How fast is your commute?

The science behind the speed of London trains

In London, rail is a way of life.

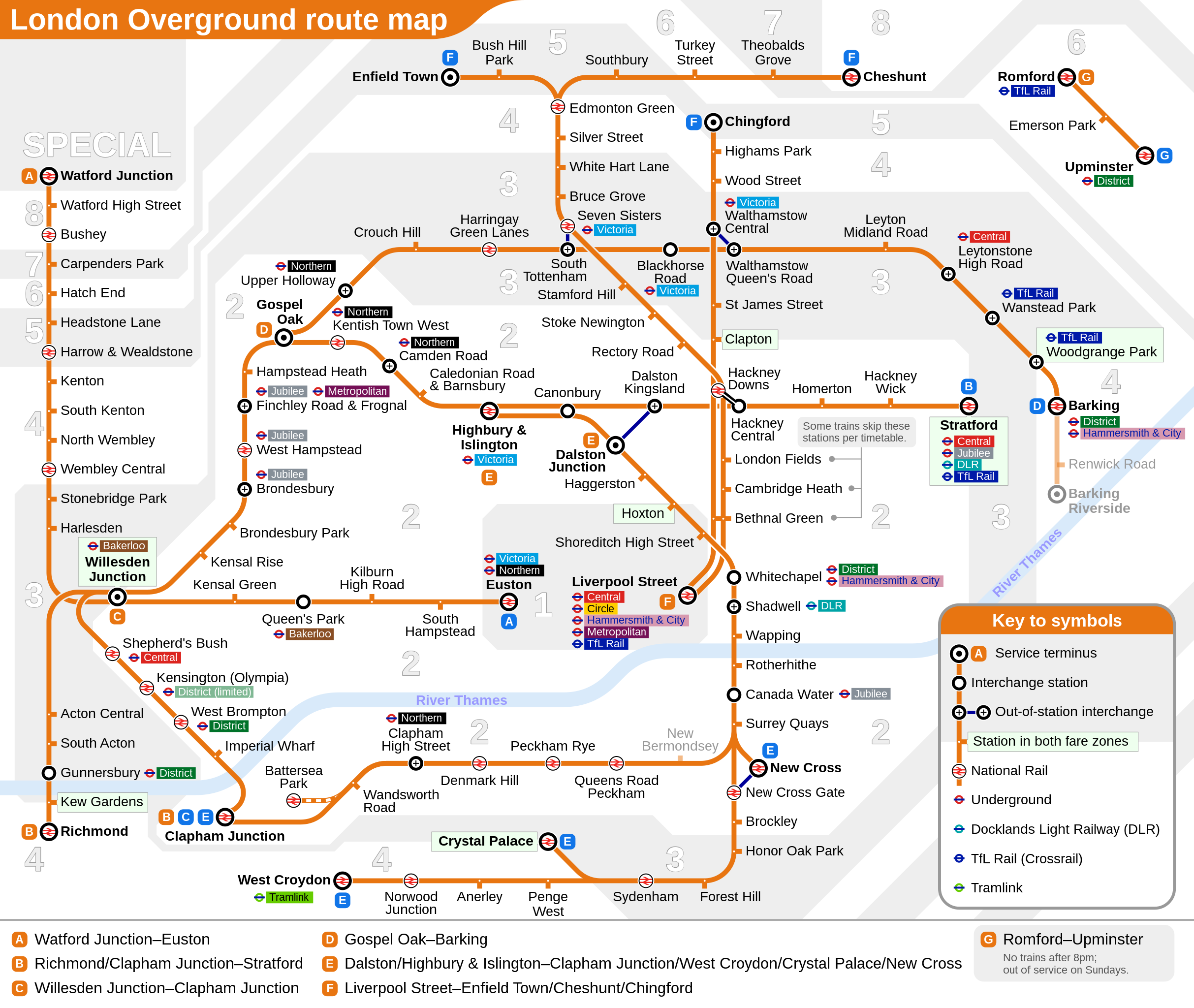

Roughly two million passengers use the London Underground every day. There are 272 Tube stations in total. Above the surface, there is a nuanced network of regional and national lines, as well as the 112 stations of the London Overground.

