Algorave: the musicians coding electronic music live

Electronic music has always carried withit a certain strain of utopianism, suspended somewhere between Kraftwerk and post-industrial Detroit.

In a world mediated by technology on all fronts, it seems only natural that there is a movement of musicians cum computer scientists coding music.

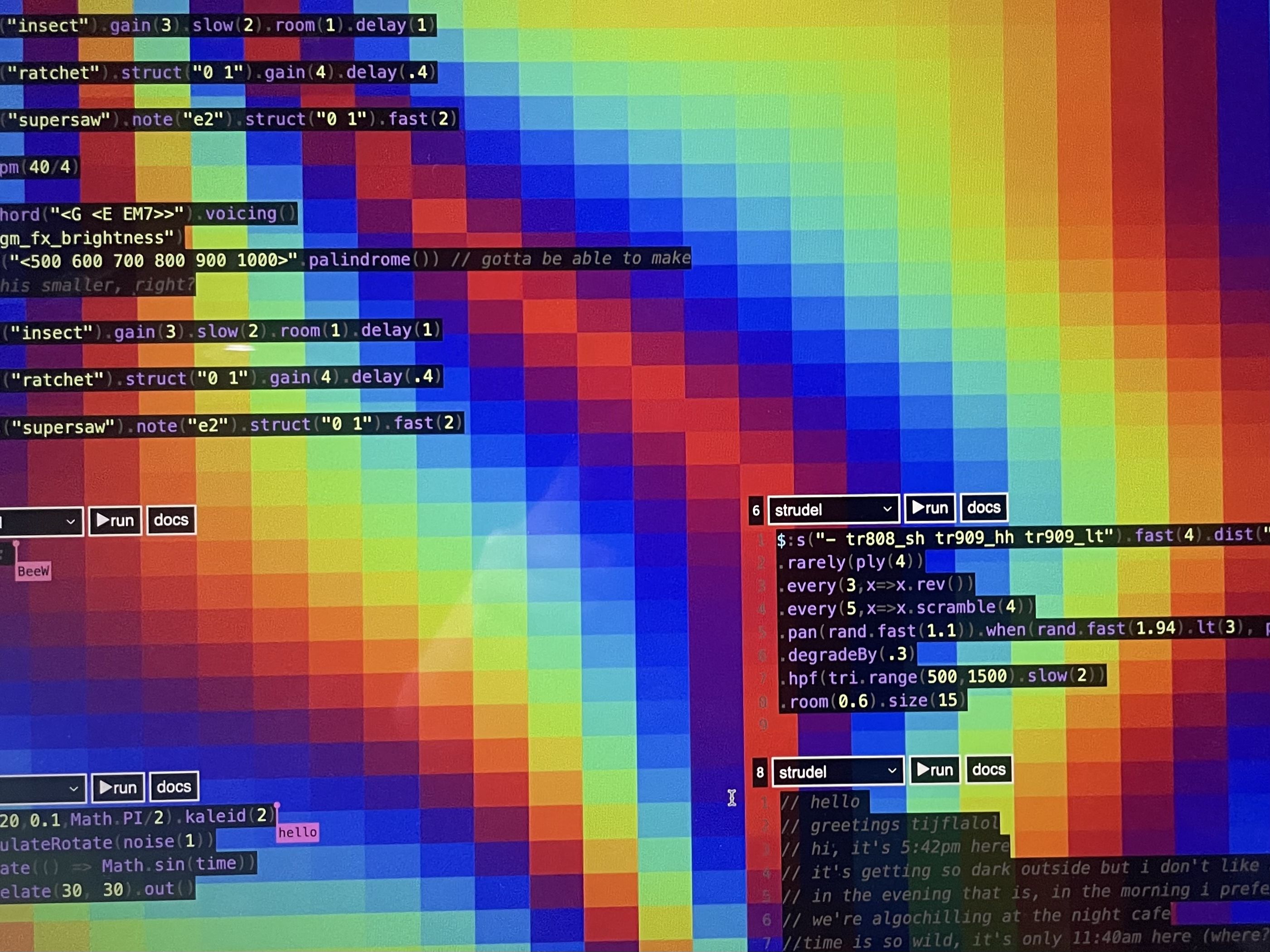

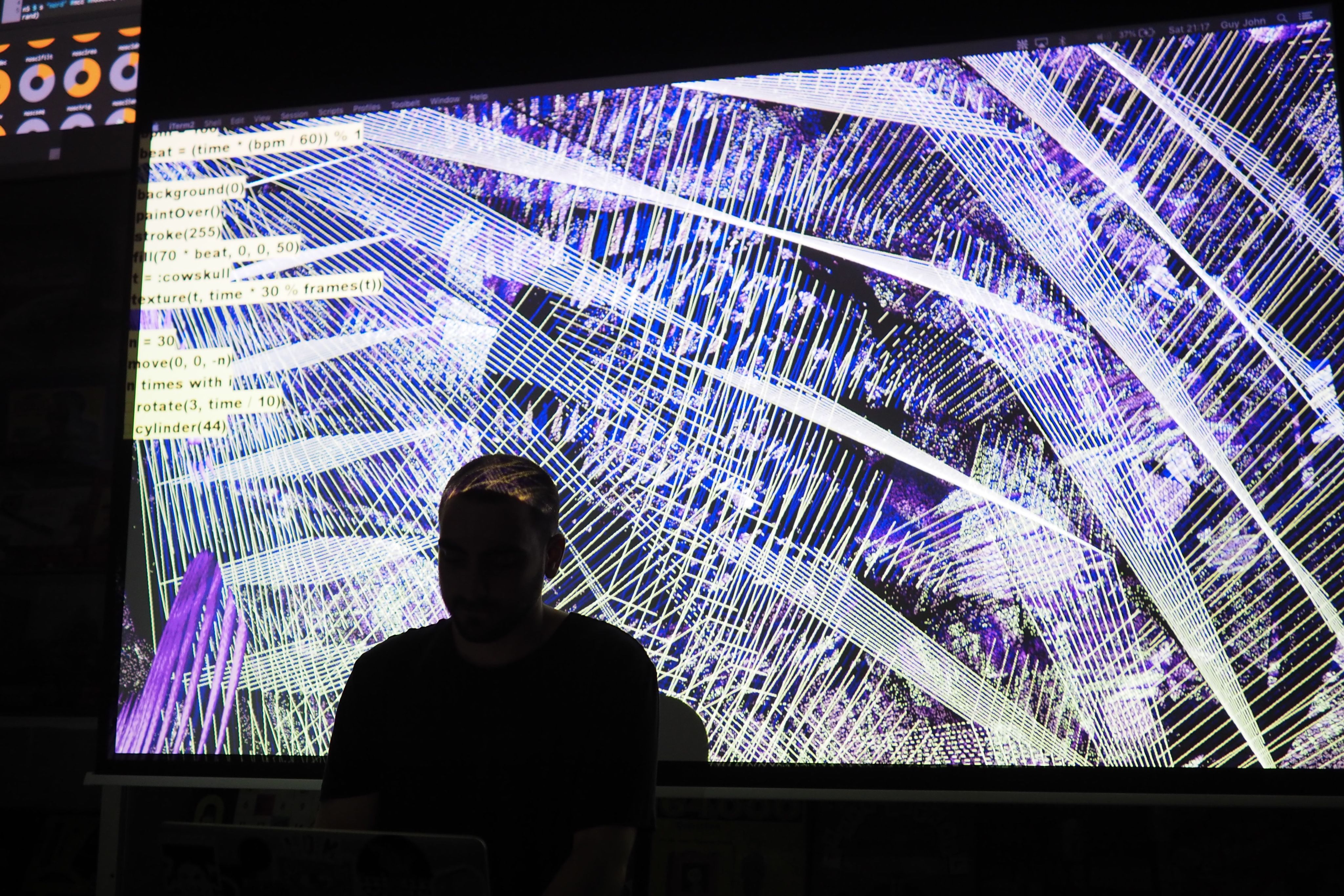

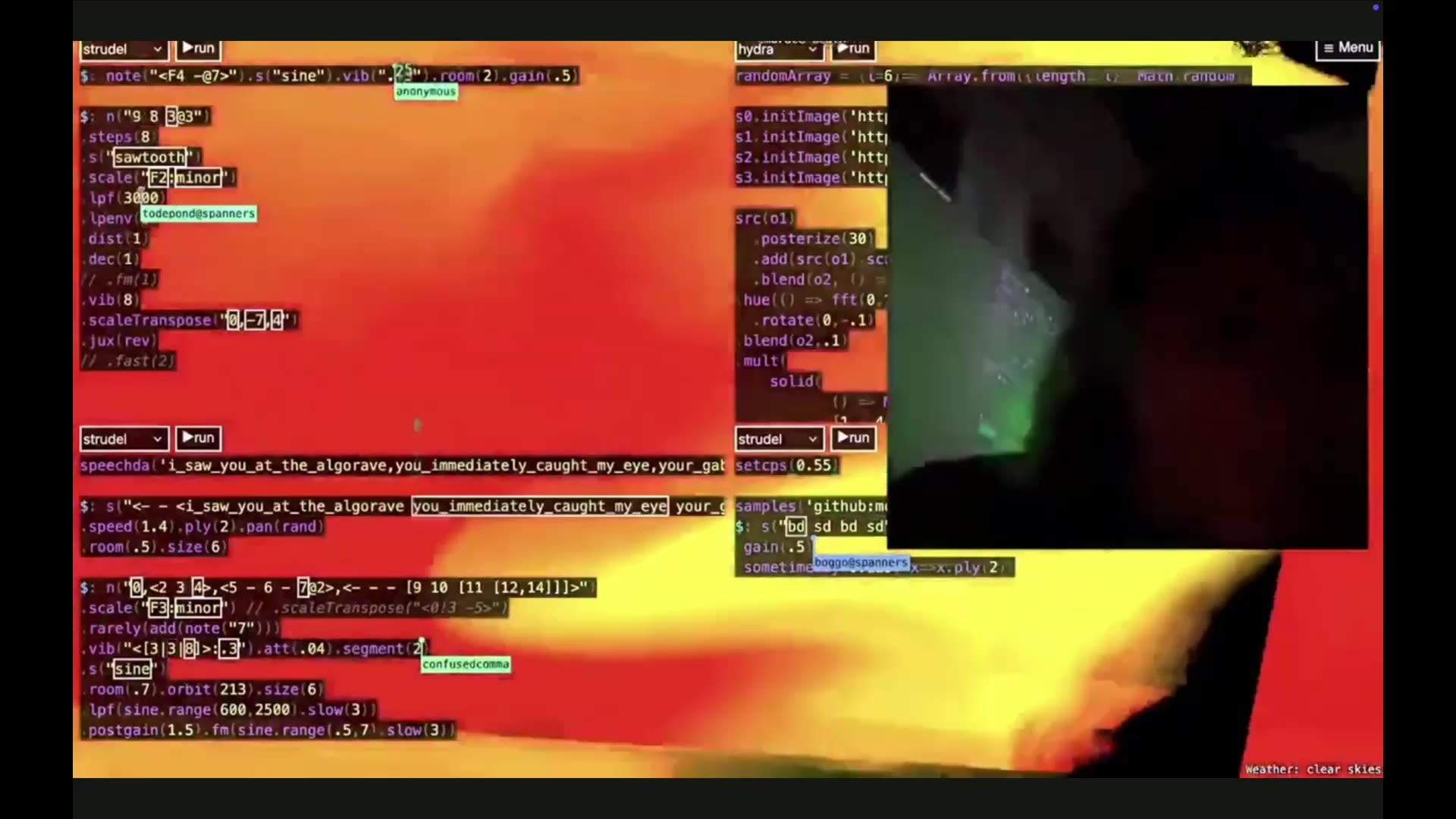

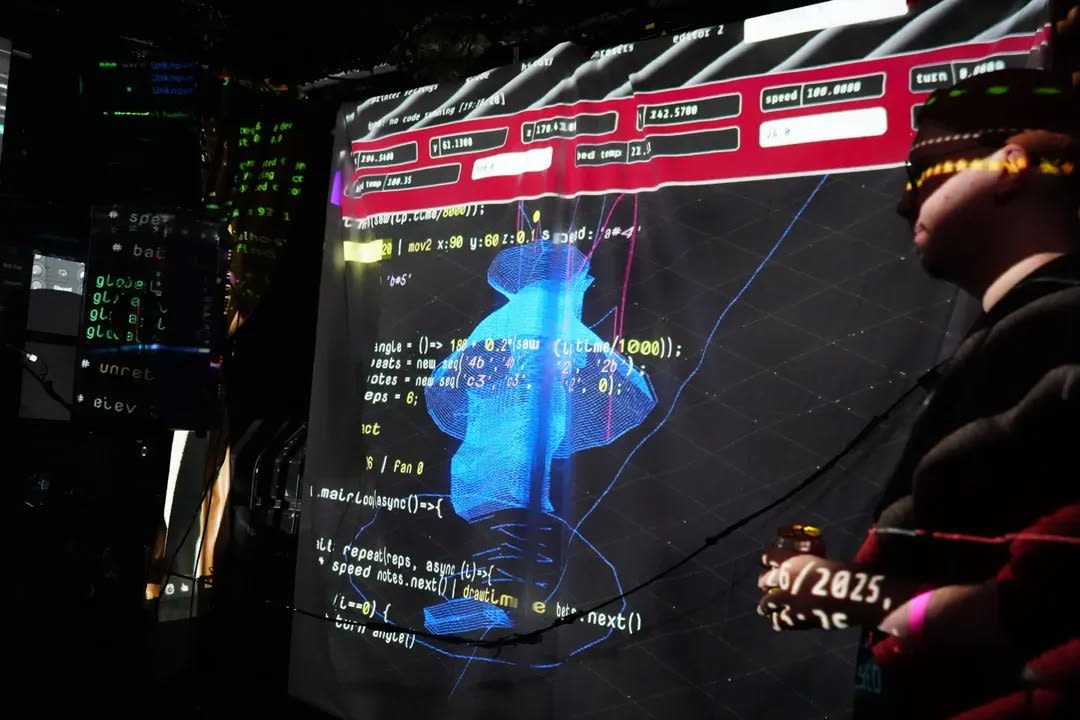

To live code is to use 0s and 1s to make people dance. Much like live jazz, live coders improvise music, writing new beats, melodies and rhythms as they perform, building up tracks from scratch.

While they code behind the decks, their screens are projected behind them for the audience to follow in real time.

Algorave was created in Sheffield in 2010 by Alex Mclean.

He coined the genre and created Tidal Cycles, an open-source music creation software that many people use to live code.

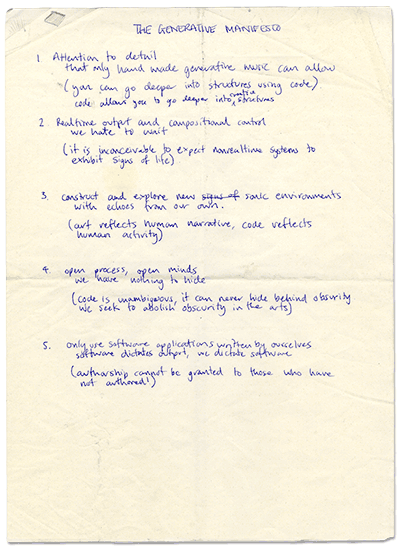

Algorave was founded on the specific stated ethos of openness, “open process, open minds,” which is part of Mclean’s 2000 manifesto on live coding.

It’s anti-copyright in nature; the focus on free-open source software and live improvisation runs against the hyper-commercialism of music as a product.

