Legal aid with South West London Law Centres

Why urgent reform is needed

Legal aid is not a sexy topic. It’s not a vote winner, nor does it spark debate amongst members of the general public. But as legal aid is a fundamental pillar of a functioning justice system, the apathy towards it is perhaps half the problem.

Parallels have been drawn between legal aid and the NHS. The latter is perpetually discussed and dissected, with every member of society ostensibly invested by a shared understanding that we all rely on it. But legal aid lacks a similar investment in part because no-one wants to think they’ll be embroiled in something requiring legal advice.

Ultimately we have a vested stake in a system we think we’ll need and therefore aim for it to function well.

Legal Aid is in Crisis: We Must Act. https://t.co/iAwAJm2HAz

— Robert Rinder MBE (@RobbieRinder) December 3, 2021

Since the introduction of the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act (LASPO) in 2012, the legal aid sector has had to survive on increasingly scarce resources. Where aid once covered a broad spectrum of legal areas – family, immigration, benefits, housing, education, employment, and more – LASPO took whole swathes of civil and criminal law out of the scope of legal aid.

The Act also removed early-stage legal advice, meaning clients are now seeking advice at points of crises instead of when they initially develop.

Fire-fighting, practitioners now say, rather than fire prevention.

The Act has largely been considered a cost-over-quality exercise brought in by the coalition government that aimed to reduce spending by £350 million a year. But amongst the rubble now lies a system failing to support whole areas of the country in desperate need of advice.

A point exemplified by government figures that show that half of all law centres and non-profit legal advice centres in England and Wales have closed since 2014, creating what many have called legal aid deserts.

Interactive data map from The Law Society showing showing a dearth of free housing related legal advice.

The Law Society also found that almost 40% of the population of England and Wales do not have a housing legal aid provider in their local area, a figure that has grown by around 2% since 2019.

Interactive data map from The Law Society showing showing a dearth of free legal advice relating to welfare.

The Law Society also found that 7% of the population do not have access to a welfare legal aid provider.

