London’s boaters feel the strain as hundreds leave rental markets for the canals

Faced by an acute housing crisis in London, many would-be renters have turned to canal boats to live in the capital without paying extortionate rents.

The influx of newbie boaters has increased pressure on services, contributing to the Canal and River Trust's (CRT) decision to announce new fee hikes and stoking some tension within the established community.

In reaction to fees hikes, in late November members of the boating community conducted a protest at the CRT's headquarters in Central Birmingham.

James Lowe, a boater himself and narrowboat safety inspector, said: “The way of life for the liveaboard is in question.”

However some of the issues facing the CRT and the dwellers who live on the network run deeper than simple fee increases.

A sign for eco-mooring in Islington topped by a poster calling for a national protest against license fee increases. Eco-moorings have electric charging points to stop boatings from having to run engines in urban areas.

A sign for eco-mooring in Islington topped by a poster calling for a national protest against license fee increases. Eco-moorings have electric charging points to stop boatings from having to run engines in urban areas.

Boating in London

Canal boats can be divided into those with permanent moorings, and continuous cruisers, who must move every two weeks.

To live on the network, which encompasses 2,000 miles of canals and rivers across Britain, boaters pay the CRT a license fee. With a license fee boaters get access to some facilities, such as water and sewage pump-out points, rubbish and recycling bins, and dry docks, though continuous cruisers have have reported shrinking numbers of amenities available.

Beyond that, owners have to insure their boats and have it inspected through the Boat Safety Scheme run by the CRT every four years (similar to an MOT).

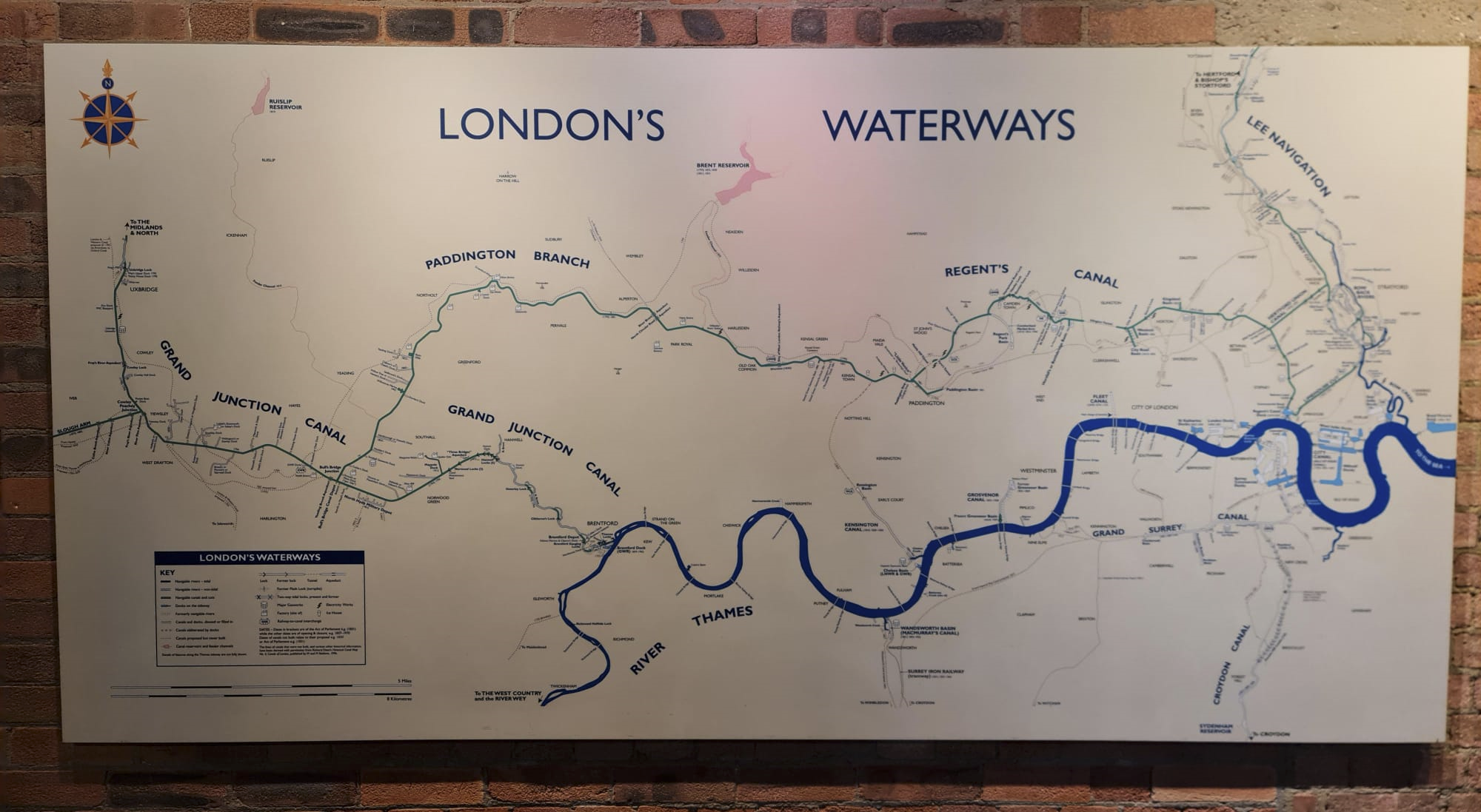

London's Canal Network, encompassing the Regent's Canal, Grand Junction Canal, Limehouse Cut, and Lee Navigation. From The London Canal Museum

London's Canal Network, encompassing the Regent's Canal, Grand Junction Canal, Limehouse Cut, and Lee Navigation. From The London Canal Museum

The organisation in charge of the waterways is the Canal and River Trust (CRT), formerly the state-owned British Waterways.

