hallway.

Louisa says Lambeth initially promised to fix all the problems in her house, and had set a timescale to do this. But in the past two years, only the kitchen has been done.

Even the repairs to her kitchen have started to break down. The crack where light shone through brick has started to reappear, just two years after it was originally fixed by Lambeth Council.

She told South West Londoner that she has not been able to use one of her bedrooms in her house because of the “severe” damp and rot in it.

As a result, she has had to share her bed with her youngest son since he left the cot.

Her other two sons primarily live with their dad, who Louisa is separated from. But when they stay at Louisa’s, they have to sleep on a mattress in her living room.

The abandoned bedroom is currently used as a storage space, with boxes stacked on top of each other, touching the ceiling.

She was told last summer that work would finally be done to the second bedroom, and was given two days to clear it out.

But contractors never came.

Eventually, she had to move everything back into the room because there was no space for it in the rest of her home.

Louisa told South West Londoner that both her physical and mental health have significantly deteriorated as a result of her living conditions.

Last week, she had to cancel an arranged meeting with South West Londoner because of a heavy chest infection, the ninth she’s suffered in two years, which she believes have all been caused by the damp in her home.

She also says she is currently taking medication for depression:

“It's upsetting because these properties are so lovely; I really love this house. I'd be happy if it didn't have so many problems”.

Despite all the problems in her home, she maintains that other people on the estate have it much worse.

Shops on the estate, with rubbish piling up in front.

Shops on the estate, with rubbish piling up in front.

“If you saw some of the places other people on the estate live in, you’d be like ‘Oh my god, how can you be living like this?’”

Louisa says there is a more fundamental problem with the estate; the foundations are failing.

She believes that because of how old the houses on the estate are, most, if not all of them require structural repairs.

She believes that the required structural repairs would cost Lambeth Council £20-25,000 per property.

The high cost put them off repairing the properties, but this neglect has led to extremely poor housing conditions for residents of the estate.

“I think they’re just too expensive for the council to do major work on. But that's not my fault. That's not my problem, neither is it anyone else's on this estate. They took these on, so it's their duty to do the repairs”.

Lambeth council did not specifically respond to the allegations made by Louisa.

The history of the estate

The estate was built by the Artizans, Labourers and General Dwellings Company between 1889 to 1928 as maisonettes, flats and houses, as well as shops and a church over 66 acres.

The aim of the company was to “enable workmen and artisans to erect dwellings combining fitness and economy with the best sanitary improvements and to become themselves the owners of these dwellings in the course of a stated number of years by the payment of a small additional rent".

Streatham was only incorporated into London in 1889, and was still a village surrounded by fields which the expanding Artizans, Labourers and General Dwellings Company could buy.

Lambeth Council bought the estate in 1966. It was designated a Conservation Area in 1981, which placed restrictions on work on the buildings, and in 1996 complete planning control was placed on the estate.

Lambeth currently owns more than 800 homes on the estate, which are either rented out as subsidised social housing sold as leasehold properties.

Jackie O'Keefe

“My husband’s got cancer. He's usually asleep most of the day, because he's not well. And I have to say to him ‘You can't have the heating on all day’. We turn it on for an hour in the morning and an hour in the evening, and that’s it”, Jackie O'Keefe told South West Londoner.

As the only person in her household with an income, Jackie says she’s under an immense amount of stress, and her living conditions are doing nothing to help.

She says she reported a leak in her living room two years ago, but the council, as her landlord, has not fixed the problem to this day, despite her repeatedly reporting it.

She says that while the council will send contractors round to look at problems, they do not follow up and the problem is left to grow.

“It just seems like you're being fobbed off all the time. It just makes your life really hectic”, she told South West Londoner.

The initial leak in Jackie’s home, which she has lived in since 1997, has grown, and eventually, her TV suffered from irreparable water damage.

“[Lambeth Council] had the cheek to turn around to me and say ‘Well haven't you got insurance?”, she said.

She ended up having to buy a new TV because the water damage, which she says could have been prevented if the council had fixed the leak when she reported it.

Jackie is worried that if repairs aren't done soon, the ceiling will collapse.

She also says that she can hear water leaking in the walls.

