How Harrow turned blue

Ethnic minorities and their voting patterns

In the wake of partygate, the pandemic, and a Conservative party accused of more sleaze than the average, the local elections were expected to be a pertinent reminder of how public opinion matters.

The Conservatives saw huge losses, whilst Labour gained the most Conservative seats and we also saw the resurgence of the Liberal Democrats and the rise of the Greens across the country.

As with any election, there were some surprising results. Ethnic minorities proved their importance yet again and showed just how volatile their voting behaviour could be.

Harrow, for example, turned blue. Though the area is predominantly Indian, the borough swung Conservative for the first time in many years.

Ethnic minority voters tend to vote on the left, as parties on the right have had a history of racism and policies that have negatively affected these groups.

In the 1990s, we saw over 80% of ethnic minorities voting Labour, and although this has lessened, it's still relatively high, especially compared to their white counterparts.

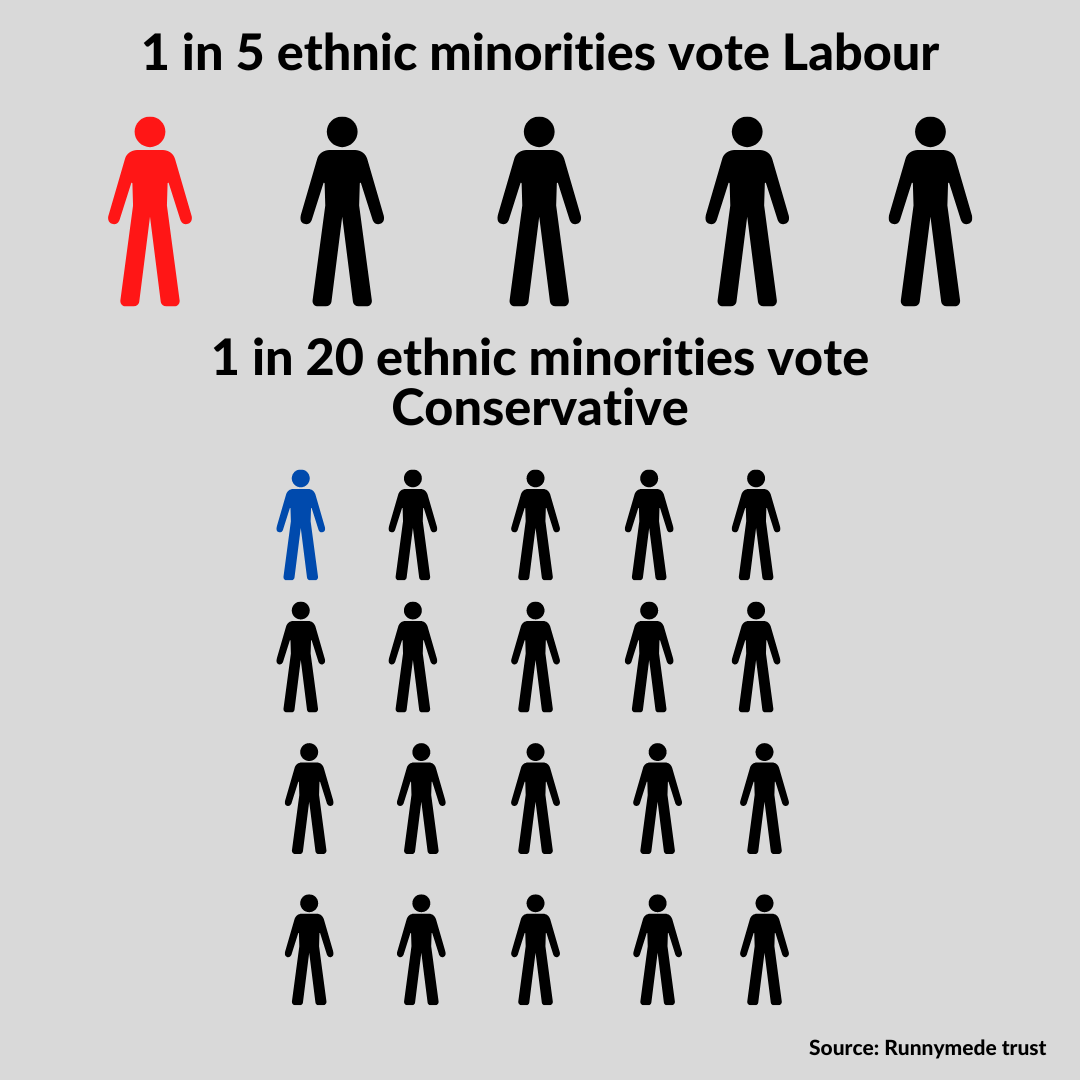

According to the Runnymede Trust, In the 2017 General Election, 1 in 5 Labour voters whereas ethnic minorities whereas 1 in 20 voted for the Conservatives.