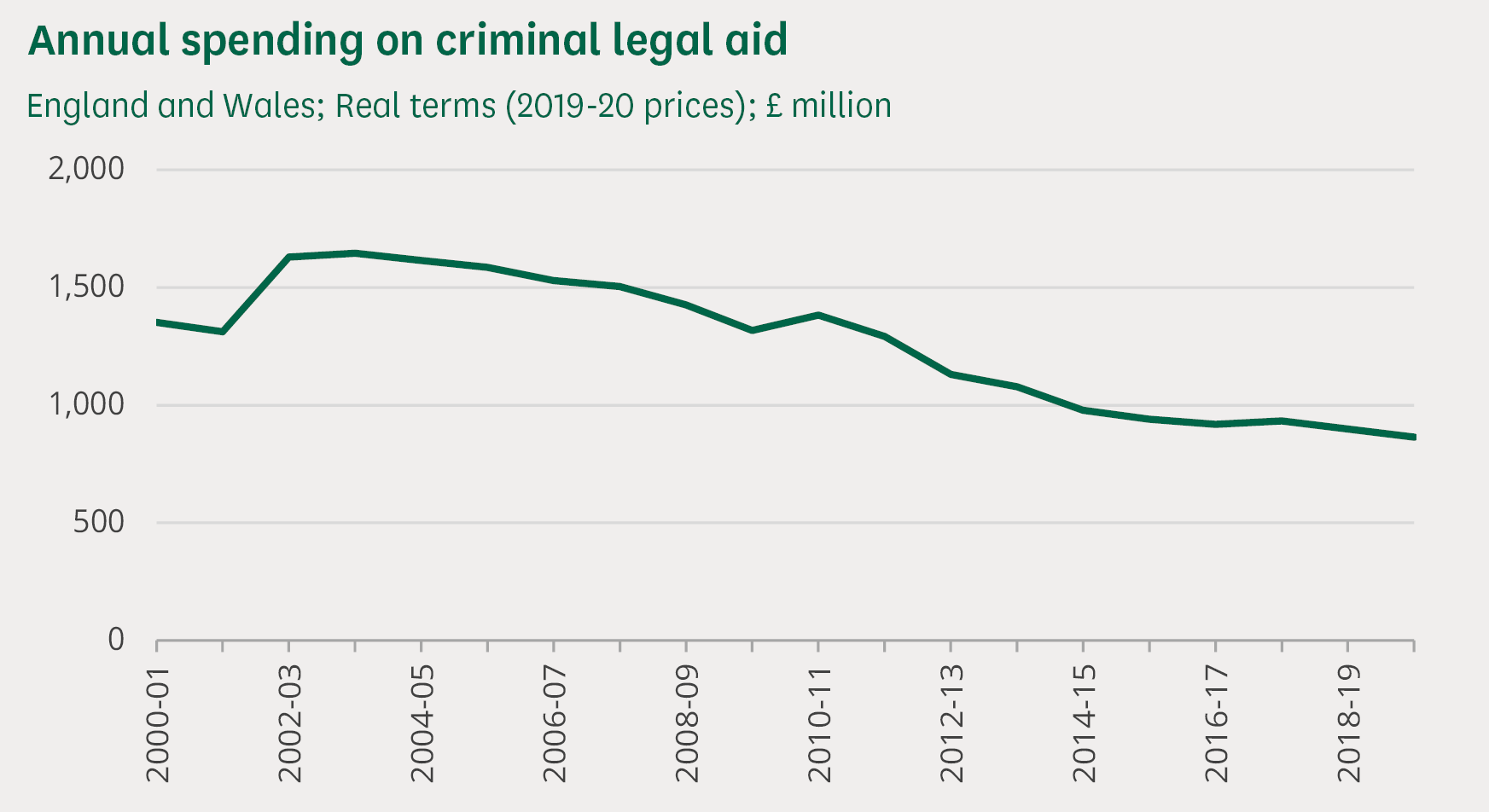

Source: MoJ, Legal aid statistics, January to March 2021, table 1.1; HM Treasury, GDP deflators at market prices, and money GDP March 2021 (Quarterly National Accounts)

Source: MoJ, Legal aid statistics, January to March 2021, table 1.1; HM Treasury, GDP deflators at market prices, and money GDP March 2021 (Quarterly National Accounts)

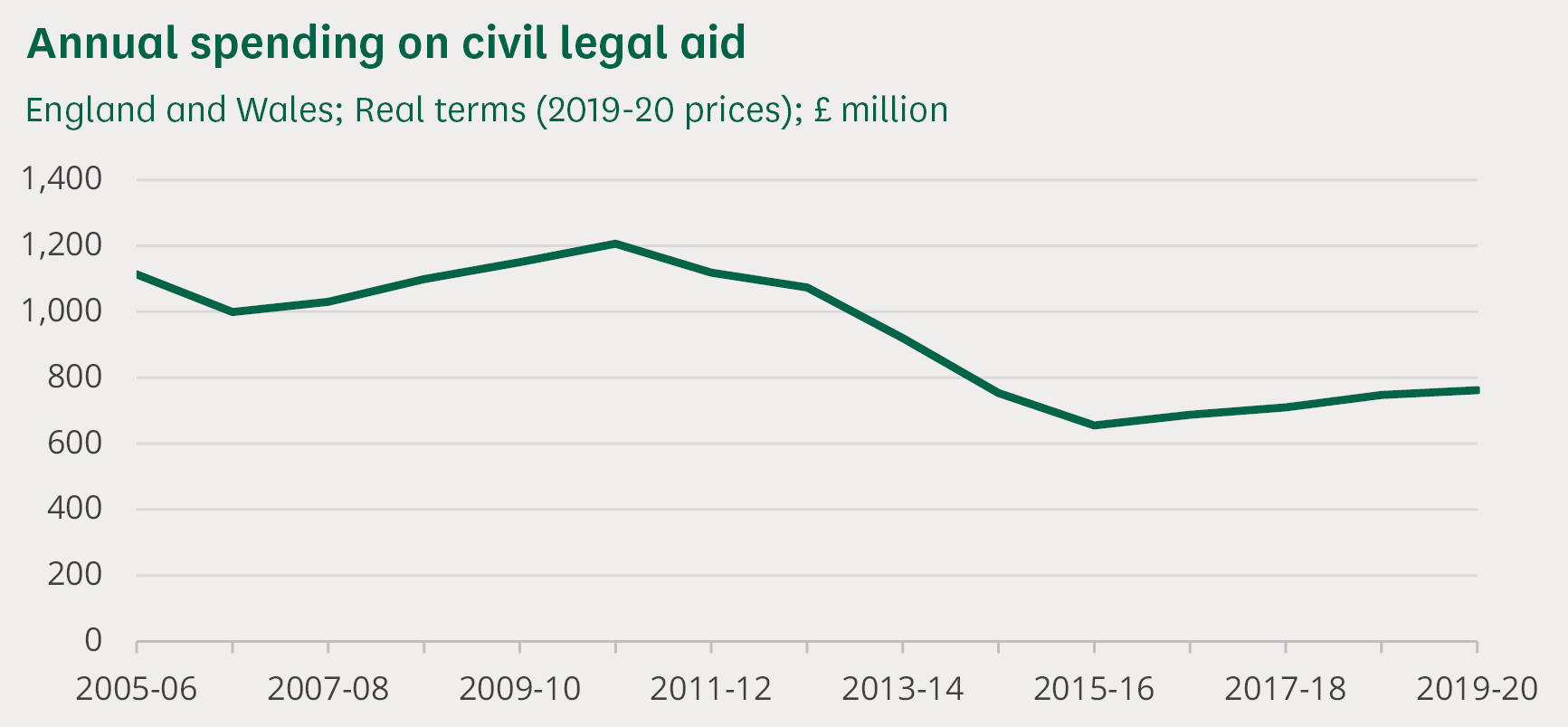

Source: MoJ, Legal aid statistics: Jan-Mar 2021: table 1.0; HM Treasury, GDP deflators at market prices, and money GDP March 2021 (Quarterly National Accounts)

