London's forgotten flood

50 years since the Hampstead Storm

Physically restrained from swimming down the road, eyes frantically searching the horizon, she felt like her heart would explode out of her chest.

This was the reality for Jenny Weller, a distraught mother who had one question running rampant through her mind, as the world outside her house turned into a lake:

"Where are my children?"

What was to follow would be a day of fear, uncertainty, and most of all, water.

A storm was brewing that would leave its mark on her and her children forever.

A "1 in 20,000-year storm" that would become legend in academic circles.

But a storm that would fade from the popular record and pass into relative obscurity.

Yet according to David Smart, Honorary Research Fellow at UCL's Department of Earth Sciences: "The Hampstead Storm is the storm we should not forget."

David Smart of UCL's Department of Earth Sciences highlights the importance of the Hampstead Storm

David Smart of UCL's Department of Earth Sciences highlights the importance of the Hampstead Storm

A summer day, children at play

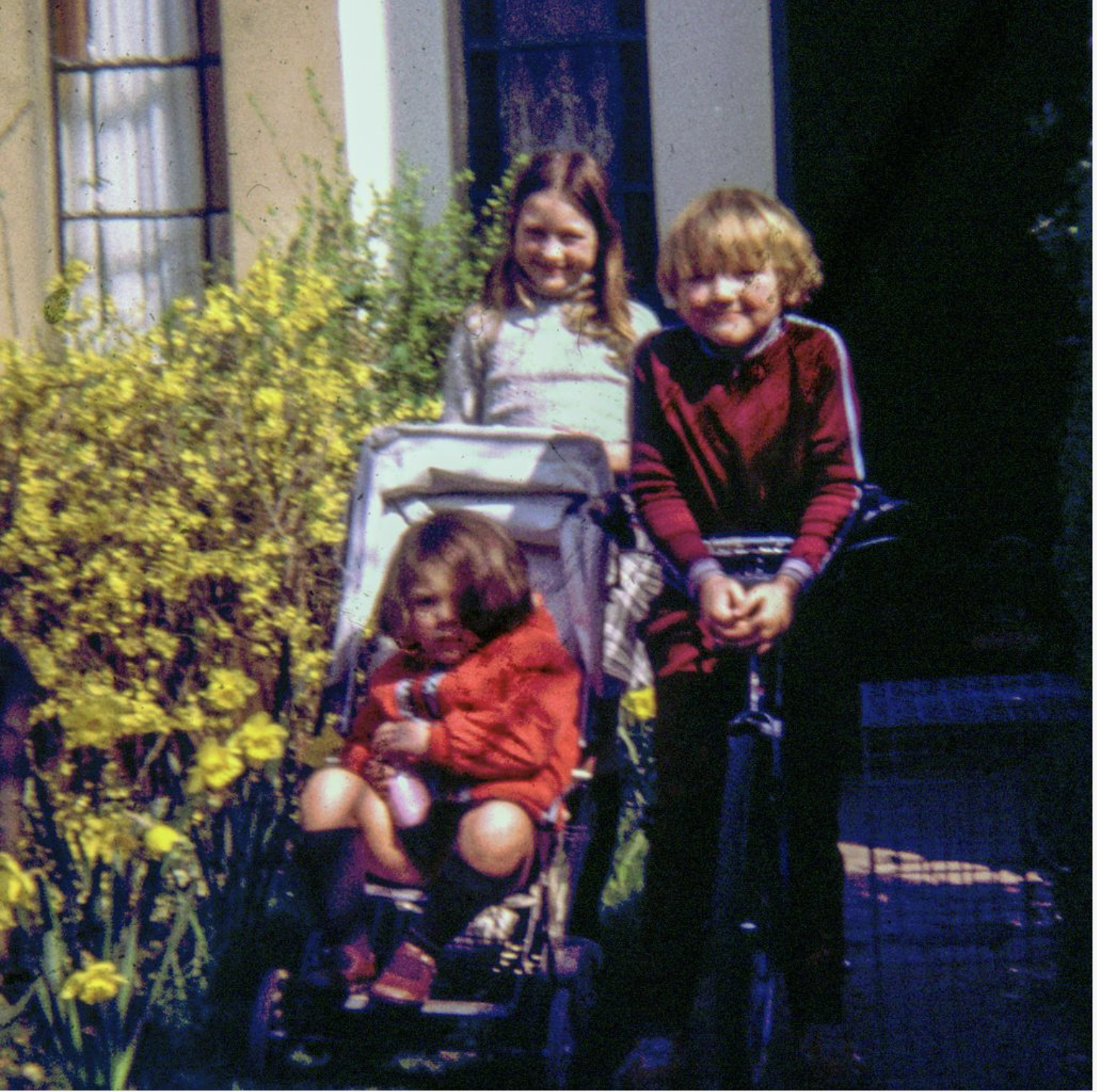

Two hours earlier on Hampstead Heath, a young boy and girl were engaged in their daily summer ritual of splashing around the Lido, the setting sun and the calls of the lifeguards the only things halting their fun.

For now.

John and April Weller, aged eight and ten respectively, Gospel Oak locals and swimming enthusiasts, were always last to leave the pool. It was the challenge they set each other every day of the summer.

This time they failed, however. A group of teenage boys flatly refused to leave the pool, ignoring the appeals of the lifeguards.

Soon, huge chunks of chlorine were tossed into the water, originally intended to clean the pool, but now cleaning stubborn teenagers out as well. Two for the price of one.

Yet the surface was to be broken by more than just errant chemicals.

Rain began to sheet down from the skies at roughly 6 pm, peppering the pool and sending the already wet Wellers running for cover under the portico of the Lido entrance.

The Hampstead Storm had begun.

John and April Weller outside Parliament Hill Fields Lido in 1975| | Image credit: John Weller

John and April Weller outside Parliament Hill Fields Lido in 1975| | Image credit: John Weller

