Institutional Racism in the UK Police

An investigation into the issue

Institutional racism in the police has existed in the UK for a century.

It was accepted that there is institutional racism within the police following the Macpherson report in 1999 on the police response to the murder of the Black teenager Stephen Lawrence. Since the murder of Stephen there have been numerous other cases of the police acting in an alleged racist way towards BAME individuals or groups.

What exactly is meant by institutional racism in the police and how can it be tackled?

On 22 April 1993, Stephen Lawrence, aged 18, was stabbed to death by a gang of white youths while he waited at a bus stop in Eltham, South East London with his friend Duwayne Brooks.

Brooks managed to escape the violent scene unhurt but Stephen collapsed and bled to death after being stabbed multiple times.

On the day after his murder, a letter with the names of the suspects, Gary Dobson, brothers Neil and Jamie Acourt, Luke Knight and David Norris was left in a telephone box. Police surveillance began on their homes four days later. The Lawrence family held a press conference on 4 May 1993 to express their frustrations at the police's attempt to catch Lawrence's murders and gained the support of Nelson Mandela in the call for justice.

Between 7 May and 23 June 1993 the police arrested all five suspects. Neil Acourt and Luke Knight were charged with murder on 13 May and 23 June after Brooks identified them at an ID parade. On 23 July 1993 the CPS said the ID evidence was insufficient so the prosecution was dropped.

In September 1994 Stephen's parents launched a private prosecution against Dobson, Knight and Neil Acourt. In April 1996 the murder trial against the trio failed with the judge ruling that Brooks' evidence was inadmissible. All three were then acquitted.

On 13 February 1997 the five suspects appeared at an inquest into Stephen's death and refused to answer questions. The following day The Daily Mail used its front page to show the five suspect's faces, inviting them to sue if it was wrong.

In March 1997 the Kent Constabulary launched its investigation into police conduct which nine months later highlighted "significant weaknesses, omissions and lost opportunities" - but no evidence of racial conduct.

In July 1997 the then Home Secretary Jack Straw announced that there would be a judicial inquiry into the murder and subsequent investigation. The inquiry was chaired by Sir William Macpherson, a retired High Court Judge.

The inquiry opened in March 1998 with the five suspects being told to give evidence or face prosecution. In October 1998 the Met Police Commissioner Sir Paul Condon apologised to the Lawrence family, who called on him to resign in July, admitting that there had been failures.

In February 1999 the Macpherson report was published. It accused the Metropolitan Police of institutional racism and made 70 recommendations, mostly aimed at improving police attitudes to racism. Also, of these 70 recommendations 67 quickly led to changes in working practices or the law such as strengthening the Race Relations Act.

In May 2004 the CPS announced that there is insufficient evidence to prosecute any of the suspects for Stephen's murder after a review. In November 2007 police confirmed that they were investigating new forensic evidence in the case following a police review that was launched the previous summer.

In May 2011 Dobson and Norris were put to trial over the murder of Stephen Lawrence after a review of forensic evidence. The Court of Appeal decided that there was enough new and substantial evidence to quash Dobson's earlier acquittal. In November 2011 Dobson and Norris' trial began and the jury heard that Stephen's DNA was found on the defendants' clothes. In January 2012 Dobson and Norris were both found guilty of murder at the end of a six-week trial into Stephen Lawrence's death. Dobson and Norris both received life sentences.

22 April is now celebrated as National Stephen Lawrence Day to commemorate the life of Stephen.

The case of Stephen Lawrence can be seen as the origins of institutional racism in the police in the UK but the Metropolitan Police claim to have made improvements since then.

Simon Fisher, spokesperson for the Met, said: "Over the years the Met has undergone enormous change and learning, implementing improvements and recommendations from reports including the Lammy Report and the Stephen Lawrence Inquiry report to make us a more effective and skilled police service.

"This is not the same Met as it was 20-25 years ago. We have improved how we investigate and respond to crimes; how we engage and work with our communities; how we develop and support our own staff and have made huge improvements in becoming a more representative workforce."

What is institutional racism in the police and what are the causes?

Before diving further into institutional racism in the police it is important to understand what the term actually means and know why institutional racism in the police exists.

Maurice McLeod, director of the anti-racism organisation Race On The Agenda, said: "The whole problem with institutional racism is that it's really hard to unpick. It's not about individual incidences or in the sort of stuff that's quite easy to pick out, the bad apples. When you talk about institutional stuff you're talking about how an organisation is set up and what it's there to do."

He said that historically the police was set up to protect the wealthy, protect the status quo, defend property and defend those in status. The police's role has certainly evolved since then but he argued that if you look at what the police put resources into and what they don't put resources into it leans toward what he calls 'social control'.

He gave the example of recreational drugs. He said that those with less money are more likely to be caught taking recreational drugs and that's where the police's focus is. He stated that it's not because the police hate poor people or Black people, but because the police are rewarded for the number of arrests they make and the easiest arrests are going to be in a place where people are probably on a lower income.

I also spoke to Dr Roger Grimshaw, Research Director at the Centre for Crime and Justice Studies (CCJS).

He said: "I think that first of all we have to decide what it is that is institutional about the racism and I would argue that it’s a combination of practices and attitudes within an organisation that produce persistent and widespread effects so when we talk about root causes we have to look at the whole structure and the expectations and the way in which policing like other institutions is embedded within a society that has systemic racism.

"We have to look within and outside because we know for example that there is racism in several parts of the criminal justice system."

