Kevin Willmott

An activist of small towns

and silver screens

There are two sides to Kevin Willmott. One writes films, wins Oscars, and works with Hollywood superstars like Spike Lee and John David Washington. The other teaches in a small Kansas town, laughs at his own jokes, and enjoys nothing more than kicking up his feet to the TV.

The two worlds collide on the walls of his small office at the University of Kansas. Framed movie posters meet shelves packed with books on film and race, alongside various knick-knacks like cameras and Academy Awards. His desk is as messy as they come.

“I’m real good at zoning out in front of the television; that’s probably what I do best,” Willmott laughed, leaning back in his chair. But finding time to relax doesn’t come easy. “It’s been a really busy year,” he said.

“The kind of work you do in film, you’re working for others and there’s always challenges and things you have to overcome and contend with. It keeps you real busy.” This comes on top of his full-time teaching job, but Willmott admits this is the easier side of his workload.

“I wish I could say it’s harder than it is. I just enjoy it that much,” he laughed. That’s why, even after winning an Oscar for BlacKkKlansman in 2019, Willmott was back teaching in Kansas just two days later. “In the end it’s all about the work. The work is where you find meaning and where you find purpose,” he said.

“Coming back after the big ceremony, and going back to work, it was a great reminder for myself and hopefully it told my students something too.”

Willmott took his Oscar home and shared the glory with colleagues [Credit: University Daily Kansan]

Willmott took his Oscar home and shared the glory with colleagues [Credit: University Daily Kansan]

Teaching more than just course material is important to Willmott. He’s as much an activist as he is a screenwriter or teacher, and when a new state law allowed students – on a campus where cigarettes and alcohol are banned – to carry a firearm, he couldn’t keep quiet.

On an otherwise ordinary day in 2017, instead of his regular jumper and jeans, Willmott came into class wearing a bulletproof vest. “You try to ignore that I’m wearing a bulletproof vest and I’ll try to ignore that you could be packing a .44 Magnum,” he told his students.

Campaigning against gun violence in a Republican state poses certain risks, of course. “I got some death threats,” Willmott admitted, “but that’s to be expected in the world of America these days.”

Knowing such people exist is actually part of the motivation. “That’s one of the reasons you want to step out and do it, because you know it’s important,” he said.

“The people that want to keep things ignorant and backwards and regressive, those people don’t want you to step forward. They want to make sure you keep your mouth shut.”

But staying silent is something Willmott will not do, and wearing the bulletproof vest wasn’t his first time raising awareness of gun violence.

Willmott and Spike Lee’s 2015 film Chi-Raq is a musical drama about gang violence in Chicago. As the film opens, “THIS IS AN EMERGENCY” flashes on screen before chilling statistics are revealed: 2,349 Americans died in the Afghanistan War between 2001 and 2015; 4,424 Americans died in the Iraq War between 2003 and 2011; 7,356 Americans were murdered in Chicago between 2001 and 2015.

Filmmaking is another form of activism for Willmott, and while Chi-Raq warns against gun violence throughout, statistics like these make the issue blatant. Just like his students, Willmott hopes that people watching his films will take away something deeper. “That’s definitely the goal,” he said. “We’re trying to share something that’s truly important to us, that we’re hoping becomes important to them too.”

Expressing his views on such a large scale is intimidating though, as a film viewed by millions extends far past Kansas’s borders. Hate mail and online trolls are normal.

“That just goes with the territories,” Willmott said. “You have to count the cost of these things before you step out, before you make your statement or show your feelings about something. You shouldn’t think you’re going to step out and that people are going to love you.”

The film that brought him the most attention was BlacKkKlansman. Based on a true story, it follows Ron Stallworth, the first black officer in the Colorado Springs Police Department, who went undercover in the Ku Klux Klan. While it shows and explores the blatant racism present in 1970s America, Willmott’s activism again seeps in as the viewer is left with horrific scenes of the racism still prevalent today.

A reel of haunting clips is shown before the credits, of the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, where self-proclaimed members of the alt-right branded assault rifles and swastikas to solidify America’s white nationalist movement.

It shows the modern-day KKK marching through the University of Virginia with torches; it shows when James Field Jr ploughed his car through a group of peaceful protestors, killing one and injuring 19; it shows then-president Donald Trump saying that the violence was equally the fault of black Americans. There exists an illusion that racism is no longer a problem, but as a black man in the United States, Willmott has “seen it become a lot worse.”

His own activism also began in the 1970s as Willmott grew up in what he realised was a heavily segregated place. He was born in Junction City in 1959, a city in north-east Kansas of just 20,000 people, but as a black boy it felt even smaller.