April Weller 1975 | Image credit: John Weller

April Weller 1975 | Image credit: John Weller

John Weller 1975 | Image credit: John Weller

John Weller 1975 | Image credit: John Weller

The storm begins

The science

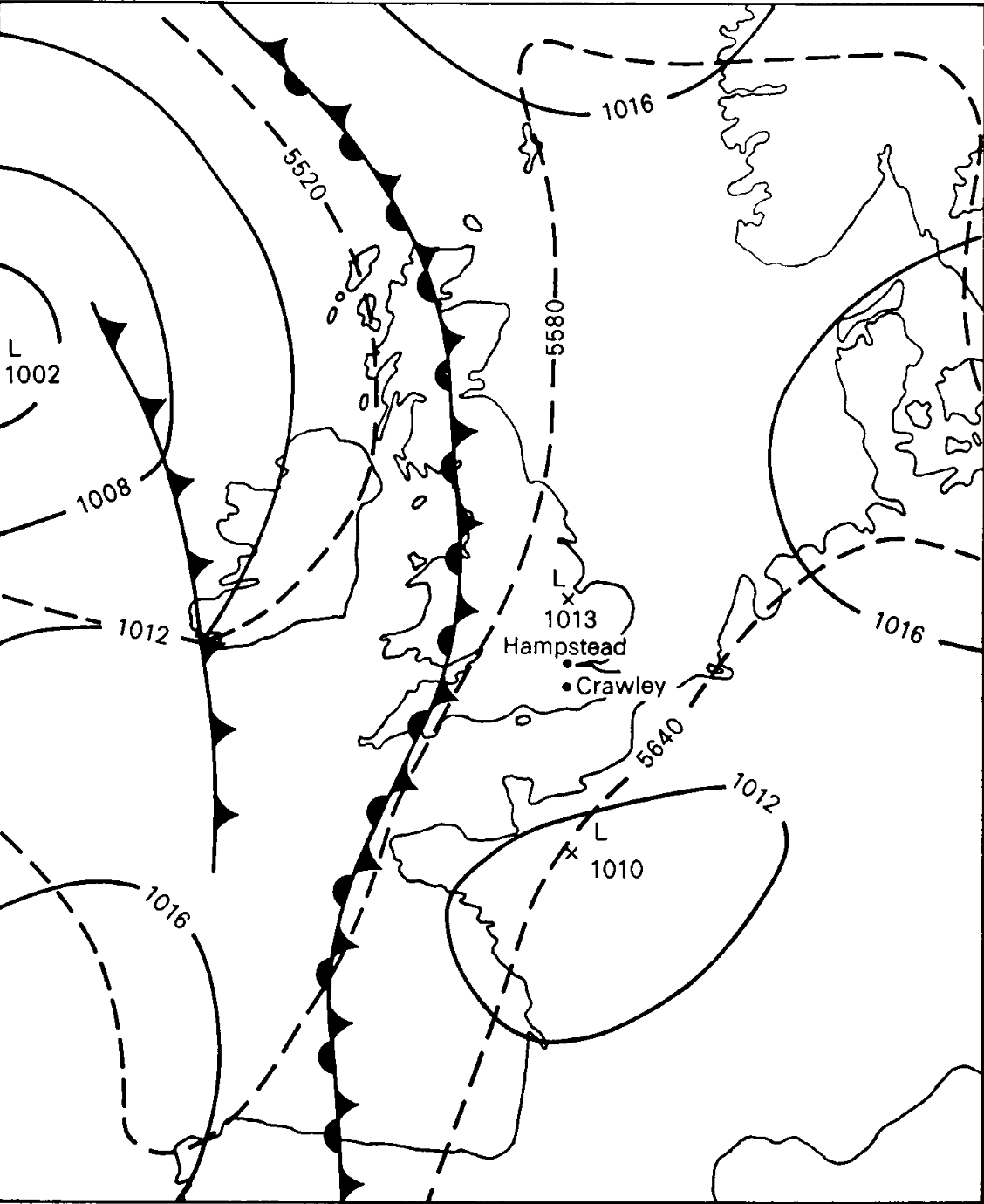

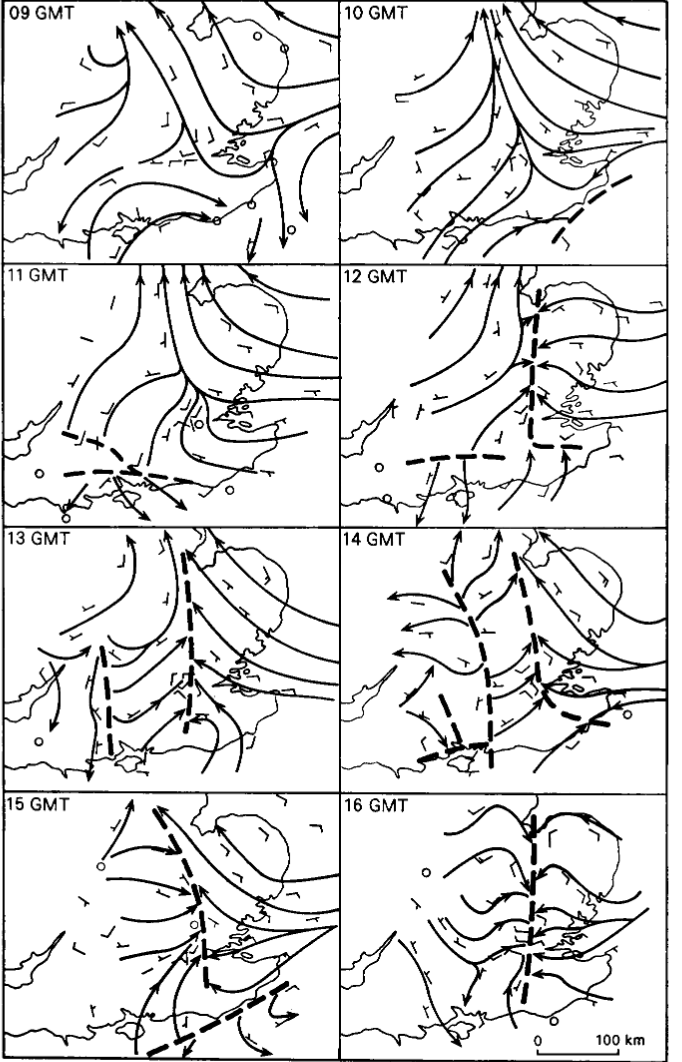

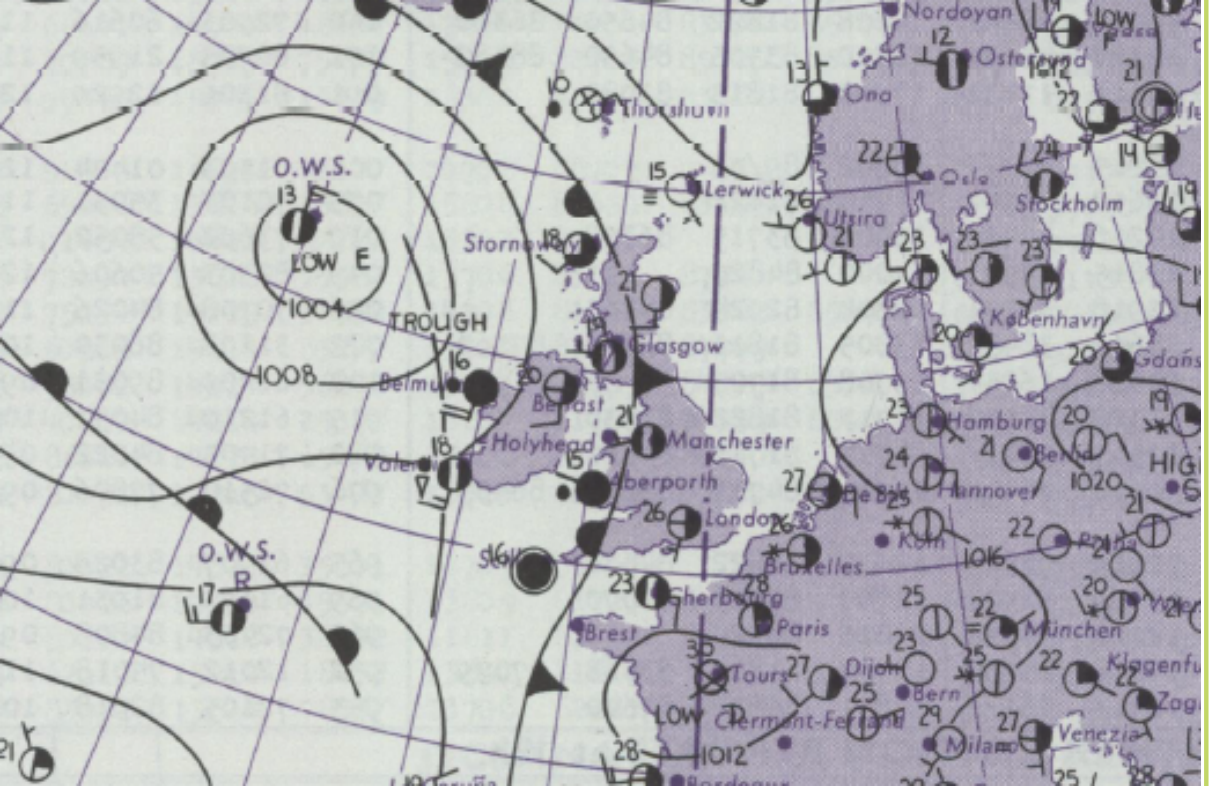

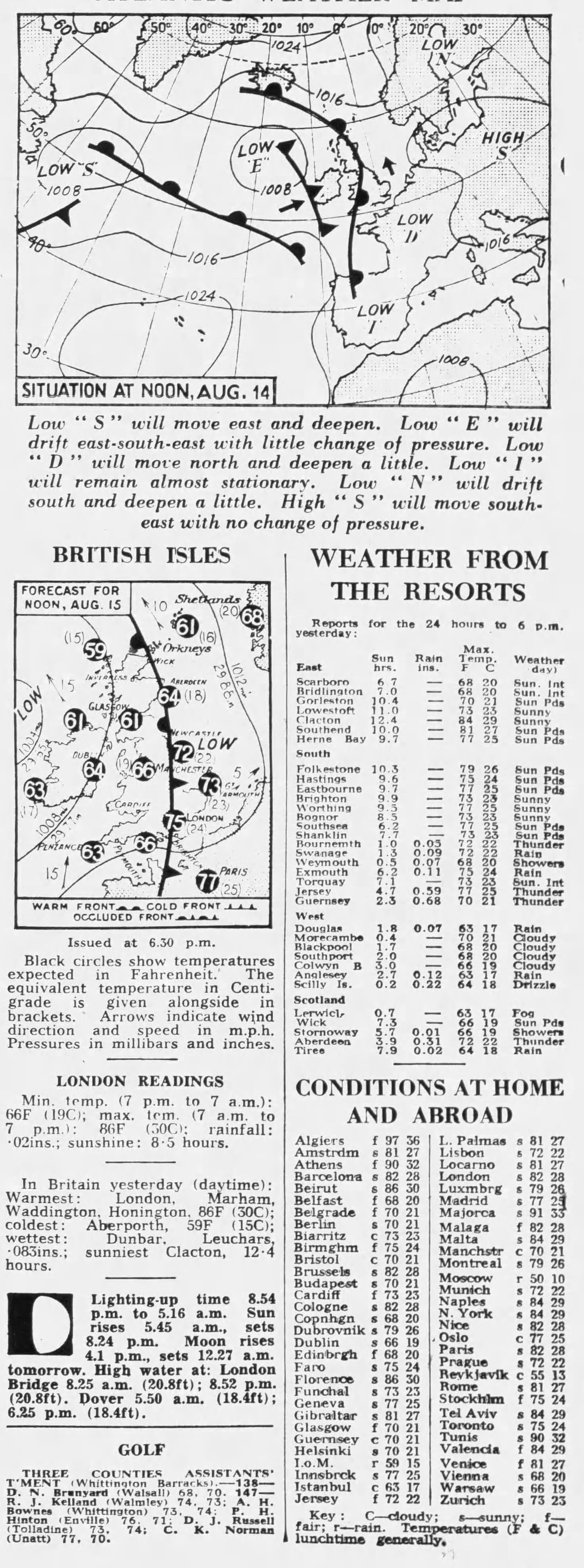

On the afternoon of 14 August 1975, as part of a developing thunderstorm across eastern England, the clouds split apart and unleashed a downpour on North London.

The storm was triggered by a combination of a slow-moving low-pressure system, a frontal system near the United Kingdom, a low-pressure system over France, and warm air from the continent.

It had been an exceptionally hot summer that year, with the UK receiving less than half the usual rainfall. But Northwest London just had to be different.

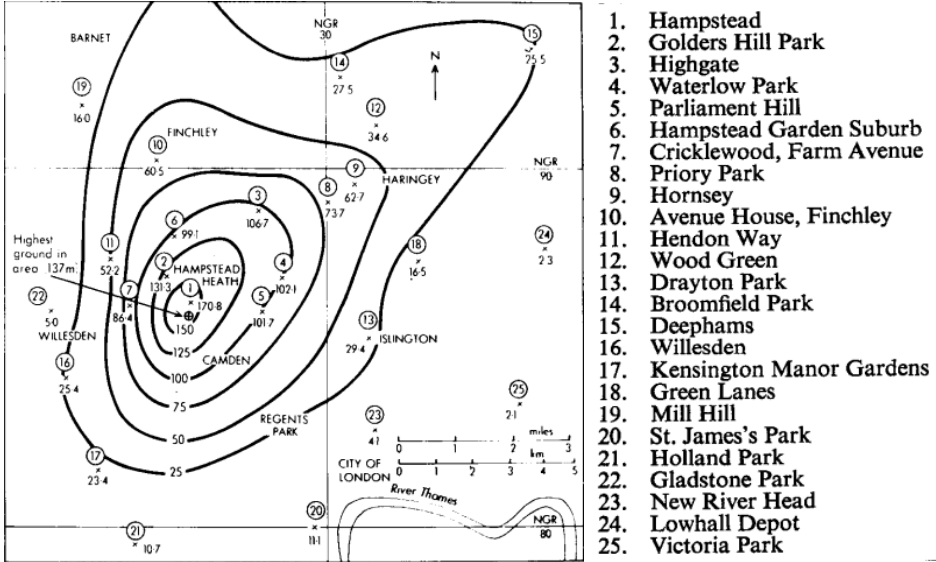

Almost 7 inches (180mm) of rain, around 3 months’ worth, fell in just two hours, the largest daily total recorded in the London area.

However, with water gauges failing due to "damage from debris and being blocked by hail of up to 2cm," according to Smart, real totals were estimated to be in excess of 200mm of rainfall.

Smart explains the build up to the Hampstead Storm

Smart explains the build up to the Hampstead Storm

Joanna Robinson, weather producer at Sky News, added: "The storm was almost stationary.

"It may have been a 'back building' storm system, sometimes referred to as training cells or training thunderstorms. "

Robinson explained that this is where new storm cells can develop in the place of the original storm, with the downdraught from these new storm clouds establishing and sustaining the whole storm system.