Algorave can genuinely lay claim to being not only its own scene, but an actual new genre of music. It has a uniquely low barrier to entry.

There are collectively-written guidelines for holding an algorave, which include principles such as “collapsing hierarchies” and “diversity in lineups and audiences”.

This stems from the fact that algorave grew out of music production and computer programming, programs that are famously not the most accessible or inclusive.

Sheffield is the true home of Algorave, but London is one of its key hubs, functioning less as a single scene and more as a loose network of artists, researchers, venues and DIY organisers.

Musically, the scene has remained deliberately eclectic.

Performances range from abrasive, glitch-heavy techno to playful, rhythm-driven sets influenced by grime, jungle and experimental club music.

But genre boundaries have long been porous, and innovation often comes from cross-pollination rather than strict stylistic rules.

Muscian and event organiser Daniel tells me that inclusivity has a practical function —by limiting the pool of musicans you’re effectively cutting out the talent, it’s counterproductive.

He also stresses that the community is lucky because it hangs off the coattails of people who’ve been doing it longer and in other parts of the country.

“The vibrancy and different ideas and approaches create a really good atmosphere; it’s practically a good idea.”

He likens the community to composer Brian Eno’s idea of a scenuis, which goes against the idea that innovation in art and culture comes from a few Great Chosen Ones.

Rather, great ideas emerge through a large group of people who make up an ecology of talent.

The draw of live coding is threefold: it’s creative, it’s nerdy, and it’s also incredibly social.

A brief history of electronic music

Alan Turing is best known as one of the world’s first computer scientists, but he was also one of the first people to see their musical potential.

While working at the Computing Machine Laboratory in Manchester in the late 1940s, Turing figured out he could make the enormous early computer produce identifiable musical notes by programming the CPU to play clicking at certain intervals while it spun.

Turing wasn’t particularly interested in creating music, but his foresight in programming the computer to create these tones was remarkable.

In 1958, the BBC created the Radiophonic Workshop, a laboratory for electronic music, tasked with adding an extra dimension to plays and other shows on Radio 3.

Using bafflingly complex equipment, its staff members were among the most progressive musical minds in the UK, creating the Doctor Who theme and sound effects for the Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy.

By 1964, fledgling engineer Robert Moog would unveil the first-ever electronic synthesiser, forever changing the history of music.

The Moog synthesiser looked like a cross between the controls of a spaceship and a telephone exchange; it was a system of modules that could be put in various combinations to produce otherworldly sounds.

Sounds generated by Moog synthesisers would become a staple of rock, jazz, disco pop and electronic music during the 70s.

By the early 1970s, these new electronic instruments began to move out of laboratories and studios and into popular music.

In Germany, Kraftwerk emerged with a sound that was deliberately synthetic, repetitive and machine-like, treating the synthesiser as the core of a new musical language.

Kraftwerk’s philosophy was that of reframing the relationship between humans and machines; Electronic music could reflect modern life, technology and urban movement itself.

It was almost as if to say, as soon as you enter a car, as soon as you train within a train, you’re in a musical instrument.

That idea found fertile ground in post-war and post–Cold War Berlin.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, abandoned power stations, warehouses and bunkers were repurposed into clubs.

At the same time, across the Atlantic, Detroit techno was taking shape.

Producers Juan Atkins, Derrick May and Kevin Saunderson drew inspiration from Kraftwerk’s futurism, funk’s rhythms and the industrial reality of post-industrial Detroit.

Their music imagined technology not as cold machinery but as a tool for transformation and escape, built on sequences, loops and programmed patterns.

Juan Atkins said: “Detroit is such a desolate city that you have to dream of the future to escape”.

This emphasis on systems, repetition and machine logic would later resonate strongly with algorithmic and computer-based approaches to music-making.

Unleashing Creative Potential

Despite its name, live-coding does not follow the logic of AI chatbots and large language models - it's not about automating creativity.

Most of the musicians I speak to describe how discovering live-coding had an expansive effect on their music.

It’s less a genre and more about using the computer as a performance tool.