But, beyond the numbers, Londoners are all train-obsessives. We love nothing more than talking a novice through the fastest route to a part of the city, and secretly relish the challenge of finding alternative ways home when our normal route falls foul of cancellations.

What we are more resistant to, though, is understanding the science behind our commute. Why do some Tubes stop at seemingly random moments? What determines the speed limit on the tracks? Are trains getting quicker?

Behind the scenes, there is an army of engineers, planners and drivers striving to ensure no passenger is on the train for longer than they need to be.

In the darkness and the shadows, there are trains swerving to avoid priceless structures, speed limits fluctuating drastically and a growing push to ensure rail can preserve the future of London itself.

Below, with the help of the experts, we will learn exactly what determines train speeds across the capital.

“A nightmare of a system”

The London Underground has one distinct feature keeping speeds in check.

It is a characteristic that Gareth Dennis, a track design engineer who has worked on projects across the UK, is very familiar with.

“There are tight curves everywhere,” he says. “It’s a nightmare of a system, nothing’s straight.”

The capital’s Tube routes were generally constructed to mirror the paths of the roads above them, therefore avoiding existing buildings.

The result? Where there is a sudden bend in the road, the train line below veers just as sharply.

And whether you are driving a train, truck or tricycle, it is not possible to maintain straight-line speed during a drastic turn.

Dennis adds: “If you have got railway lines that are following either below or above [roads], the curvature has to be very tight because roads have very tight bends, particularly in grid pattern where you are doing a 90-degree turn.”

There are instances across the city where a direct train route would be ideal, but centuries of history force a more tortuous journey.

The Central line changes path almost at a right-angle near Bank for an apt reason – to avoid the vaults of the Bank of England.

PROTECT THE MONEY: A Central line train leaves Bank's curved platforms

PROTECT THE MONEY: A Central line train leaves Bank's curved platforms

Elsewhere, the Bakerloo line takes a major swerve in the city centre so that it mirrors Regent Street.

Of course, there are straight sections. The northern end of the Jubilee line and Tubes coming out of Marylebone benefit from running alongside heavy rail routes. Curves, though, dominate the capital.

Certain Tube lines, such as the Circle, District, Hammersmith and City, and Metropolitan, follow roads the most religiously.

These lines are sub-surface networks built predominantly using the ‘cut-and-cover’ technique, which involves excavating to a shallow depth and covering the top of the newly-made trench with concrete, thus creating a tunnel.

While the relatively low depth of this strategy makes it an economically appealing option, its proximity to the surface inevitably creates high disruption during construction. Excavating under roads, rather than buildings, allowed the London Underground to minimise disturbance as much as possible.

Although some houses were knocked down to make space for the sub-surface routes, particularly on the Metropolitan line, planners generally stayed loyal to the tarmac above.

Dennis explains: “Unless they were bulldozing houses, the curvature was limited by what there was on the road.

“In some cases, if you look at the sub-surface line, you’ll see that the curves are very tight because they are following that road.”

The ‘Deep Tube’ lines - the Bakerloo, Central, Jubilee, Northern, Piccadilly, Victoria and Waterloo & City - are much further below the ground and are less restrained. Some even go below the River Thames.

TWO TUBES: A sub-surface train (left) travels at a far more shallow depth than a deep Tube train (right). Credit: Wikimedia Commons/Chris McKenna

TWO TUBES: A sub-surface train (left) travels at a far more shallow depth than a deep Tube train (right). Credit: Wikimedia Commons/Chris McKenna

Innovative engineering can mitigate the hindrance curves have on speed, for example by tilting tracks inwards slightly to reduce the radius of the turn.

