An explosion of violence: knife crime in the pandemic

By Kat Pirnak

For many, knife crime has become synonymous with London. In the year leading up to the pandemic, the capital saw its highest rate of knife crime in a decade.

For a while, knife crime was an even bigger killer of under 25s than COVID-19. But as the nation went into its first lockdown, crime levels began to drop dramatically.

The reduction prompted Met commissioner Cressida Dick to call the falling rates of knife offences a “silver lining” to the pandemic.

However, data provided by the Office of National Statistics later showed that a substantial proportion of the reduction could be explained by the decreased levels of armed robberies.

On the other hand, rates of homicide and attempted murder during the pandemic remained comparable to previous years:

Knife crime has become synonymous with London. In the year leading up to the pandemic, the capital saw its highest rate of knife crime in a decade.

For a while, knife crime was an even bigger killer of under 25s than COVID-19. But as the nation went into its first lockdown, crime levels began to drop dramatically:

The reduction prompted Met commissioner Cressida Dick to call the falling rates of knife offences a “silver lining” to the pandemic.

However, data provided by the Office of National Statistics later showed that a substantial proportion of the reduction could be explained by the decreased levels of armed robberies.

On the other hand, rates of homicide and attempted murder during the pandemic remained comparable to previous years:

Who does knife crime affect?

Who does knife crime affect?

“Now, we have teachers reaching out to us saying they've got children as young as six carrying knives actively saying they want to stab someone.”

Lives not Knives CEO Eliza Rebeiro warned that there is now a significantly higher number of young individuals experiencing mental health issues.

She said: “A lot of young people that wouldn't have been referred to us previously were referred to us because they witnessed sexual violence or were exposed to substance abuse during the pandemic.”

The charity provides mentoring for young people as well as awareness training for teachers. However, due to restrictions, staff have not been able to work with as many people as before.

“What shocked me was that everyone was told to stay home and yet we still had 14-year-olds being killed,” she said.

“Now, we have teachers reaching out to us saying they've got children as young as six carrying knives saying they want to stab someone. We need to start supporting people from a much younger age.”

Eliza also expressed concerns about the influence of gang culture but maintained that school exclusion and untreated trauma remain some of the biggest problems facing young people today.

“There are many things that lead to the end result of a young person being killed,” she said.

“What we don't want to do is say that every young person that was killed or has carried a knife is in a gang.”

Eliza's message to young people:

Co-founders of Lives not Knives: Eliza (right) and Monique Rebeiro (left)

Co-founders of Lives not Knives: Eliza (right) and Monique Rebeiro (left)

Ben Kinsella/ Credit: Met Police

Ben Kinsella/ Credit: Met Police

“Social media desensitises young people and normalises violence.”

For Patrick Green, the CEO of the Ben Kinsella Trust, social media has become the biggest accelerator to knife crime in recent years.

The charity, which spreads awareness through interactive exhibitions, was established after 16-year-old Ben was stabbed to death during an unprovoked attack in 2008.

Patrick said: “The thing that’s changed the most since Ben’s murder is the negative influence of social media and how young people make decisions based on that information.

“Social media desensitises young people and normalises violence because there’s so much of it online.

"It has also made it easier for young people to be groomed by gangs who are often far quicker to get onto these platforms and engage with young people than youth services.”

“A lot of the stabbings we see now are in relation to stuff that was said on social media over the past six months.”

Criminology professor Simon Harding also believes social media played a “huge role” in the explosion of violence following the easing of restrictions in London.

Due to increasing poverty, he maintains that more areas in the capital have become susceptible to knife crime as the incentive to make money through illegal means continues to grow.

Simon explained that the pandemic has brought gangs closer to young people by exacerbating online issues such as grooming, the selling of drugs, and the creation of drill music.

“Social media has poured petrol on the flames,” he said.

“The pandemic has led young people to spend more time online and so a lot of the recent stabbings we see now are in relation to stuff that was said on social media over the past six months.”

