Is the right to protest being eroded in the UK?

A look at the current state of British activism

Protests have surged in the UK over the past few months, especially in the capital. Environmental action, anti-racism, LGBTQ rights, better working conditions, anti-monarchy sentiment, refugee rights, and recently the freedom of Palestinians are protests most Londoners will recall seeing recently on the street or on TV.

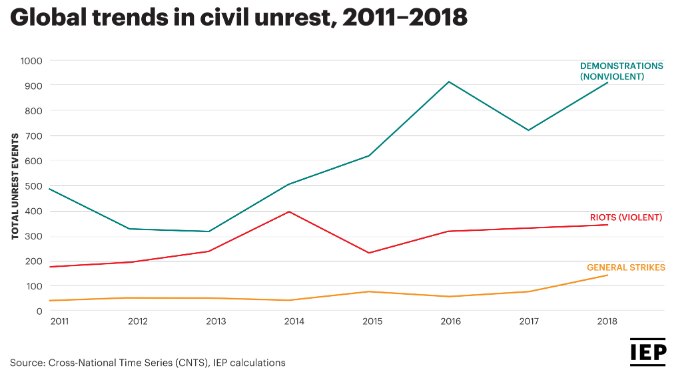

Seeing at least one every weekend has almost become a staple of the local culture. It is clear discontent with government policies regarding several social issues has increased globally over time, as shown by the 2020 Global Peace Index.

Dealing with these protests is a delicate and controversial issue for governments, with any form of action, or indeed inaction, being the subject of thorough scrutiny and harsh criticism from all sides. Earlier this year, decisions by the British government and behaviour shown by some of its ministers sparked these kinds of discussions nationwide.

Here, we will explore the government’s response to the recent increase in protests and the public response this has generated, with some insights into the Just Stop Oil and Palestinian freedom movements.

Image from the Institute for Economics & Peace's Global Peace Index Report 2020s

The law

On 15 June 2023, Parliament enacted regulations that amended the Public Order Act (POA) 1986 in a bill sponsored by former Home Secretary Priti Patel and Lord Sharpe of Epsom. The changes included the creation of protest-specific offences and an expansion of police powers to stop and search with or without reasonable suspicion.

Patel’s successor, Suella Braverman, also used the government’s “Henry VIII powers” to reduce the threshold of disruption that warrants imposing restrictions from “serious disruption” to a “more than minor hindrance or delay”. This change had previously been rejected by the House of Lords, prompting Braverman to use the powers to circumvent the chamber’s decision.

Legal experts have expressed concerns that the bill’s vague wording may result in excessive subjectivity being involved in police decisions to arrest people. It has also sparked debate as to whether the bill breaches articles 10 and 11 of the European Convention on Human Rights (freedom of expression and freedom of assembly), which was incorporated into the Human Rights Act, 1998.

The 2023 act added section 7 and amended sections 12 and 14. These prohibit interference with national infrastructure, give officers the power to impose conditions on marches, and allows the Transport Police to remove whatever assembly they deem trespassory. Crucially, these last two sections rely on the judgement of possibly a single senior officer, chief officer or chief constable.

A Home Office spokesperson said: “The right to protest is a fundamental part of our democracy but we must also protect the law-abiding majority’s right to go about their daily lives. That is why legislation is in place to clarify the definition of serious disruption and give police the confidence they need to clear roads quickly.

“This legislation was voted on by both the House of Commons and House of Lords, following proper parliamentary procedure.”

The reaction

Curiously, looking up the act on social media will mostly bring up backlash. Given the usual amount of comments celebrating protester arrests in social media, one may assume a significant fraction of the public would support the act.

However, the amendments have received criticism from all sides, with critics questioning the intentions behind the bill as well as perceived bias from the police when applying the law.

It is clear the ambiguity of the Public Order Act has increased tensions between the public and police, regardless of political alignment.

Protester voices

Activists across different movements have criticised the amendments and emphasised that it will not deter them from continuing to protest. In fact, many of them expressed feeling that organised action was even more warranted.

At a Just Stop Oil talk at University College London, where supportive professors let the group speak to students worried about the climate crisis. There, they talked about their experiences and attitudes towards protesting.

One of its organisers, Sam Holland, 21, shown in this Instagram post spraying paint over the University of Leeds, said: “Young people should be out in the streets breaking the law and getting arrested for doing so because it is the right thing to do at this point in history. It is the just thing to do, I am not being radical in doing that.”

Sam is currently facing prison time in early 2024, having been charged with climbing on a gantry on the M25 motorway last November.

Another JSO organiser, Will, 26, said: “We are going to march, and when the police say ‘you’re causing disruption and need to leave the road’, we will say ‘if you want us to do that you’re going to have to arrest us, because we have a right to protest in this country’.

“The plan is to fill up the police cells, to occupy all their time and capacity. We’re going to shut down the police in this city.”

Regarding Sam's statements in the Instagram post, the University of Leeds issued the statement: “We are taking a robust approach to tackling the existential challenge of climate change, with a £174 million Climate Plan which includes our target of delivering net zero emissions by 2030.

“Our policy on responsible investment is to invest in companies that are sustainable and that purposefully set out to solve the problems of people and the planet profitably, without benefiting from causing harm to the world.

“We do not invest in companies that are materially engaged in certain sectors, including thermal coal, the extraction of fossil fuel from tar sands, oil and gas extraction, production and refining."

The effects

This bill seems to have further driven a wedge between the public and the police. It is increasingly common to witness many arrests in a single protest, accompanied by chants of shame on the police.

Officers are faced with ever tougher situations to manage and harder decisions to make, relying on what many consider to be poorly drawn legislation to do their jobs. As people respond and more movements arise for different causes, the threat of an overwhelmed police force becomes more and more likely.

In this video, police are shown to follow a handful of JSO organisers to a pub after a march was fully dispersed. Eventually, an argument arose about the validity of scientific evidence on climate change.

A spokesperson for the Met said: "Officers know they are expected to remain impartial and professional at all times. We are aware of the video and will be reminding the officer of this."

For now, we may have to get used to considering the ever more complex and surreal situations we routinely face when groups invoke their right to be heard.