'I am unstable'

Living with Complex PTSD

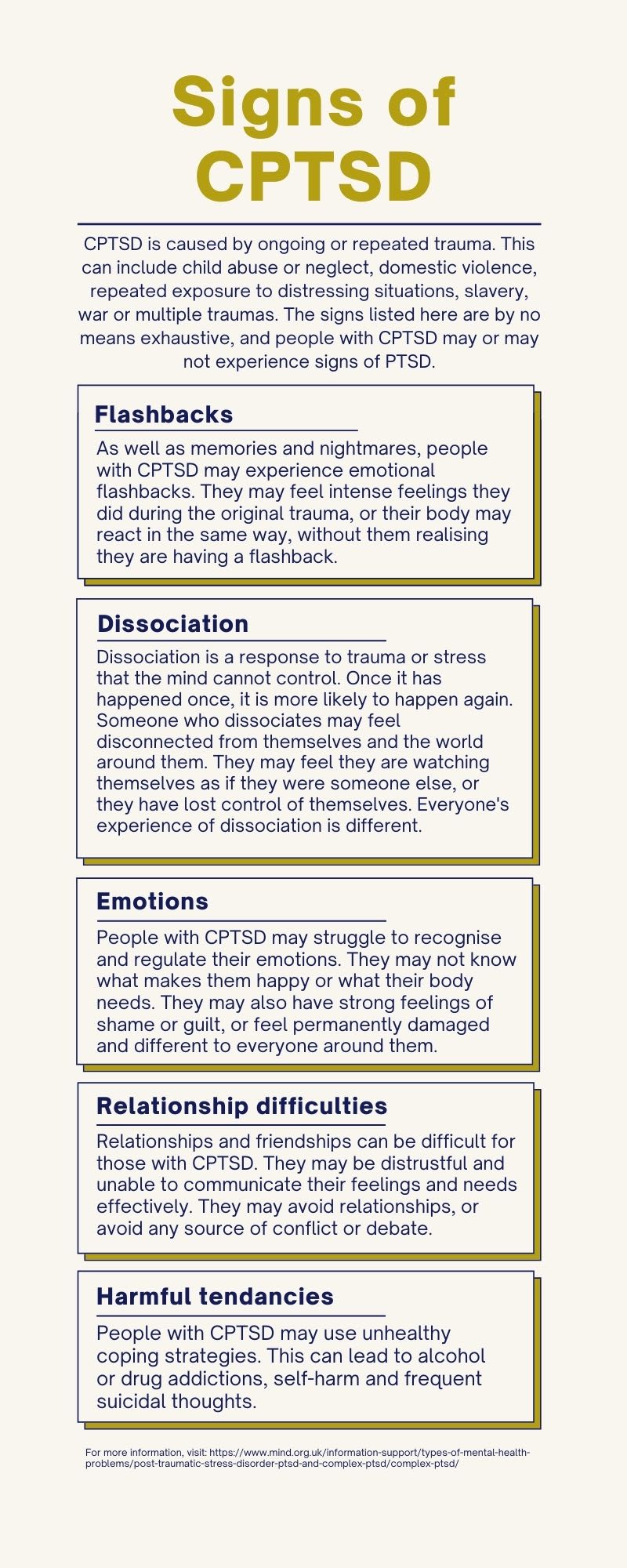

Complex PTSD, or CPTSD, is caused by repeated or ongoing trauma. It is a mental illness that can have a moderate to severe impact on someone’s life.

CPTSD is a relatively new term, and not all medical professionals are aware of it. Mental health charity Mind explains some people may be incorrectly diagnosed with BPD or other personality disorders.

“I’m scared of myself. Sometimes my behaviour isn’t me, it’s a continuing trauma response that I deal with every day.”

But if someone has symptoms and has experienced trauma, it is likely they have a form of CPTSD.

Someone may not develop it until months or even years after trauma occurs.

“It’s who I am in every aspect of myself. My life has been shaped by these traumatic experiences.”

SWL spoke to five people with CPTSD about their day-to-day experiences of the condition.

Each individual mentioned in this article has CPTSD. Each of us is doing a different type of therapy, and has completely different symptoms and experiences.

But common threads of emotional issues, various forms of flashbacks, and relationship problems connect us all.

Every person expressed frustration that there is no treatment recommended or offered by the NHS for CPTSD.

Most of us have been diagnosed by a private therapist.

In several of the interviews, it was clear the cost of private therapy is just another source of anxiety.

The NHS website states people with CPTSD may be offered treatment for PTSD, and treatment for ongoing issues such as self-harm and addiction.

