in isolation

Fifty years after London's Gay Liberation Front published its first manifesto, what does it mean to be queer in 2021?

Against a backdrop of laws which prevented LGBTQ+ people from expressing their identities, London's Gay Liberation Front (GLF) published its first manifesto in 1971.

The GLF had a set of demands for the government. The last was to afford the community a right: “That gay people be free to hold hands and kiss in public, as are heterosexuals.”

And their strategy was clear: “Singly or isolated in couples, we are weak – the way society wants us to be.

“Society cannot put us down so easily if we fuse together. We have to get together, understand one another, live together.”

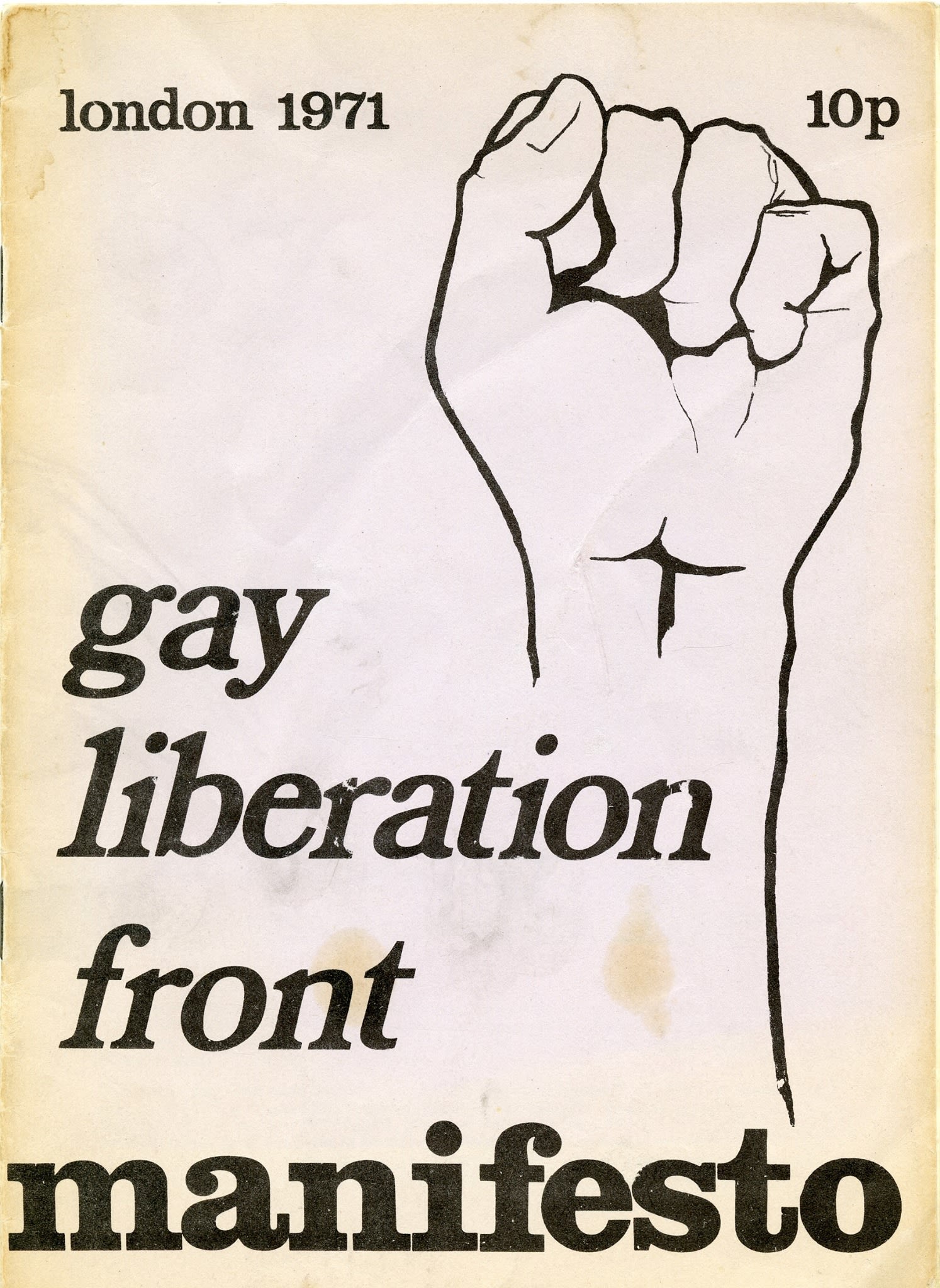

Gay Liberation Front Manifesto, 1971. Credit: LGBTQ+ Archives, Bishopsgate Institute.

