#IAmNotDisturbing

The mental health activists calling on Instagram to stop censoring their healed self-harm scars

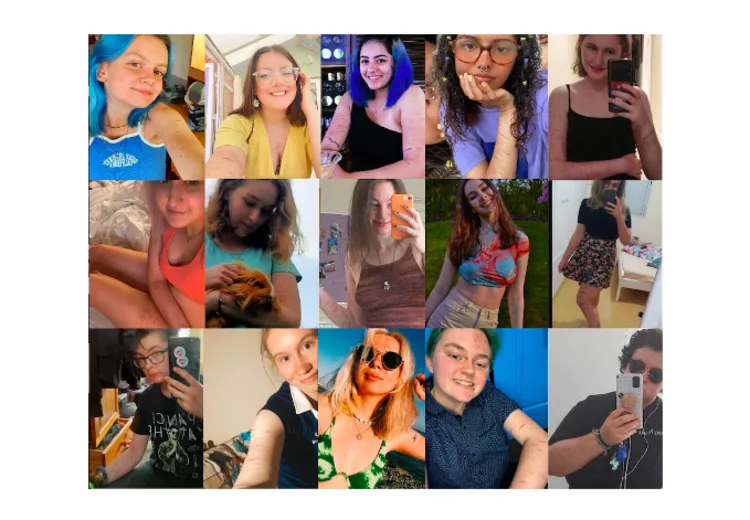

#IAmNotDisturbing, a petition calling on Instagram to stop censoring posts containing healed self-harm scars, has reached 4,000 signatures.

Usually, Instagram is notorious for lowering users’ self-esteem as they compare their lives to the curated highlights of others’.

For the mental health recovery community, however, this is not the case.

In this corner of Instagram, users show their highs and lows: they celebrate one another’s small victories (or ‘recovery wins’) and provide a shoulder to cry on in harder times.

It is a community which, for the most part, offers support and mutual understanding, as well as raising awareness of more taboo mental health issues.

The majority of its users are recovering from one or multiple mental illnesses, including eating disorders, personality disorders, and depression.

As part of their journey to recovery, those who have previously struggled with self-injury often post photos of themselves, which naturally include their healed scars.

They do not post these to glorify their illness or encourage others to replicate their actions, rather to show that it is possible to accept the past and move on.

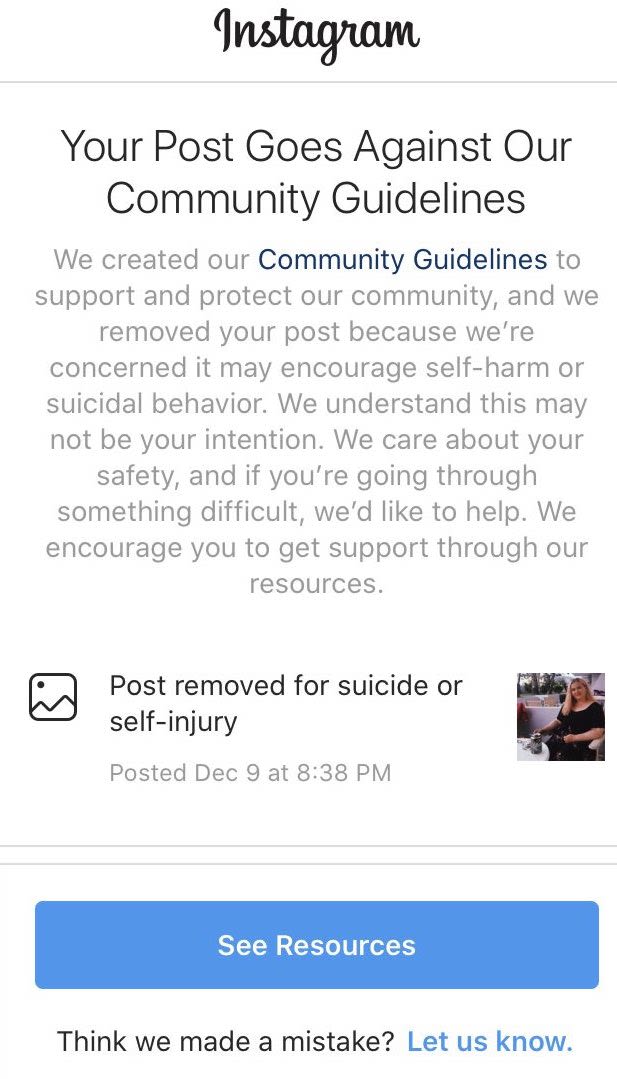

However, many users have found these posts either marked as 'sensitive' or removed entirely, prompting them to question why they are being tarnished with the same brush as those seeking to promote mental illness.

