Protest and Promise: Race in Sutton Schools

Protest

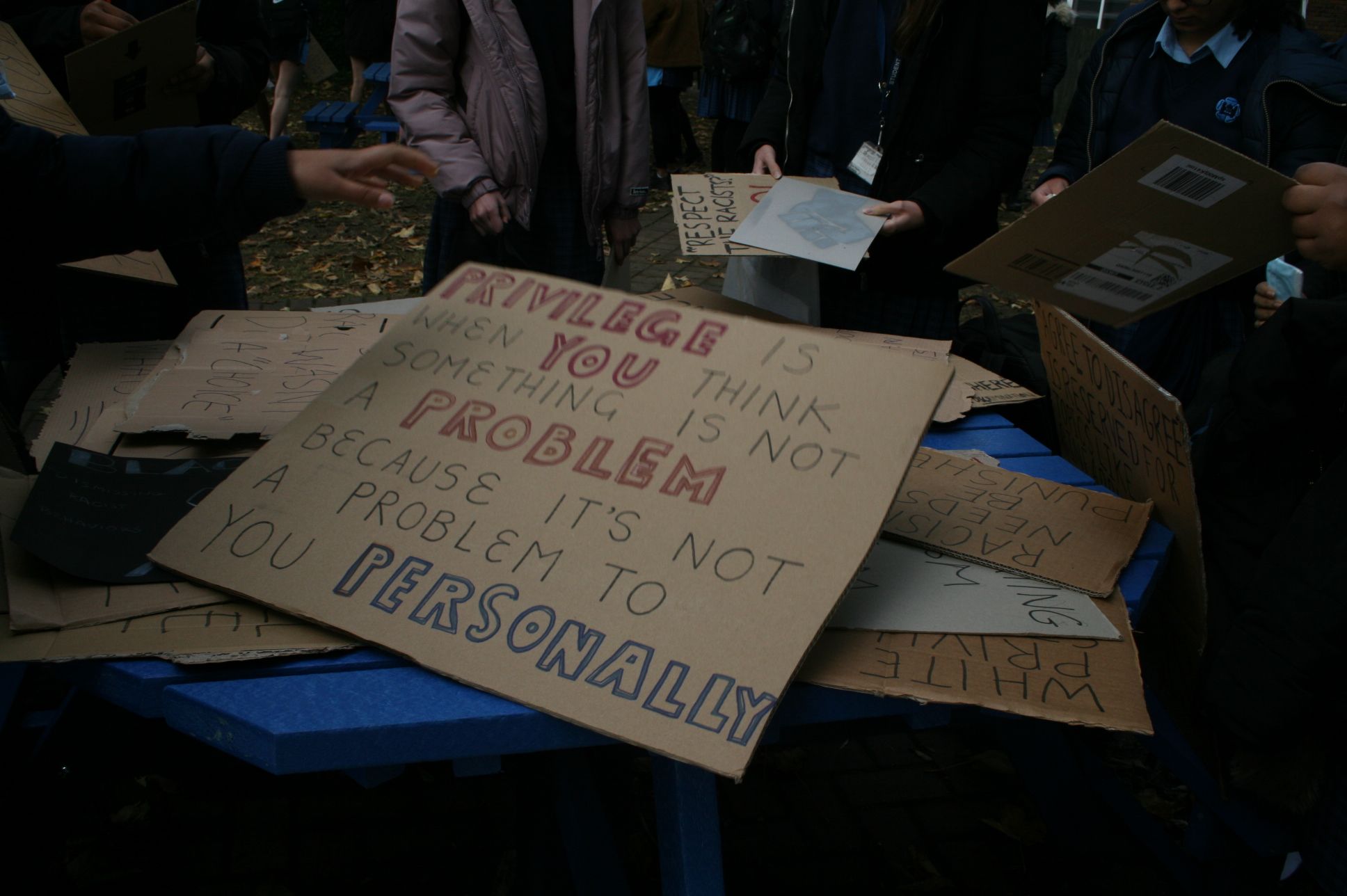

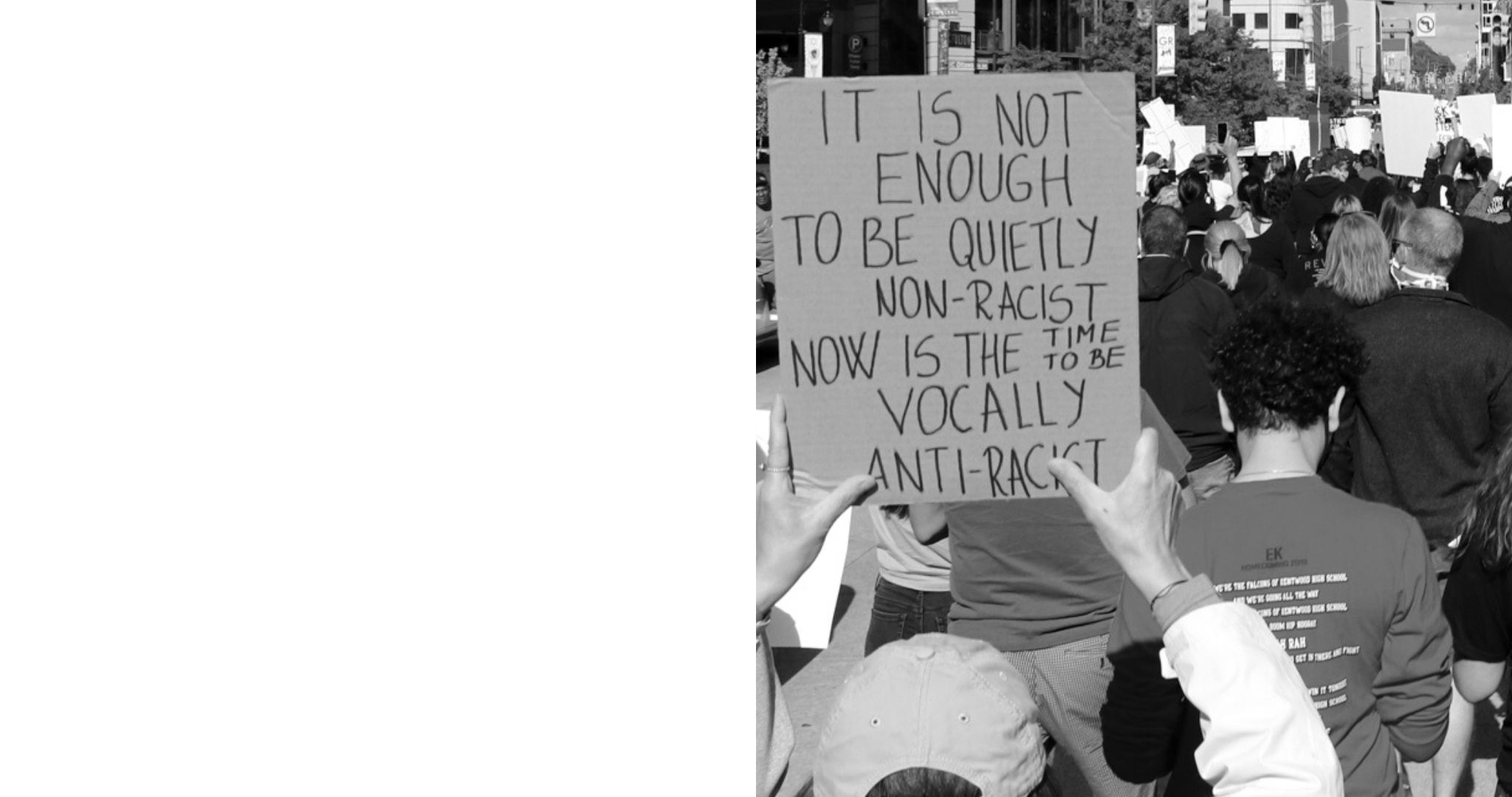

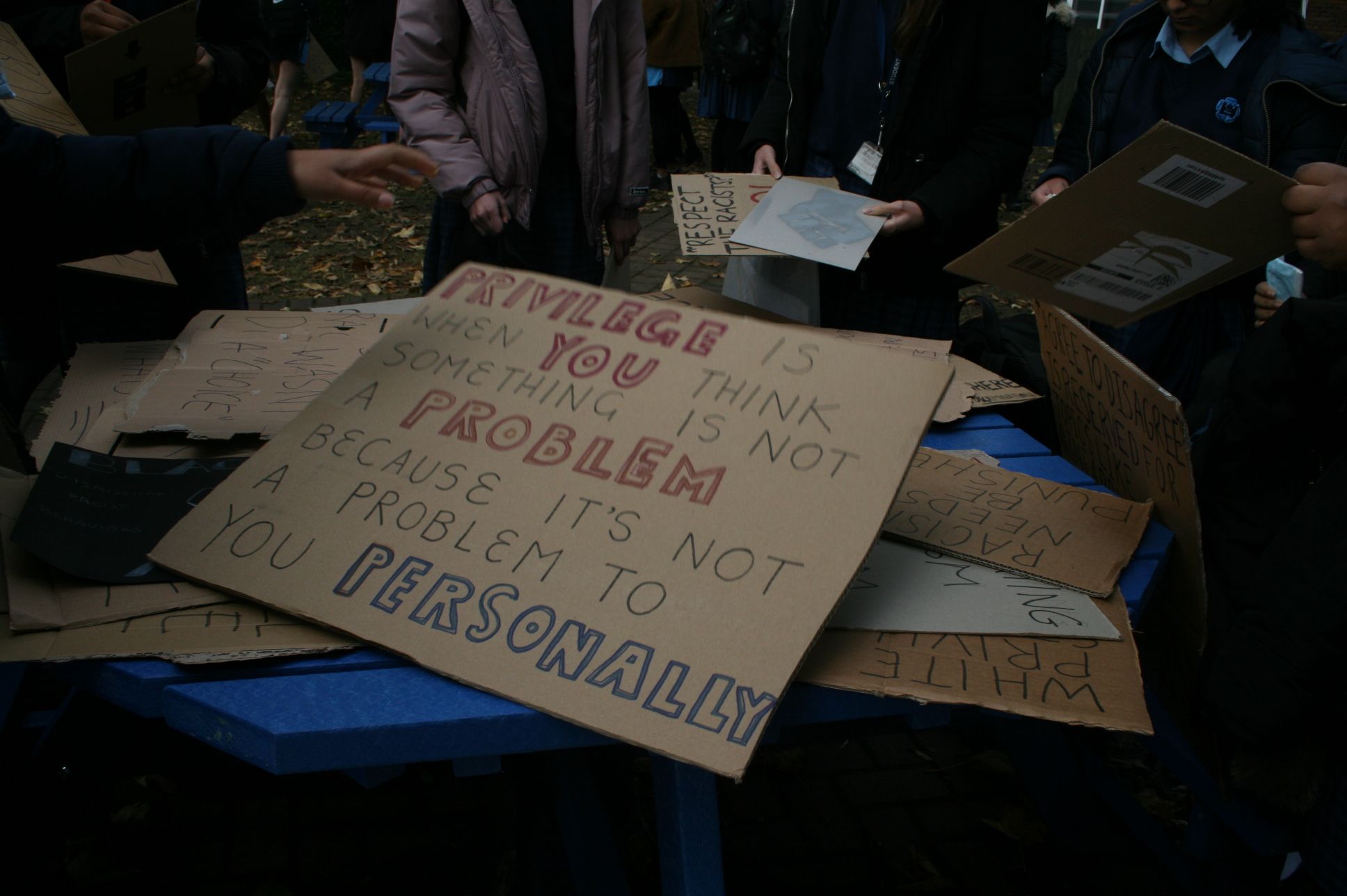

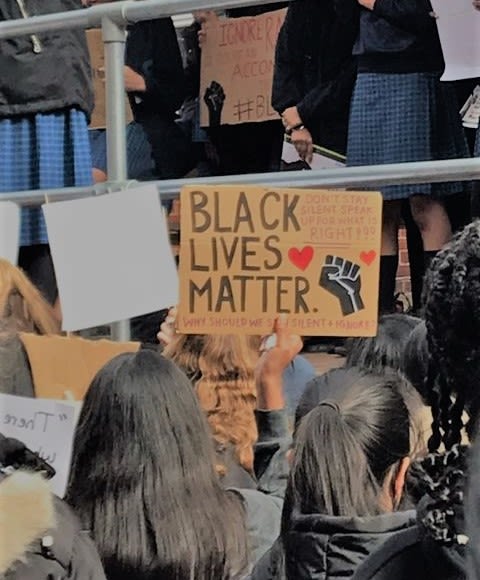

In 2020 protest was contagious.

The murder of George Floyd echoed across the world. People came together, despite the pandemic forcing them apart, to march against racism.

Simultaneously, all parts of society were re-examined through the lens of race: politics, business, history, education.

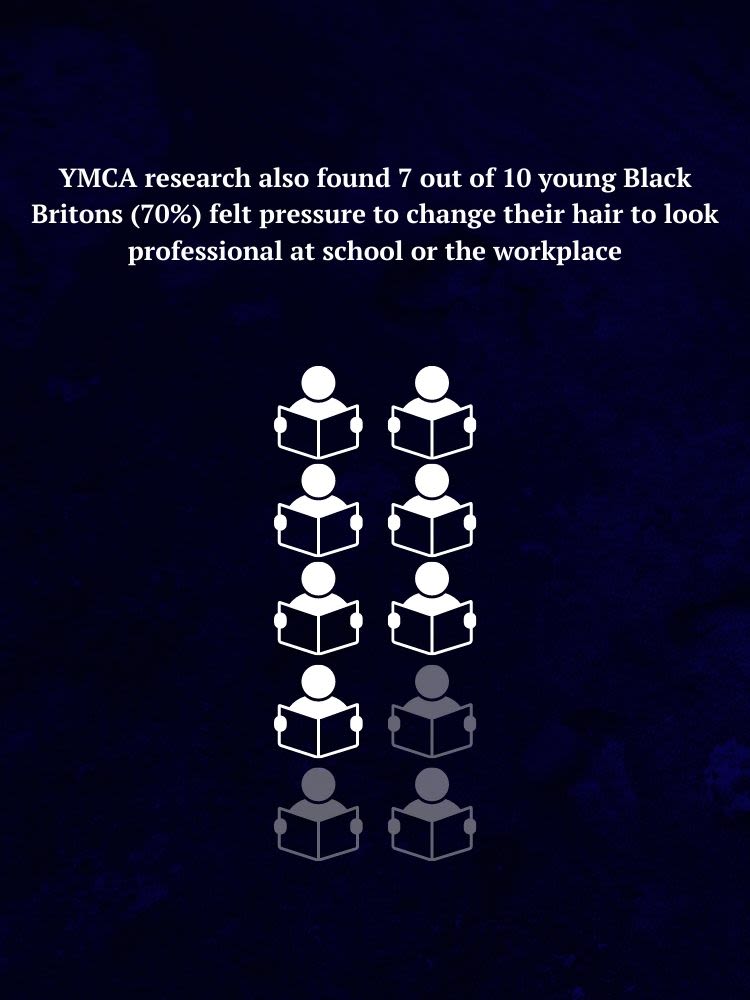

From arguments over decolonising the curriculum to anti-black hair policies, schools became part of the debate.

A Twitter page was set up to document hundreds of racist incidents reported in UK schools.

The stories of two in the London Borough of Sutton during, before, and since that fateful year are a microcosm of how the UK education system continues to grapple with race.

Nonsuch High School for Girls was rocked by explosive protests in October 2020 over teachers' handling of alleged racist comments.

Wilson's School, though suffering less unrest, had current and former students speak out about serious concerns with the school's handling of race issues.

Both highlight important questions about the experience of students of colour.

For example, will schools be forced to give more power to students on the emotive issue of race?