Bogdan is a metal musician; he tells me how he used to produce entire metal tracks on his own, playing the guitar, keyboard, etc.

He would spend hours putting every single node in, mixing and mastering the track meticulously, a process he describes as creative but ultimately isolating.

Live coding has allowed him to make metal without being in a live brand; he’s been able to create “these kinds of grandiose, bombastic productions”.

Game designer by day, Bogdan discovered algorave at a hacker camping festival.

He was originally drawn to live coding because coding is something people usually think of as difficult or for very smart people, but it allowed him to see it as something you could do as art.

“There are ways in which you can design languages and coding tools that are accessible to everyone, because they sort of abstract the parts that are hard.”

Traditional coding languages like JavaScript are imperative, meaning you have to describe to the computer everything it has to do in order to achieve a task.

The opposite is true for a lot of live coding languages, which are declarative, meaning people specify what they want to make rather than how to make it.

“It’s a language closer to human speech, which is how people tend to conceive of AI these days – as a very natural language.

I tell the computer what I want, and it’ll do it for me. But this is cool in between, I’m telling the computer what to do in its own language – it's very goal-oriented.”

He also hasn’t recorded anything he's made in a year.

He says this ethos is typical of the live coding community, of creating something without attachment or the need to save it.

Daniel was a musician before he was a live coder, and he has found that live coding has unleashed him creatively.

It’s given him an entirely new way of looking at sound, which has been creatively liberating.

“Because it's all about numbers and keywords.

You don't get that kind the same kind of creative block, because you can always change and fiddle with things.”

“Even after going down the rabbit hole, and kind of thinking about things in very mathematical terms, I’ve ended up making the kind of music that I’ve been wanting to make for a long time.”

Laura is a software engineer who primarily does visual live coding using a program called Hydra.

She also organises a monthly live coding event called Algochill, held in an internet cafe in Shoreditch.

She was drawn to live coding because it allowed her to be creative and perform without actually being a musician.

“Through Hydra, I am basically following the steps of other people who have explored the use of analogue synthesisers via screen and have tried to translate the same concept via code.”

Her previous passions for drawing and painting drive her instincts for colour and form, and programming informs her understanding of basic mathematical operations.