The Weller experience

John Weller, now 58 and a travel writer and photographer, said: “I've been to Bangkok, I've seen the monsoon; it’s nothing compared to this. Nothing. I've never seen anything like it.

“We weren’t scared, just excited; it was an incredible thing.

“It was like being in one of the disaster films I used to love;

I kept expecting Steve McQueen to come swimming by.”

John Weller in the Lido, age eight | | Image Credit : John Weller

John Weller in the Lido, age eight | | Image Credit : John Weller

Unable to cope with the downpour, the Hampstead Heath ponds broke their banks, and water poured down the hill towards Gospel Oak.

At the same time, the subterranean Fleet, Tyburn and Brent Rivers belched forth from the earth, adding their hidden waters to the day’s chaos.

This deluge overwhelmed stormwater sewers and flooded gardens and streets, and Smart stated: "It was a very rare and extreme rainfall."

John Hillaby, writing for the New Scientist in September of 1975, said: “The rain and the hailstones barrelled down; they fell in misty sheets with a noise like boiling fat”

Ex-Lido and Hampstead ponds lifeguard, Tony May, 69, then 19, was walking past the Lido down towards Gordon House Road as the heavens opened.

He said: “It was a waterfall, that whole grass and stairs area in front of the Lido, the water was pouring down towards Gordon House Road.”

Tony May (Right) with his two brothers on Hampstead Heath (1974) | Image Credit: Tony May

Tony May (Right) with his two brothers on Hampstead Heath (1974) | Image Credit: Tony May

John would later become friends with the lifeguard, swapping stories of the Hampstead flooding.

