How English lessons have helped displaced Ukrainians staying in the UK

For many of the displaced Ukrainians who had to escape the conflict following Russia’s invasion in February, they spoke little English when they arrived in the UK. This naturally adds to the severe degree of anxiety they endure after leaving their homes behind amid the horrors of war.

Since their arrival in the UK, charities and volunteers have been running free English lessons for displaced Ukrainians to help them feel more at home. The impact of this has been undoubtedly positive, significantly improving their quality of life. It offers them community support and helps them get by in daily life, enabling them to read street names, navigate transport systems, apply for work and speak to others.

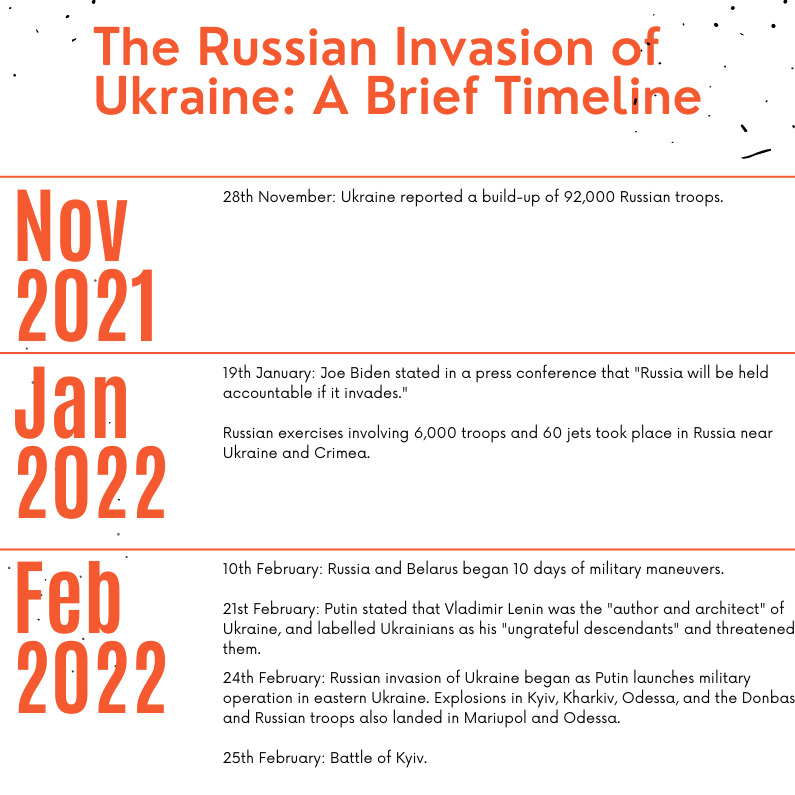

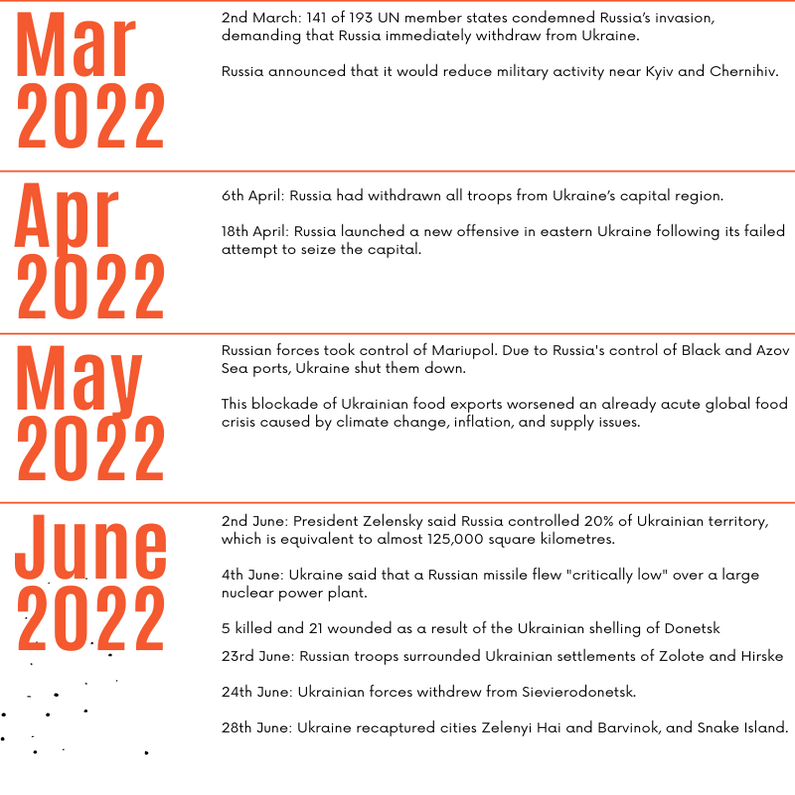

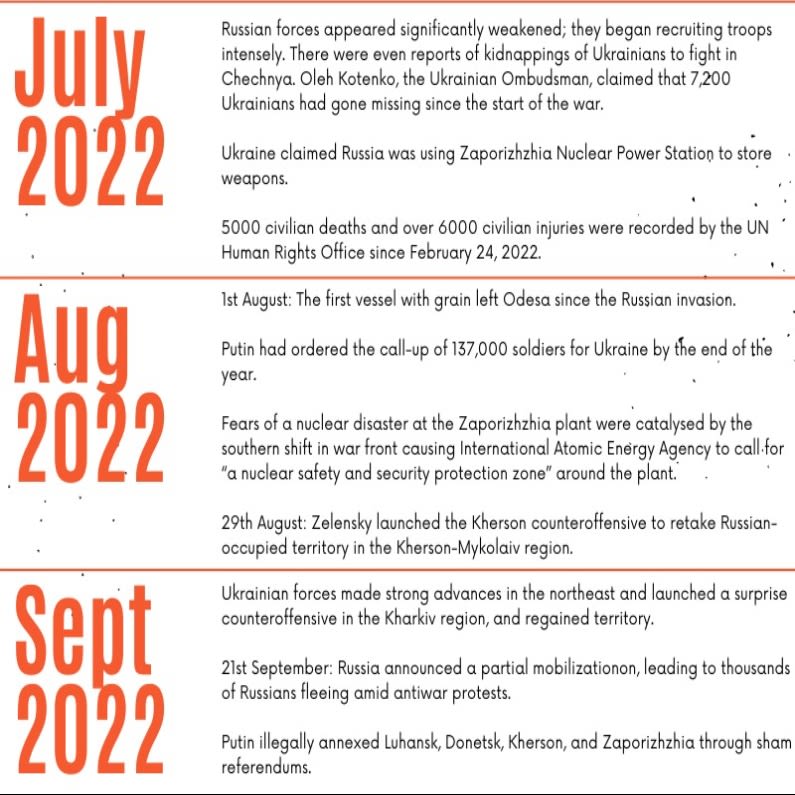

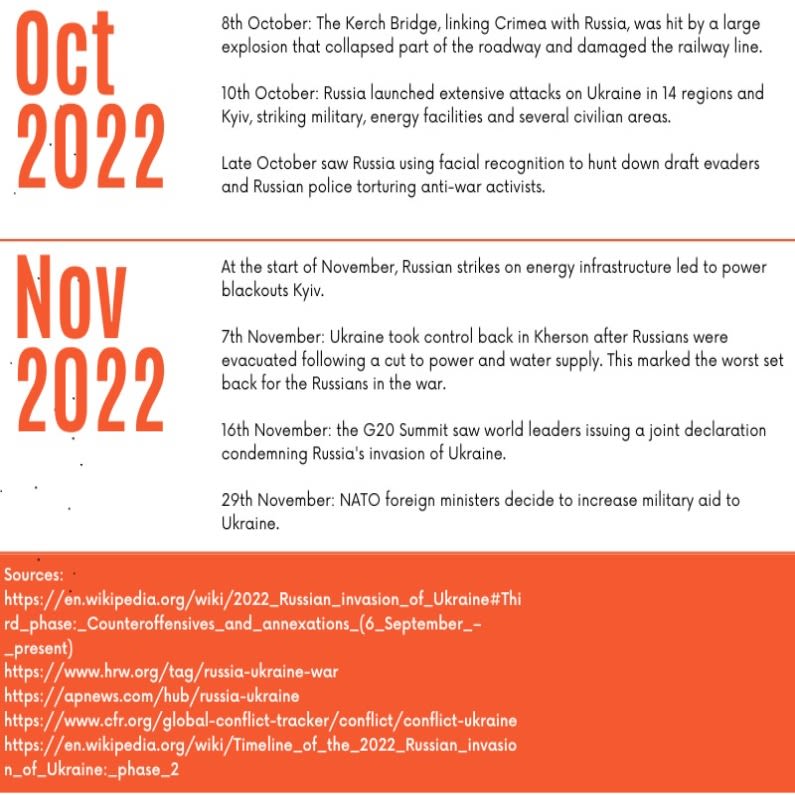

The Russian Invasion of Ukraine

On 24th February 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine, in a dramatic escalation from the Russo-Ukrainian War in 2014. The invasion led to tens of thousands of deaths on both sides, with 7.8 million Ukrainians having to flee the country by 8th November 2022. This resulted in Europe’s largest refugee crisis since World War II, as well as global food shortages.