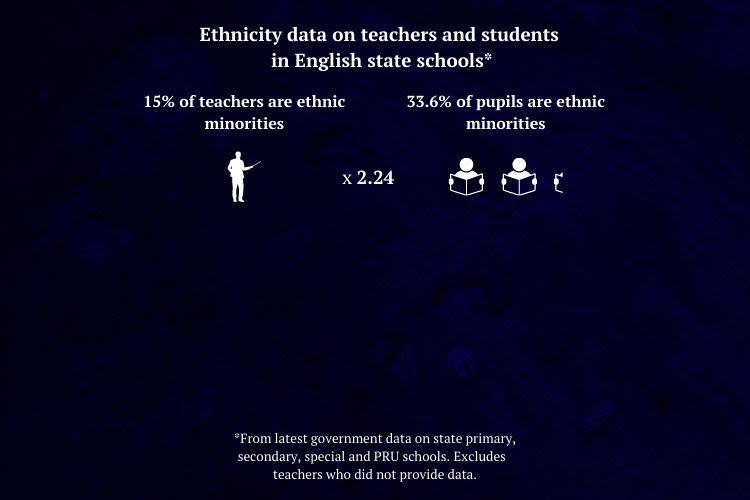

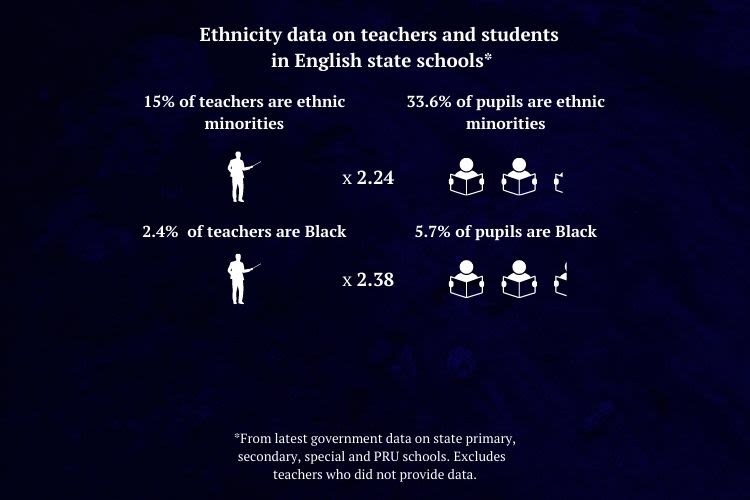

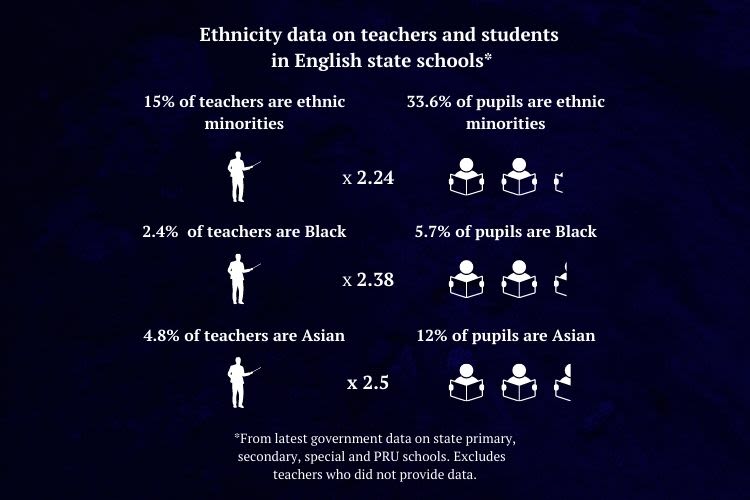

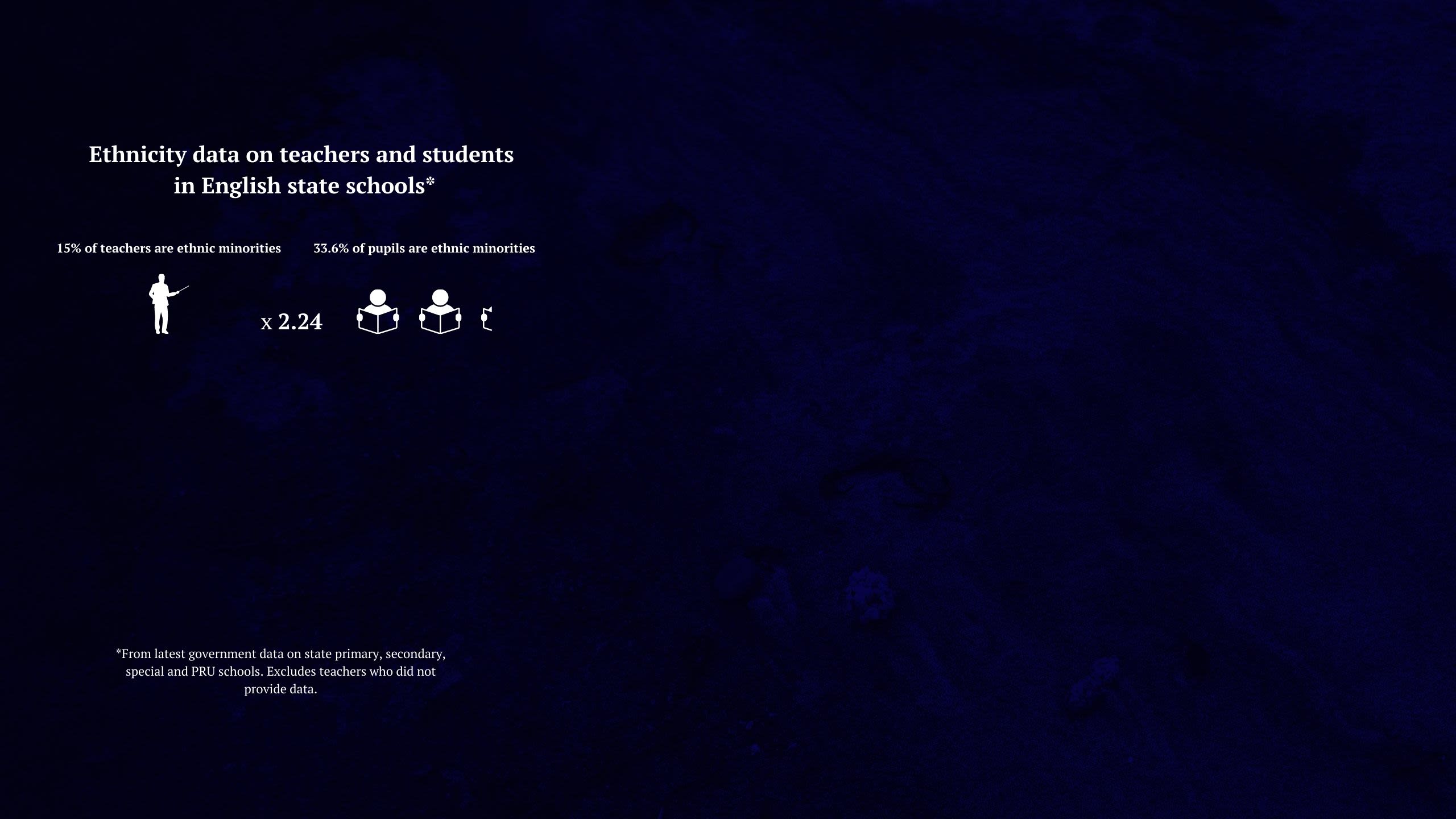

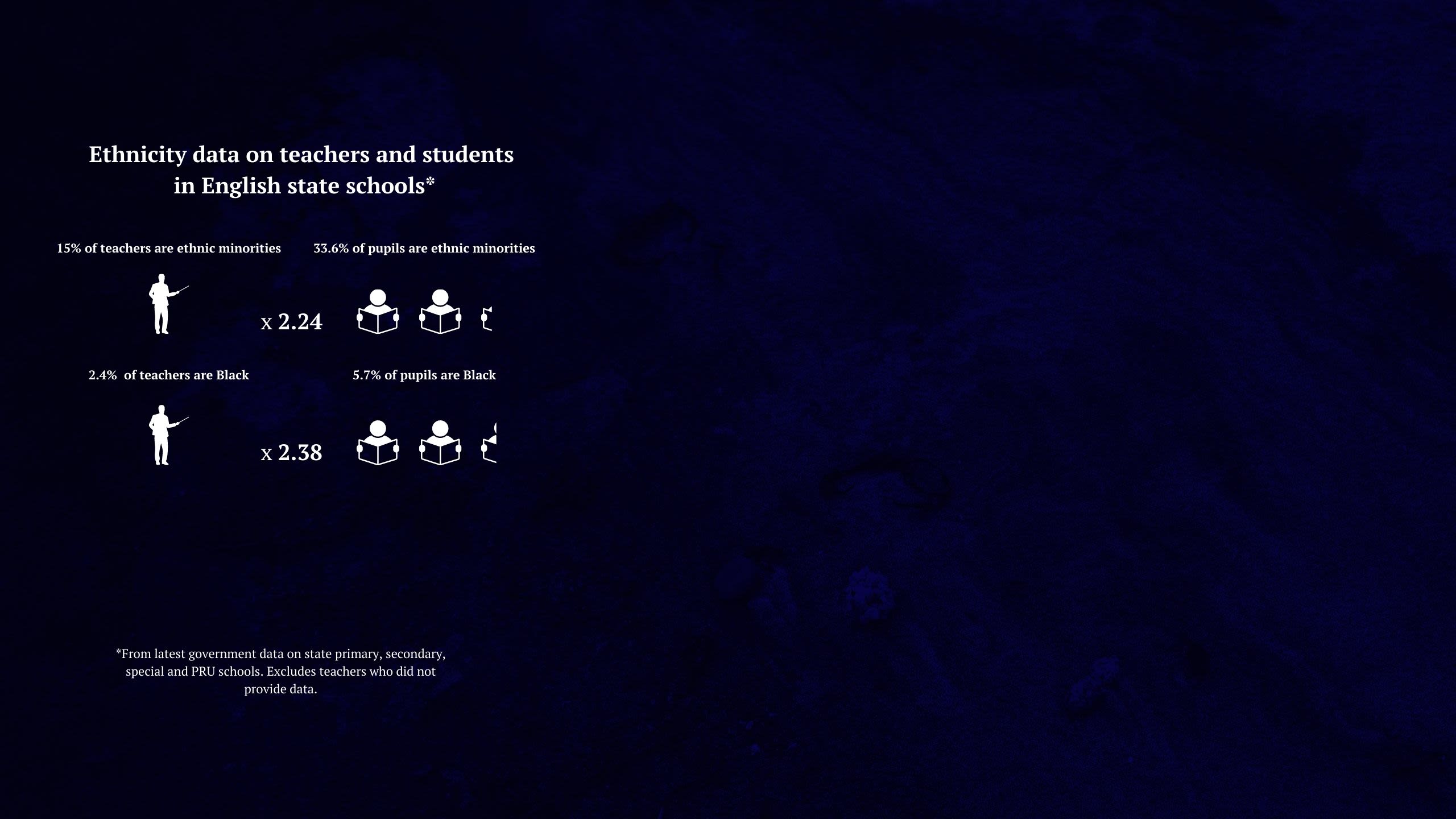

Can we continue having a rapidly diversifying student population, particularly in London, governed by overwhelmingly white teachers?

And, most importantly, where do we go from here?

In 2020 protest was contagious.

The murder of George Floyd echoed across the world. People came together, despite the pandemic forcing them apart, to march against racism.

Simultaneously, all parts of society were re-examined through the lens of race: politics, business, history, education.

From arguments over decolonising the curriculum to anti-black hair policies, schools became part of the debate.

A Twitter page was set up to document hundreds of racist incidents reported in UK schools.

The stories of two in the London Borough of Sutton during, before, and since that fateful year are a microcosm of how the UK education system continues to grapple with race.

Nonsuch High School for Girls was rocked by explosive protests in October 2020 over teachers' handling of alleged racist comments.

Wilson's School, though suffering less unrest, had current and former students speak out about serious concerns with the school's handling of race issues.

Both highlight important questions about the experience of students of colour.

For example, will schools be forced to give more power to students on the emotive issue of race?

Can we continue having a rapidly diversifying student population, particularly in London, governed by overwhelmingly white teachers?

And, most importantly, where do we go from here?

"That overwhelming sense of pride and the emotions that were flying high that day is something I will never experience ever again," Anise Sloper told South West Londoner.

Sloper, 16, was a main organiser of protests which took place on Thursday 15th October 2020 at Nonsuch, a girls grammar school located on the border of Sutton in Cheam.

Nonsuch High School for Girls - Credit: Nonsuch High School for Girls

Nonsuch High School for Girls - Credit: Nonsuch High School for Girls

The preceding events began when a white student allegedly made racist comments on Snapchat in summer 2020, such as the claim the n-word isn't racially insensitive, or black slaves should have just escaped.

The comments were spread on social media, and the student was confronted about them by peers when school started, leading to an assembly on the issue on Tuesday 13th October.

Sloper said: "The school held this assembly, they sat the entire year group down, and basically told us that we had to respect this girl, that we shouldn't be shunning her.