The petition was started by Tilly Bolton, 19, and her friend Rose Lidgely, 25.

Tilly has struggled with mental health issues for six years and set up her recovery account, @tillys.brain, to support others and educate the wider public on more taboo aspects of mental health.

She struggles to see how images of healed scars are different from surgical scars, for example.

“We just post photos of our bodies, we shouldn’t have to feel ashamed of them,” she said.

“It’s not attention-seeking, showing our scars isn’t promoting anything at all.”

She was particularly taken aback after a photo of her legs, which have healed scars on them, was removed.

It was a ‘typical’ legs-on-the-beach image, which she had seen posted by others many times before.

“It takes a lot for us to be proud of our scars, because every day just going out in public we get people staring and pointing,” she added.

“We face enough stigma and shame in our day-to-day lives and we come to Instagram to create this safe space and we can’t even have that.

“We can’t change anything and they’re just adding to the stigma.”

She highlighted how the community has been instrumental to her recovery in helping her feel more understood.

This feeling of acceptance was diminished through having her posts censored.

"We shouldn't have to feel ashamed.”

Lauren Curr, 22, runs their own mental health account and volunteers for the nonprofit JustANoteToSayHi, sending postal pick-me-ups to people struggling with their mental health.

They also felt that having their scars censored heightened the taboo surrounding them.

“Instagram is trying to censor our existence, but this is real and it happens,” they said.

“We’re already pushed aside by a lot of people and feel quite alone, so having a major media platform being like nope, you can’t be on here, just makes you feel like you can’t exist.

“It’s difficult when you’re trying to post a picture of you at the beach and it’s marked sensitive, because it’s not sensitive, it’s just existing.”

They highlighted how they feel empowered by seeing healed scars, both in real life and online.

“When I see them when I’m out, I feel a sense of solidarity, like I’m not in this alone," they said.

“Before, I just never, never saw myself in the future.

“So seeing people like me with healed scars that are in the future makes me think, yeah, there is a future for me, and it’s a positive one as well.”

This is a solidarity which translates into the online space.

Today I found out that @instagram has censored my posts, labelling a photo of myself as “sensitive content” and “upsetting”.

— Lara Ferguson 🇪🇺🌈 (@Lara_Fergie99) June 2, 2021

I cried because it affirmed exactly how I feel about myself - disgusted. AndI cried because I realised that I will never be able to escape this judgement. pic.twitter.com/jChMEjmd5S

Having the community so integral to their recovery tainted has been difficult.

“The recovery community is so strong, and I want to be motivated for recovery, not just for myself, but also for these people," they added.

“It’s like, these people believe in me. These people think I can do it, so I'm going to prove that I can do it.

“Having those people around you really helps.”

"It makes me feel like an outcast."

Sarah Derrick, 23, also changed how she uses the app after having photos taken down.

“It makes me very conscious of what I post,” she said, mentioning how some accounts go as far as to blur out their scars so that their photos are not removed.

“It creates a narrative that people with self-harm scars should be hiding away," she said.

“I know it’s a brutal way to put it, but it makes me feel like an outcast.”

She was hurt by Instagram labelling her images disturbing or offensive to justify their removal.

More recent changes, which now mean that posts of this kind are branded sensitive or graphic, still felt insulting and caused her to second-guess herself.

Any offer of support offered with the notifications of her posts' removal seemed almost irritating, and on some occasions, she was not informed at all that her posts had been taken down.

“I have to accept that this is who I am,” she added.

“You can’t censor my body when I’m out in public.”

The openness of the mental health community was instrumental in helping Sarah to accept herself, especially seeing those with healed scars living full, happy lives.

“It shows you that there is a life after self-harm.”