But, why is this?

Diane Abbott speech at UN Anti-Racism Demonstration, 2019. (Sandor Szmutko/Shutterstock)

Diane Abbott speech at UN Anti-Racism Demonstration, 2019. (Sandor Szmutko/Shutterstock)

Conservative anti-immigrant leaflet. Lambeth, South London 1964.

Conservative anti-immigrant leaflet. Lambeth, South London 1964.

Dr Neema Begum, a political scientist researching ethnic minority voting behaviour, political participation and representation, describes the long history of ethnic minorities voting for Labour as down to the links between these communities and the Labour party.

The Labour Black Sections, for example, saw Diane Abbott as a founding member and the first-ever black woman MP.

The Labour party itself has long relied on the votes of Britain’s African, Caribbean and Asian communities (under the notion of ‘political blackness’ from the 70s to the 90s). It thus has made sure to be inclusive of them in their policies.

"The Conservative party, on the other hand, have had a greater history of hostility and perceived discrimination towards racialised community,” says Dr Begum.

The Windrush scandal, for example, emerged in 2017, after the Conservative Party wrongly deported and detained more than eighty people.

In 2016, Zac Goldsmith accused Sadiq Khan of ‘giving cover to extremists’ during the mayoral elections.

The current Prime Minister described Muslim women as ‘letterboxes’ and even the renowned and celebrated Winston Churchill, called Indian people ‘beastly people with a beastly religion'.

As well as policy, one thing that matters to any group is representation.

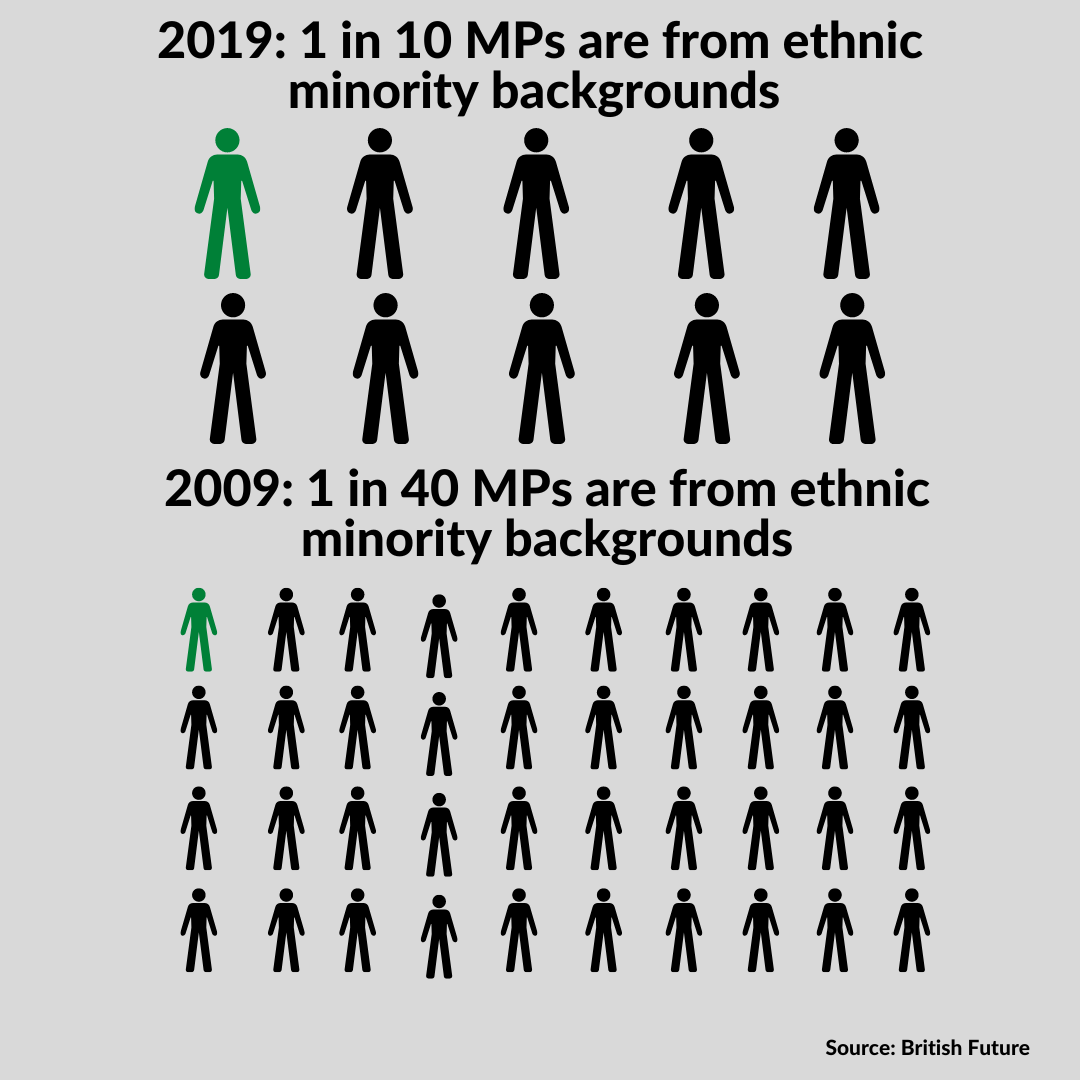

According to a research briefing by the house of commons, after the 2019 General Election, 10% of the house of commons were from ethnic minority backgrounds, that’s a total of 65 MPs.