As a result, the invasion has been met with widespread international condemnation, with protests occurring around the world. In November 2022, Nato pledged to give more weapons to Ukraine and help fix the critical energy infrastructure that was damaged in Russian missile strikes, leaving millions without electricity, heating or water. With winter temperatures hitting below freezing at the time, fears of increased deaths caused by hypothermia grew.

Anxiety around the safety of the country’s nuclear power plants were exacerbated on 21st November, when there was an unprecedented emergency shutdown of all four plants, Zaporizhzhia, Rivne, South Ukraine and Khmelnytskyi, as two generators were damaged in a Russian air strike. The International Atomic Energy Agency reported that the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant in southern Ukraine lost all access to external electricity from overnight shelling, as the power lines 50-60 kilometres from the plant were destroyed. Negotiations on a safety and security protection zone of the plants, to prevent risk of nuclear emergency, have been at a stalemate for months.

The crimes against humanity in Ukraine since 2013, including war crimes since the 2022 invasion, are being investigated by the International Criminal Court. The Russian authorities and armed forces have committed multiple war crimes including, but not restricted to deliberate attacks against civilians, massacres of civilians and torture and rape of women and children.

Many Ukrainian families therefore had little choice but to leave the country. However, a lot of fathers, brothers and husbands have had to stay behind to help the war effort, meaning families have been split apart, with no knowing of when they will be reunited.

The move to the UK

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the UK Government introduced two new visa routes to allow Ukrainians to come to the UK during March. On 4th March, the Ukrainian Family Scheme allowed them to join families in the UK for a stay of up to 3 years, and on 18th March the Ukraine Sponsorship Scheme (Homes for Ukraine) allowed them to come to the UK if they had a named sponsor who could accommodate them for a minimum of 6 months.

It was then on 3rd May that the Ukraine Extension Scheme allowed for Ukrainian nationals and their immediate family members, who had come to the UK any time after March 18th, to extend their stay, allowing them to work and study. Those providing housing for displaced Ukrainains for at least six months received £350 a month, and councils received just over £10,000 per person, with additional funding for schools.

This graph shows that by the end of March, 26,920 visas were granted to Ukrainians through the government schemes. By the end of June, this had grown to 143,881, and by the end of September, the numbers reached 189,131.

As of 5th December, the number of displaced Ukrainians who arrived in the UK via the Ukraine Family Scheme was 42,100, and was 107,100 via the Ukraine Sponsorship Scheme. As of the 6th December, the total number of permissions granted for Ukrainians to extend their stay in the UK was 22,200.

What has life been like for displaced Ukrainians staying in the UK?

There are many charities and organisations helping displaced Ukrainians while they stay in the UK, including the Refugee Council.

The Refugee Council has teams in Lewisham and Lambeth, both in South London, that support Ukrainian refugees on the Homes for Ukraine scheme. Their work includes helping Ukrainians book appointments for the Ukrainian Extension Scheme, register with GPs, dentists and opticians, obtain a SIM card with data and an Oyster card and apply for a National Insurance Number.

It also helps them register for ESOL classes and other further education, and provides them with community support, mental health support and much more. In the Lambeth Homes for Ukraine team, they support 339 Ukrainians, providing them with help for 8 months, and in Lewisham they help 357 Ukrainians, assisting them for 6 months.

The Refugee Council has received support from local organisations such as Community Tech Aid, Bookmark, Baytree Centre, Lambeth College, Black Prince Trust, and White Eagle Club. In addition, the British Red Cross has provided Ukrainian refugees with SIM cards and Barnardo’s provides free helplines for mental health support.

Krista Toivonen, a senior resettlement worker based with the Lambeth Homes for Ukraine team, explained that the most positive feedback they have received from displaced Ukrainians has been that the kindness of the workers has enabled the Ukrainians to feel supported during this difficult time. She also noted that the importance of providing Ukrainians with the opportunity to apply for ESOL classes to practice or learn English is profound.

