I don't know what I look like

Life with Body Dysmorphic Disorder

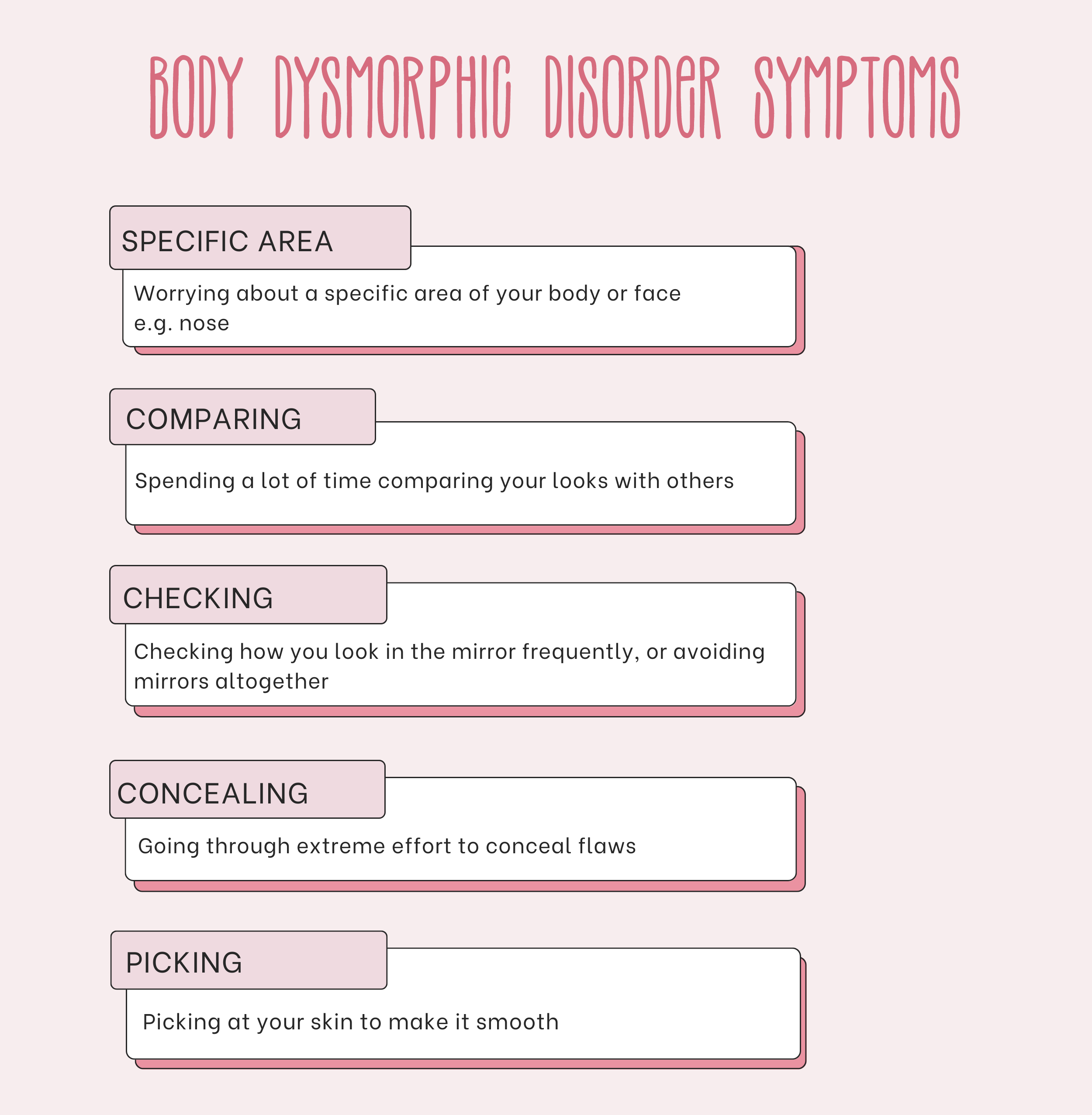

Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD) in simple terms, is when a person is worried about their appearance or specific 'flaws', which are often unnoticeable to others. The perceived flaw is usually not as prominent as the sufferer believes.