Gay Liberation Front Manifesto, 1971. Credit: LGBTQ+ Archives, Bishopsgate Institute.

Josh, 19, moved to Camden from a village in Surrey in August 2020.

Josh, 19, moved to Camden from a village in Surrey in August 2020.

"I am not going to hop on Grindr to find friends, so there’s that main online aspect that I can’t do."

"I am not going to hop on Grindr to find friends, so there’s that main online aspect that I can’t do."

Fifty years later, young LGBTQ+ people are isolated once again against new backdrops – coronavirus lockdowns and a youth mental health crisis – and young LGBTQ+ people are now asking questions about how they can be out and proud in 2021.

“If you didn’t have your links already, it’s going to be harder to make them now,” 19-year-old Josh told SW Londoner when the third coronavirus lockdown began earlier this month.

At the time, Josh was looking to make new friends on a community Facebook group. They moved from the Surrey countryside to Camden in August 2020 to live with their boyfriend, but when the mainstream LGBTQ+ community in London was forced online for the third time earlier this year, they said it was becoming increasingly “alien” to them.

“Coming to London, I wanted to walk down the street looking a bit different and a bit funky but now, we can barely do that,” Josh said.

“Because of its LGBTQ+ heritage, the opinions of someone like me in London compared to the countryside are much more relaxed.

“I am also here in a relationship, so I am not going to hop on Grindr to find friends, so there’s that main online aspect that I can’t do. I want to be part of an adult couple with adult friends, but we don’t have that.

“I do feel like I’m missing out.”

It can be difficult to put a number on how many people feel “invisible” in the LGBTQ+ community.

But surveys from the first lockdown, which began in March 2020, show that Josh is far from alone in feeling isolated or lonely as a result of the pandemic.

One study, #Queerantine, by UCL and the University of Sussex found that out of 310 LGBTQ+ respondents, nearly 72% displayed some symptoms of depression. Loneliness was a factor in calculating some of the patients’ scores.

Another survey of more than 2,300 people by lifestyle magazine OutLife asked people whether they felt lonely before and during the pandemic.

Over half - 56% - of the respondents told OutLife they felt lonely, with only just over 20% saying they had similar feelings beforehand.

Within those figures, 67% of under-18s reported feeling lonely during the pandemic.

To make matters worse, the data – which were published in June last year - show 79% of OutLife’s respondents felt the pandemic was having a negative impact on their mental health.

The researchers at UCL and Sussex found that, although LGBTQ+ people were more at risk of mental ill health before the pandemic, the closure of LGBTQ+ social networks has exacerbated the crisis.

71.94%

of #Queerantine survey respondents showed symptoms of depression during the first lockdown. Loneliness was a factor in calculating patients' scores.

As venues and events are closed for business once again, what can young people do to stay visible?

West London-based poet, Troy Cabida, says lockdown gave him the space to write about things which came from an “introspective and inwards place”.

He even published his first pamphlet, War Dove, during lockdown.

“If you feel like you’re trapped, it’s not your fault. It’s really hard to take the weight out of your shoulders. To express yourself is something that you have to do for yourself,” Cabida said.

“I think it's all fuelled by the lockdown – the sense of alienation and finding out where home is.

“We are constantly told to stay home, but for a lot of people who have a challenged view of what home is, we don’t know where that is.”

Listen: Troy Cabida on isolation, identity and his new pamphlet, War Dove...

Troy Cabida on isolation in lockdown.

Troy Cabida on isolation in lockdown.

Those working in the support sector also say that being in lockdown has been alienating to them, too, but they are striving to create a sense of community online.

Faizan, who founded Imaan – a London-based support group for LGBTQ+ Muslims – says there is hope for the future.

They said: “There is a lot of comfort and support you can get from just being in the presence of another queer Muslim, and that’s obviously something we’ve lost for the time being.

“But holding events online, like our Ramadan event, allowed us to welcome queer Muslims around the world to our outreach. This was an amazing outcome which we weren’t expecting!

“Queer people are the same throughout the ages. We always try to look for community.

“I think that we’ll always find each other, regardless.”

Feature image: Flickr/LSE Library.