No-one I spoke to for this article has successfully received any NHS treatment for PTSD.

Sophie's story

Sophie's name has been changed to protect her identity

Content note: Sophie's story contains discussion of addiction and suicidal thoughts.

Sophie discovered CPTSD online after a doctor said she could be experiencing a form of PTSD. But while they offered to treat her for anxiety, there was no offer for treatment on the NHS.

Sophie is in her second year of university, after intermitting due to her mental health last year. During her time away from university she began private therapy.

She said: “I think the complex bit of CPTSD, the bit that particularly resonates with me is the anxiety and depression that comes with it, and the dangerous behaviours.

“When I was in my very worst spaces, I had massive addiction issues and was incredibly reckless. All of these damaging behaviours that you don’t even relate to your trauma until you go into therapy.”

Sophie struggled with alcohol addiction and now does not keep alcohol in her flat.

“If I can’t sleep the urge to take the edge off with alcohol or painkillers or anything like that, just so I can rest, is so high.

“It’s not something that I do actively but it’s something I’m always frightened I’ll do.”

She still drinks, but has to be extremely cautious.

“I’m always thinking, am I drinking to take an edge off because I’m feeling a certain type of way, or am I drinking because I’m with my friends and I’m enjoying myself?

“If I cry at the end of this, is that because I haven’t let any of my emotions out for three weeks, or is it just because I’ve had too much to drink?

“You constantly question your decisions.”

Sophie described struggling to recognise emotion, and reliving flashbacks without realising it through intense negative feelings and trauma responses.

These emotional flashbacks occur when something reminds a person of a traumatic event, and their body responds as if the trauma is taking place, even though they know they are safe.

She said: “I really struggle to connect logically what I’m thinking and physically what I’m feeling.

“You don’t even mentally associate feelings with trauma, and that’s something that lives with you much longer even when you’ve had therapy.”

Sophie is in her first stable relationship for a long time. She said she sometimes feels uncomfortable, or becomes scared that her partner doesn’t love her, which she describes as self-sabotage.

“Any time that happens, the urge to go out and completely destroy my relationship, for no valid reason, is huge.

“It’s something you fight every day.

“I’m more scared of myself because I know what my capacity for inflicting harm and distress on other people is because I’m out of control.”

Sophie had suicidal thoughts at university before she intermitted.

“I told my university, ‘I am unstable.’

“I went to the counsellor and she was like do you think about it, and I was like obviously I think about it.

“I think about doing very questionable things.”

Sophie feels her university did not do enough to make sure she was safe.

But she added: “I’m certainly in a much better place than I was nine months ago, and that is purely down to doing therapy once a week.”

Sophie can now identify if she is struggling when she isn’t checking in with herself regularly. Before therapy, she didn’t understand how her emotions worked.

“I’d get to the end of the day and be like have I had a good day? I don’t know.

“I couldn’t even tell you if I’d had a neutral day. I didn’t really know what a bad day was because every day I had no idea what was going on.”

Sophie puts her progress down to her therapist explaining the impact of unresolved trauma.

“All of the processes that were going on were explained to me scientifically, which no-one had ever bothered to do before.

“I understand why I’m behaving this way, even if I can’t always get myself out of it.”

Sophie still worries about how CPTSD might affect her relationships with others.

“What if I lose control and then everyone hates me? What if I choose to push people away?

“Will they understand that this isn’t really something I have control over all the time?

“Sometimes my behaviour isn’t me, it’s a continuing trauma response that I deal with every day.”

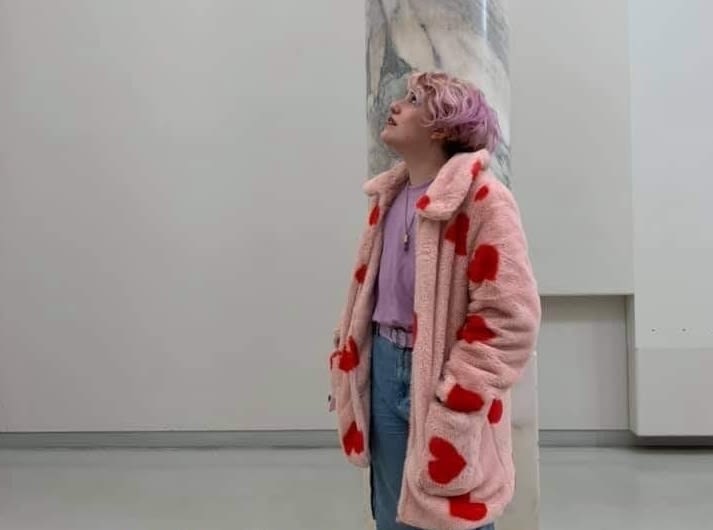

Emrys' story

Emrys first heard about CPTSD when attending a clinic for pain management, after being diagnosed with Fibromyalgia.