"Not once did they say the word racism in the assembly? Not once did they ever address the situation.

"It's ridiculous that, a headteacher can stand up there, a white head teacher in front of majority people of colour, 15 year olds at the time, and say 'don't be upset that these people are racist'.

"People came out of that assembly actually crying."

In a statement sent by the schools' headteacher, Amy Cavilla, Nonsuch told South West Londoner they were investigating the alleged racist incidents at the time and the assembly, was "an attempt to re-state the school’s stance on anti racism; and ask for the students’ patience while the investigation was ongoing."

After the assembly, Sloper said students started to think how they could rebel after feeling betrayed by the school.

"Previously, most of us had felt empowered and supported."

Anise Sloper - Credit: Anise Sloper

Anise Sloper - Credit: Anise Sloper

They started to compile a dossier of all the racial incidents that had occurred at the school.

It included a white teacher referring to students of colour by their seat coordinates after saying they could not pronounce their names.

It also had the account of a black ex-student who described time in the Combined Cadet Forces (CCF) with boys school Sutton Grammar, in which she was repeatedly called the n-word by white and Asian students, and likened to a gorilla.

By Thursday 15th October, having organised the protest on WhatsApp after students were prevented from sending emails on the school system, everything was in place.

Sloper describes how roughly 20 students gave emotional speeches from a raised canteen platform to hundreds brandishing banners in the school's playground, talking into her phone connected to a Bluetooth speaker.

"Hearing my friends do their speeches, and hearing them say things that everyone resonated with and then everyone would cheer, and everyone would scream and clap.

"Nothing will ever compare. It couldn't have happened without everyone's cooperation. And we'd never pulled together like that."

After the protest, over 900 alumni of the school signed an open letter calling on it to improve its handling of race issues.

"We felt important, which is something that students don't get to feel at school. You know, it's very much you're not in charge here. And for a second we were like, well, we are!" Sloper said.

"That overwhelming sense of pride and the emotions that were flying high that day is something I will never experience ever again," Anise Sloper told South West Londoner.

Sloper, 16, was a main organiser of protests which took place on Thursday 15th October 2020 at Nonsuch, a girls grammar school located on the border of Sutton in Cheam.

Nonsuch High School for Girls - Credit: Nonsuch High School for Girls

Nonsuch High School for Girls - Credit: Nonsuch High School for Girls

The preceding events began when a white student allegedly made racist comments on Snapchat in summer 2020, such as the claim the n-word isn't racially insensitive, or black slaves should have just escaped.

The comments were spread on social media, and the student was confronted about them by peers when school started, leading to an assembly on the issue on Tuesday 13th October.

Sloper said: "The school held this assembly, they sat the entire year group down, and basically told us that we had to respect this girl, that we shouldn't be shunning her.

"Not once did they say the word racism in the assembly? Not once did they ever address the situation.

"It's ridiculous that, a headteacher can stand up there, a white head teacher in front of majority people of colour, 15 year olds at the time, and say 'don't be upset that these people are racist'.

"People came out of that assembly actually crying."

In a statement sent by the schools' headteacher, Amy Cavilla, Nonsuch told South West Londoner they were investigating the alleged racist incidents at the time and the assembly, was "an attempt to re-state the school’s stance on anti racism; and ask for the students’ patience while the investigation was ongoing."

After the assembly, Sloper said students started to think how they could rebel after feeling betrayed by the school.

"Previously, most of us had felt empowered and supported."

Anise Sloper - Credit: Anise Sloper

Anise Sloper - Credit: Anise Sloper

They started to compile a dossier of all the racial incidents that had occurred at the school.

It included a white teacher referring to students of colour by their seat coordinates after saying they could not pronounce their names.

It also had the account of a black ex-student who described time in the Combined Cadet Forces (CCF) with boys school Sutton Grammar, in which she was repeatedly called the n-word by white and Asian students, and likened to a gorilla.

By Thursday 15th October, having organised the protest on WhatsApp after students were prevented from sending emails on the school system, everything was in place.

Sloper describes how roughly 20 students gave emotional speeches from a raised canteen platform to hundreds brandishing banners in the school's playground, talking into her phone connected to a Bluetooth speaker.

"Hearing my friends do their speeches, and hearing them say things that everyone resonated with and then everyone would cheer, and everyone would scream and clap.

"Nothing will ever compare. It couldn't have happened without everyone's cooperation. And we'd never pulled together like that."

After the protest, over 900 alumni of the school signed an open letter calling on it to improve its handling of race issues.

"We felt important, which is something that students don't get to feel at school. You know, it's very much you're not in charge here. And for a second we were like, well, we are!" Sloper said.

In the same month Djimon Gyan, 15, staged his own protest, though less dramatic.

A black student at Wilson's School, he wrote a piece in a local paper, partly in response to the events at Nonsuch, titled 'Sutton Schools might have a Race Problem'.

It came after Wilson's, a boys grammar school, received an open letter asking them to improve their handling of race with over 400 signatures from current and former students in summer 2020.

Wilson's School - Credit: Noel Foster

Wilson's School - Credit: Noel Foster

Though he said he is lucky to have experienced few racial incidents from teachers, he remembered one repeatedly calling him Jamal in Year 7, despite him and his friends correcting them time after time.

"I never corrected somebody that many times for them to still get my name wrong," he told South West Londoner.

He also thought the lack of diversity amongst staff is a problem in dealing with racist behaviour.

"Staff are supposed to be an outlet. And when most of the staff aren't of an ethnic minority background, it's harder to talk.

He described how when he had an ethnic minority form tutor, "you would hear more about these issues and talk to her about these issues.

"And she'll bring up her own experiences. And that makes it easier to talk."

But it's the casual 'banter' between boys, full of racist jibes, that Gyan said characterises racism between students, which he said in such a diverse school can occur between students of colour more than from white students.

"The classic is, I guess, fried chicken and stuff like that. I guess worse is stuff like gang violence and shootings and stabbings."

He continued the issue is complicated as most of the time those making the remarks are good friends, making it harder to confront them about it, such as when racially insensitive comments made by one of his friends were posted online.

"I guess that was also kind of disconcerting. And I guess for a bit I didn't talk to him but I ended up talking to him again anyway, because we sit in a lot of lessons next to each other, and it's kind of impossible to completely just ignore someone like that."

However, the ethnic diversity among students can provide solidarity.

"It's not hard to find someone who's gone through a similar thing that you can talk to about it," he said.

In the same month Djimon Gyan, 15, staged his own protest, though less dramatic.

A black student at Wilson's School, he wrote a piece in a local paper, partly in response to the events at Nonsuch, titled 'Sutton Schools might have a Race Problem'.

It came after Wilson's, a boys grammar school, received an open letter asking them to improve their handling of race with over 400 signatures from current and former students in summer 2020.

Wilson's School - Credit: Noel Foster

Wilson's School - Credit: Noel Foster

Though he said he is lucky to have experienced few racial incidents from teachers, he remembered one repeatedly calling him Jamal in Year 7, despite him and his friends correcting them time after time.

"I never corrected somebody that many times for them to still get my name wrong," he told South West Londoner.

He also thought the lack of diversity amongst staff is a problem in dealing with racist behaviour.

"Staff are supposed to be an outlet. And when most of the staff aren't of an ethnic minority background, it's harder to talk.

He described how when he had an ethnic minority form tutor, "you would hear more about these issues and talk to her about these issues.

"And she'll bring up her own experiences. And that makes it easier to talk."

But it's the casual 'banter' between boys, full of racist jibes, that Gyan said characterises racism between students, which he said in such a diverse school can occur between students of colour more than from white students.

"The classic is, I guess, fried chicken and stuff like that. I guess worse is stuff like gang violence and shootings and stabbings."

He continued the issue is complicated as most of the time those making the remarks are good friends, making it harder to confront them about it, such as when racially insensitive comments made by one of his friends were posted online.

"I guess that was also kind of disconcerting. And I guess for a bit I didn't talk to him but I ended up talking to him again anyway, because we sit in a lot of lessons next to each other, and it's kind of impossible to completely just ignore someone like that."

However, the ethnic diversity among students can provide solidarity.

"It's not hard to find someone who's gone through a similar thing that you can talk to about it," he said.

David Okoh - Credit: David Okoh

David Okoh - Credit: David Okoh

Studying medicine at Birmingham University, David Okoh, 21, also highlighted the benefits of going to a diverse school.

"I see patients of all kinds of different skin colours and races and stuff like that. And I feel like I'm able to interact and actually appreciate other people's cultures just in a consultation of 10 minutes."

But having left Wilson's in 2018, Okoh remembered always being aware of his race, including when a teacher told him and two other black friends they shouldn't walk around together because they looked 'intimidating' in Year 11.

"He was like, what I've noticed these sort of times is that you're getting a bit older, you're getting bigger, that you're walking around the school as if you have authority, like you run the place.

"We literally just left and said that is ridiculous. Three educated boys can't even walk together."

But one incident from Year 9 particularly stuck in his mind.

Migrants were discovered attached to the bottom of a coach Okoh's class was riding in after returning to school following a trip, leading a teacher to make a joke.

"'Oh, I thought David was one of them'.

"It was such an uncomfortable comment at the time and you see [another] teacher just cackling away like ha ha ha that's so funny. I think at the time I was quite visibly upset.

"That feeling of alienation is just small comments like that, and small bubbling feelings like that kind of build.

"After that I could struggle to have respect for [that teacher] to be honest."

The alienation was compounded by the schools hair policies, which at the time prevented students from getting skin fades, a standard haircut for black males, as they were deemed 'unprofessional'.

"When I get a haircut, that's like a zero, I'm not trying to be rebellious, I'm just trying to look neat and look presentable. And for them, they didn't quite understand that struggle."

"[The headteacher] asked me, how would you feel about being the only black student in your year group?"