Source: MoJ, Legal aid statistics: Jan-Mar 2021: table 1.0; HM Treasury, GDP deflators at market prices, and money GDP March 2021 (Quarterly National Accounts)

A system ill-equipped to meet current demand was pushed even closer to the edge by the pandemic and subsequent lockdowns, with disputes over employment rights, housing, and benefits coming into stark focus.

Issues around safe working conditions, redundancies, and disagreements around furlough were just some of the pandemic-related employment issues that legal aid does not cover.

Lance Baynham, employment and discrimination caseworker at South West London Law Centres, speaks to the issues this caused.

Baynham said: “The vast majority of employment rights are virtually meaningless unless you can afford to pay for advice. Access to justice is absolutely being denied.”

According to Baynham, the inability to provide advice for these matters has costly implications.

He said: “Cutting most of employment law out of scope saved huge amounts of money in one sense but it adds a huge amount of cost elsewhere.

“It creates far more unnecessary litigation as people can’t get the early-stage advice and therefore they go unrepresented. This all adds to the delays and cost as people understandably don’t understand the complex employment tribunal system.”

Our @SWLLawCentres run one of the UK's largest legal advice clinic services, with around 400 pro bono lawyers giving around £2m of free legal advice each year. The clinics enable people to seek legal redress and empower people through knowledge. #WeDoProBono #ProBonoWeek pic.twitter.com/Ck513dgsq4

— Law Centres Network (@LawCentres) November 1, 2021

A Justice Select Committee report on the future of legal aid was released during the summer and laid bare many of the problems undermining the sector.

One issue raised concerned the inadequate payment for publicly funded work, with many commentators suggesting that the limited career paths and unsustainable remuneration for junior practitioners means that the publicly funded work is no longer an attractive career proposition.

So much so that Nigel Lithman QC, former head of the Criminal Bar Association (CBA), recently suggested that he could not see “any alternative” to industrial action over the dispute around legal aid fees.

Figures from the CBA also show that 22% of junior criminal barristers have left since 2016.

The report clearly argued that without significant investment, the current legal aid framework will no longer function.

Baynham said: “Without reform, the problems highlighted recently will only continue to deteriorate. There are some serious issues facing a sector that requires significant and overhauling reform.”

Jeinsen Lam is a team leader and housing solicitor at South West London Law Centres.

Lam said: “The pandemic has highlighted the real structural problems that exist within the benefit system and housing policy which condemns many clients to live in poor housing conditions without enough money to meet their basic needs.

“In our experience there is a real problem where people are forced to accept insecure work and the benefit system does not provide a sufficient safety net to stop households lapsing into crisis”

Despite the pandemic not creating these problems, Lam argues that they have only intensified across the last 18 months.

He also adds that the recent report on legal aid strikes an all too familiar tone.

"Our vision is for a country where legal capability is spread throughout our society ..It is a country where no-one, no community, and no section of society is denied justice." How many times have we heard similar words from ministers? It means nothing. #deedsnotwords https://t.co/ir7oKYH8kK

— Jeinsen Lam (@JeinsenLam) November 1, 2021

Lam said: “I want to see courage from politicians to address the access to justice crisis within the country and the factors which drive people into poverty and homelessness.

“Cutting £350million out of the legal aid budget off the back of years of underfunding has meant that many people struggle to get the help they deserve when they face everyday problems such as discrimination at work, poor housing conditions or homelessness and evictions.

"The state of the legal aid sector is such that radical measures are now required to ensure that access to justice is more than illusionary for the majority within the country.”

Looking ahead, Lam calls for serious and deliberate investment for this chronically underfunded sector.

He said: “Poverty and homelessness are not inevitable and what the pandemic has shown is that where there is a political will to deal with a particular issue then the financial challenges that often follow are not insurmountable.

“I would be very happy if society did not need social welfare lawyers,” Lam concluded. “However with homelessness, child poverty and inequality rising, the need for specialist holistic legal advice has never been clearer.”

SWLLC was Highly Commended in the Excellence in Access to Justice Award in the Law Society Awards 2021.