London Community Laptop Orchestra

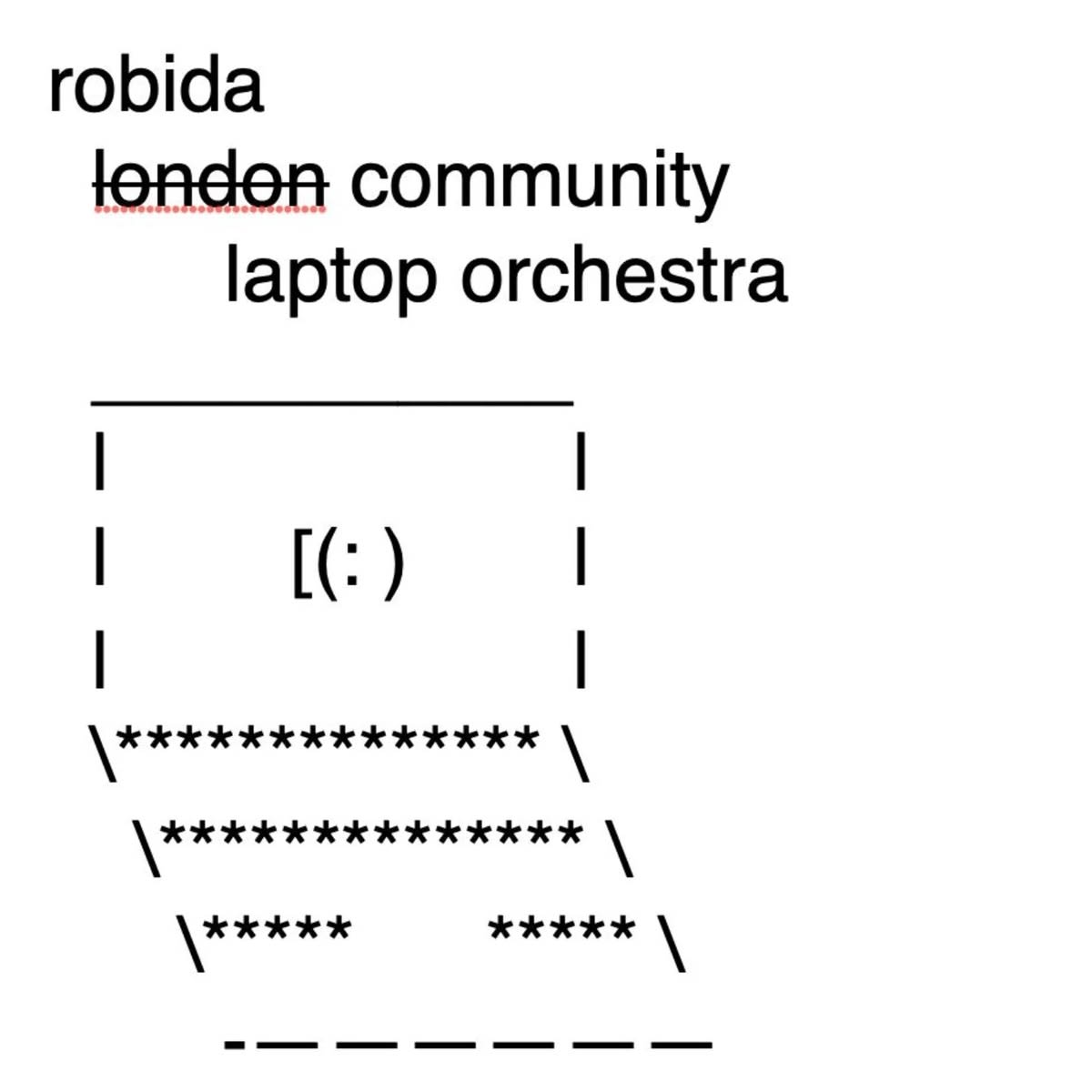

Running parallel to London’s algorave scene is the London Community Laptop Orchestra (LCLO), an ensemble led by composer, researcher and artist Kat Macdonald that approaches live coding and electronic performance as a collective social act.

It’s a guerilla orchestra (public performances without permission), inclusive of people who don’t know how to code or can’t play an instrument.

The accessibility and adaptability of the computer make it an ideal tool for performance.

It’s directly inspired by inspired by Cornelius Cardew’s Scratch Orchestra, founded in London in 1969 as an anti-elitist, experimental music collective open to trained and untrained musicians alike.

It was an experiment in democratic music-making, with participants ranging from civil servants to traffic wardens and labourers.

The idea is to get people curious about their technology and ask questions about how these technologies represent them.

Macdonald’s work thinks primarily about agency in relation to ubiquitous technology:

“There has been a change in technology from something that is so customisable to something that is frictionless.

"For example, in pre-2012 laptops, you could unscrew the back and take out the components; you used to be able to swap out the hard drive.”

“Simplicity and easy understandability have stripped away the kind of actually interesting things about technology itself or what it used to represent.”

Macdonald feels that there is an errant joy in having some friction with the things you are interacting with; this is the opposite of what we experience with technologies like ChatGPT.

They are more interested in having had the difficulty of having failed and what that teaches us about our own sensibilities — this is the kind of vulnerability that live performance opens us up to.

“It happened with music years and years ago with the convention of the backing track.

"It becomes a question of what live music is for. Is it to listen to an album played live in front of thousands of people?

Or is it to listen to a band playing their version of it at that moment and feeling the kind of energy of someone playing around with their own material?”

They were drawn to generative music and live coding with this ethos in mind.

Because it allows you to watch someone build a piece of music in front of you in real time, with knowledge that they’ve had to think about each component and what building blocks go where.

by Kat Macdonald via https://www.instagram.com/londoncommunitylaptoporchestra/

by Kat Macdonald via https://www.instagram.com/londoncommunitylaptoporchestra/