However, there is only so much planners and builders can do to raise the pace without reducing comfort and safety.

“We are limited by the laws of physics,” Dennis says. “In the last 40 years, we have got better at curving and better at designing trains to curve more smoothly, but that doesn’t really affect speeds.

“It’s the laws of physics and the level of comfort passengers experience that limits how fast you can go through a curve.”

“Drivers don’t control the train speed”

The similarities between train lines and roads are not limited to direction. Although there are no discreetly placed cameras or electronic signs, the Tube, like a car, is dictated by speed limits.

These restrictions are chiefly due to an attribute that the Underground’s name masks.

For an underground system, it seems strange that things go underneath it, but most of the Underground isn't underground at all,” Dennis says.

Indeed, over half of all London Underground stations are at surface level, and the District line even passes over the Thames between Kew Gardens and Gunnersbury.

Gareth Dennis explains the track characteristics that can limit speed

Gareth Dennis explains the track characteristics that can limit speed

Dennis adds: “If you’ve got weak bridges, that can influence speeds. The chances are you’ll be slowing trains to go over that structure.

“The position of signals might determine how fast or slow a train can go. Level crossings limit speed.

“Those boards on the side of a track with the speed on them are defined by all those different factors.”

Underground trains are relatively light, which mitigates the impact of varying terrain but, once the Tube reaches the heart of the capital, a more obvious restriction is imposed.

“If you’ve got stations in close proximity to each other like in central London, then you will not spend much time at top speed,” Dennis says.

“You can only go so fast when there is a station every kilometre or less.”

The average speed of each London Underground line. Source: TfL

Most of the Underground's busiest stations are also found in the centre of the city, meaning trains run slower to reduce stopping distance and therefore accommodate more vehicles on the tracks, according to Transport for London (TfL).

The situation is different on the outskirts of London, where the stations are quieter and the distance between them greater.

A TfL spokesperson added: “London Underground train speeds vary across our network, from as slow as 15mph, up to 60mph. The speed of the trains can be impacted by a range of factors including the track infrastructure, the type of signalling system, the distance between stations, and the frequency of services in the timetable. For safety reasons, our Underground trains have a maximum speed of 60mph.

“Lines like the Metropolitan and Northern lines see the greatest variation in speeds, as once they get into the suburban areas, there is more distance between stations, allowing them to get closer to 60MPH.”

And what about human error? Can drivers, perhaps too eager to stay on time, drive too fast? Equally, will inexperienced conductors ever fall short of the permitted speed?

Not anymore, says Dennis. Contemporary trains have all sorts of different systems to prevent human error.

“In the majority of cases, the drivers are just opening the doors, they don’t control the train speed.

“On the Victoria line, the trains are completely automatically controlled.

“That’s pretty much true on the Northern line now and on all the sub-surface lines.”

Besides, conductors are still required to go through around two years of training and rarely make mistakes.

Speed limits across London train lines. Source: Gareth Dennis

“It becomes second nature to them,” says Tom Cairns, an expert in software development with over a decade’s experience in the rail industry.

“You’ve got to learn your rules, your traction, the routes that you drive.

“It’s not the same as driving a car where you can just go on any road. You need to know where the signals are, where the speed restrictions are and where your level crossings are.

“The level of training is to a degree that speeding shouldn’t be a problem.”

The Overground dilemma: “A careful balancing act”

Far more complex and with dozens more stations than any Underground line, ensuring the London Overground functions smoothly is a huge logistical operation.

London Overground average line speeds. Data: TfL

The key factor, and one that does not affect the Underground, is freight. The need to balance trains carrying people and vehicles carrying goods risks slowing the Overground, especially in northern parts.

The northern section of the network, connecting Stratford to Richmond and Clapham Junction, is packed with freight. The tracks around Acton house some of the largest yards in the southeast and connect to Wembley, which is similarly busy.

“It is a careful balancing act between meeting passenger demand and freight demand because of how congested the line is,” says Cairns.

