MRKH: Living Without a Uterus

The chances are that you haven’t heard of Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome. There’s no shame in that, as nor have a considerable number of doctors.

Also known as Müllerian Agenesis or Rokitansky syndrome, in simple terms MRKH is an underdevelopment of the female reproductive system.

Effecting roughly one in 5000 female births, it is still not known what truly causes the condition, which means those with it do not get periods and cannot carry their own children.

There are two types of MRKH, of which type 1 is the more common. This presents itself as the underdevelopment or absence of the uterus and shortening of the vaginal canal.

Meanwhile type 2, which accounts for around 20% of cases, comes with additional impacts: 40% will experience differences in development of their kidneys, whilst 10% suffer bone changes such as scoliosis, and partial or complete deafness.

Charlie's story

Charlie Bishop, 37, director of charity MRKH Connect, was diagnosed with MRKH when she was 17.

“I’d gone to the doctors when I was 16 because I hadn’t started my period,” Charlie says. “My doctor said: ‘Leave it a year, it’s fine, nothing to worry about right now’, then I went back and she was like: ‘OK, we’ll send you for some tests.’

“I had various tests from ultrasounds, to blood tests, they even put me on the pill as well just to see whether that would kick start anything, in the end it came back inconclusive.

“Then they did a laparoscopy, which is like a little tiny camera that goes through your belly button, had a look around and that’s when they saw that I didn’t have a uterus.”

Charlie was diagnosed when she was 17. Credit: Charlie Bishop

Charlie was diagnosed when she was 17. Credit: Charlie Bishop

Technically infertile, those with MKRH do however usually have functioning ovaries, and through advancements in technology have several options available should they decide to have children.

Charlie says IVF surrogacy is often the preferred route for those with MRKH who wish to have children, since it gives the opportunity to have a child that is biologically theirs, however there are still challenges.

If you are struggling to conceive with a functioning uterus, there is a reasonable chance in the UK, albeit a postcode lottery still, local NHS Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) will support at least one or two free rounds of IVF. Things are however not so simple for those with MRKH.

“It’s very challenging to get funding support through IVF if you need to use a surrogate,” Charlie says. “The condition is often considered rare, but not rare enough, and the complexity of adding a surrogate once the embryo has been created seems to complicate things further making it a very challenging and stressful process that can also have a heavy cost for intended parents.”

“Those with MRKH feel like they’re being isolated or penalised.

“They can’t do anything about the fact that they’re born without a womb.”

A further complication is that some countries, such as France, Germany, Italy and Spain, do not legally allow surrogacy, leaving adoption as the only choice for those wishing to start a family unless they travel abroad.

However, childbirth is only one effect of MRKH, with the condition also impacting sex lives and more importantly feelings about body image.

“When you’re taught in school about sex, a lot of that is about penetration. Then you find out with MRKH that you have a shortened vagina and it’s going to be quite difficult.

“I think it’s kind of drilled into us that there is almost something wrong with your body because you can’t do that. It alienates you as a teenager when you’re of that age where you’re developing, you’re chatting to your mates and you’re not having those same experiences in the same way.”

Those with MRKH can still enjoy a happy and loving sex life. Credit: pttgogofish via Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0)

Those with MRKH can still enjoy a happy and loving sex life. Credit: pttgogofish via Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0)

Charlie outlines that there are options for treatment to support penetrative sex, but it is a choice not a requirement. One of those options is dilation, but she wants to see more to normalise the conversations about our bodies.

“As soon as you mention the word ‘vagina’, people get very awkward and embarrassed about sharing that. It feels like something that shouldn’t be talked about because it’s a private part of your body.

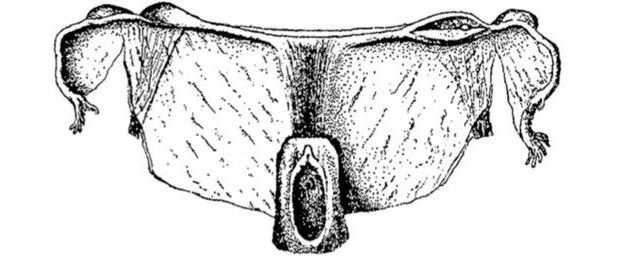

Carl von Rokitansky's 1838 diagram showing the reproductive system of a female with MRKH. Credit: OJRD

Carl von Rokitansky's 1838 diagram showing the reproductive system of a female with MRKH. Credit: OJRD

“That’s one thing we as a community are trying to do more, really normalise the conversation around some of these phrases, and just our bodies in general.

“Then someone who’s going through this who’s only just been diagnosed doesn’t feel so ashamed or isolated or not know how to share this with someone else because they feel embarrassed about saying those kinds of words.”

Charlie, who is from Kent but now works in Tromsø, Norway as a remote sensing scientist, says that currently this stigma can shame those with MRKH and other conditions focused on reproductive health into silence, and greater support needs to be provided.

“MRKH can definitely have an impact on how you feel about yourself.

“Many people say that it actually kind of makes them question their identity.”

“What we’re told are our rights of passage of womanhood, periods and those kinds of things, aren’t the same experience, we don’t have that.

“Then there’s the impact of suddenly being presented with not having children. It’s bringing it to the forefront at an age where you really shouldn’t need to be thinking about that.

“Of course, it causes worry and panic. ‘I’m not good enough, no one’s ever going to love me’, those kinds of questions are quite typical.”

One of the main issues surrounding MRKH is that due to its scarcity, some doctors may go through their entire medical career without ever encountering a case, and are unaware of its existence.

Charlie says: “I had a really good GP and she was really interested, but we hear so many horror stories from twenty years ago to six months ago.

“People have had horrible experiences with GPs just not caring, or not doing the test until they’re being really pushed by a parent or by the girl themselves who wants some answers as things aren’t right.”

MRKH CONNECT

Through MRKH Connect, which was set up by two other women with MRKH in 2014, the charity are hoping to raise more awareness and promote conversation around the condition.

The main mission is to bring those with MRKH together, so they don’t feel isolated and alone, with a safe members only area for those with the condition to chat and share experiences.

Alongside this is raising awareness of the condition, with a big challenge event recently launched called ‘MRKH 5000 in 50’. The aim here is to undertake 5000 hours of activity, from fitness to creative writing, in 50 days.

Our #mrkh5000in50 event is coming in 1 months time and you can now sign up! Join us as we raise awareness of #MRKH across the world! With lots of fun and incentives along the way!

— MRKH Connect (@MRKHConnect) April 6, 2021

Find out more and sign up here https://t.co/vxq0GZh1xF pic.twitter.com/WzwRTbEWZA

“Raising awareness is really important, it shines a light on a community that feels it has a very strong and courageous message to share,” Charlie says.

“They really want to have their voice heard and to make a change so that the next person diagnosed knows there is support out there and in many cases has a better experience than they did.”

If you want to find out more about MRKH or the work of MRKH Connect, you can visit their website at www.mrkhconnect.org or follow them across social media @mrkhconnect.