Britain nationalised the waterways in 1947, as river trade began its long decline from the heydeys of the 1870s when over 40,000 people worked on Britain's canals, shipping coal, timber, ice, cocoa and more across the country from the ends of the empire.

In 2012, guardianship was transferred to the CRT, a new charitable organisation that maintains the network in England and Wales, funded by the fees, government grants, donations, and a burgeoning property portfolio.

Whilst nothing compared to their previous heights, the canals are becoming more busy as the number of continuous cruisers in London has skyrocketed more than 400% in a decade.

Numbers have gone from less than 500 continuous crusiers on the water in 2010 to more than 2000 a decade later, whilst permanent moorings are relatively more stable.

Nationally, permanent moorings are in the majority, encompassing almost three-quarters of boats, whereas in London, the split is nearer 50:50, with continous crusiers being the slightly larger group.

Another newer group in London are tourists, using AirBnB in the summer to rent out boats that cause consternation amongst continuous cruisers and permanent moorings alike.

Inexperienced and generous with the throttle, these users can often cause damage to the locks, and other boaters. Whilst it is against the law, requiring an additional license and insurance, the CRT says that hosts are clever, obfuscating their photos to conceal which boats are being illegally piloted.

Life on the Move

Ramin Saifollahi Fakhr, 61, has no plans to return to land.

He said: “To do that would be admitting defeat.”

Fakhr moved onto the water after struggling to find housing that would accomodate his two dogs, and has now lived on his boat for over a decade with his partner, and teenage daughter who has since moved out.

Over the years, Fakhr has become almost self sufficient, installing solar panels on the roof for energy, scavenging for wood for warmth, making jewelry and leatherwork, and working as a handyman.

He lives on the boat with his partner Loisa, who works in social care in a school, and new puppy, Tigzy, moving as they please around London.

His cruiser, a converted lifeboat called AK50, named after his children, frees him from being trapped in a long mortgage and compelled to work.

However, it has not been without difficulty.

He has had residents unhappy with his presence try to smash his solar panels. Attempted burglaries are common, especially around Christmas time, when most boaters leave their boats moored to go visit their families.

When he first moved onto the canals with a 9-year old daughter, having to move every two weeks made schooling difficult. He would move up and down the Metropolitan line from Watford to Little Venice and back again to make sure she could get to class on time.

Access to public services can be difficult for continuous cruisers, who do not have a permanent address.

Despite a legal requirement for them to be served, many struggle to access proper medical and dental services; Fakhr has not been to the dentist in over a decade.

Daisy, another new, young boater, has also struggled to access medical services, continuing to stay registered with a GP where her parents live.

Often public services are not used to handling such edge-cases, leaving boaters without care.

For example, the fuel support provided during the winter of 2022/2023 to everyone in England was not available to continuous cruisers, who only received it this summer after an extended campaign from the CRT.

A Resilient Community

Though there are difficulties, the continuous cruiser community are resilient by necessity.

Life on the canals requires a level of physical fitness to operate the locks that separate the canals, and a mental acuity to take care of needs for water, electricity and other dangers.

Daisy said: “It's a demanding lifestyle. You have to be constantly conscientious of what you're doing.”

A boating community exists on the water, but given all their movements, much of it takes place online.

Boaters on groups such as "London Boaters" swap advice, notify each other of desirable moorings, recommending engine parts and quick fixes, warning against dodgy surveyors and offering assistance when someone is adrift or broken down.

Sylvester, 21, a London-based student and artist who recently purchased a boat “Foxtail” in order to live in the capital, was heavily reliant on the help of such groups.

Due to the variable nature of his work and lacking a guarantor, Sylvester was unable to rent, using all his savings to buy his narrow boat.

He said: “I think if the community wasn’t so helpful I wouldn’t have gone ahead and done this.”

Gender also plays a role in the boating experience. Though decreasing, many towpaths in London are unlit and can feel unsafe to travel at night for a solitary female boater.

James Lowe, who runs Tortuga Marina Services and conducts inspections for the Boat Safety Scheme, said some surveyors take advantage of female boaters, billing for unnecessary work and being overly friendly.

Daisy said: “The London ‘Boat Women’ page is significantly more helpful and willing to educate those that don't understand. Whereas if you put a question in London Boaters, you often get responses that sort of suggest that if you don't understand then you shouldn't be doing it sort of thing.”

