Long delays, poor mental health and staff shortages: is now the time to let people seeking asylum work?

For many people in the UK it is hard to imagine being banned from working.

And then, despite being keen to find a job, use your skills and earn a wage, have no choice but to live off the £5.66 a day given to you by the Government.

However, that’s the reality for many people seeking asylum across the UK.

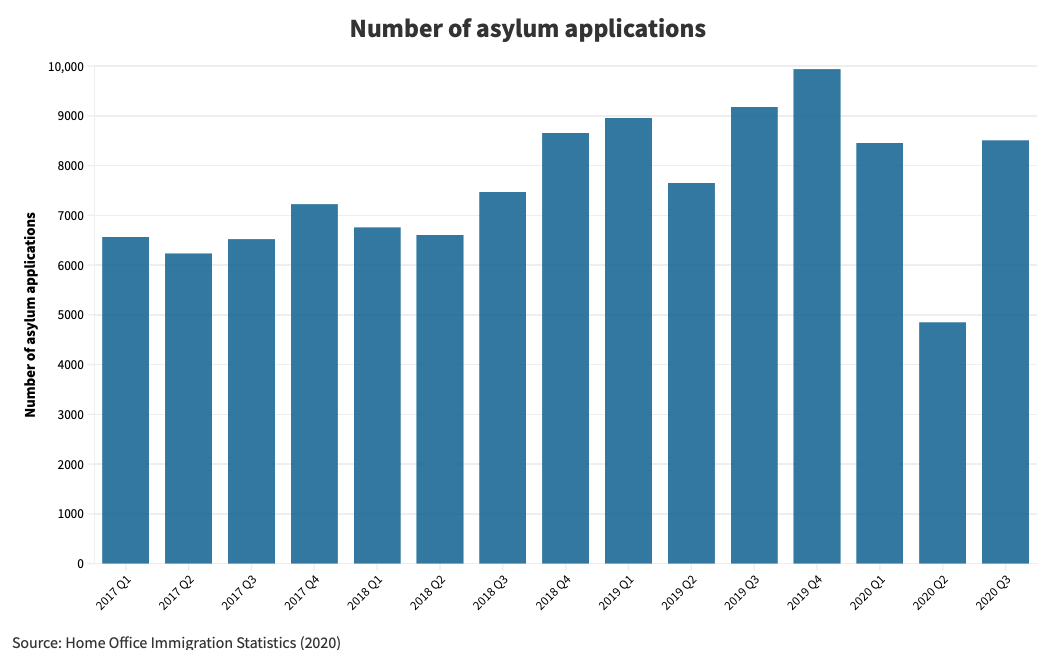

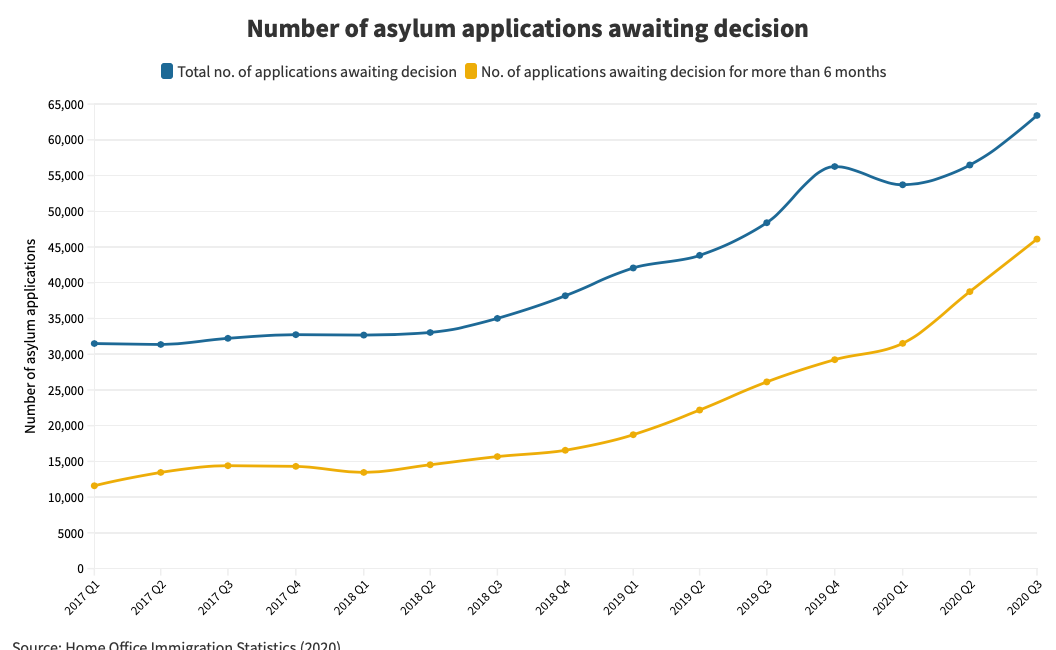

This is made even more challenging by the increasing delays in processing asylum applications.