BDD is a serious mental disorder, which can cause devastating distress and interferes substantially with the ability to function in normal life.

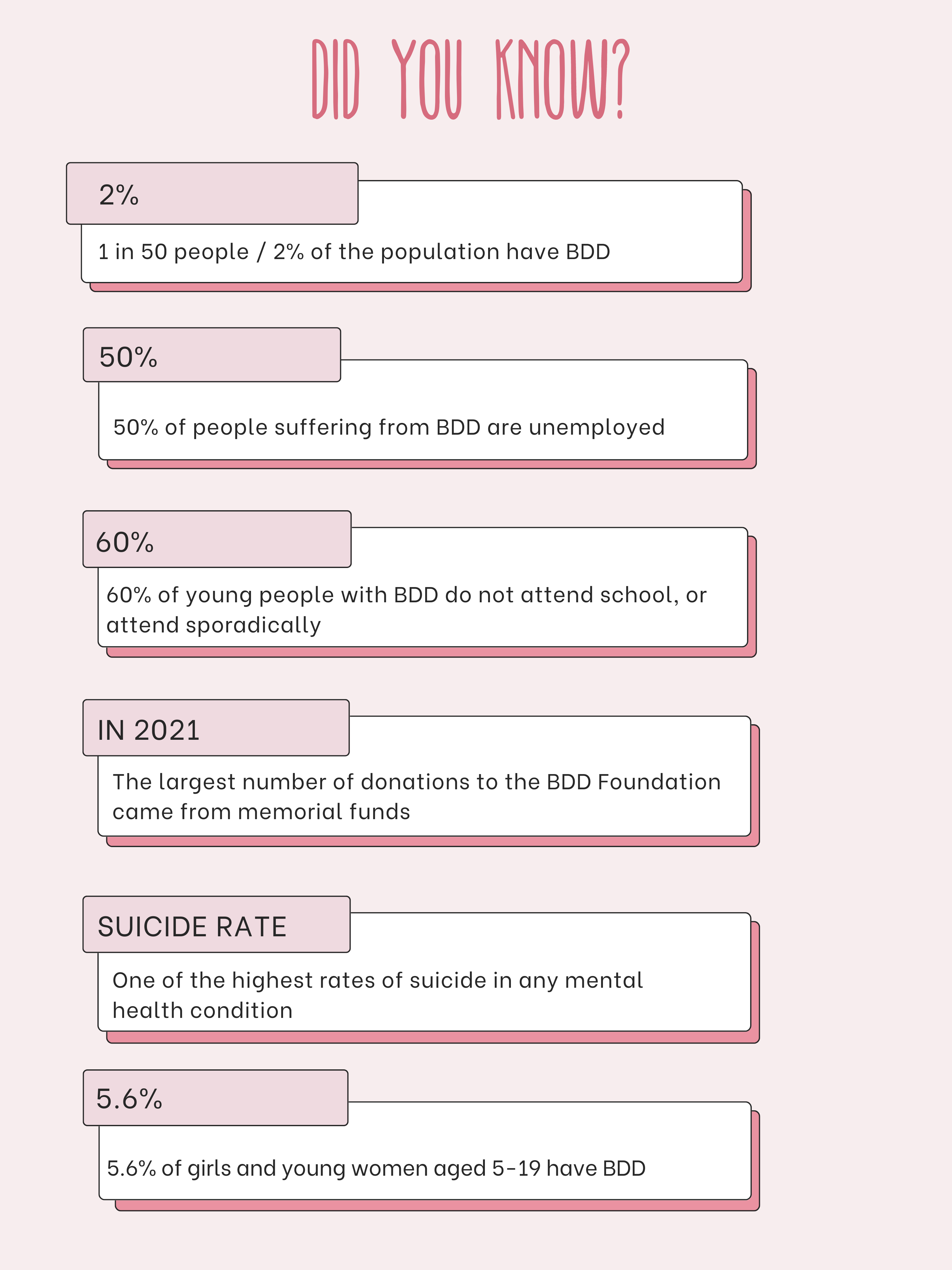

Although social media has become a positive tool for people to discuss their mental health and eradicate the stigma around it, however, it has encouraged a 'namedropping' culture, notably with body dysmorphia. So many people can relate to having insecurities around their appearance, but on TikTok particularly, creators frequently say 'My body dysmorphia is so bad', without realising the extremity of the disorder, which has one of the highest suicide rates of any mental health condition.

According to the BDD Foundation, there has been very little research into Body Dysmorphic Disorder, which urgently needs funding to develop a fuller understanding of it, and effective treatments. It is believed that BDD can develop due to a combination of genetic predisposition (nature) and environmental factors such as traumatic life experiences (nurture).

Dr Hana Patel, NHS GP and GP Expert Witness said: "BDD most commonly occurs in teenagers and young adults, affecting both men and women. It is a specific mental health condition and can seriously, including work, social life and relationships. It can also lead to affect people's daily lives depression, self-harm and even thoughts of suicide in some people.”

Patel confirmed that there is no direct cause of BDD although it is being investigated, and there are associations with other mental health conditions, such as OCD, generalised anxiety disorder or an eating disorder.

Evidence and research have also shown that people are more likely to develop BDD if they have a relative with BDD, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) or depression, and people who have experienced a traumatic experience in the past are more likely to develop BDD. For example, if they were exposed to abuse or bullying as a child.

However, BDD is absolutely treatable with the right help and support.

Patel said: “Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) can help people manage their BDD symptoms by changing the way they think and behave. CBT for treating BDD will usually include a technique known as exposure and response prevention (ERP), which involves facing situations that would normally make you think obsessively about your appearance and feel anxious, in a staggered way.