Krista said: “I think the impact is almost undoubtedly enormous as this will facilitate multiple aspects of their life such as understanding their rights in various arenas, being able to participate in social life and empower themselves.

“Improving English can help clients with combatting barriers related to finding work in the UK as with increased English skills clients are more likely to be able to, for example, learn about the labour market, their rights in the workplace and the process of becoming employed.”

The vast amount of support provided by the Refugee Council is demonstrated through Nataliia Stegniyn’s story. Nataliia came to the UK from Ukraine in April and has been working with Refugee Council support worker Taitum Caggiano, who helped her settle and find a home in the UK.

In an interview with Sonia Lambert, Nataliia explained how dreadful it was to come to a strange country, but that London welcomed her with open arms.

When describing her relationship with Taitum, she said: “I’m very happy that I met Taitum. She really, really helped me a lot. I thank God that I met her. I was worried a lot, before our meeting, but when I saw Taitum, I saw her smile, all the fears disappeared.

“It’s very dreadful to come to a strange country, especially when there’s war in my own country. The first thing is I was looking for safety for my son and me, and we were scared because it’s a different country, different people, a different mentality. Taitum offered psychological help which really helped to release the stress.

“My son found it difficult to move to a completely different country. He also misses his father a lot. Luckily we found him a school, we found him activity classes like Karate, and now he is happy, because that can distract from those thoughts."

Taitum explained that Nataliia was the first client she met on the scheme in her role, and reciprocates Nataliia’s gratitude to her, stating that she couldn’t have gotten luckier as Nataliia has such a bright and warm personality.

Taitum provided insight into what it is like for Ukrainians to arrive in the UK, and what support the Refugee Council gives, detailing that they work to help Ukrainian clients in a way that suits their personal situation. They hold initial assessments with each client to learn more about what would be most beneficial for each individual.

However, concern is being raised about the problem of homelessness for Ukrainians as the Homes for Ukraine Scheme is starting to reach the end of its 6-month sponsorship for many Ukrainians, and this, Taitum described, has been the biggest challenge recently.

Taitum said: “There’s a lot of support available, but the first of the six-month sponsorships have started reaching their ends. Today one of the things Nataliia and I will talk about is private renting options for when her sponsorship comes to an end in the coming months.

“Unfortunately, housing issues have been one of the bigger challenges of this role. Not only have there been hosting agreements coming to an end, but there are also sponsorships that have been terminated early for a variety of reasons. It can be really challenging.”

Antonina Valianikova, a displaced Ukrainian living with a family in East Exeter, arrived in England on 16th May. She came with her daughters from Lugansk in East Ukraine. She now works as a care assistant in Elizabeth Finn Lodge.

She explains what it was like to come to the UK after leaving Ukraine.

I have been teaching her and her daughters English remotely on weekends for the last few months, and she described the positive impact having support in practicing the language has had.

She hopes to stay in the UK for as long as possible with her children, as, despite it being difficult at first to arrive in a new country, she now feels safe.

Yulia Kohut arrived in the UK on 16th April, after leaving Warsaw, Poland, where she went on 28th February shortly after the war broke out in Ukraine. She decided to leave Poland, as with so many displaced Ukrainians seeking refuge in Poland at the time, it was difficult finding any form of work. Yulia needed to find somewhere where she could provide for her nine-year-old daughter and where her daughter could go to school.

She had initially been continuing her work abroad for Ukraine, providing services for one of the ministries, however, after she was called to go back to Kyiv in May for work, she had to hand in her notice as it would not have been safe for her and her daughter to return. She is now staying in East Horsley, Leatherhead and is due to start work in Guildford College as a community language facilitator.

She explained what it has been like to come to the UK.

In light of the hugely difficult circumstances displaced Ukrainians are faced with, it is impossible for them to plan into the future. Yulia discussed how hard it has been to be separated from her husband during this time.

As a linguistic teacher, she outlined why learning English is so important for displaced Ukrainians.

The Impact of Language

As explained by the Refugee Council and displaced Ukrainians themselves, proficiency in English to be able to apply for work is a key aspect of why English courses have been so beneficial for Ukrainians staying in the UK.

In an ONS survey, it was found that 42% of displaced Ukrainians are employed in the UK, a significant increase from 9% in April. 63% of those employed said they had a permanent job.