They described being unable to recognise or put labels on their feelings and thoughts.

“For some other people it was quite a straightforward thing: when I’m in pain I feel like this.

“I can’t put words to things in this straightforward way that other people are doing.

“I had a freak out on that first day, thinking I can’t do this, because I was finding it so stressful.”

The psychologist present took them aside and, after speaking to them about their history of trauma, suggested they might have CPTSD.

As a teenager, Emrys was in an abusive relationship. They have few memories of the trauma, which they say makes it harder to relate how their body responds to the abuse.

Emrys was advised to refer themselves to the Psychological Wellbeing Service at the hospital.

After two telephone assessments, they were told their trauma was too complex for the NHS to treat.

“It upset me but it upset me on a sort of displaced level, where I knew this isn’t really about me.

“What happens to everyone with more complex trauma than mine?

“It makes me deeply sad to know that experiences of prolonged abuse at developmental stages are common in the general population, yet there is just nowhere to go.”

Emrys has now started EMDR, a trauma therapy which aims to help trauma survivors reprocess memories, through their employer’s private health insurance. But they had to research their condition and therapy options on their own.

Emrys explained a disconnect between their body’s ability to feel, and their conscious recognition of those feelings.

“I don’t really have a filter, even though I very rarely will talk about this stuff without crying.

“But I just anticipate that. I am like ok I’m crying now, I am feeling emotion, I will just keep talking.”

They said: “[CPTSD] is not feeling able to be honest with feelings because of worrying about the impact of those feelings on other people.

“It’s getting stressed at situations that other people wouldn’t get stressed at and not even consciously realising it.

“Feeling like I have to be a perfect person, and if I’m not, there is some big yawning chasm beyond that. Losing perspective in terms of consequences for things.”

Emrys is polyamorous, and described the effect of CPTSD on past relationships: “It brought a lot of stuff up that I was a little bit aware of but I was suppressing as it went on, because I was finding it was making me feel panicky. I would just ignore it.

“I can’t untangle something that I can’t remember, I can’t consciously work through stuff from the past as I can’t remember it.”