"Your doctor may also offer you medication, SSRIs - a type of antidepressant. There are a number of different SSRIs, but fluoxetine is most commonly used to treat BDD.”

Kitty Wallace, 35, is the head of operations at the BDD Foundation, and has suffered from BDD since she was a teenager.

Kitty had specialised CBT for BDD, involving exposure therapy where she had to gradually face some of her fears of leaving the house and reducing safety behaviours around her hair.

After this, Kitty got a lot better and was able to go to university and then get a job. However she had a major relapse in her late twenties when she became housebound again for nearly six months. Luckily, when she started a new course of therapy, she managed to pick it up a lot quicker than before, and her recovery has become more consolidated.

On recovery, Kitty said: "BDD is something I have to manage - it's something I've had for so long that I'm constantly trying to keep it at a good place and be conscious of my mental health. I'm running the BDD Foundation, I'm about to qualify as a counsellor, I got married - all of these things. I never ever thought I could live through it.

“Part of recovery is accepting that you are never going to be able to know what you look like, and trying to seek that certainty is a root to madness.”

Kitty makes reference to a study where researchers mapped the eye movements of someone with BDD as opposed to someone who doesn't and created an image of how they perceive themselves. For people with BDD, it's often very distorted.

She added: "The truth is that when we look at other people, we're not seeing them with our optical eye. We're seeing them with our mind's eye. When I look at someone I see all of their best features, their best qualities and my love for them comes through in how I view them, and so we are never going to be able to view ourselves the way other people view us. When I look in the mirror, my eyes hone in on specific things in detail rather than getting an overall view."

Emily Cohen, 30, first had body dysmorphia as a teenager, which started during puberty. She remembers feeling distressed by the stretch marks behind her knees, and from that point onwards developed a more distorted view of her body. For her, the stretch marks were signs of weight gain, and she became increasingly concerned about my physical appearance. This was the beginning of an eating disorder.