However, as the report also states, if it was in line with the actual percentage of ethnic minorities in the UK, the number should be higher at 93.

It’s important to note, however, that this does still mean that one in ten MPs are from an ethnic minority background, whilst ten years ago it was one in forty.

41 of these MPs came from the Labour party, whilst just over half at 22 were from the Conservatives.

Just why is representation so important?

On the surface, having people that look like you is important to create a connection of understanding, especially on issues such as race and discrimination which are specific to particular demographics.

Dr Begum explains why it’s so important on the local level: “When people engage in local politics, it’s important for people to communicate with their local councillors.

"We’ve seen surrogate representation where ethnic minorities in one ward would contact an ethnic minority councillor in a different ward if their own councillor were white because ultimately, they feel more comfortable going to a minority councillor for help.”

The Conservatives have been strategic in trying to diversify their cabinet, by focusing on placing people from diverse backgrounds in safe seats in order to get them selected.

Dr Begum explains how this is a regular strategy that political parties use as well as heading directly to communities, such as Hindu Temples or Mosques, to attract candidates.

One particular demographic that continues to be interesting in its voting patterns is British Indians and this was seen during the Harrow local elections where they make up the largest demographic.

Many Indians migrated to the UK in the 1950s and 1960s.

Starting off as working class, trying to build a community in an unfamiliar country meant that Labour was the obvious choice.

Labour was a party that cared for them and kept them somewhat safe. But, the Conservatives called for tighter immigration policy and had no desire to protect these migrants.

Ethnic minorities don’t want to feel like they’re being held back by their race, which is something Labour fought against.

But as time went on, many of them began looking less like their newly immigrated counterparts but more like the wealthy, well-educated representatives within the Conservative Party, Rishi Sunak and Priti Patel.

But what is it about Indians, in particular, that means their voting patterns have changed?

Firstly, Dr Begum puts it down to “class background” and the “model minority myth”.

Indians are generally seen as being very successful in education and in business which is something that the Conservative party has tried to appeal to.

Moreover, a lot of the Indian immigrants that come to Britain now, no longer need the working-class solidarity that Labour provides.

They don't represent the factory workers of the 60s, but the upper-middle class wealthy well-educated elites like the Conservative's Sunak.

But external to the factors of their lives here in the UK, the politics of India also has sway.

Shri Narendra Modi meeting Boris Johnson, in France on August 25, 2019 (YashSD/Shutterstock)

Shri Narendra Modi meeting Boris Johnson, in France on August 25, 2019 (YashSD/Shutterstock)

British Indian Hindus who identify more with the Hindu nationalism of Modi and the Bharatiya Janata Party might identify more with the Conservatives as a result but this divides the Indian vote further.

British Indian Sikhs have a much more complicated relationship with the Conservatives.

Operation Blue Star, for example, saw the British government offering military advice to the Indian government in a crackdown on the Sikh community.

The actual events at the Golden Temple in Amritsar, Punjab lead to the death of thousands of civilians.

Sikhs, thus, do not respond as well to Hindu nationalism after seeing firsthand just how divisive it’s been.

One thing that's for certain, however, is it will take much longer to see an overall shift to the Conservative party.

Yes, it is happening across the British Indian demographic, but it isn't as large as it appears.

We also can't fully understand the volatility because as with a lot of minority groups, there isn't actually enough survey data...

Although election results are showing that some voting patterns are changing, it’s still really difficult to get a full understanding of why this is and what those explicit changes are.

Dr Begum says: “There isn’t enough data or it’s a real problem doing research in this area because so many surveys are online - it’s a lot more difficult to capture the ethnic minority population.”

It’s hard to gauge exactly how much Indian politics are affecting polling choices, why the Conservatives are becoming more appealing to the Indian communities and just how likely future results, like that of Harrow, are.

Many experts rely mainly on anecdotal evidence and even that is few and far between.

Ben Walker, co-founder of Britain Elects and senior data journalist at the New Statesman explains the problems with polling in the video below:

Overall, we have seen a shift amongst ethnic minorities to the right but the shift isn't as sharp or large as we think.

It will take years for a whole demographic to move away from the political sphere that connects them to their experience of being the other.

It will be interesting to see, as we hopefully gather more data, where the ethnic minority vote heads, especially in times of such polarisation.