“Please, let me go see my family”

Eighteen months into the pandemic and half a year since travel restrictions were first imposed, migrants with family abroad continue to struggle to meet loved ones

Travel restrictions have been at the centre of the debate since March 2020, but the conversation often ignores a group of people with no right to vote: migrants.

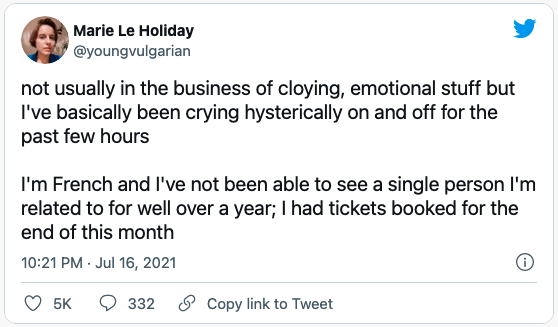

For French freelance journalist Marie Le Conte, the word that comes to mind to describe her own mental state is “knackered”.

It is not an unfamiliar feeling, but unlike the vast majority of people in the UK, she was not born in this country and most of her relatives reside across at least one national border.

“The past 18 months sucked big time,” she summarised.

"Staycations" have surged by up to 40% in some areas of the country this year as foreign travel stalled during the pandemic.

Under current restrictions, international travel is governed by a traffic light system, with the most dangerous countries categorised as red and requiring arrivals to quarantine in a hotel.

Travel from amber-list countries, the most popular group, is allowed but not encouraged, and requires an expensive series of tests upon arrival in the UK.

The added costs that have deterred holidaymakers from going abroad are frustrating migrants' hopes to visit their loved ones and reunite after months apart.

Marie Le Conte, celebrating on her Instagram page the announcement that double vaccinated people wouldn't be required to quarantine after returning from France in early August.

Migration and international travel

Like most people, Le Conte recalls the last 18 months in chapters marked by restrictions on movement.

“I don’t really remember the first lockdown.

"I tried to stay busy because I don't like doing nothing, so I did lots of weird sports, I learned how to draw and paint; I bought a tattoo kit, I tattooed myself; I shaved my head…” she listed with a sardonic laugh.

“Yeah, I was not well. All of that was in the first three weeks, by the way.”

She described the summer breezing by, and then we compared experiences of resignation (hers) and despair (mine) during the Autumn and Winter lockdowns.

"I tried to stay busy because I don't like doing nothing, so I did lots of weird sports, I learned how to draw and paint; I bought a tattoo kit, I tattooed myself; I shaved my head...”

When spring arrived, vaccinations made everything feel celebratory, as if the pandemic was nearing completion (Le Conte was eligible for the shots early on).

“I think that’s partly where that frustration came from: I’m double vaccinated, I am safe.

“Please, let me go see my family.”

Le Conte is a self-described "extremely social person" with ADHD, so she never thought she could cope with ten days of self-isolation in her one-bedroom basement flat.

Her finances having taken a toll over the past year, spending an extra hundred pounds to “test to release” on day five of isolation was out of the question.

“Even my family, when I told them ‘I can't do this’, they were like, ‘Oh, we know that - We know you, obviously you can’t self-isolate for 10 days’," she recalled.

She added: “It was like, thank you, you do understand.”

Le Conte hoped to travel in early July – had purchased her tickets, announced her travels to her relatives – when without prior notice, the UK government established the so-called “amber plus” travel list for France.

The hybrid invention restricted travel from certain amber countries, and was described by members of the French government as “incomprehensible”.

The political journalist could not find any explanation for the sudden move.

She said: “I think they were really scared about the Beta variant, but that to an extent doesn’t make sense, because France has very little Beta variant.

“I still don’t understand, especially to then reopen three weeks later – so, okay, you ruined the holiday plans and the lives of people for three weeks?”

What is often forgotten is that families abroad are equally invested in these policy decisions: when France was moved back to the regular amber list, allowing travel once again, the journalist was first contacted by her grandmother.

As I write this, I gather from Le Conte’s Twitter feed that she has successfully made it to France, after a year unable to cross the Channel.

There is more to travel than holidays

Prime Minister Boris Johnson first announced the imposition of testing for all international arrivals in January 2021.

Following many conversations with immigrants in the UK, the general sense behind travel restrictions is one of incomprehension at both action and inaction.

According to the latest government-issued data, reflecting pre-pandemic values, there are 6.2 million foreigners in the UK, 9% of the total population.

This figure accounts for people living in the UK who were born in another country, but does not reflect the experiences of first- and second-generation immigrants, who may still hold strong ties to other countries.

Out of the ten most common countries of nationality, which account for over 3.1 million people residing in the UK, only Romania is on the green travel list, with the least level of restrictions (travel to Ireland, as part of the Common Travel Area, is not affected by international travel restrictions).

Experiences of migration are as diverse as there are migrants in the UK.

Most people come with the expectation to make a life, or at least a living, and the deepest hope that the cost of doing so won’t be too high.

Lockdowns and restrictions weigh differently on different people.

A timeline of the lifting of Covid-19 restrictions, highlighting the return of international travel on 17 May 2021.