On the traumatic impact of body dysmorphia, Emily said: "I would often come home and cry at the thought of people thinking I was big. I would also catch myself in the shop mirror and think I looked huge. Body dysmorphia was a catalyst for the eating disorder and fed it throughout. Negative thoughts took over my mind and led me to believe my only achievement or life purpose was to get to a certain size.

"Physically, I was tired all the time. I would run every day, and when I didn’t have the energy, I would take long walks. Over time, I developed an immune disorder due to malnutrition.”

During her twenties and particularly the Covid-19 pandemic, Emily’s body dysmorphia shifted to her face.

She said: “I spent more time around mirrors or seeing myself on camera during meetings at work. I noticed flaws on my face that I became paranoid about. I’d spend hours each day analysing my face in different lighting, taking photos and calling my family asking for reassurance.

“I genuinely felt like there was something wrong with me. When I couldn’t get reassurance from friends or family, I would post on Reddit forums looking for a response that would prove that there was something wrong with my physical appearance.

"When I was told that there was nothing to worry about, the reassurance would last for a couple of hours before I’d catch myself in the mirror again and the cycle would repeat itself. This carried on for around a year, and it was incredibly debilitating because I felt like there was nothing that I could do to control how my face looked.”

Emily's body dysmorphia consumed her life and was an ongoing cycle of anxiety, trying to fix a problem, seeking reassurance, and temporary feelings of being okay but then back to extreme anxiety again. On the lack of understanding of its severity, she said: “I’m not sure if people who haven’t experienced it understand how it can make you feel mentally unwell. You perceive the world and yourself in a very distorted way. It can consume your life.

"I couldn’t understand why no one could see me the way I saw myself. The negative and unhelpful thoughts became stronger, and I couldn't separate them from reality. I would believe them rather than witnessing them and giving them no power."

Emily credits Psychotherapy, which she has been in on and off for years, with making her more self-aware and grounded. EDMR therapy in particular allowed her to process traumatic events instead of pushing down uncomfortable feelings and experiences.

She said: "Although therapy has never been specifically for body dysmorphia, it has come up in identifying the root cause. For example, I grew up in a chaotic home that often seemed out of control. Although my parents never meant to make me feel like this, I never felt good enough. I also have Jewish ancestry and experienced a lot of antisemitism at school. This made me feel wrong with my appearance.

"It takes time, but therapy has worked for me. I feel very grounded in myself and have a strong idea of who I am. My character and who I am are more important to me than what I look like. I wouldn't say that I feel 100% satisfied with how I look, however, I’m now very comfortable with myself and I feel the happiest I’ve been since I was a teenager.

"It’ll be a life-long process and I’m here for it. It's easy for me to say this now that I'm on the other side, but I’m genuinely grateful for experiencing body dysmorphia. It was my way of coping with traumatic events. Understanding this has helped me to accept it, especially when I feel that I lost myself and lost time I could have spent enjoying life.”

Lip fillers have become one of the most sought after cosmetic treatments

Lip fillers have become one of the most sought after cosmetic treatments

Dr. Deepa Panch (image credit: Kate Nielen)

Dr. Deepa Panch (image credit: Kate Nielen)

The rise of dermal fillers and non-invasive cosmetic surgery can be problematic for people with BDD.

Emily said: “During the pandemic, I considered lots and lots of different procedures. I spent hours researching facial surgeries. Luckily these are all expensive, so the research never went a step further. Also, when I was struggling with an eating disorder, I wanted to get surgeries that would help me to reduce fat in areas of my body. I also wanted calf reduction surgery.

“I have had lip fillers before. At the time, my lips were something I wanted to fix on my face. I compared myself to people I saw on social media. I felt that getting lip fillers would make me more acceptable, and for a while, I did feel better. Now, I don't feel that they suit me. Unless I get them dissolved, I will most likely always have some filler left in my lips and I’ve grown to accept that.”

However, surgery and fillers are not something Emily would consider now. Despite noticing a few changes here and there due to her face changing as she ages, she’s in a place of acceptance. Instead, she focuses on skin care to make her feel like she is taking care of herself without changing anything drastically.