Currently, of the 60,548 people waiting for a decision on their asylum application, a record 76% have been waiting for more than six months.

In the first 12 months after arriving in the UK, people seeking asylum cannot work.

After this, until they have their application granted, they can only work in jobs which are on the Government’s restricted Shortage Occupation List.

The Lift The Ban coalition is formed of 240 members from charities, trade unions, businesses, faith groups and think tanks and it believes the list is too restrictive.

The group is lobbying the government to allow people seeking asylum the right to work in any job if they have been waiting for more than six months for a decision on their asylum claim.

What is the impact of not working on people seeking asylum?

When people seeking asylum arrive in the UK they can face a number of challenges.

Refugee Council director of advocacy Lisa Doyle said: “They will be in an unfamiliar country, they often don’t speak much English and they have to navigate all sorts of processes that will be really unfamiliar to them.

“Their fate is in the hands of somebody else and that can be quite a lonely and isolating time. Without the opportunity to work people can be stuck without meaningful activity and without a chance to focus on something positive.”

Work is often a key part of a person’s identity and without it people can feel degraded and dehumanised.

A recent Lift the Ban report said unemployed people in the asylum system were more than twice as likely to have major depressive disorder.

As well as being increasingly vulnerable to exploitative labour, due to long periods spent in poverty without the right to work.

What are the arguments for lifting the ban?

For many advocacy groups, allowing those seeking asylum to work can improve their mental health, provide huge social benefits and make their transition to life in the UK much easier.

Ms Doyle said: “It allows people to start to integrate into their communities a lot more. Working will help to improve their English language skills, they will make new friends and they will have colleagues.

“People come into this country with a whole load of skills and if we are not allowing them to use them then people’s skills can erode if they are in specific lines of work.”

For the Refugee Council this is especially important during the coronavirus pandemic.

Ms Doyle added: “There are clearly many people who come who have a background in health and social care and could be key workers.

“By not allowing people to use their skills to do that key work, when it is really needed and valued, just seems really sad and a waste.”

According to the Lift the Ban coalition the UK government could make £97.8 million per year if half of the people who are waiting more than six months for a decision on their asylum application were able to work full time on the national average wage.

However, there are vocal oponents of removing the ban on working.

In a recent parliamentary debate Home Office minister Chris Philp said there are already legal routes to the UK and people seeking asylum should use those.

He also claimed that by lifting the ban on working you could create a pull factor.

Mr Philp said: “If people know that they are able to come here on, for example, a small boat or the back of a lorry, or on an aeroplane, without proper documentation and immediately, or very nearly immediately, start working, that will act as a further encouragement to come.”

However, a University of Warwick study showed that there is little to no evidence of a link between where people seek asylum and economic rights.

Rukayat's story

Rukayat, 29, fled from Nigeria to the UK in 2006 and now lives in London.

However, her application was not granted until September this year.

The past 14 years have had a massive strain on her own and her children's mental health.

She said: “I had to live with stress, anxiety and instability for myself and my children. Not knowing what the future is going to be like, it was stressful.”

Rukayat has three children; two sons aged eight and five and a two-year-old daughter.

Her oldest son has lived in ten different homes as the family were repeatedly moved.

Rukayat said that the accommodation did not feel secure and she used to sleep anxiously every night and wake up worried that someone would be in their room.

She believes if she could have worked her life would have been very different.

Rukayat said: “I would have been an amazing mum that could afford things for the children, I would have achieved things that could contribute to the economy, I would have been one of the great female engineers and I would have gone to university.

“If there were no barriers about working then I would not be facing the barriers I am today and I would have contributed so I wouldn’t be dependent on the government’s benefits.”

Rukayat volunteers for a number of different projects including her local foodbank, Refugee Action, the Magpie Project and the Happy Baby Community.

She initially had mixed feelings when she was granted permission to remain due to the lengthy wait she had faced.

It wasn’t until she told her son that they had been granted permission to stay in the UK, and he burst into tears, that it really hit home for Rukayat.

She said: “When he was crying it clicked in my head and I realised that we have it now. That was when our full emotions just came out. Then I started realising it has actually happened!”

You can find out more about the Lift the Ban campaign here and the work of the Refugee Council here.