The Old and The New

Though more and more people choose have abandoned land to avoid high rents, for some on the water the costs have risen to the point they want the opposite.

Despite a decade on the water and running a boating company, Lowe feels that the CRT is sidelining continuous cruisers in favour of permanent moorings, which pay a higher rent-like fee for mooring.

Lowe said: "I'm thinking of selling up and going on to land."

He plans to transition back to renting as boating no longer provides the same discount it once did.

The annual license fee ranges between £600 and £1,500, depending on the dimensions of the boat, and whether you want access to just rivers, or canals too. According to the CRT, it averages at about £850.

For comparison, the average monthly rent for a two-bedroom property in London is £1,500, though boats are mostly owned outright and cost easily north of £35,000.

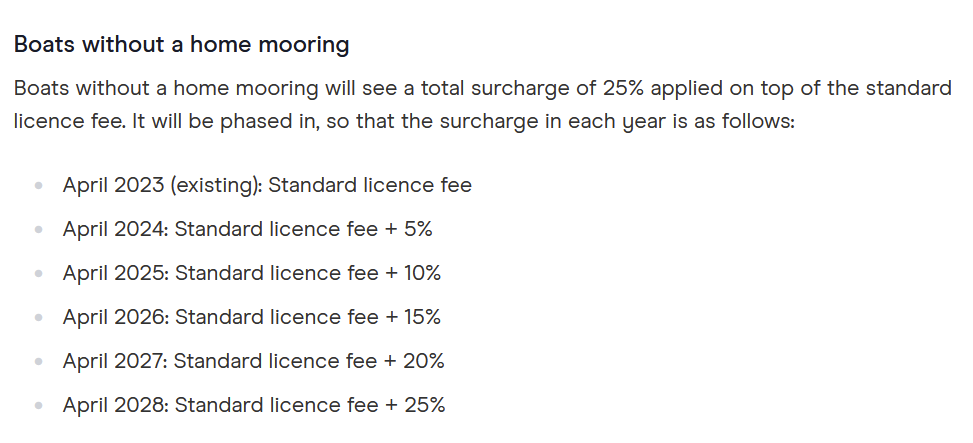

The CRT's new license fee structure has a "standard" inflation-linked fee for boats with a permanent mooring, with extra added on top for continuous cruisers.

CRT license fees for continuous cruisers over the next five years

CRT license fees for continuous cruisers over the next five years

Using the network mainly in the summer months some refer to the permanent moorers as “shiny boaters” or “mushroom polishers”, for the well-buffed brass vents often found on top of their boats.

Matthew Symonds, strategy and engagement manager at the CRT, said they are not trying to favour any group but that the increased fees for continuous cruisers are reflective of their higher usage of the network and facilities.

Increased continuous cruisers, 90% of who are liveaboards, put more pressure on the locks, water and pumpout facilities, and providing more services requires battling often restrictive building regulations and limited canal-side space in an ever more confined London.

Licenses only account for around 10% of the CRT's annual revenue, with government funding accounting for less than 25% and dropping each year. The rest comes from commercial activity, rents, the national lottery and other philanthropic donations.

Despite increased income in 2022/2023, the non-profit is facing a funding squeeze, with the government’s new funding grant agreed this summer actually cutting support by over £300 million in real terms over the next decade.

In response, the CRT has launched the “Keep Canals Alive” campaign in July to sustainably fund the waterways, which requires maintaing and repairing thousands of locks, reservoirs and embankments.

Reservoirs flooding can cause millions of pounds of damage, evacuations and risk to life, as they have in Calder Valley in Yorkshire multiple times over the past decade.

Symonds said: "We've been negotiating the renewal of our grant for a few years, and they've published their findings, which, in a nutshell says, you're good value for money, you're delivering a lot of good stuff and it's been a real success. But then at the same time, they said we're going to reduce by 5%.

"When the grant was established, we don't think it fairly reflected both the value of the canals in terms of public use and benefits that people enjoy from them. But also we look after a lot of critical infrastructure, but if it goes wrong, you have a big problem."

Symonds said the whilst the CRT is not mandated to provide affordable moorings, they do have welfare officers available that provide guidance and support to those boaters in need. Charities like Julian House also provide support and Lowe himself provides a subsidised rate for liveaboards.

Watch the below video interviewing Matthew Symonds from the Canal and River Trust talking about the challenges in sharing London's waterways. The canal shown in the video is Regent's Canal from Bethnal Green to Union Wharf near Angel.

Some are more sympathetic to CRT’s juggling act of keeping all the various parties happy whilst maintaining the network.

Will, 37, who bought his mid-60’s house boat as an accessible first rung on the property ladder thinks the license fee is actually well priced.

Will said: “Money talks. In the future coming down the line in London and the canals as they're currently being operated, you're going to see a lot more bigger, snazzier boats.”

But there is hope that there will still be space for everyone to enjoy London’s waterways.

Sylvester said: “It is a project, it’s a life long project, and its a completely different way of living but it feels a lot more fulfilling.”

All photos and videos taken by Daniel Orchard