Huddling for shelter, John and April, who saw no sign of the rain stopping, decided to make a break for home on Grafton Road, just half a mile away.

But the weather had other ideas.

"It was a very rare and extreme rainfall"

With the water reaching their ankles as they passed Gospel Oak station on Mansfield Road, and water sheeting down off the railway bridge, the pair had a "brilliant" idea.

“Let’s wait inside the station and see what happens!”

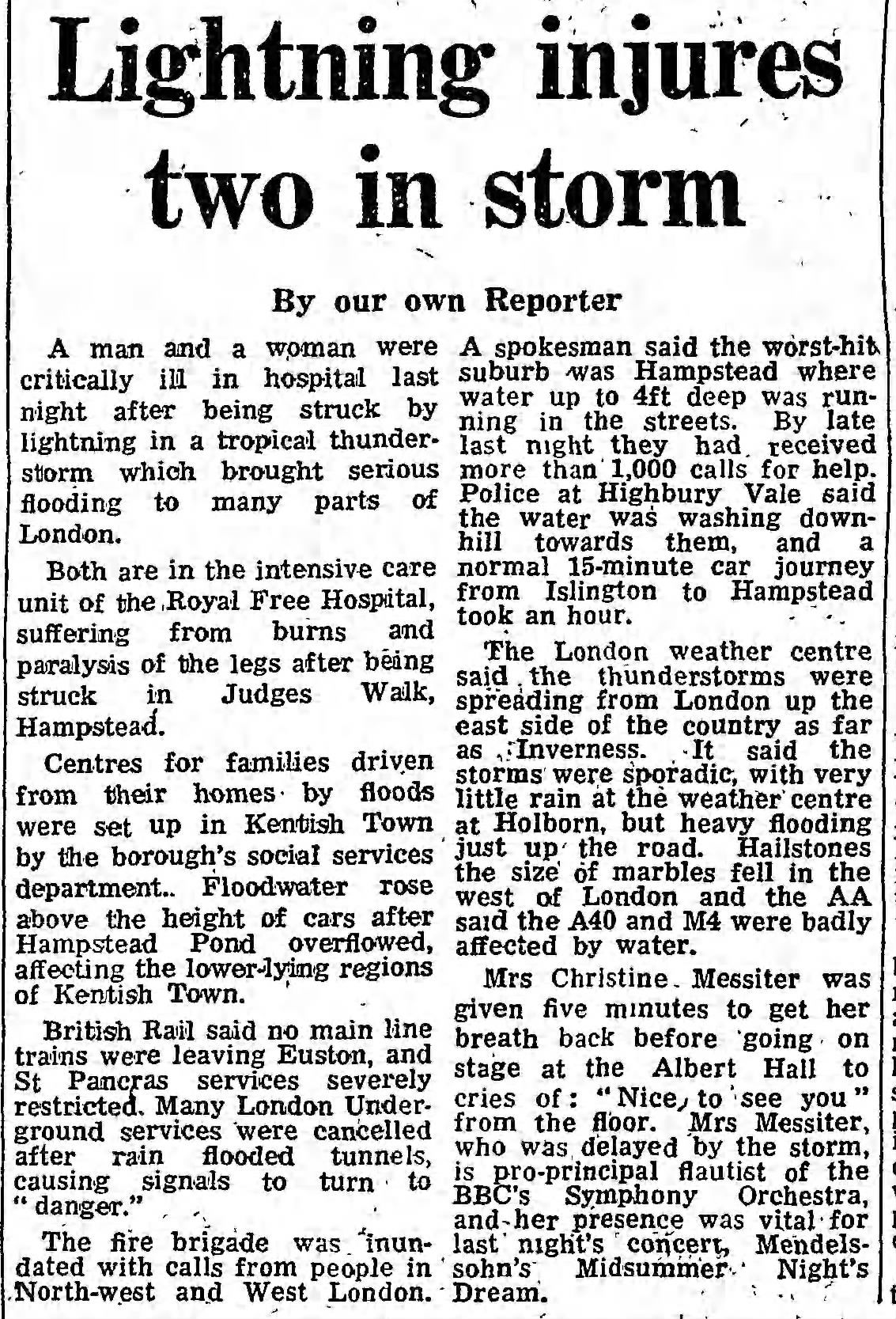

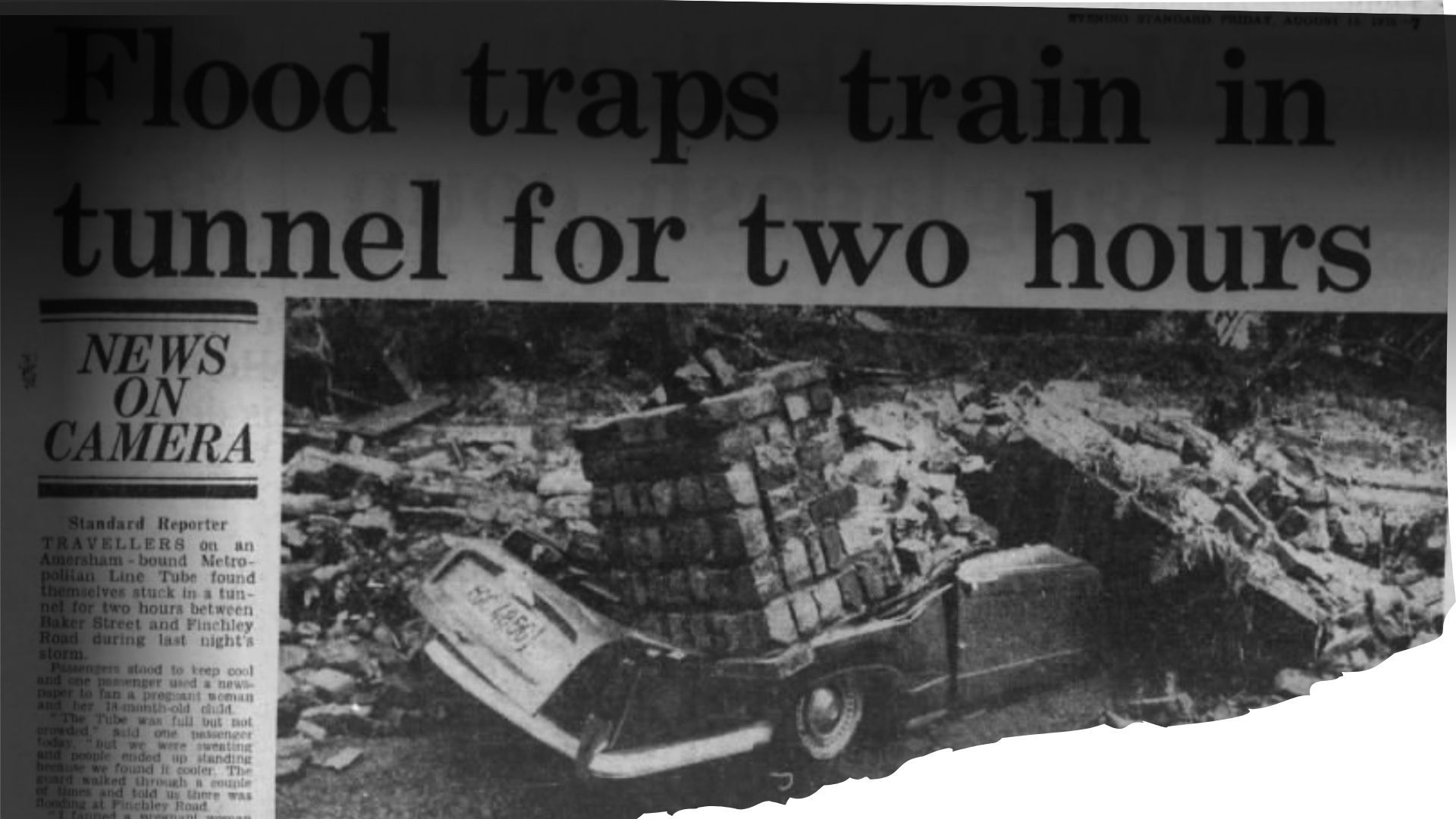

Unbeknownst to them, torrents of water poured into the underground beneath their feet, causing electrical faults and bringing the Bakerloo and Metropolitan lines to a halt.