Aesthetic and Surgical doctor, Dr Deepa Panch, recommends that people with body dysmorphia avoid getting cosmetic surgery. She said: “Studies have shown that surgery doesn’t actually help in the vast majority of cases and can actually make dysmorphia worse. In rare cases, patients will have undergone serious psychological counselling and intensive therapy before a multidisciplinary decision is made as to whether treatment may actually help but this is very, very rare.

“I have had patients come and see me, who in my opinion are exhibiting signs consistent with dysmorphia, who are unhappy with a previous treatment they have had. It’s very difficult as I will only see them after they have started a treatment journey, so you never know if this is something they have had for a while or have developed more recently. On the whole, they never feel better after their treatment, and in many cases, they feel worse.”

In Panch’s clinical practice she completes a BDD assessment with every patient, and has screening tools to highlight whether someone is at risk. Currently it is down to each individual clinic or practitioner to decide whether to do this, as there is no legal requirement.

Panch said that assessing for BDD is a complicated process and requires a definitive diagnosis to be made by a psychiatrist or a psychologist, but emphasised that all practitioners should be working towards this as we see the prevalence of BDD increase over time.

She said: “We have a duty of care towards our patients and recognising when not to treat is an important part of that.”

A distorted body image is a feature of both BDD and eating disorders, which also share many other symptoms.

Like Emily, my body dysmorphia went hand in hand with my eating disorder, once sitting with my body, before moving to my face, more notably my nose. Only recently, I went to see an aesthetics doctor to have a consultation about nose filler.

The subject of my mental well-being or medical history (other than allergies) didn’t come up, and eventually, I decided against it because one of the potential complications of putting filler in the nose is blindness. This, despite the very rare chance of it happening, was enough to scare me.

I had been taking pictures of my face from every angle, obsessively trying to contour to make my nose look slimmer. On a particularly bad day, I would avoid getting any glimpse of myself in the mirror altogether to avoid it ruining my whole day. The route of it all, like the feelings buried by my eating disorder, was that I was trying to take up less space in the world.

I was diagnosed with OSFED (otherwise specified feeding or eating disorder) when I was 15 years-old, after a year or two of very destructive and unhealthy eating and exercise habits, including excessive mirror checking and scrutinising every part of my body, being hyper-aware of how I looked from every angle. From that point on, I don’t think I’ve known what I actually look like.

Despite the fact that I've technically been in recovery since those teenage years, it was only when I had CBT at the age of 25 for both my eating disorder and body dysmorphia that I saw real progress.

My therapist helped me to see that my body dysmorphia is heightened when I am feeling emotional, tired or stressed - that when I can’t control an external situation, or I’m worried about something, my brain turns its focus to my facial features and I feel deeply insecure, and seek reassurance from loved ones.

Although the different types of exposure therapy exercises I had to do at the time were terrifying, CBT really changed my life for the better. I'm grateful to be in a much better place now, and like both Emily and Kitty, recovery is a lifelong journey that I'm invested in.

I’ve made peace with the fact that I might never know what I actually look like, have found freedom in food, and find so much worth and value in other aspects of my being.

As Kitty said above, with the right help and support, BDD is absolutely treatable.

For further information and support, visit: https://bddfoundation.org/

For support with eating disorders, visit: https://www.beateatingdisorders.org.uk/

Do you have BDD? Take the test

Before you take the test, it’s important that you note that:

- Only a trained health professional can make a diagnosis of BDD, although the questionnaire can help guide you and your health professional.

- The questionnaire assumes that you do NOT have a disfigurement or a defect that is easily noticeable. The judgment on how noticeable your feature(s) can be made by a health professional.

About the test

The questionnaire was developed by David Veale, Nell Ellison, Tom Werner, Rupa Dodhia, Marc Serfaty and Alex Clarke (2012) Development of a cosmetic procedure screening questionnaire (COPS) for Body Dysmorphic Disorder. Journal of Plastic Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery, 65 (4), 530-532.