A timeline of the lifting of Covid-19 restrictions, highlighting the return of international travel on 17 May 2021.

More than eighteen months into this unprecedented experiment, there is no sign of stability coming.

Since the Prime Minister’s first announcement of travel restrictions, the rules have changed every three weeks, sometimes so unexpectedly it has caught newlyweds on their way to their honeymoon, only to turn back straight away.

The colour-coded travel list is usually reassessed in that time frame but sudden changes based on evidence can come at any time, as happened with France.

For those visiting a country that moves from amber to red, arriving in England after the established deadline incurs an extra fee of £2,500 to pay for hotel quarantine - a bill not many want to risk.

Traveling back from an amber-coded country requires several tests but, since 19 July, those who have been double-vaccinated don't have to self-isolate.

Caring from London to Spain

At this point I should make clear that I understand and support measures to lessen the public health impact of the pandemic.

The purpose of writing this is not to oppose these measures, but to reflect on the heavy toll brought by the uncertainty they create.

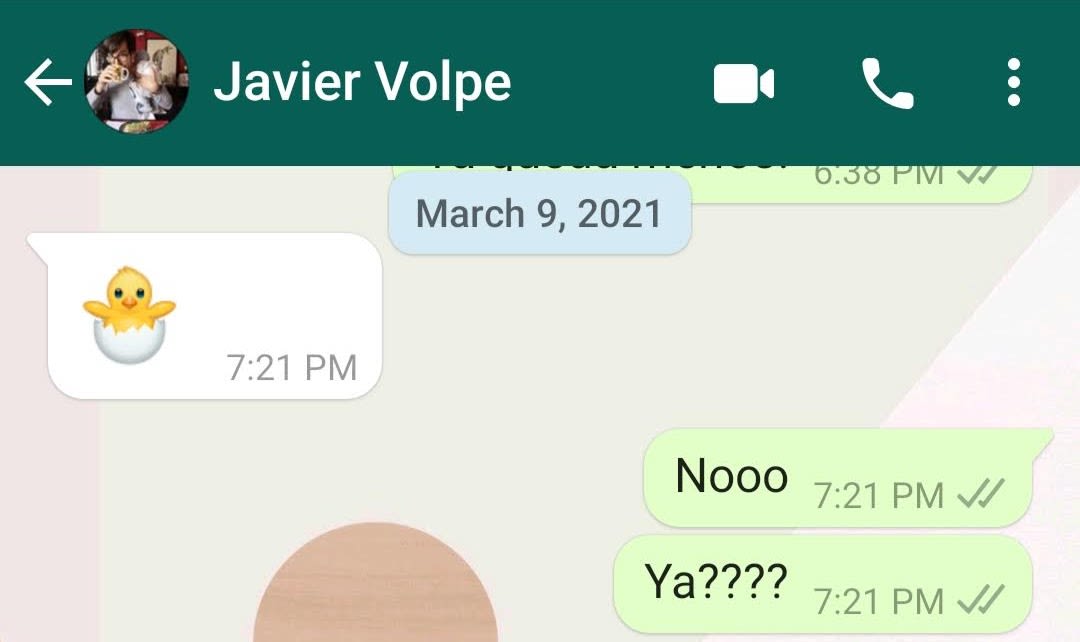

For me, the weight feels extremely personal and particularly heavy: my sister's daughter was born five months ago and I have only seen her through my phone screen.

It will be at least another month before I get to meet her, if the rules for travel to Spain don't change.

After a year of online communications, it felt appropriate to find out she was born through a hatched egg emoji.

After a year of online communications, it felt appropriate to find out she was born through a hatched egg emoji.

The author and her sister, Isabel Santiváñez, at ten weeks pregnant. Credit: Javier Volpe.

The author and her sister, Isabel Santiváñez, at ten weeks pregnant. Credit: Javier Volpe.

The communication over the first minutes of my niece's life was a reflection of what was to come, as we adapted (even more) to this new way of connecting with one another, and a baby.

My niece's and my relationship has evolved over WhatsApp, where I coo at her and hope for a gargle, and videos sent by my sister, where she gets her to smile to the camera and make noises.

We try and build memories from a distance.

As a baby, Marta is all giggles and tickles. She is curious and inquisitive, she really likes looking beyond her pram and reaching for the trees in the park. She keeps her parents up at night and rolls around like a champ.

I have so much pride for that little human, it feels incomprehensible – yet I love my sister fiercely, how would I not adore her daughter?

Marta Volpe Santiváñez, playing with one of her toys, as seen in the author's mobile phone. Credit: Isabel Santiváñez.

Marta Volpe Santiváñez, playing with one of her toys, as seen in the author's mobile phone. Credit: Isabel Santiváñez.

The author's niece laughs as her mother plays with her and calls her out: "Hey, you"

The invisibility of many people's experiences in the pandemic has been demoralising and often hurtful.

Migrants work for the NHS in frontline positions, stock supermarket shelves and care for the elderly, and sometimes we write articles, too.

As for me, I am excited for the future, and some days I am even a little hopeful, but my days and plans are surrounded by uncertainty, as is the case for anyone in a similar situation.

Which is all to say, Marie, I too am knackered.

(But listen to that laughter).