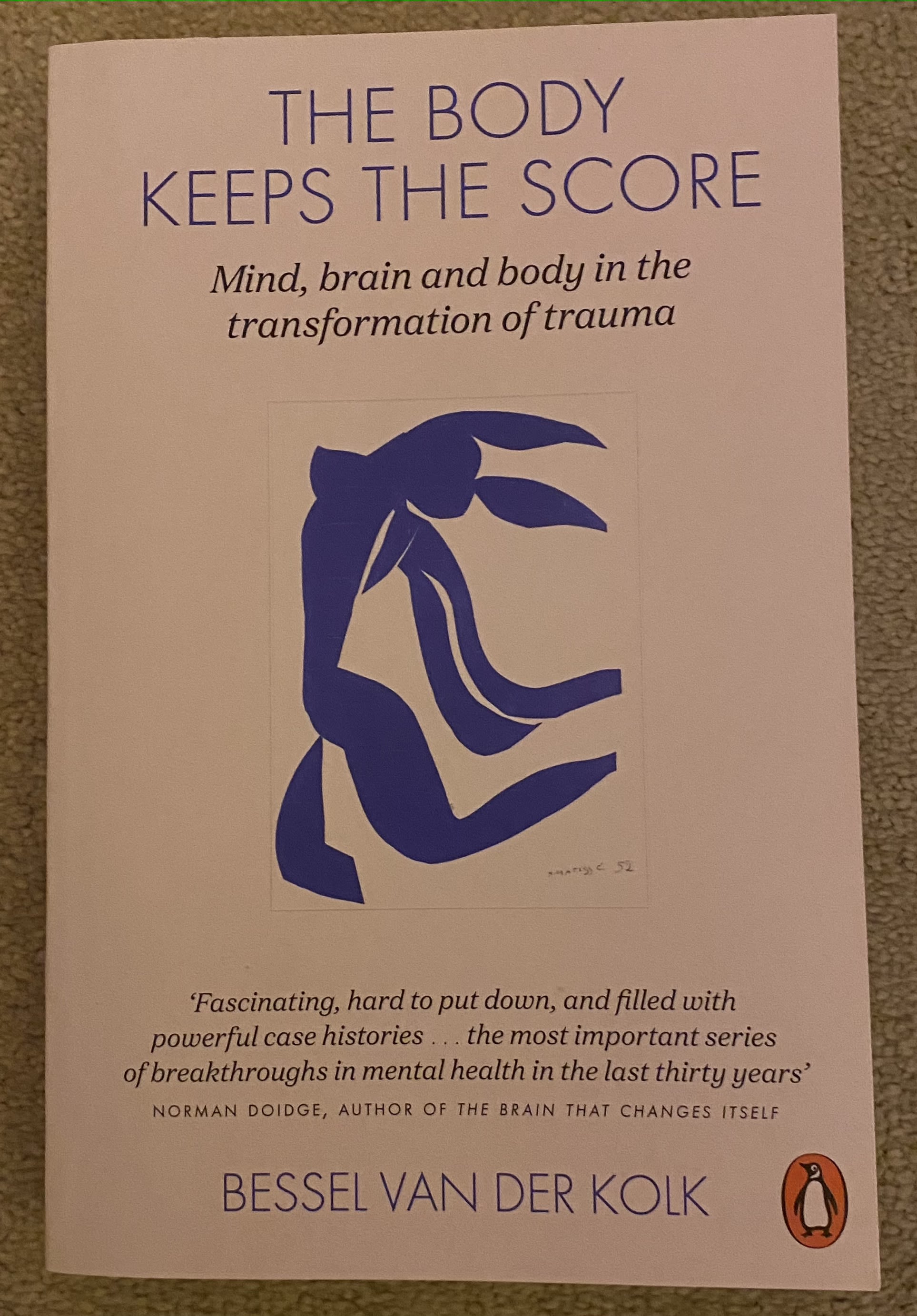

Emrys praised The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van Der Kolk. This book is the main source of information for people with dealing with the effects of trauma to understand what is happening to them.

All those mentioned in this article brought up the book. It deals with remembered and suppressed trauma, and case studies on how PTSD and CPTSD emerge in day-to-day life.

Traumatic events are stored differently by the human body and mind, and until they are able to be processed in a safe way, the body will react as if it is experiencing trauma whenever it is reminded of it.

Emrys said: “When we experience things and our brain’s trying to protect us from the fact of those experiences it stores it in different ways.

“That results in us becoming avoidant of things if we don’t reconcile these trauma memories.”

Emrys is now in a relationship they describe as the healthiest they have ever had.

“In our relationship I come across situations that trigger me because elements of them subconsciously reflect my abusive experiences, even though the context is completely different.

“But I am becoming better and better at recognising that and processing it properly.

“I can understand why and articulate it.

“I’m with someone who is not going to give me negative consequences for being triggered.”

They described it as real-life trauma therapy.

“That is the goal, to feel a thing, articulate the thing and reprocess it in a ‘you are now in a safe space’ context.”

Chen's story

Chen's name has been changed to protect their identity

Chen first discovered the existence of CPTSD on Tumblr eight years ago. They thought they might have it, but struggled to find any information about it.

The lack of information about CPTSD is a common thread in all these stories. Sophie, Emrys and Hannah also told me they found out about it online.

Chen believes they have had CPTSD since they were 16.

“It’s quite hard to know what to do with it because if you go on the NHS website or the Mind website there’s not currently a recommended treatment for it.

“Most of the treatments are just to manage the things that are immediately unhealthy behaviours, which I feel like I am doing.

“Then just go to therapy for 30 years and then maybe at the end of 30 years I’ll be ok.”

Chen grew up with their parents, maternal grandparents and sister. Their maternal grandparents did not speak English, and although their parents can use English, they are not able to understand all colloquialisms.

Chen said: “It is important that I am Chinese.”

“It’s hard to communicate what I mean, it’s hard to communicate to people who are not Chinese. It’s all just a bit of a minefield.”

Chen said their sister was very emotionally abusive towards them for as long as they can remember.

They described leaving for university and becoming overwhelmed as they were exposed to different experiences.

“Before, I just thought life was so miserable.

“When I went to university it was weird because I was in a different environment that was not living with my family for the first time in my life.

“I realised over several years that my family is actually extremely weird and bad, and that there are other ways for people to be.”

At first, Chen was not sure whether they had CPTSD. One reason was that they do not have knowledge of themselves without trauma for reference.

“I remember reading stuff that was the diagnostic criteria and thinking I’m not really sure that I actually see myself in this. But I also feel like I do.”

“The causes of complex trauma in my life, that was my whole life from when I was born to right now.