However, 47% of respondents said they had experienced barriers to being able to take up work in the UK. The most common barrier was English language skills not meeting the job requirements, as 58% found this as the most significant challenge when trying to secure work.

This data therefore proves how useful English courses can be for displaced Ukrainians, and the Ukrainian Institute London has had a huge part to play in helping them find their voices on English-speaking shores.

The Ukrainian Institute London was set up in 1979 to help Ukrainians learn and practice English in order to get by in daily activities. However, following the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the move of Ukrainians to the UK, the institute started running short, practical language courses in London to help those arriving.

More than 3,000 registered for face-to-face lessons and more than 2,000 for online lessons. After the Paddington Central complex was donated to the institute to host classes, the institute's English Language school grew to accommodate for the demand. The institute now has 3 schools, the Paddington school, the West London school and the Pret Foundation, for students who work in Pret A Manger. They welcome students between 18 to 80 years old for free lessons, and have carers to look after young children while their parents attend the school.

Olha Plyushch, an English School Manager at the Ukrainian Institute London, works managing students, teachers and volunteers in the three locations of the institute, and she said it has been extremely emotional working with the Ukrainians as they are all so grateful for the help they are providing. She came to the UK at the end of April, and is also Ukrainian from Chernihiv, but was living in Kyiv for the past 20 years. She started as coordinator for the language school for displaced Ukrainians in May.

She explained why learning English was so important, based on her own experiences.

She described her own experience of coming to the UK, and detailed what challenges face displaced Ukrainians.

Without a grasp of the English language, Ukrainians struggle to secure work, and without work, the time they can stay in the UK is put at risk of ending before they are safely able to return to Ukraine.

Olha raised the concern that, as a charity, the institute’s school relies on fundraising, but it is hard to find enough resources to keep the lessons going, which has been one of the biggest challenges for her in managing the school.

However, they hope to continue running the school as long as they can, because they have seen how beneficial the lessons have been for displaced Ukrainians.

The impact of language support for displaced Ukrainians is undeniable.

In an ONS survey, 52% of displaced Ukrainians had used English language courses in the UK since arriving. Of these, 85% said they were either satisfied or very satisfied.

The ONS found that in August 51% of respondents indicated they could speak English well or very well, compared to only 34% in April. For reading and writing, in August, this was 63% and 51% respectively, whereas in April, this was 39% and 28%.

While there are significant concerns rising to the surface about the issue of homelessness for displaced Ukrainians, providing support by helping them speak and learn English is something so simple for a native speaker, but can make a huge difference.

It not only helps them look after their families financially during a time of immense unrest, anxiety and heart-break, but it helps them feel welcomed and safe.

Useful resources

If you are a trained teacher of English you can get involved with the Ukrainian Institute London here, to join in with their in-person classes.

If you are a volunteer teaching remotely, some useful resources to help you can be found here, with Oxford University Press, and here, with Flash Academy.

If you are a displaced Ukrainian looking to start an English language course you can find courses with the Ukrainian Institute London here, or with the Educational Equality Institute here.

If you are a displaced Ukrainian looking for general support while staying in the UK, useful information can be found with the British Red Cross here, and with the Refugee Council here.

Let's see what you remember!

Have a go at the quiz below:

Image Credits

Title Image Credit: Karollyne Hubert, Unsplash

Section 1 Image Credit: Max Kukurudziak, Unsplash

Section 2 Title Image Credit: Ahmed Zalabany, Unsplash

Section 2 First and Third Image Credit: Ehimetalor Akhere Unuabona, Unsplash

Section 2 Second Image Credit: Lerone Pieters, Unsplash

Section 3 Title Image and Image Credit: Ahmed Zalabany, Unsplash

Section 4 Title Image Credit: Dea Andreea, Unsplash

Section 4 Image Credit: Alice Kotlyarenko, Unsplash

Section 4.2 Images: Nataliia (left) and Taitum (right) - Copyright to Sean Pollock, Refugee Council

Section 4.3 all Images Copyright to Antonina Valianikova

Section 4.4 all Images Copyright to Yulia Kohut

Section 5 Title Image Copyright to Ukrainian Institute London

Section 5 all Images Copyright to Ukrainian Institute London

Section 6 Title Image Credit: KOBU Agency, Unsplash

Section 6 First Image Credit: Noah Eleazar, Unsplash

Section 6 Second Image Credit: Karollyne Hubert, Unsplash

Final Background Image Credit: Philbo, Unsplash