In his research, Simon identified a troubling new pattern of behaviour in which young people now confront others by using the “stab on sight” tactic.

“As a result, young people are fearful of what lies in wait for them outside their homes. They view the landscape of London differently to adults and see it as very threatening.

"So some may feel they have to carry a knife in order to be prepared for what might happen.”

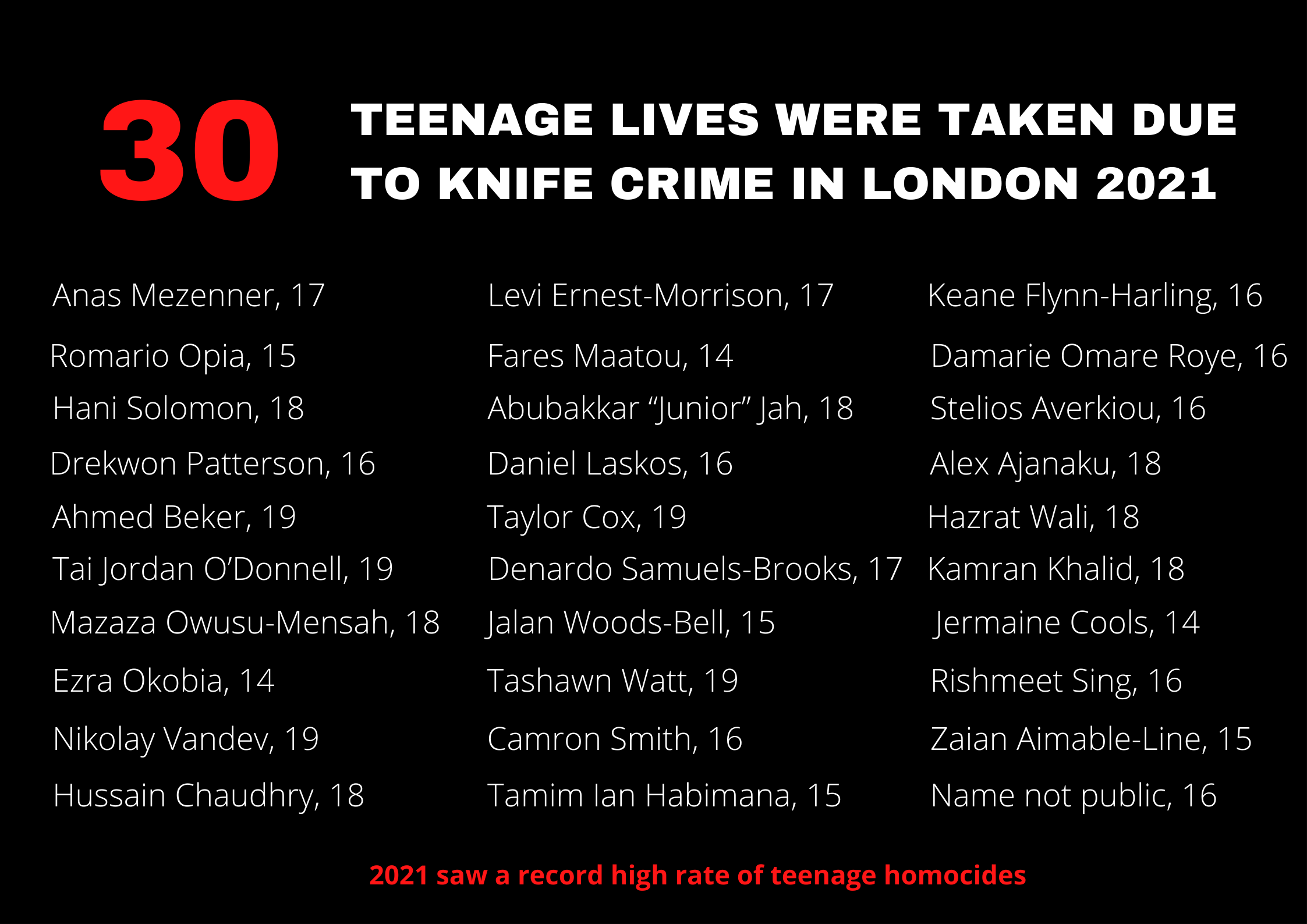

In the year that Ben Kinsella died, 29 teenagers were stabbed to death in London. For more than a decade, 2008 had the highest rate of teenage homicides in the capital.