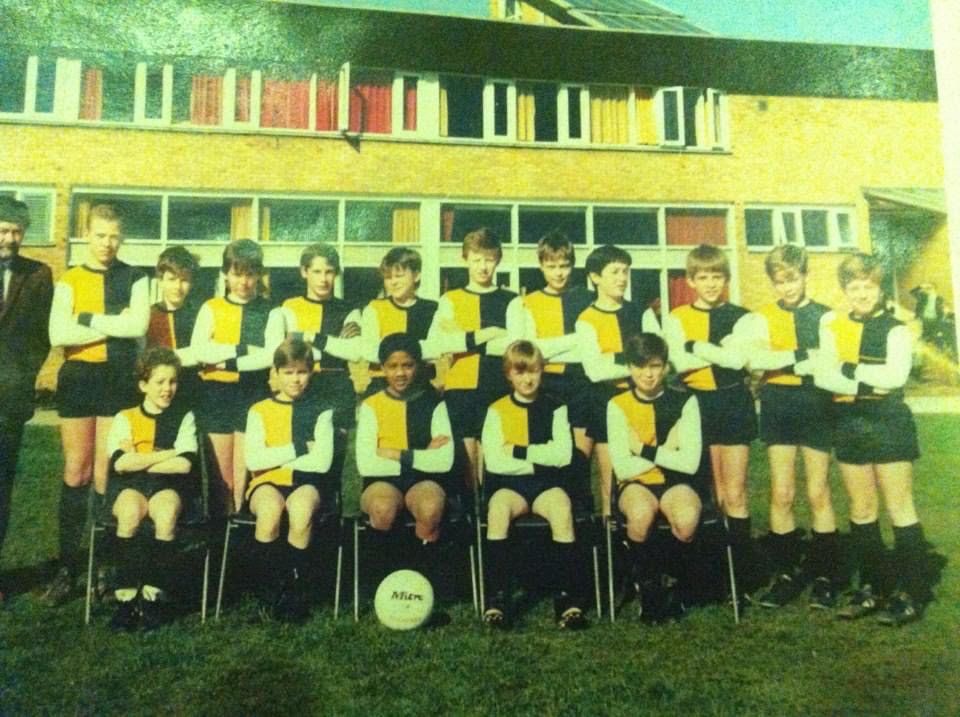

David Coomansingh, 47, said he remembered the interview with the then headteacher of Wilson's like it was "this morning".

"My answer, I still remember it now, was I wouldn't see it as anything different because I've come from a primary school where I was the only black student."

The interview went well, and he started at the school in 1986.

He emphasised he can't remember ever being treated negatively because of his race, and he cherished his time there.

Though occasionally he could stick out, such as when a word similar sounding to the n-word was read out in a Latin class.

"I still remember I felt like every set of eyes, 29 sets of eyes, were on me," he said.