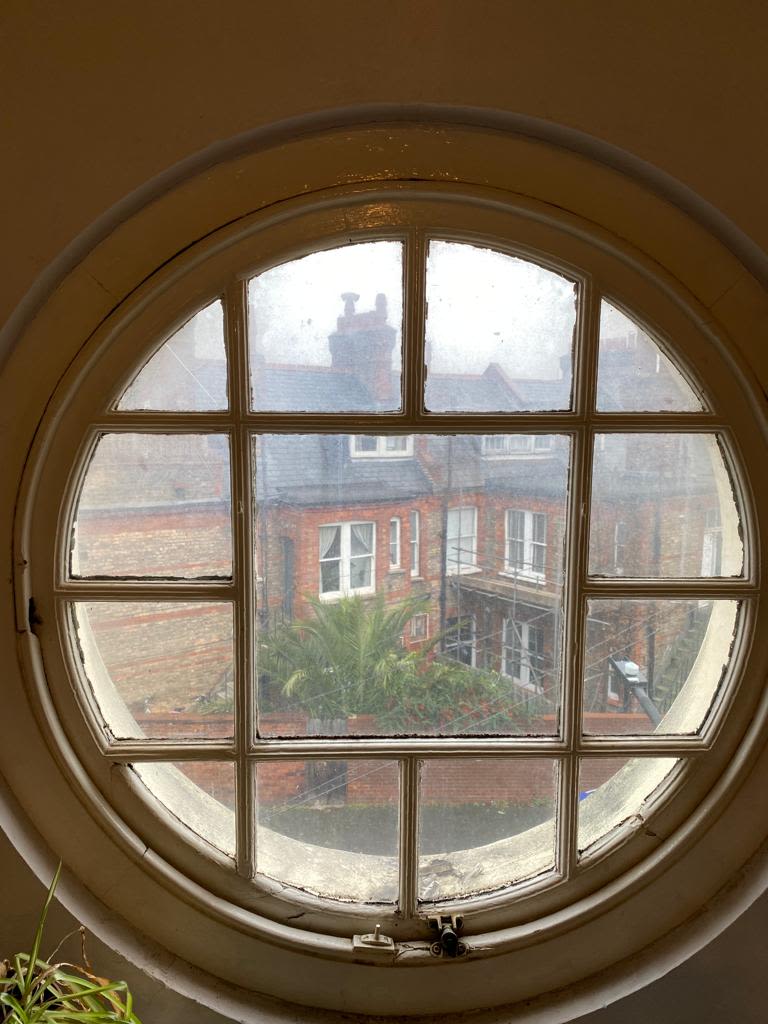

The window in her daughter’s bedroom is at a point where she cannot close it, for fear of it falling out and hurting someone on the street.

But this means her home gets bitterly cold in the winter.

Jackie says she has to put £160 in her energy meter every month, but almost always has to put more money in, especially in winter.

This means she spends twice as much on energy as the average UK household does, according to Ofgem’s 2021 figures.

With her husband unable to work, she said that money is very tight at the moment.

“I have to just give him blankets. He's not well, so he's going to feel the cold more than the next person. And he's sitting in that front room and all he can see is that damp patch with the cracks from the leak”.

She made plans to fix the window herself, but the conservation order on Leigham Court Estate has stopped her.

“They have to be wooden, especially at the front of the properties because of the conservation order of them, which says it has to be done by a company that specialises in doing round windows”.

She says that the contractor put in an order to the council for the repair in February 2020, but they didn’t hear anything back from the council.

When she called the contractor after not hearing back, they said that the order needed to be approved by the council:

“I rang the contractor after I never heard from them. They said it had been just sitting here, waiting to be approved by Lambeth.

“But when you ring Lambeth directly to follow up on these jobs, all they do is ring the contractor, and they’ll say they’ll get the contractor to ring you back”.

“It's just all excuses. You're fobbed off all the time and you get nowhere”.

Jackie, and all the residents of the estate South West Londoner spoke to, said that they had to wait for at least sixty minutes, and up to two hours, before getting through.

“If you're working, how many people have the time or even the patience to hold on for 60 minutes before you can talk to someone at a call centre who doesn't know anything about the problems, who can just say that they’ll make a note of it”

“You're going round and round in circles”.

“That put me off from ringing again. You just feel like you're wasting your time. I'm just hoping by joining [Louisa’s advocacy] group, something will come out of it”.

This was a common feeling among residents of the estate. One tenant, who wished to remain anonymous, said this:

An interview with a social housing tenant living on Leigham Court Estate, who wished to remain anonymous

“It is really stressful for me. I'm trying to work and look after the family. All while trying to deal with the council", Jackie said.

“I hate the name Lambeth, and Lambert council. I really do”.

Despite all her problems, Jackie insists that others on the estate face worse problems with their homes.

Lambeth Council did not specifically respond to the allegations made by Jackie.

The conservation order

A conservation order, which is designed to preserve the architecture of an area, was put on the estate in 1981.

The Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 says that conservation areas are those of “special architectural or historic interest the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance”.

