oh wind cry, let me learn to cry from you

Music brings solace to Uighur survivors of China's Xinjiang human rights abuses

Rahima Mahmut sings in her London kitchen to remember everything that she has lost.

For two decades, the campaigner has used music to draw international attention to the human rights of Uighurs, the ethnic group from western China to which she belongs.

In 2019, she composed a tribute to Uighur poet Chimengul Awut, based on the final message Awut sent before she went missing: "Don't cry son, the world will cry for you."

Yet since losing touch with her family in Xinjiang, which Uighurs call East Turkestan, in 2017, music has also become a unique source of solace.

"Nowhere is like home. Nowhere can compare. I cannot even imagine the faces of the people that I love," she said.

“But music gives me the strength to rise like a phoenix from the ashes, to rise from the sadness."

If you ask me what you miss most in lockdown, I miss our rehearsals. This video was recorded from our rehearsal just before the lockdown. Yighla Shamal, Oh Wind Cry! Lyrics by Chimegul Awut, who has been detained since July 2018. Music composed by Me, arranged by Shortaro Sasaki. pic.twitter.com/xQh2Wm8TpX

— Rahima Mahmut (@MahmutRahima) June 25, 2020

Rahima was not born to be an activist. Her life has made her so.

She and her nine siblings were raised in a house full of music, close to China's border with Kazakhstan.

Rahima loved to sing, but to please her father and secure a career, she studied petrochemical engineering at Dalian University of Technology.

On 2 June 1989, she stood amongst crowds in Tiananmen Square who would, two days later, be murdered by their government.