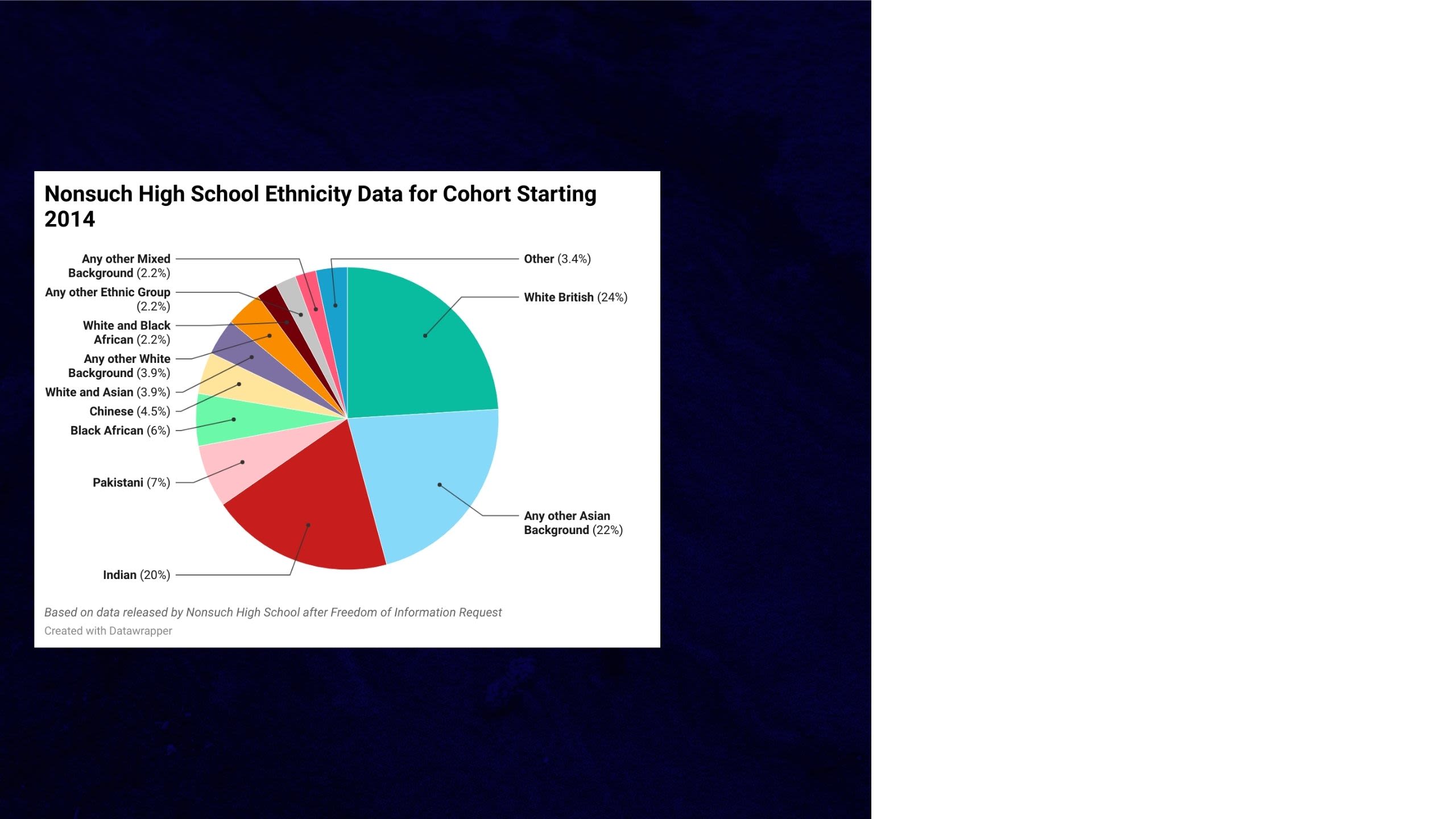

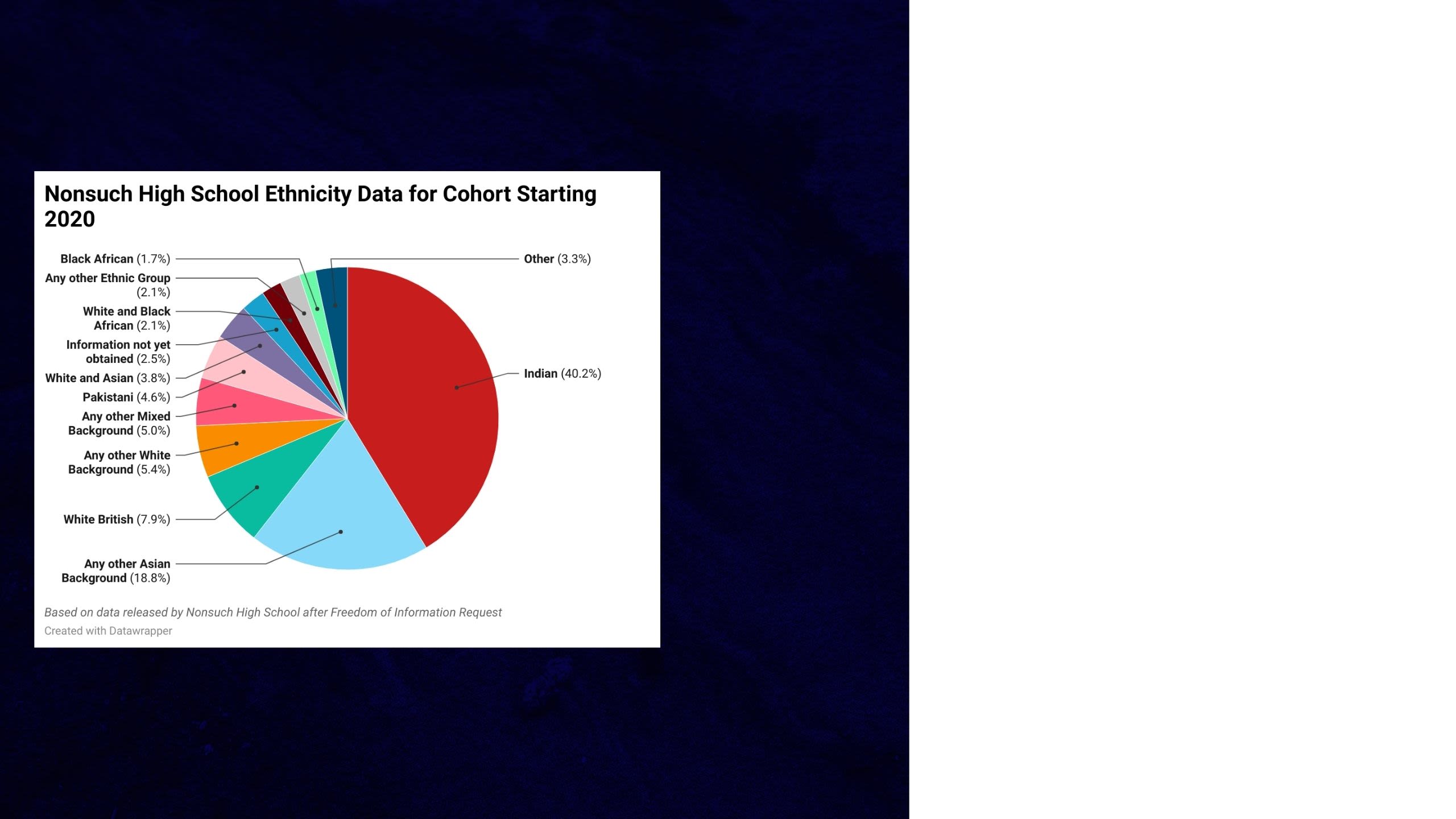

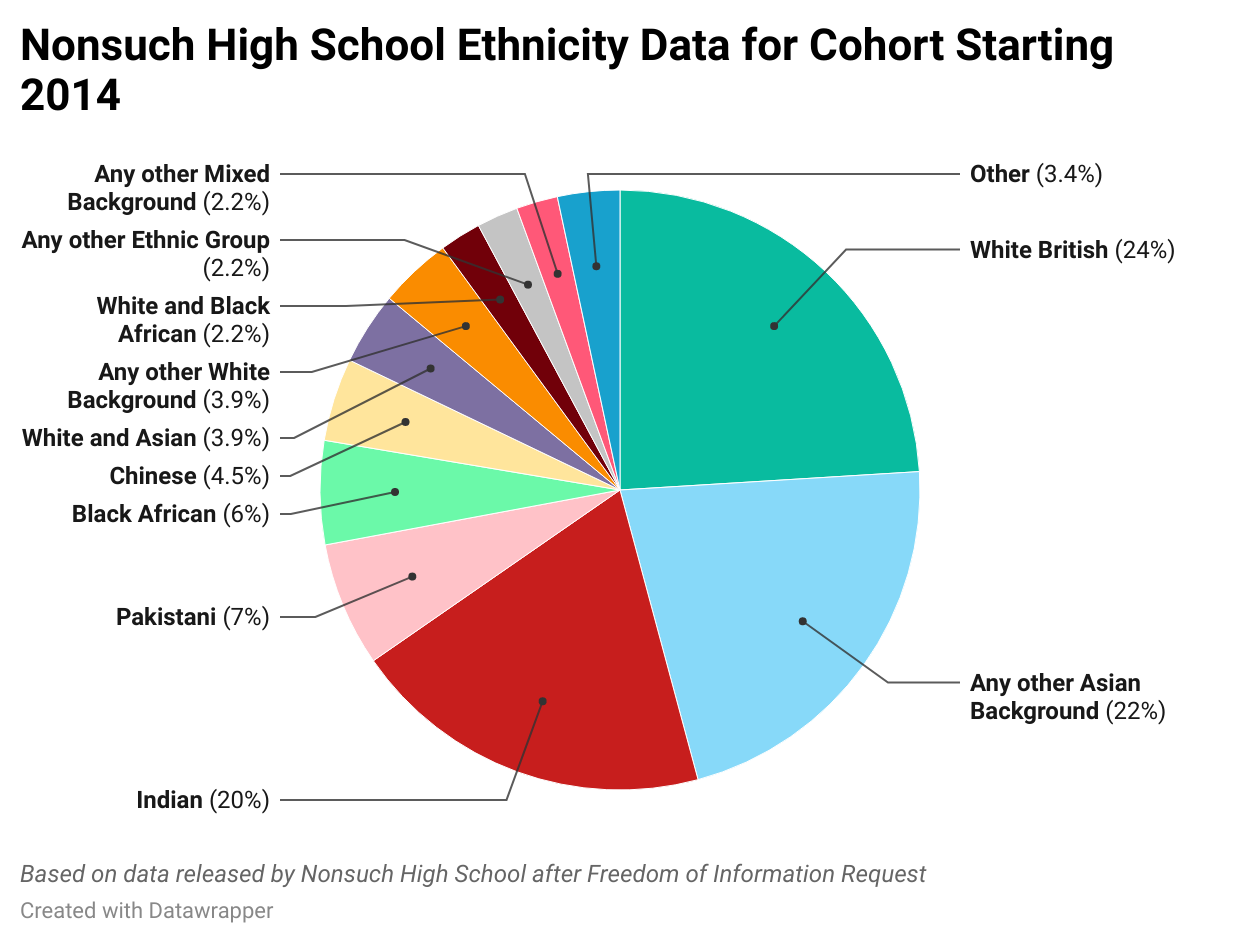

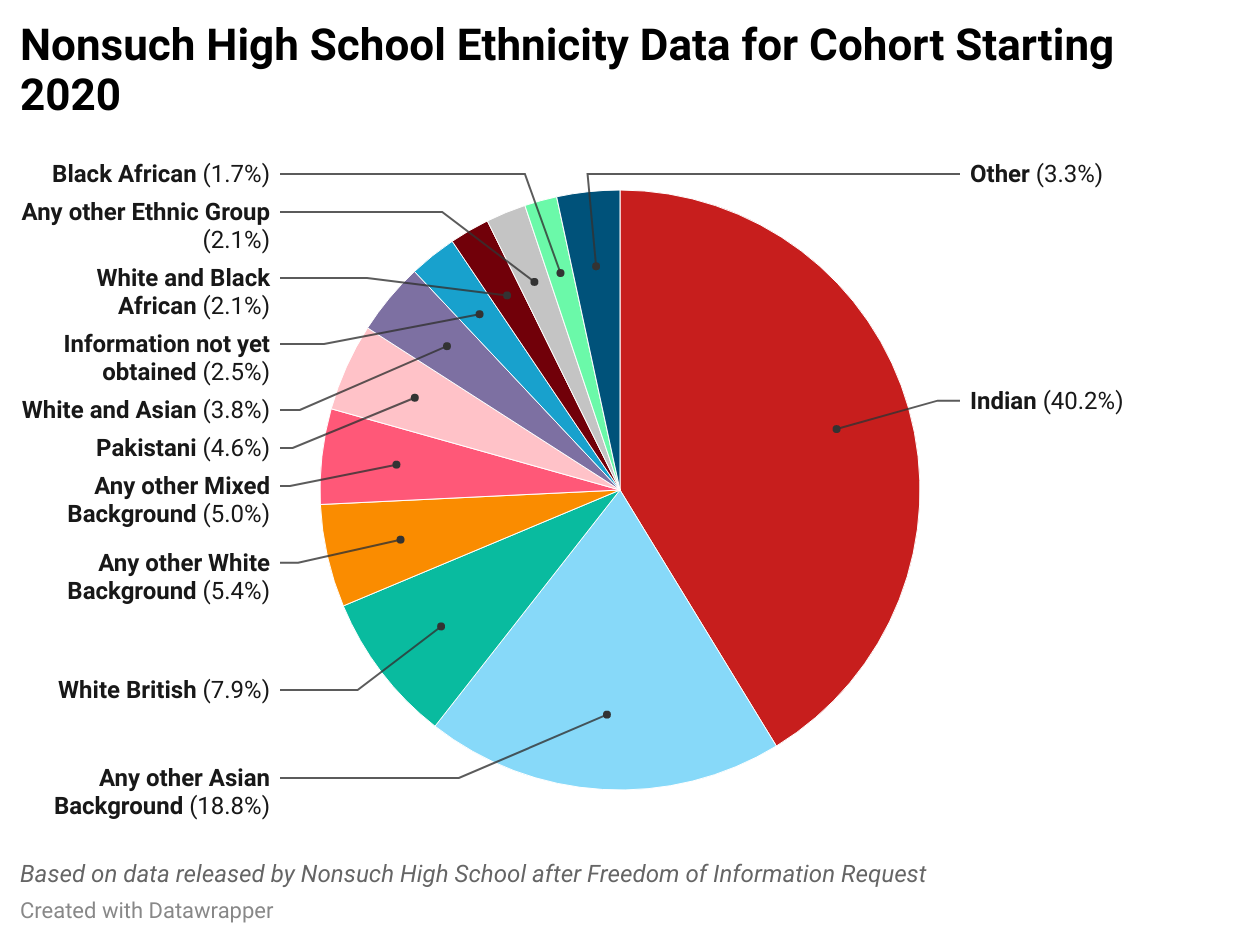

Like many London schools Wilson's has undergone a massive demographic change in the past few decades.

Numbers of ethnic minority students dramatically increased to the point they are likely the majority, though figures aren't currently available, which Coomansingh believed was partly due to selection criteria focusing more purely on academic ability.

He said he was uniquely placed to observe the trend, having lived on the same road as the school for 30 years.

"I see [students of colour] daily, you know, coming into the school. Nothing compared to anything that I would have seen back in the 80s, so a huge jump in culture."

He also pondered how students are much more politically conscious, with the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, whereas he didn't "remember picking up on anything like that at all."

"I loved history when I was a student there and it was all, unfortunately, World War Two history and the Boer War and all that type of stuff. It was never anything as exciting as 1960s civil rights movements and things like that. I imagine that may very well have changed," he said.

David Coomansingh whilst at Wilson's - Credit: David Coomansingh

David Coomansingh whilst at Wilson's - Credit: David Coomansingh

He was captain of the football team

He was captain of the football team

David Coomansingh now - Credit: David Coomansingh

David Coomansingh whilst at Wilson's - Credit: David Coomansingh

For Folawe Abraham, 29, who joined Nonsuch in 2003, it wasn't just black history that was missing, but black identity.

"I think that's the difference between us and them. The black girls who went to school then and the black girls who go to school now. They've got a voice and they will say whatever they want," she said.