Historic England, the public body tasked with protecting historic pieces of architecture in England, has said that the estate is in a “very bad” condition, and that it was “deteriorating significantly”.

Lambeth Council’s own conservation guide says “The estate was built to live in as well as look picturesque: with good quality building at low cost, with light and air to every room”.

#Streatham Hill looking towards Amesbury Avenue from Streatham Hill Station, c1912. Note the advertisement for homes on the Leigham Court Estate (ABCD estate). #housing #streets #postcards #shoplocal pic.twitter.com/guXmGODaDd

— Lambeth Archives (@LambethArchives) February 3, 2021

The conservation guide has 10 principles that are meant to direct the management of the estate, which are designed to “encourage and control the execution of minor alterations to ensure they do not upset these designed and created patterns”:

1. Prevent decay and repair correctly when necessary.

2. Retain maximum original fabric and reinstate missing features.

3. Replace only when necessary, with exact replicas using original materials.

4. Where possible, undo previous bad repairs or alterations.

5. Alter or extend in the same manner as the original building, avoiding extensions that undermine area character.

6. If the house is one of a group designed as a whole, consider the effect of proposed changes on the complete group.

7. Get expert advice and be a good neighbour.

8. The street front matters most, including front boundaries such as hedges and railings.

9. The smallest details, including window frames, door furniture, chimney pots, front paths and all ornamental decorative features can have considerable impact.

10. Planting and landscape schemes are part of the original design. Survival of soft landscape (trees and hedges) and hard landscape (paving, steps, walls) is crucial to area character.

Tom Gray

Tom Gray and his partner moved into their home on the estate in May, and it quickly became clear that there was a significant drainage problem at the front of their house.

It has caused a slip hazard, which Tom says runs the risk of their elderly neighbour falling and hurting herself.

As the leaseholder, Tom and his partner are responsible for the inside of the house, but Lambeth Council, as the freeholder, are legally responsible for maintaining the outside of the property.

They registered this complaint with the council in July, who set down dates to come and fix the drainage problem.

Tom says the council missed the deadline by 10 days, instead turning up unannounced and only fixing part of the problem

He says he has had around 50 back and forth emails between various people at Lambeth Council about the problem, and it has still not been fixed.

“The long and the short of it is something is not working internally at the repairs department. The repairs aren't happening in a timely manner, the communication is poor. And perhaps the most frustrating thing is that the transparency is poor. You just have no idea where you're at or when things might be resolved”, he told South West Londoner.

Despite these problems, Tom insists that other people in the community, specifically social housing tenants, have it much worse:

“There are people out there with black mould and ventilation issues who quite rightly should have priority.

“In our case, it would just be lovely to know when we could expect something to be done”.