Services from King's Cross St Pancras were not back in operation until a week later.

“The rain and the hailstones barrelled down; they fell in misty sheets with a noise like boiling fat”

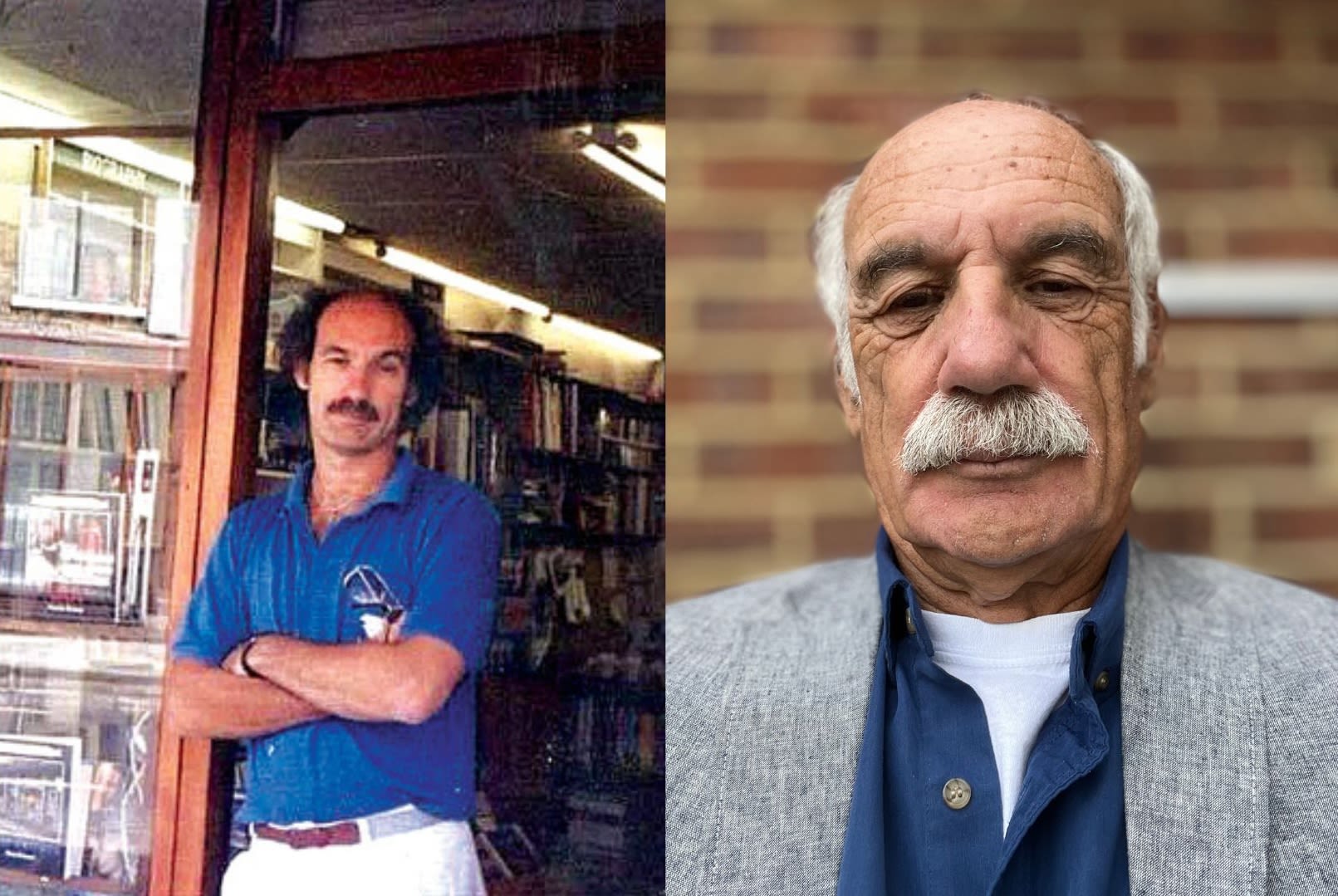

Peter Bergman, then 27, driving home in his Capri to Golders Green from the bookshop he ran in Camden Town, said: “You couldn’t see, it was a fog of rain. It was just thundering down.”

David Smart explains the science behind the intense rainfall

David Smart explains the science behind the intense rainfall

Back in the station, the rising floodwaters had reached the children’s waists, and they were helped onto a low wall in the station by concerned adults.

Sheltering alongside 10 others, the two children watched the waters reach the height of letterboxes and windows.

April, the older sister, said: “We thought it was fun at first, but then it started to get worrying when the water came up to our ankles, even up on the wall.

“I have never seen water like it in this country, before or since. I have lived in India for many years, and it was on the level of a monsoon.”