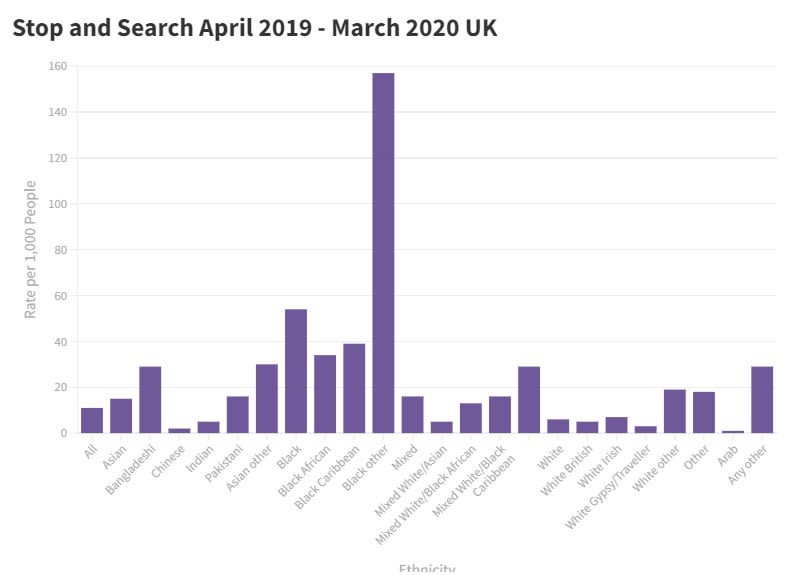

Data from https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/crime-justice-and-the-law/policing/stop-and-search/latest

Data from https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/crime-justice-and-the-law/policing/stop-and-search/latest

One of the issues resulting from institutional racism in the police is higher stop and search rates for BAME groups compared to White ethnic groups.

Government statistics for stop and search rates per 1,000 people in the UK between April 2019 and March 2020 show that the rate was highest for Bangladeshi and Black ethnic groups. The stop and search rate was highest for Black people.

The statistics show that there were 6 stop and searches for every 1,000 White people compared with 54 for every 1,000 Black people.

Dr Grimshaw said: "As far as stop and search is concerned it is a power that is discretionary so it can be used on the street in interactions without the reason being entirely clear. It's a power that can be used in unjustified ways.

"The overall effect can be traumatic for people who are being stopped and searched on the basis of what is quite thin reasons.

"The nature of the power is something that has to be taken into account and what we see then is this institutional effect in which prejudicial assumptions are brought to bare that certain kind of young people who look a certain way and appear on the streets regularly will be possessing drugs."

Mr McLeod elaborated on why the rate is so high for Black people.

A recent case of potential institutional police racism is the incident involving Child Q.

On December 3 2020 a Black 15-year-old girl, known as Child Q, was strip searched by police at her school in Hackney while she was on her period and even made to remove her sanitary towel. However, the incident only became known in a safeguarding report in March of this year.

School staff were concerned that she smelled strongly of Cannabis and may have been in possession of drugs, prompting them to call the police.

Two female police officers strip searched her without another adult present and without the school informing her family. No drugs were found.

The Local Child Safeguarding Practice Review, conducted by City and Hackney Safeguarding Children Partnership, found the strip search should never have happened, was unjustified and racism 'was likely to have been an influencing factor'.

The police has since apologised for the incident. Commander Dr Alison Heydari of the Met's Frontline Policing said: "It is truly regrettable and on behalf of the Met I reiterate our apology to the child concerned, her family and the wider community."

Mr Fisher added: "Policing is complex and challenging and we strive to ensure we are fair and just. Where we get it wrong we welcome scrutiny and where there are complaints we take these incredibly serious and expect to be held to account for our actions, including through investigations by the Independent Office for Police Conduct."

Scroll down to hear Mr McLeod's reaction to the incident.

So, what is the solution for tackling institutional racism in the police?

1. DIFFERENT RECRUITMENT

Dr Grimshaw said that he feels that the recruitment of BAME police officers only goes so far unless it can produce new leaders who will help to educate the whole police force.

He added: "It seems really important to start to recruit people who have experience in voluntary services or welfare or health and not to look for people who are from security role backgrounds. I would be looking for a different kind of recruitment."

2. ACCOUNTABILITY & SCRUTINTY

He also said:"It’s clearly very important for greater accountability and scrutiny, looking at practises and assessing outcomes. Although the police have had various kind of external advisors that help them, when I have spoken with a number of them they’ve been quite sceptical about the role or scope of the role of these external advisors. I just think it’s really important to reward the critical assessment and innovation and to learn from health and social services."

He said that one question that is asked is 'why is the police the default 24-hour service for mental health crisis's?' He believes that alternative services should be developed and that it's about strategic orientation - starting off by looking at how important it is to develop an organisation that has a clear strategy for improving health and wellbeing and reducing harm in London.

3. ACCURATE GANG DATABASES

Dr Grimshaw and his organisation, the CCJS, has placed a lot of emphasis on gang databases and he said that there are a lot of documents and reports about the Gangs Matrix which show how it has been developed in a disproportionately racialised manner. The Gangs Matrix is a database of suspected gang members in London and it was launched by the Met Police in 2012.

Dr Grimshaw said: "It’s meant to provide information to the police about who is involved in gangs but it's extraordinary how disproportionate the number of Black individuals has been in this database and despite featuring heavily in these databases, young Black and minority ethnic people are not responsible for the most serious violence in their areas."

He said that if a police officer in London wants to find out who's in a gang they go to the Gangs Matrix and as a police officer it's very hard to avoid that. The Matrix is an institutional base of information and an example of what he calls a kind of organisational bias which builds up throughout the organisation and influences practice because it's organisationally sustained.

He stated: "If you want to change policing you have to change the organisational manifestations that unite and organise the whole of the police body and I think that the gang databases are a classic example of what we would refer to when we talk about an institutionally racist structure."

Mr McLeod also gave his thoughts on how institutional racism in the police can be tackled.

Stephen Lawrence image from 4WardEverUK via Flickr under CC BY 2.0 license https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/