It remained that way until New Year’s Eve in 2021.

Below is a map of gang territories in London:

Credit: UK-Drill

“A lot of the stabbings we see now are in relation to stuff that was said on social media over the past six months.”

Criminology professor Simon Harding also believes social media played a “huge role” in the explosion of violence following the easing of restrictions in London.

Due to increasing poverty, he maintains that more areas in the capital have become susceptible to knife crime as the incentive to make money through illegal means continues to grow.

Simon explained that the pandemic has brought gangs closer to young people by exacerbating online issues such as grooming, the selling of drugs, and the creation of drill music.

“Social media has poured petrol on the flames,” he said.

“The pandemic has led young people to spend more time online and so a lot of the recent stabbings we see now are in relation to stuff that was said on social media over the previous six months.”

In his research, Simon identified a troubling new pattern of behaviour in which young people now confront others by using the “stab on sight” tactic.

“As a result, young people are fearful of what lies in wait for them outside their homes. They view the landscape of London differently to adults and see it as very threatening.

"So some may feel they have to carry a knife in order to be prepared for what might happen.”

In the year that Ben Kinsella died, 29 teenagers were stabbed to death in London. For more than a decade, 2008 had the highest rate of teenage homicides in the capital.

It remained that way until New Year’s Eve in 2021.

Around 7pm on December 31, 15-year-old Zaian Aimable-Lina was stabbed to death in Croydon. Less than an hour later in a separate attack, another 16-year-old also died from fatal stab wounds.

The latter became the 30th teenager to be murdered turning 2021 into the deadliest year on record for teenage victims of knife crime.

Since the deaths of the 30 teenagers, Mayor of London Sadiq Khan pledged to invest almost £50 million into tackling knife crime.

In a statement, he said: “Every death from violent crime is heart-breaking, devastating families and communities.

"We know the challenges of the pandemic have exacerbated the causes of crime and violence and that’s why this investment is so timely.”

I am devastated by the deaths of a 15-year-old boy in Croydon and a 16-year-old boy in Hillingdon. My thoughts & prayers are with their families, friends & communities. I’m in close contact with @MetPoliceUK who are doing everything possible to bring those responsible to justice.

— Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan (@MayorofLondon) December 31, 2021

Zaian Aimable-Lina/ Credit: Met Police

Zaian Aimable-Lina/ Credit: Met Police

But there is still more to be done.

Patrick said: "The most important thing we need is a recognition from central government that this is a problem that extends beyond the life of any administration or prime minister.

"It should be like COP 26."

“The national government will, at some point, have to step up and do something about it,” agreed Eliza.

“But I think as a community we can also do so much more. So many people have been affected by this and many have already begun to step up by volunteering.

"It's the power of the people, not necessarily the power of government, that can make change.”

But there is still more to be done.

Patrick said: "The most important thing we need is a recognition from central government that this is a problem that extends beyond the life of any administration or prime minister.

"It should be like COP 26."

“The national government will, at some point, have to step up and do something about it,” agreed Eliza.

“But I think as a community we can also do so much more. So many people have been affected by this and many have already begun to step up by volunteering.

"It's the power of the people, not necessarily the power of government, that can make change.”

Sources and credits:

• Office for National Statistics

• Policy Exchange Report: Knife Crime in the Capital by Sophia Falkner

• Canva stock images

• The Met Police

• Drill UK: map of gang territories