In high school he joined a programme that helped underprivileged teenagers find jobs, and was offered one at the Junction City Fire Department. “This fireman was my boss, and he brought me round to where the firemen live one day. He said, ‘you’re the first black person we’ve ever let up here.’ There had never been a black firefighter in Junction City.”

Willmott soon moved away to study at Marymount College, just 45 minutes down the road. After four years he received a Bachelor of Arts in drama and returned home to a city still wrought with racism. “I got out of college in 1984 and it was still that way. It was still segregated,” he said. “I just felt like somebody needed to say something about that.”

Willmott became deeply involved in activism there. “I helped to create two homeless shelters for folks in Junction City and I spent about five years working on issues there,” he said. “It taught me a lot about politics and about racism and discrimination and how society works.”

Campaigning on a local level is very different to the activism Willmott blends into his films. “You pay personally a lot more [in a small town]” he said. “People will come after you and they’ll come after your job and livelihood and reputation. There’s very little protection in that world for you.”

Despite the dangers though, “all of those things have influenced me in my writing in various ways,” Willmott said. “I think when you pay personally for things you believe in it has a deeper effect on you. That’s what I learned through that whole period, and so when I write about those things, I have felt some of it, so hopefully that helps in understanding them.”

That’s what drew Willmott to direct the upcoming documentary No Place Like Home, which combines his love for small town activism with filmmaking. Based on the book by CJ Janovy, it follows members of the LGBTQ+ community as they campaign for their own rights in Kansas.

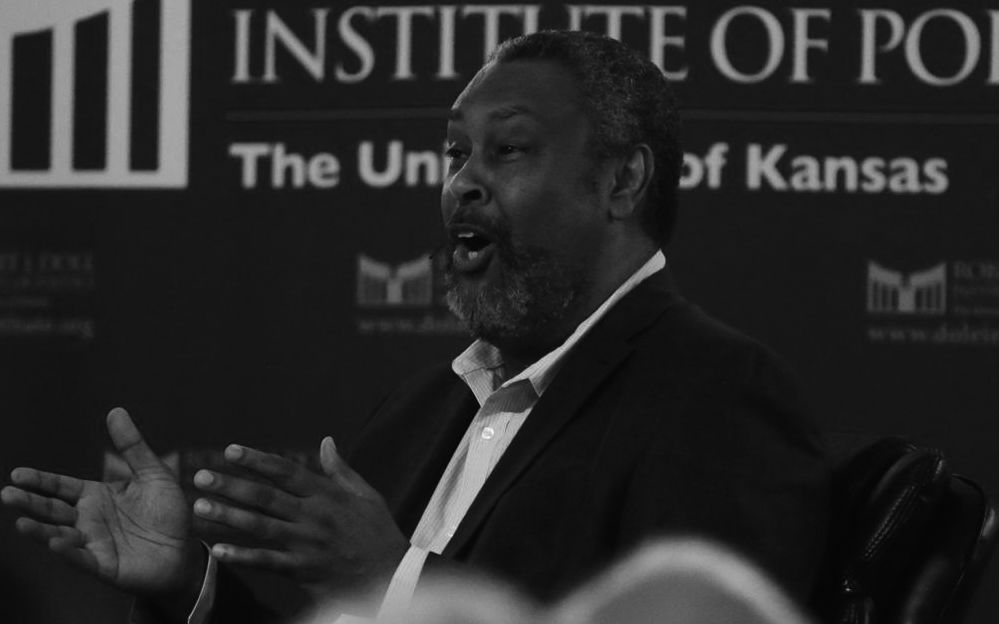

Willmott giving a speech at his university [Credit: University Daily Kansan]

Willmott giving a speech at his university [Credit: University Daily Kansan]

“CJ wrote this great book that told these stories that reminded me of myself in Junction City doing the activism,” Willmott explained. “It’s another example of a hidden group of people in Kansas. People know there’s a lot of gay people here but they don’t hear from them very often. We’re hoping to tell that part of the story.”

No Place Like Home is a fitting name for why Willmott was interested in the documentary. Although he’s worked in many major US cities, “the fact I grew up in Kansas is a big thing for me. It’s left its mark,” he said. “I love visiting those places and I love going there to do work, but I like coming home where life’s a lot easier.

“You always care about what’s going on back home,” Willmott continued. “Spike Lee, for instance, he’s a New Yorker,” and John David Washington grew up in sunny Los Angeles. “Your hometown, your home state, I think if it means something to you then you shouldn’t deny that.”

No matter how many Oscars he wins, or how celebrity he becomes, Kevin Willmott will always come home to Kansas.