Low ethnic diversity, coupled with a lack of access to social media "apart from Bebo and Myspace" meant there were few opportunities to discuss black culture or issues.

Folawe Abraham - Credit: Folawe Abraham

Folawe Abraham - Credit: Folawe Abraham

"If your life is okay, or great, you don't necessarily seek something outside because you don't even know what to seek," she continued.

Sunna Coleman, founder and editor-in-chief of lifestyle and career blog, Inspired in the City, who joined Nonsuch in 2002, highlighted that though there were few black girls, there was a moderate cohort of South and East Asian girls in her year.

"It's just a shame that I felt I had to choose a side when I was there - either you choose to try and fit into Western society and leave your blended identity at home, or you stick to those more like you and struggle to integrate.

"At the time, issues of race seemed to be reserved as a problem for minority groups, and not something that White pupils concerned themselves with - a reflection of society as a whole," she said.

Sunna Coleman - Credit: Sunna Coleman

Sunna Coleman - Credit: Sunna Coleman

Abraham puts the increase in ethnic minority pupils at Nonsuch largely down to the scrapping of the catchment area, a requirement that students live within a certain distance to the school.

Protests could never have happened in her time at Nonsuch she claimed, partly as she remembers so few racial incidents occurring, which she believes to an extent was because lower numbers of ethnic minority students made them less of a threat.

"We didn't think okay, we're going to come together because we're black because it was never a situation of us being in the same classes or in the same form so you can get to know each other.

"So I think that's also why we probably weren't seen as a threat because it was just literally silos of people."

But most important to such organisation being impossible was the absence of social media, she said.

"There could be injustice going on at Wilsons when I was in school, I wouldn't know.

"Unless someone from Wilson's was talking to maybe a Nonsuch girl. Whereas now, instantaneously, you're going to find out what's going on.

"Instantaneously - do we want to do something about it? Is everyone going to come and bring banners, come outside Wilson's at the end of school, everyone come now - that is literally less than an hour.

"It would have been impossible to do that. We didn't have the tools."

For Folawe Abraham, 29, who joined Nonsuch in 2003, it wasn't just black history that was missing, but black identity.

"I think that's the difference between us and them. The black girls who went to school then and the black girls who go to school now. They've got a voice and they will say whatever they want," she said.

Low ethnic diversity, coupled with a lack of access to social media "apart from Bebo and Myspace" meant there were few opportunities to discuss black culture or issues.

Folawe Abraham - Credit: Folawe Abraham

Folawe Abraham - Credit: Folawe Abraham

"If your life is okay, or great, you don't necessarily seek something outside because you don't even know what to seek," she continued.

Sunna Coleman, founder and editor-in-chief of lifestyle and career blog, Inspired in the City, who joined Nonsuch in 2002, highlighted that though there were few black girls, there was a moderate cohort of South and East Asian girls in her year.

"It's just a shame that I felt I had to choose a side when I was there - either you choose to try and fit into Western society and leave your blended identity at home, or you stick to those more like you and struggle to integrate.

"At the time, issues of race seemed to be reserved as a problem for minority groups, and not something that White pupils concerned themselves with - a reflection of society as a whole," she said.

Sunna Coleman - Credit: Sunna Coleman

Sunna Coleman - Credit: Sunna Coleman

Abraham puts the increase in ethnic minority pupils at Nonsuch largely down to the scrapping of the catchment area, a requirement that students live within a certain distance to the school.

Protests could never have happened in her time at Nonsuch she claimed, partly as she remembers so few racial incidents occurring, which she believes to an extent was because lower numbers of ethnic minority students made them less of a threat.

"We didn't think okay, we're going to come together because we're black because it was never a situation of us being in the same classes or in the same form so you can get to know each other.

"So I think that's also why we probably weren't seen as a threat because it was just literally silos of people."

But most important to such organisation being impossible was the absence of social media, she said.

"There could be injustice going on at Wilsons when I was in school, I wouldn't know.

"Unless someone from Wilson's was talking to maybe a Nonsuch girl. Whereas now, instantaneously, you're going to find out what's going on.

"Instantaneously - do we want to do something about it? Is everyone going to come and bring banners, come outside Wilson's at the end of school, everyone come now - that is literally less than an hour.

"It would have been impossible to do that. We didn't have the tools."

Promise

The Nonsuch protests were perhaps the ultimate expression of something normally punished at school: talking back.

Sloper admitted: "It wouldn't have been uncalled for for them to stick us all in isolation.

"Would have been wrong, but I've seen schools do it."

But instead, the school began to talk to students.

Sloper remembered after the protests some of the few teachers of colour at the school held a drop-in session where they shared their own experiences, as well as listening to those of students.

"They provided the first open space with teachers that we could really, like, communicate in. And it was amazing. It was really cool."

Whilst continuing those sessions, the school also began anti-racism teacher training.

Sloper remembers how her form tutor would periodically tell her class what the training was like.

"If she thought it was rubbish, she would have told us but I think she came out of it feeling that it was like productive time and that they really learned something."

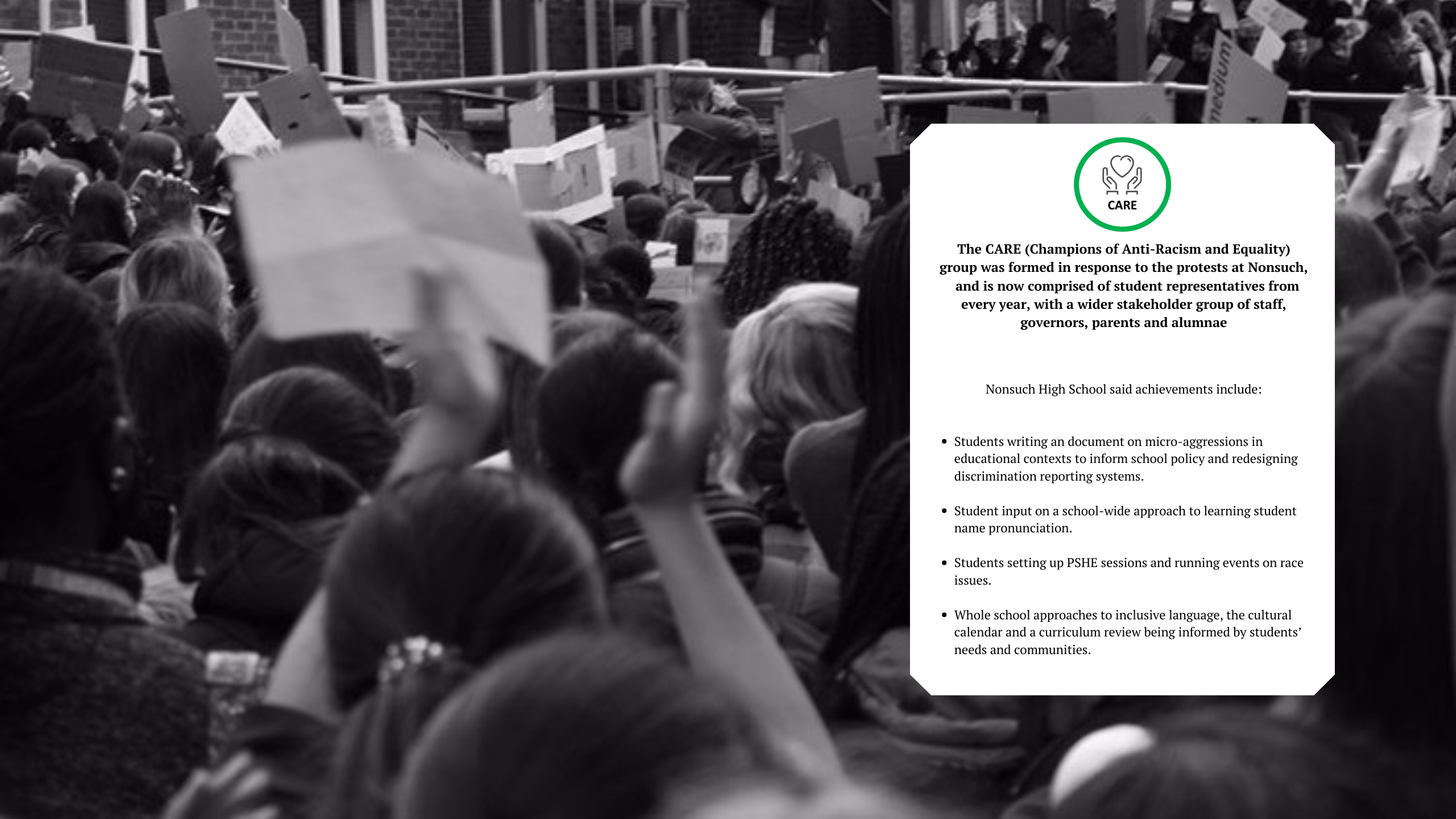

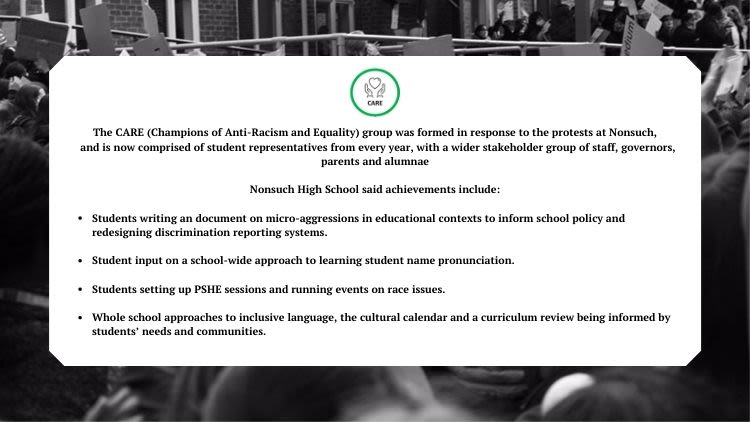

Nonsuch also developed the CARE (Champions of Anti-Racism and Equality) council, a forum for student representatives across year groups to have input in how the school approaches race issues.