Simon Kendler is a route freight manager for Network Rail, which owns and runs the majority of rail travel in the UK. His work offers an insight that busy commuters seldom experience.

“Freight operators are a key part of the rail network and have just as much right to be on the network as passenger operators,” he says.

“We make sure that we share the network and ensure that the passenger operators are able to give the service they can to their customers whilst ensuring the freight operators can do the same.”

These trains, as long as 775 metres and carrying important goods for warehouses, supermarkets and construction, travel very differently from an Overground train.

“A passenger train will accelerate very quickly and stop very quickly. A freight train takes a lot to stop and a lot to get going again,” says Kendler.

“The key is what we do where there are delays. We would rather keep a freight train moving and get it through that area.

“We never design a timetable where trains are going to be holding each other up. However, what happens on paper is open to the whims of various things that can happen on a day-to-day basis.”

CITYWIDE: The London Overground is far more complex than any individual Underground line. Credit: Wikimedia Commons/Sameboat.

CITYWIDE: The London Overground is far more complex than any individual Underground line. Credit: Wikimedia Commons/Sameboat.

TRACK SHARING: A freight train passes through West Hampstead Overground Station.

TRACK SHARING: A freight train passes through West Hampstead Overground Station.

“We don't use rail enough”

Trains are already pivotal to life in all corners of London, but they are poised to surge in importance.

With population rising and the climate emergency worsening, maximising the railways is essential to the city’s future.

Kendler, who also works with Young Rail Professionals to promote sustainable transport, believes: “Rail is all fundamentally designed around the interface between the steel wheel and steel rail.

“The beauty of that interface is that you do not need much energy to get something moving.

“If you want to move lots of things and people very quickly and efficiently, rail is brilliant.

“We don't use that enough in this country.”

For Kendler, the UK’s reliance on cars consumes unnecessary energy and space.

“Road is not as efficient as rail. We really need to think about how we can increase our capacity for more people and things to travel by rail rather than road.

“Rail is there to take on that [sustainability] challenge and it's an absolute necessity if we want to maintain our quality of life and a habitable planet.”

Sustainable transport expert Simon Kendler explains how trains can help tackle climate change.

Such initiatives would be welcomed by train travellers, who can be assured of faster journey times if the government and public support a move towards the tracks.

The imminent opening of Crossrail (also known as the Elizabeth line), which connects Reading and Essex via central London, offers a glimpse into a rail-dominated future.

“Crossrail will be such a huge boost to London, because a journey that could have been three changes becomes just two, one or none,” says Kendler.

“A lot of the time in urban areas, where you are changing trains or transport modes, connections are where you waste time.”

It is not enough on its own. Kendler is an advocate for more ‘cross-radial’ train services that connect the west and east of London, adding that an improved journey from Wembley to Ealing is his own niche holy grail.

“London is brilliant if you want to go from the outside of London to the centre of London. If you want to get across London, though, it’s really hard,” he adds.

Other proposals, such as Crossrail 2 and the Bakerloo Line extension, could increase interconnectedness and speed. On a national scale, the High Speed 2 line should ease the pressure on London’s packed stations.

Yet, for all the irritating delays, manic connections and those pesky Bank of England vaults, Londoners have struck gold with the transport system, Dennis believes.

"What I’d say to anyone that's moaning about a two-minute delay on the Underground is for them to come up to Birchwood Station near the centre of Manchester, and they get a train every two hours if they are lucky.

"It’s an urban area. It’s got industrial, commercial, retail and a large residential area, and they get a train, at peak time, every two hours.

"London has a very, very good public transport system. People who moan about the Underground do not know how good they have it compared to the rest of the UK.”

Quiz: How is your train knowledge?

Additional picture credits:

Gunnersbury Station (second picture in 'The curves' section): Geograph/L S Wilson

London Underground map: Wikimedia Commons/Sameboat

Elizabeth line sign: Geograph/David Hawgood