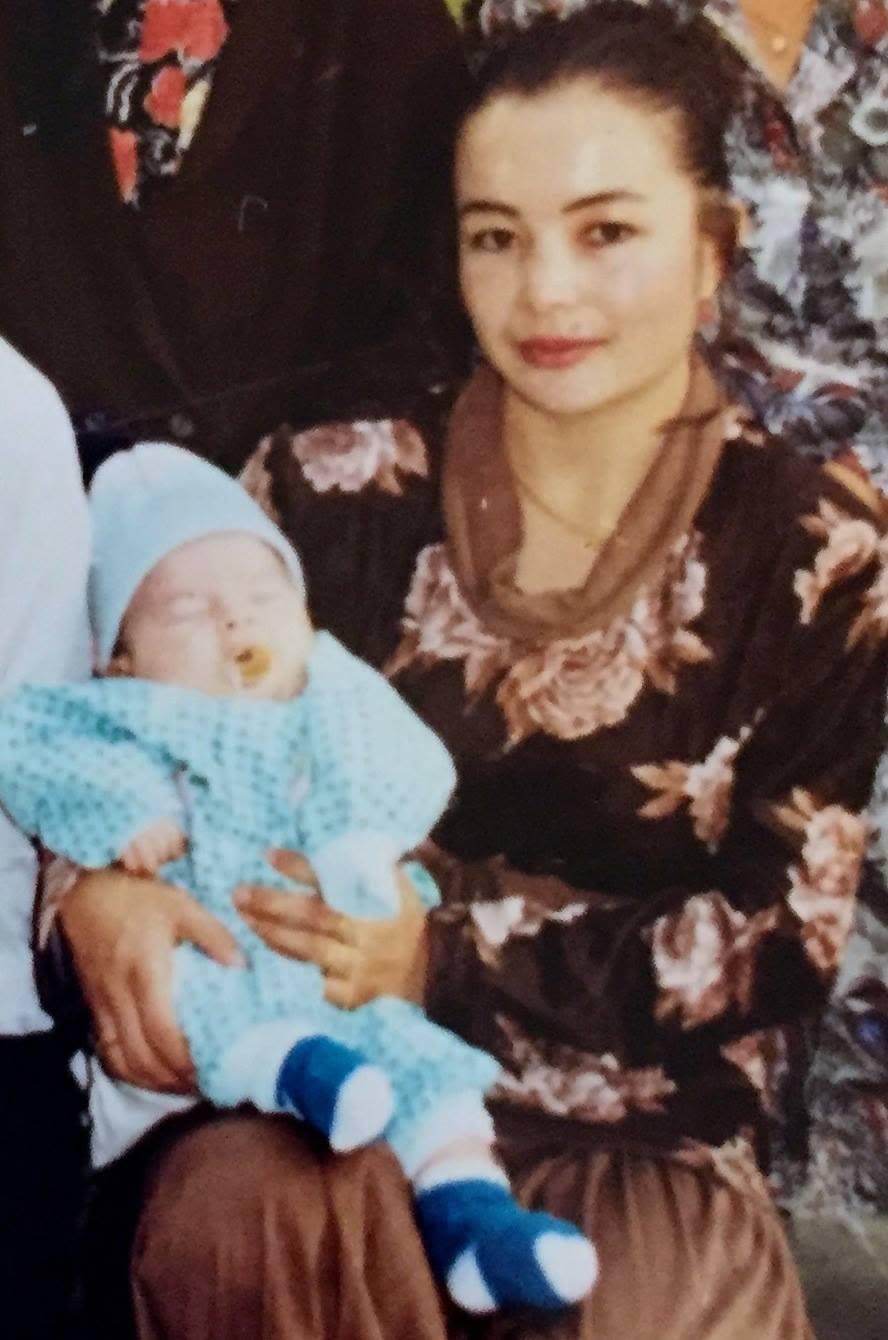

In 1995, as a new mother, she was given an IUD - a form of birth control - in line with a law which said she could not have another child for three years. If she did, she would lose the career she had worked so hard to gain.

Then on 5 February 1997, she witnessed state violence against protestors in her hometown of Ghulja.

“I saw it coming. People were protesting against policies which step-by-step had taken away the rights promised under the constitution.

“They brought in the military, killing and arresting so many. We were marginalised in every way. I couldn’t see any hope,” she said.

In 2000, she fled to London, having witnessed and experienced some of China's worst human rights abuses.

For those left behind, the worst was still to come.

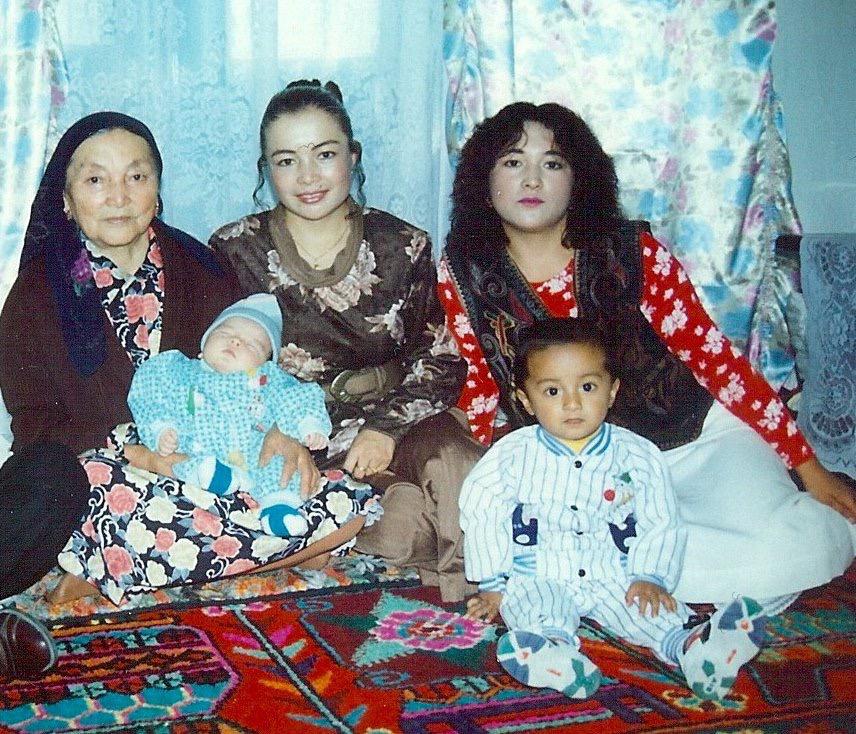

Ghulja, Xinjiang

Ghulja, Xinjiang

Rahima with her son

Rahima with her son

Chinese forces in Ghulja, 1997

Chinese forces in Ghulja, 1997

After Uighur separatists killed 31 people at Xinjiang a train station in 2014, Chinese President Xi Jinping ordered the Communist Party to use the “organs of dictatorship” to tackle extremism.