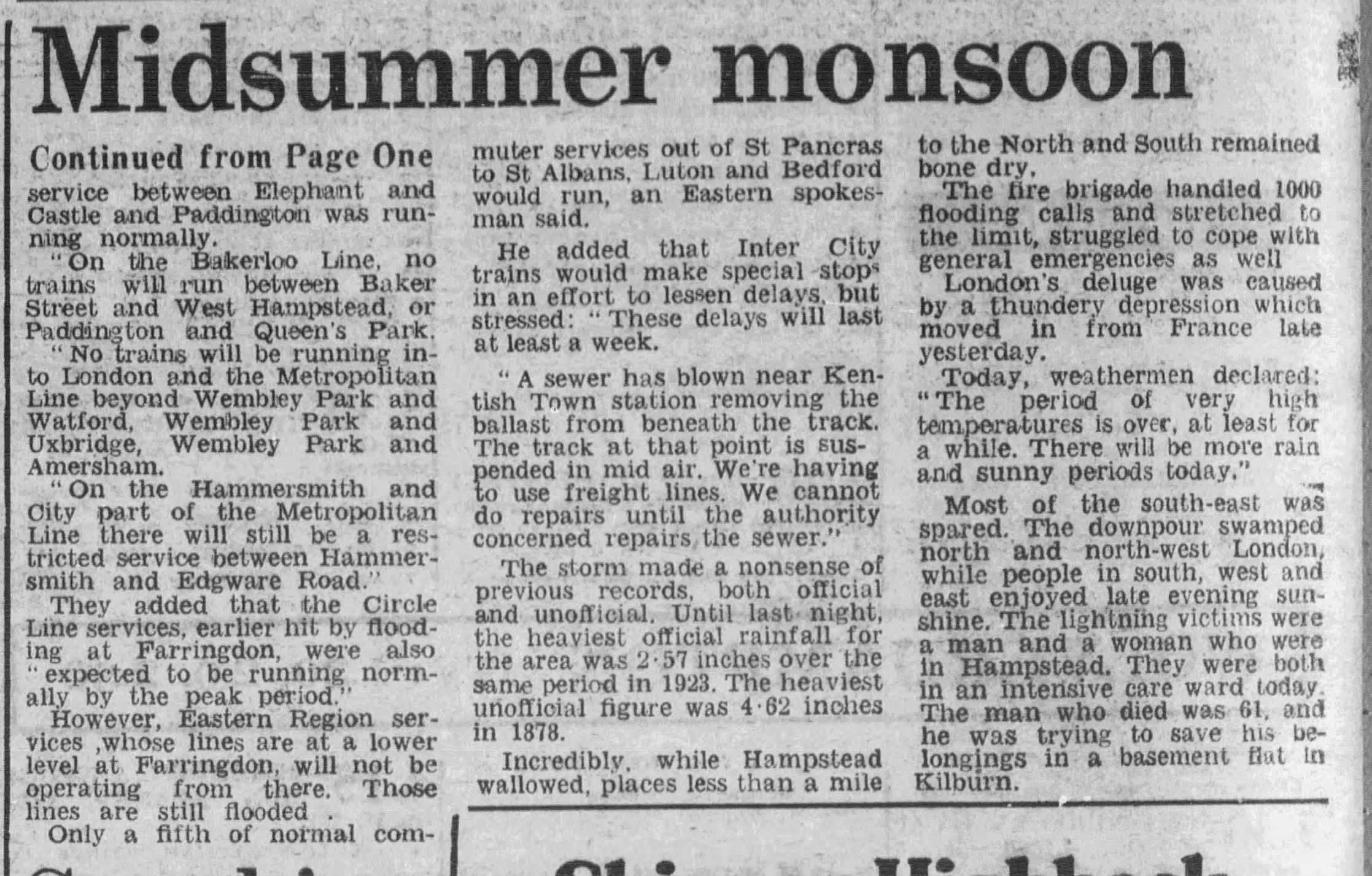

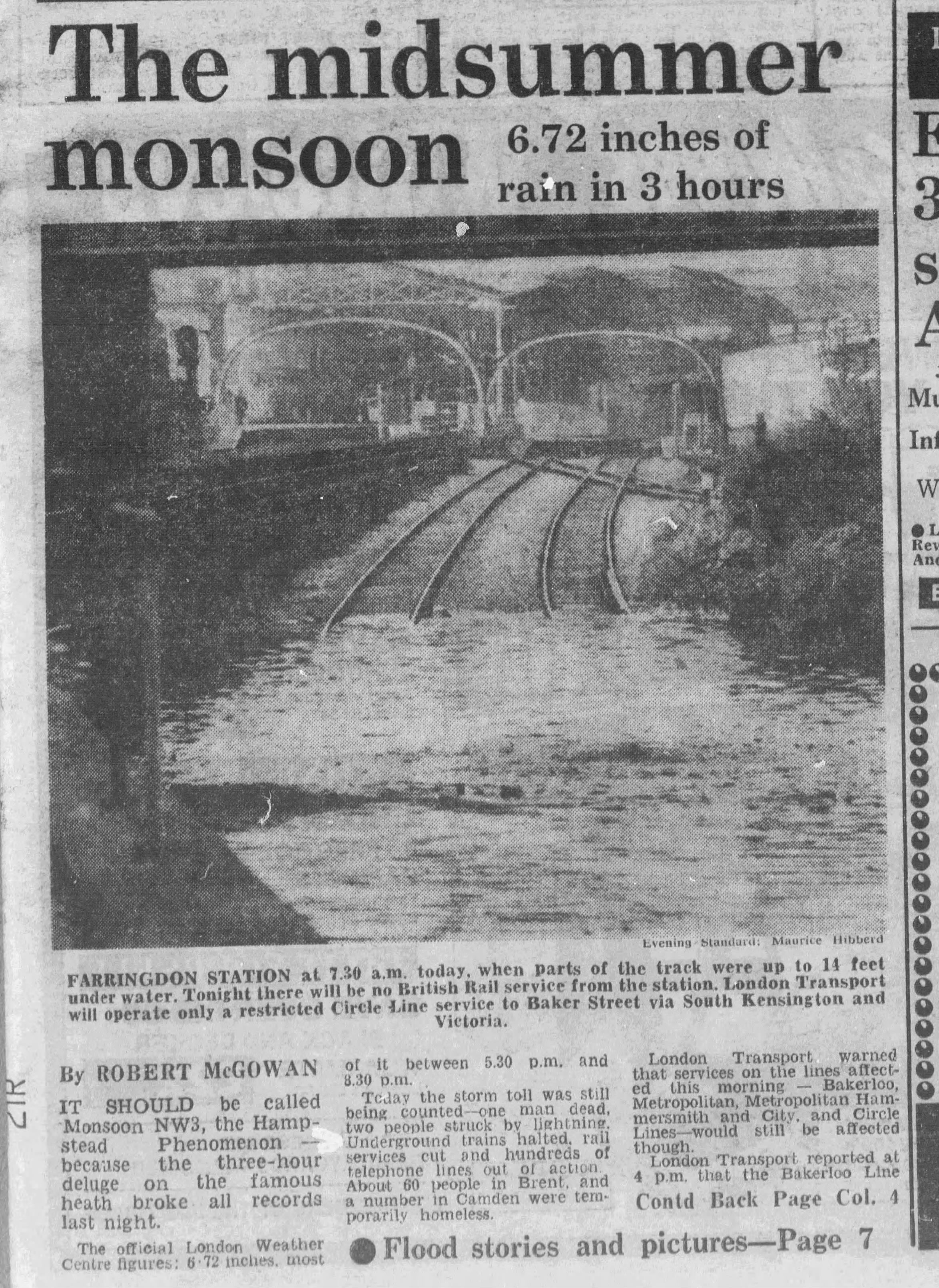

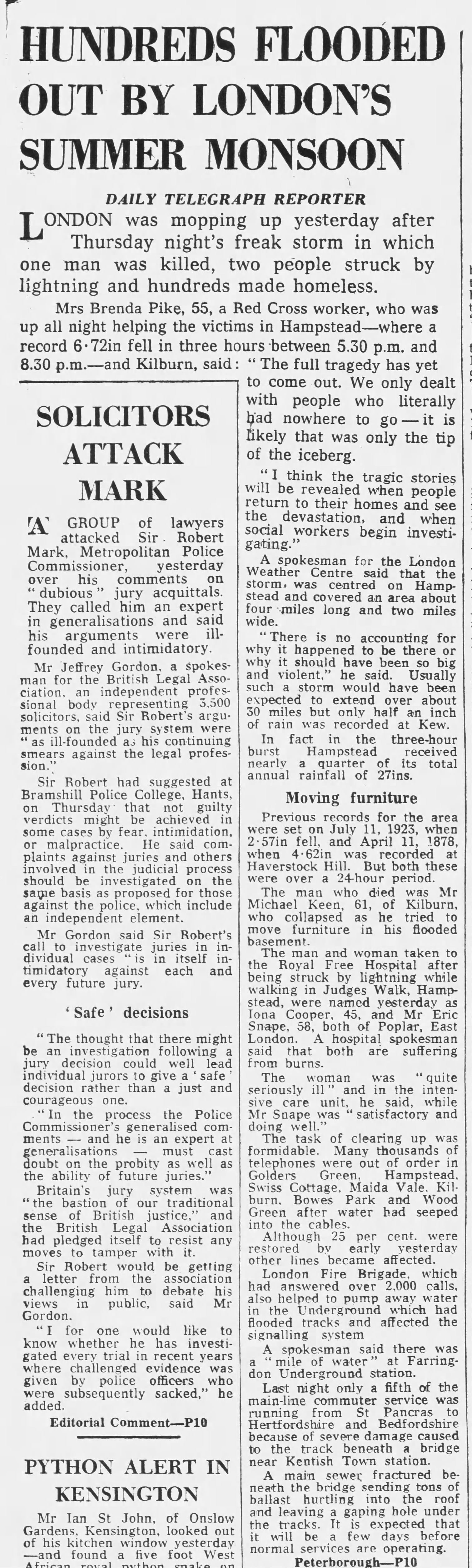

While making headlines at the time, this fame was not to last | Image Credit: Daily Telegraph