“It’s who I am in every aspect of myself.

My life has been shaped by these traumatic experiences.”

All the interviewees said they avoid conflict in their day-to-day lives.

Chen said: “I will let anyone do anything to me. I’m always emitting good vibes, laughing and joking.

“Whenever anyone is unhappy that’s bad news for me.”

Chen has emotional flashbacks, which impact their relationship with their girlfriend. They said they find it impossible to discuss potential sources of conflict with her.

“We’ve had these interactions where she’s trying to have a conversation with a child. I can’t have the conversation productively.

“I’m just like ‘I'll do whatever you like’ and just cry. I can’t respond.”

Chen also finds it difficult to talk about their emotions.

They said: “I cannot identify what I feel or what I want.

“I have a lot of anxious thoughts, all the time, about if I am to blame for something or if people in my life actually hate me.”

They received six sessions of NHS therapy, but had to continue it privately, which they can only afford twice a month. They have not had any treatment for CPTSD on the NHS.

Chen wishes more people knew about CPTSD and medical professionals were more aware of it.

“Every time you mention it, you have to make the case for it to exist.

“The fact that people don’t know what it is makes it very easy to believe that things are fine and I’m just making it up.”

Hannah's story

Hannah's name has been changed to protect her identity

Hannah is an online tutor who graduated from university in July. She hopes to go into education policy.

Hannah has been in therapy for four months. On the day we spoke, her therapist suggested she may have CPTSD.

She said: “When I googled it I thought those symptoms don’t match up with me.”

But her therapist explained CPTSD is not always characterised by very severe symptoms which have a large impact on day-to-day life.

Hannah said: “She sees it as more of a spectrum almost, that you can have a milder version than what you’d understand from it if you gave it a google.”

Hannah first noticed something was wrong after she entered her first serious relationship, although she did not know it could be a sign of CTPSD until now.

She said she had issues with detachment disruption and questioned her interactions with him.

“I have to do a lot of catching myself, when I think I’m being rejected or he’s being critical.

“I have to stop myself from seeing everything he says in a negative light.”

She described detachment disruption as “feeling insecure, and really hypervigilant, looking out for things that were wrong in his behaviour, in his actions, and constantly waiting for rejection.”

Hannah said it wasn’t until about halfway through the relationship, when things started getting more intimate, that she noticed the issues.

As well as feeling insecure, she experienced sleep disruption with anxious dreams, sleeptalking and sleepwalking.

She said: “That’s when everything started coming to the surface and I started getting really anxious.

“It was just these recurring patterns, and I just realised there was something going on down there causing this fear of being abandoned.

“I thought I haven’t been through any type of trauma. Then I started really delving into my memories, and these memories started coming back.

“I just never thought about it before.

“I was scared of my mum when I was a kid.

“She was unpredictable, irrational. Her expectations were unrealistic. She treated me as though I was an adult.”

Hannah said her mum still has these behaviours.

She added: “My therapist keeps asking me where do you feel that in your body. Sometimes there’s a pain in my back or my chest that I haven’t even noticed until she asks.

“Sometimes it can take a while to notice the signs that your body is giving you.”

Therapy has helped Hannah, but she still has work to do.

She said: “My system just gets really overwhelmed in a moment of anxiety.

“Shaking off that fear of doing something wrong, that’s what I’m really working on.”

Elizabeth's story

I did not realise my upbringing was abusive until very recently. I knew it wasn’t “normal”, but patterns of abuse and neglect were all I knew.

My whole life had been spent considering the impact my actions had on other people, to avoid as much abuse and conflict as I could. I buried myself in my school work, and learned not to feel anything at all.

In my final year of university, I began therapy for a traumatic event that happened when I was 18. The abuse at home forced me to bury it, and I hadn't spoken about it with anyone in four years.

But when I started to unpack this trauma and its aftermath, it became clear I had a lot of distressing and suppressed memories from my childhood too.

I began having physical and emotional flashbacks, regular panic attacks and sleep disruption. I experienced bad periods of dissociation, as well as exhibiting reckless behaviours and an inability to know how I felt.

It was clear to one university therapist that I had experienced complex and ongoing trauma, and she suggested I might have CPTSD.

I had never heard of CPTSD. When I researched it, I was confused. I’d experienced trauma, but it all stemmed from one event. How could I have CPTSD?

As more memories resurfaced, I was forced to confront the abusive reality of my upbringing.

I began to realise I had no idea what made me happy, what I wanted or needed, or how to take care of myself emotionally.

The more I researched, the more things finally began to fall into place.