In a statement made just weeks after and leaked to the New York Times by party insiders in 2019, Xi made his instructions towards the Uighurs clear: “show absolutely no mercy”.

In January 2017, Rahima heard from her family for the last time. Her brother wrote a message: "Leave us in God's hands, we'll leave you in God's hands too."

Official Chinese government figures show that at least 1 million Uighurs have since been detained in what human rights groups call ‘concentration camps’.

China says that the camps, where parents are separated from their children, are to “re-educate” Uighurs by teaching them Mandarin, vocational skills and, where necessary, de-radicalise those with extreme views.

Rune Steenberg, an anthropologist at Columbia University, believes this policy alone would have devastating consequences on Uighur culture.

"Family networks are being targeted and destroyed. Even if some of those in camps were treated well, the destruction of families and the impact on the social system has been enormous," he said.

Yet Halmurat Harri, a Uighur living in Finland, says his parents' case suggests they are part of a more sinister project.

The pair were detained in camp in April 2017. Both over 70 years old, they had no need for vocational training. His father, who as a child had been sent to live with a Han family during the cultural revolution, even spoke fluent Mandarin.

“What happened to Uighur people could happen elsewhere, in other parts of China," said Halmurat.

“This is not only a Uighur issue, it’s not only a religious issue, it’s a human issue.”

After a vocal campaign in Europe, Halmurat's parents were released and put under house arrest. Yet recent evidence shows China's mistreatment of Uighurs continued apace.

Uighur hats, called Doppa. Credit: Uyghur East Turkistan

Uighur hats, called Doppa. Credit: Uyghur East Turkistan

Drone footage leaked from Xinjiang in September 2019 showed Uighur men shaved, blindfolded and handcuffed as they were led onto a train by Chinese authorities.

In June 2020, US scholar Adrian Zenz showed that China's policy of forced sterilisation of women from Uighur and other minorities caused birth rates to drop dramatically.

Growth rates fell by 84% in the two largest Uighur areas between 2015 and 2018, and declined further in several minority regions in 2019.

"These findings provide the strongest evidence yet that Beijing’s policies in Xinjiang meet one of the genocide criteria cited in the U.N. Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, namely that of Section D of Article II: “imposing measures intended to prevent births within the [targeted] group," Dr Zenz said in the report.

Women chatting over a Loom. Credit: Mike Locke

Women chatting over a Loom. Credit: Mike Locke

For Rahima, the information was both welcome and devastating.

“I was overjoyed because it confirmed what we have been telling the world - but the world, it seemed, didn’t listen,” she said.

"It has not learned anything since it promised 75 years ago it would "never again" allow what happened to the Jewish people to take place."

"At the same time, I feel helpless and scared for the people who are still there, including my brothers and sisters," she said.

Rahima's son with his cousin

Rahima's son with his cousin

In response, the US for the first time imposed sanctions by freezing the assets of key Chinese officials involved in human rights abuses in Xinjiang.

In the UK, Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab refused to rule out similar sanctions after accusing China of "gross and egregious" rights abuses against Uighurs.

"I really had tears in my eyes when I heard," said Rahima.

"Even though we have not caught them physically this is quite a big statement that affects their reputation and financial situation.

"I wish I could see them be tried in an international court, but we know we are still a long way from that," she added.

"I don't want you to build a museum to remember Uighurs. I want you to prevent a genocide."

When Rahima and other exiles founded the London Uighur Ensemble in 2004 few Europeans had heard of either Uighurs or Xinjiang.

"People would stare at me, with no idea what I was talking about," she said.

She found solidarity amongst the Jewish communities of North London: one of the few groups who she believes can comprehend the burden Uighur survivors bear.

“Only someone who experienced something similar to this can understand the depths of the pain you feel.

“Your memories - including your childhood - is completely destroyed. One part of you is destroyed," said Rahima.

Yet as she reads new evidence of atrocities against Uighurs every day without respite, music remains her means of keeping Gulja, her home, and those she shared it with, alive.

"When I sing, it lifts me," she said.

"I go to a different place, and I relive the life of my childhood."