While making headlines at the time, this fame was not to last | Image Credit: Daily Telegraph

The synoptic situation over the British Isles at 12 GMT on 14 August 1975 | Image credit : Met Office

The synoptic situation over the British Isles at 12 GMT on 14 August 1975 | Image credit : Met Office

Surface streamline analyses for 14 August 1975 | Image credit : Met Office

Surface streamline analyses for 14 August 1975 | Image credit : Met Office

Weather chart for 1200 UTC on 14 August 1975 | Image credit : Met Office

Weather chart for 1200 UTC on 14 August 1975 | Image credit : Met Office

Isohyetal (lines of equal rainfall) analysis (mm) for 14 August 1975 | Image credit : Met Office

Isohyetal (lines of equal rainfall) analysis (mm) for 14 August 1975 | Image credit : Met Office

The heart of the storm

Beer barrels, boats and underwater cars

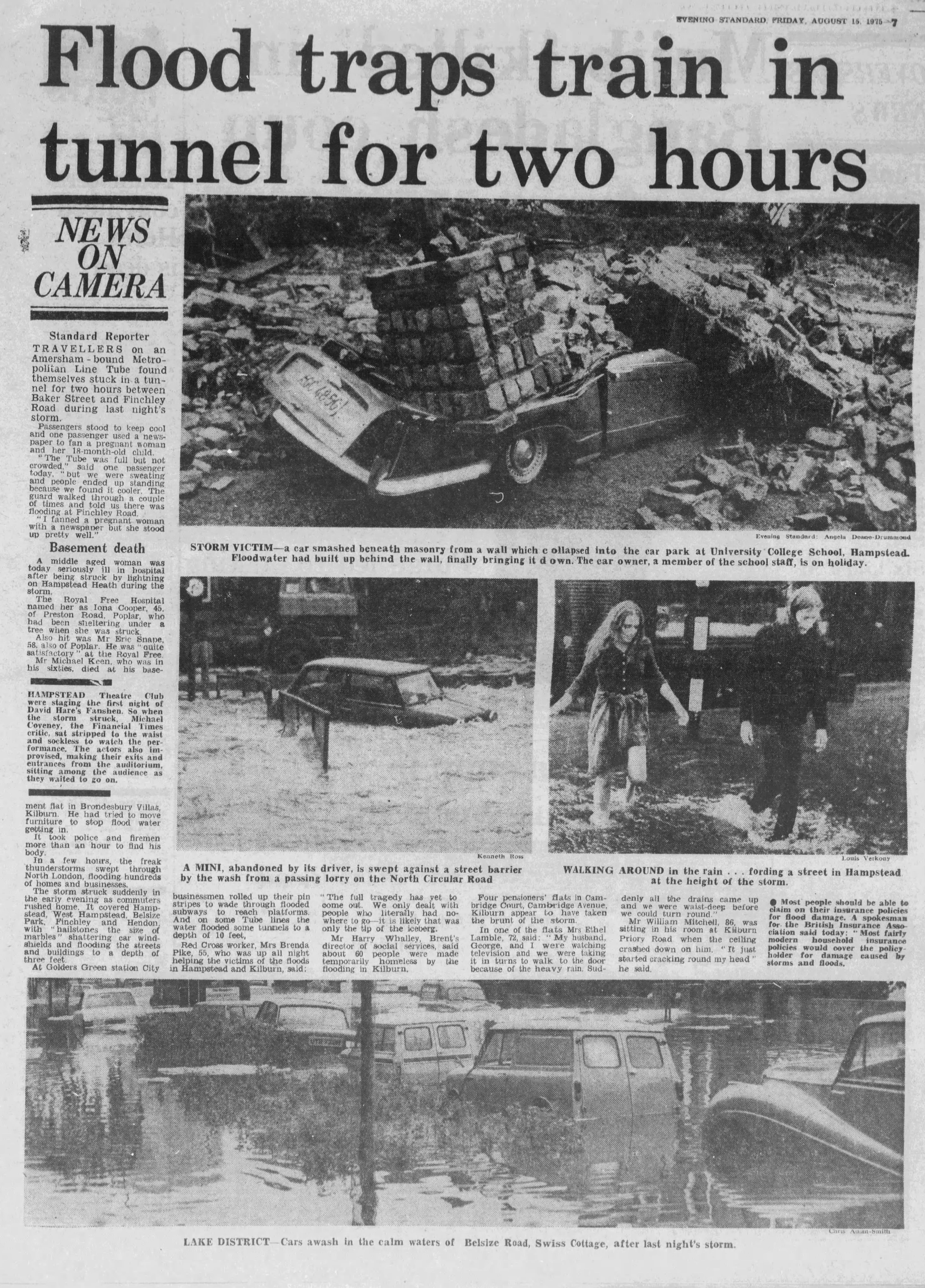

At the Old Oak pub opposite the station, the situation was getting worse by the minute.

Rising floodwaters leaked into the cellar, beer barrels pushed ever skyward and jammed up against the cellar doors.

Reaching bursting point with an almighty crack, the cellar doors split apart, sending beer barrels shooting into the sullen sky, coming down with a plop into the submerged streets.

Bad day for pub owners. Great day for pub-goers.