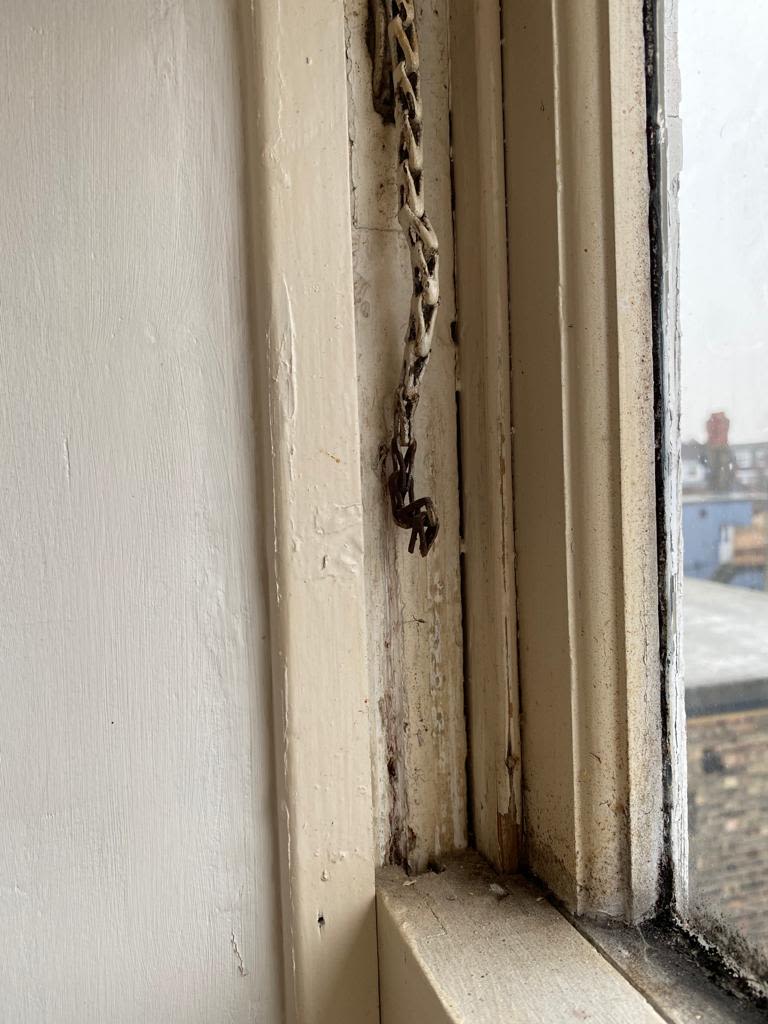

Tom and his partner have tried fixing the problem themselves, but the conservation order on the estate has prevented them from doing this.

“The house originally had bespoke gutterings. But it's completely worn through. The contractor said there was years of mud and dirt in it, and it clearly hadn't been looked at in years as part of routine maintenance, which is why it's in the state it's in now.

If they don't fix it soon, there'll be damage done to all the brickwork and the pointing”.

“The concrete piece underneath the window ledge is gonna crack and fall off at some point as well. All of this disrepair, not only is it a health and safety issue, it's going to cost the council more money in the long term”.

Tom says the damage to his home, and how the council hasn’t dealt with it, has been deeply frustrating:

“It's become a bit of a bugbear for me, particularly because we're lucky. We've got access to technology, we're relatively savvy. There are people out there without access to the internet, or mobile phones. What's it like for them?”

Nice plaque for historic Leigham Court Estate conservation area - blame Labour Lambeth 4 rubbish & decaying housing pic.twitter.com/uBNwDmcG4h

— Jeremy Clyne (@Jeremy_Clyne) May 18, 2014

One of the specific problems that leaseholders on the estate face is the process of being registered as one.

When he and his partner bought their home in May, their lawyers registered this with the council as soon as the paperwork was completed.

But Tom says it took five months for the council to update the registry.

This caused a number of headaches for the couple.

For one, they were being hounded by the estate agents on behalf of the previous owner, who was still receiving service charges.

Tom says because he and his partner weren’t on the leaseholders registry, there was a lot of difficulty accessing leaseholder repair services.

It wasn’t until he tagged the council’s head of housing services on Twitter that he received a response.

Another problem facing leaseholders was the conservation order.

“The Council isn't maintaining the conservation area. I know in other parts of the borough, leaseholders actually do things that they probably wouldn't have to do if the council did what it had to do. But leaseholders will often resort to doing that themselves, because they just can't get the council to do it.

“We can't do that in the conservation area, because we run the risk of falling afoul of planning requirements. There would be a danger of being liable for unauthorised works. You would have to pay a fine. You would also have to pay to have it sort of reverted to what it should be.

“The contractor would normally just replace the guttering with PVC that might cost £20 or £30 from B&Q. Instead they get one off bespoke that costs hundreds of pounds to put in. I don't want to be financially liable for that.

“Frankly, we shouldn't have to. That's something that the council should be proactively fixing. more efficiently.

Tom says he doesn’t understand why there are so many problems with Lambeth council’s ability to deal with arising problems at the estate.

“I almost don't care why it's not working. They just need to fix that and deliver adequate services, which is what they're paid for”, he added.

Lambeth Council did not specifically respond to the allegations made by Tom.

Lambeth Council's Response

Lambeth Council said the following, in response to this investigation:

“Lambeth has invested hundreds of millions of pounds in improving its council homes and estates in recent years, and homes on the Leigham Court Estate have benefitted from improvements including new bathrooms and kitchens under the LHS. The council is now pushing ahead with a rolling programme of improvement works, including windows, for properties on the Leigham Court Estate. This will include work to 60 homes in this financial year and more in 2022/23, simultaneously the council are undertaking external repairs, decorations and other works to 41 homes on the estate.

It is important to note that Lambeth owns more than 800 homes on the estate, which are either rented out as subsidised social housing sold as leasehold properties.

“Leigham Court, as a conservation area, is subject to a number of statutory protections designed to preserve its historic character as a pioneering example of social housing. These can present unique challenges for repairs and maintenance– for example, owners are urged to repair, rather than replace, items like windows and doors.

“The council has worked with residents on the estate over a number of years to identify the best way of maintaining their homes to the highest standard possible. We apologise for any inconvenience experienced by any tenant; we are committed to investigating problems reported to us, and resolving them as quickly as we can.”

Image Credits: Louisa Johnson, Perkin Amalaraj

Video Credits: Perkin Amalaraj