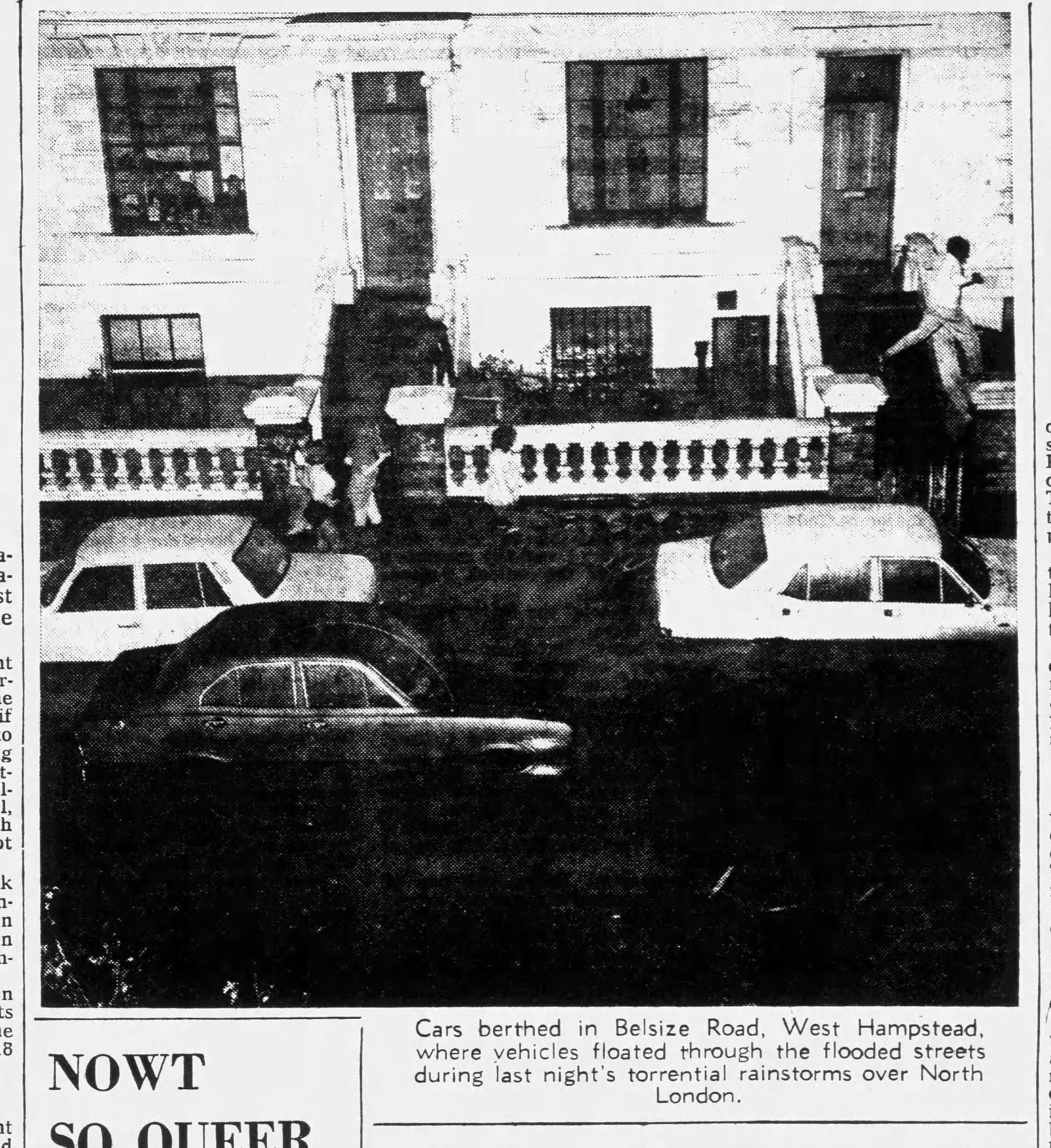

The barrels floated down the street, past cars that were being pulled under.

Tony said: “Most of the cars were either underwater or semi-underwater. A couple of VW camper vans were even floating down the road.”

John added: “Cars were floating down the road past us.”

Bergman was in one such car, although half a mile away on Fleet Road, near the Royal Free Hospital.

Then and now: Peter Bergman | Image credit: Peter Bergman

Then and now: Peter Bergman | Image credit: Peter Bergman

Peter suddenly saw the sky turn black and the rain come pouring down.

Soon, two and a half feet of water covered the surface of Fleet Road

Peter said: “The car in front of me had stopped, then it began to drift across the road.

“I learned that day it doesn’t take much to float a car. They’re boats before they sink.

“A fountain of water shot up through my gearbox, and then before I knew it, I was afloat too. Steering made no difference; I was in a boat.”

Worse lay ahead, however.

Peter added that a new “Lake Hampstead” had formed in the dip in the land around South End Green up towards Hampstead Heath station, with the water “almost 7 feet deep”, according to Bergman.

He said: “There was standing water as far as the eye could see.

“You could just make out a car roof just poking out from above the water line.”

Narrowly avoiding sailing into the lake, Bergman’s new

car-boat drifted sideways, making landfall on Pond Street, and by some miracle, gained enough traction on the waterlogged road to climb the hill to safety.

Road swimmers

Back in Gospel Oak station, occasional swimmers-by crossed the paths of the Weller stragglers, as the skies began to darken.

One of these swimmers may have been Tony May, as he was forced to swim to Queen’s Crescent.

Tony May then, and now under a new raincloud outside Parliament Hill Fields Lido (2026) | Image Credit: Tony May

Tony May then, and now under a new raincloud outside Parliament Hill Fields Lido (2026) | Image Credit: Tony May

He said: “I was living on Glenhurst Avenue at the time, so I was unaffected, but my friend lived in a basement flat in Queen’s Crescent, so I thought I had better go see how he was.

“I ended up swimming down the Gordon House road, and my friend’s basement was completely flooded.”

Maureen Fisher’s in-laws, Claude and Lily Fisher, lived at 11 Barrington Court, where the flooding came up to 1 metre and destroyed everything on the ground floor.

Maureen said: “My in-laws were in their 60s, and no help was given to remove all the damaged goods or help to clean up the property.

“We had to scrub everything down; the floor, walls, doors and up to a metre up the stairs, as well as remove all the furniture.

“They were so traumatised, they just couldn't cope."

Fisher added that her in-laws were insured, but there was no compensation for the loss of personal items, such as wedding photos and birthday cards.

“They were so traumatised, they just couldn't cope”

Image credit: Evening Standard Report 1975

Image credit: Evening Standard Report 1975

Image credit: Daily Telegraph

Image credit: Daily Telegraph

Image credit: Daily Telegraph

Image credit: Daily Telegraph

The journey home

At around 8 pm, when the rain had finally stopped, the Weller children, whose excitement was wearing off, remembered that their mother was expecting them home.

A kindly gentleman offered to help them get there.

The children were unable to take their usual route through Oak Village due to the newly formed “Lake Gospel Oak”, as John dubbed it, where there were reports of rowing boats ferrying stranded people.

Along with their companion and protector, the children squelched, waded and swam round to Lismore Circus and into Grafton Road and home, taking the longer, safer way round.

As John and April finally came in sight of home, they saw the silhouette of their frantic mother, desperately waiting for their safe return.

Eager hugs were exchanged, and a once-over was carried out to check there was no damage to her offspring.

Then one question rang out from the frightened mother that terrified the children more than any flood water:

“If you could have walked home, why didn’t you do it two bloody hours ago?!”

After making sheepish excuses, the children got dried off and refrained from discussing the event with each other, fearing a vengeful mother’s retribution for her unnecessary worry.

Daily Telegraph Report 1975 | Image credit: Daily Telegraph

Daily Telegraph Report 1975 | Image credit: Daily Telegraph

Image credit: Evening Standard

Image credit: Evening Standard

Image credit: Evening Standard

Image credit: Evening Standard

The aftermath

As the dawn broke on a new day, the flood waters had largely receded, disappearing back into the ground without a trace, belying the fact that it had ever really happened.

Yet there was one reported death in a flooded basement and two people injured after being struck by lightning while sheltering beneath a tree.

A summary of the storm damage

A summary of the storm damage

As the summer ended and the Wellers returned to school, they asked everyone they knew:

Were you there?

Did you see it, the flood?

What do you mean, ‘What flood?'

Yet with so many of their classmates away for the holidays, and the dawn of social media and camera phones still a twinkle in a tech company’s eye, few people saw it.

You were either there or you weren’t. You saw it, or you didn’t.

Helen Marcus, then vice president of the Heath and Hampstead Society, once described it as an “urban myth”, while John said: “It's like it never happened. April and I never discussed it until 45 years later.

“It was like being in a dream, maybe some sort of PTSD.”

Yet, upon the very wall where the two children had watched the waters rise, its murky depths inches below them, a dark brown tide mark was left on the wall.

An indelible reminder of a storm whose memory had faded until it was painted over 10 years after the storm, removing even that small reminder for good.

While the Hampstead Storm has faded out of popular memory, eclipsed by major weather events like the "Big Freezes" of 1981 and 1982, it has had a much greater impact on the meteorological and academic community.

Dubbed "Hampstead 75" by academics, it has become a comparison point for other storms of its type and has been the subject of numerous academic papers, research, and studies.

Met Office Academic Researcher J.F. Keers stated that there was a “1 in 20,000 chance” of a storm of this magnitude occurring, and that it was the “most notable event of its kind.”

Professor Christopher Collier of the School of Earth and Environment, University of Leeds, described the storm as an “extreme event” and created an in-depth analysis of the weather patterns that led to the severity of the storm.

Yet for those two young children, the flood was simply a wonderful summer adventure.