In a comment to South West Londoner, Nonsuch High School said: "Schools and institutions re-examined their work to combat racism following the murder of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter movement gaining global momentum. Nonsuch, like many other schools in south west London in rapidly diversifying communities, was no exception.

"The school prides itself on empowering young women and advancing equality so the strength of student feeling expressed in October 2020 was certainly powerful. The school’s antiracism strategy was given fresh impetus and its work accelerated. Staff and students alike have benefitted from a focus on allyship and empathy as we all move forwards. Our website provides a view of the journey we are on.

"It is not performative, it is transformative – and as with all transformations, different strands happen at different speeds. 2022 is the year of embedding and sustaining the work of the previous 18 months. We are reviewing our curriculum thematically through the human rights convention, inclusivity and representation."

For Sloper, who left the school after GCSEs in summer 2021, what she saw from the school looked like genuine effort.

"I feel like they tried. But it's a long, complicated problem, that can only be fixed over years, because it's systemic.

Eventually, there won't be an all white teaching body at Nonsuch, but they can't fire all their white teachers. It will only get fixed when the staff reflect the students."

The Nonsuch protests were perhaps the ultimate expression of something normally punished at school: talking back.

Sloper admitted: "It wouldn't have been uncalled for for them to stick us all in isolation.

"Would have been wrong, but I've seen schools do it."

But instead, the school began to talk to students.

Sloper remembered after the protests some of the few teachers of colour at the school held a drop-in session where they shared their own experiences, as well as listening to those of students.

"They provided the first open space with teachers that we could really, like, communicate in. And it was amazing. It was really cool."

Whilst continuing those sessions, the school also began anti-racism teacher training.

Sloper remembers how her form tutor would periodically tell her class what the training was like.

"If she thought it was rubbish, she would have told us but I think she came out of it feeling that it was like productive time and that they really learned something."

Nonsuch also developed the CARE (Champions of Anti-Racism and Equality) council, a forum for student representatives across year groups to have input in how the school approaches race issues.

In a comment to South West Londoner, Nonsuch High School said: "Schools and institutions re-examined their work to combat racism following the murder of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter movement gaining global momentum. Nonsuch, like many other schools in south west London in rapidly diversifying communities, was no exception.

"The school prides itself on empowering young women and advancing equality so the strength of student feeling expressed in October 2020 was certainly powerful. The school’s antiracism strategy was given fresh impetus and its work accelerated. Staff and students alike have benefitted from a focus on allyship and empathy as we all move forwards. Our website provides a view of the journey we are on.

"It is not performative, it is transformative – and as with all transformations, different strands happen at different speeds. 2022 is the year of embedding and sustaining the work of the previous 18 months. We are reviewing our curriculum thematically through the human rights convention, inclusivity and representation."

For Sloper, who left the school after GCSEs in summer 2021, what she saw from the school looked like genuine effort.

"I feel like they tried. But it's a long, complicated problem, that can only be fixed over years, because it's systemic.

Eventually, there won't be an all white teaching body at Nonsuch, but they can't fire all their white teachers. It will only get fixed when the staff reflect the students."

Conversation was also key to Gyan feeling supported by Wilson's soon after his piece was published.

Coming into school he was "shocked" to be notified a senior teacher wanted to talk to him.

"But it was fine because what he wanted to talk to me about was what exactly the school could do to combat stuff like that," he said.

Both Gyan and Okoh remembered another senior teacher being particularly willing to hear them out on their concerns.

For Okoh, his opposition to the school's hair policies culminated in a conversation with the teacher, where he said they both produced a scrapbook of haircuts on black and white males to discuss what was 'professional'.

"He was actually understanding and he was like, yeah, actually, it doesn't really make too much sense the whole rules."

Wilson's confirmed that hair policies are now more progressive.

Okoh felt students have their voices heard more since he left the school in the wake of Black Lives Matter, with Gyan also confirming he felt things have improved since.

But the top down hierarchy of school can still sometimes make students afraid to speak out on how things can get better, Gyan believed

"I think that we are more scared of some of our teachers than other Sutton schools."

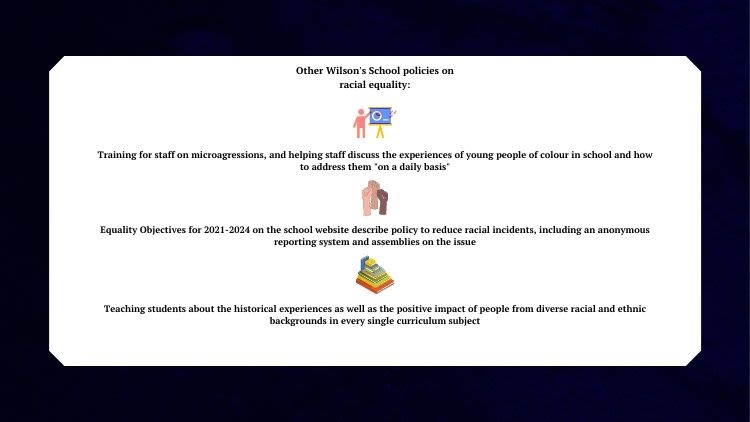

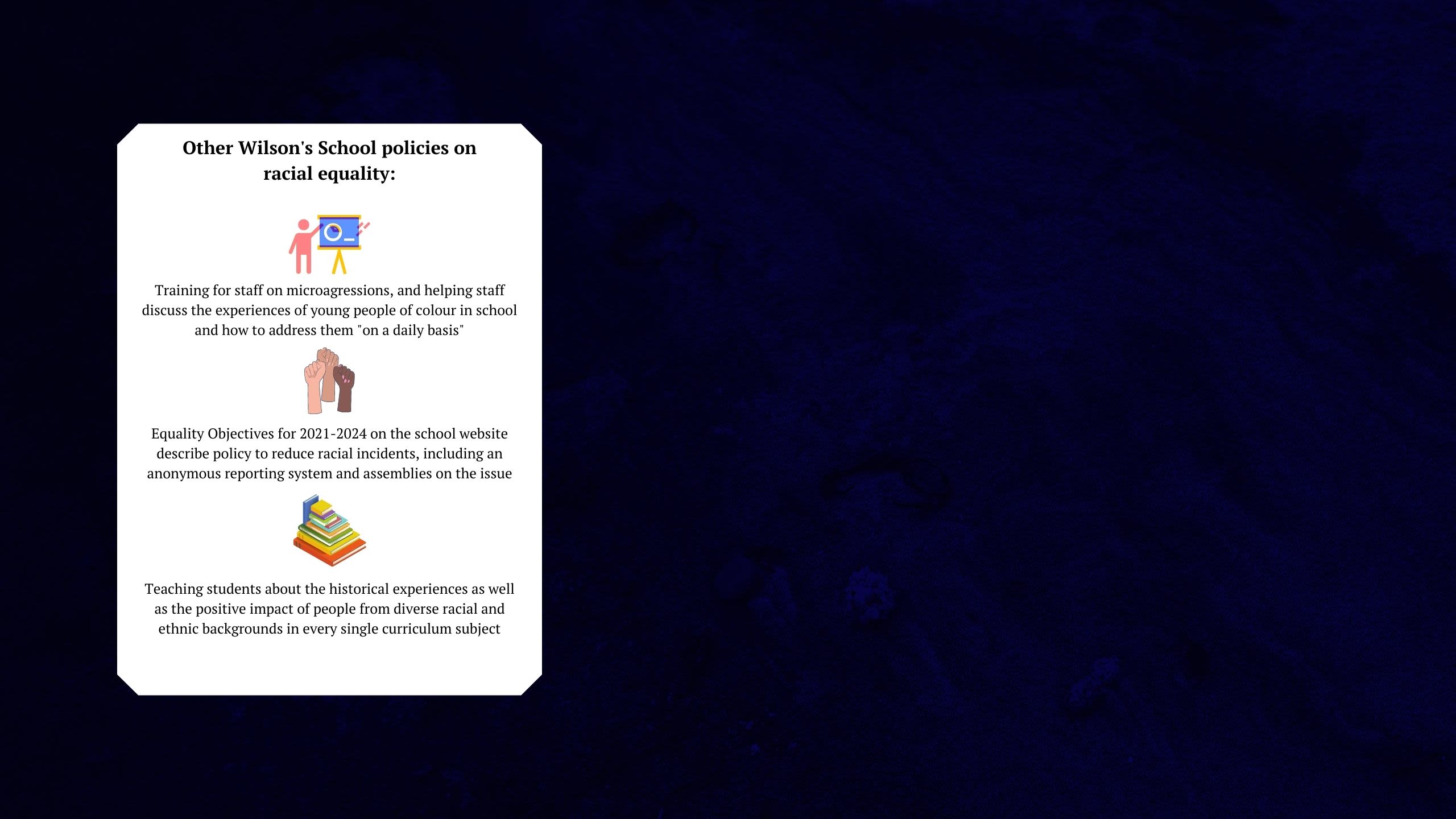

Wilson's School told South West Londoner that they implemented a Diversity Prefect and Diversity Team made up of students in the past few years, and appointed a teacher as Equalities Lead.

They added one of the things she will focus on this term is "strategy to ensure that the school is as welcoming and inclusive as it can possibly be for all current and prospective pupils and members of staff regardless of race or cultural background.

"Together with the Head, she will be looking at all communications and materials promoting the school to prospective pupils and members of staff.

"She will also continue the student voice exercises that she has been conducting over the past two years with current pupils in the school, which several other members of staff have also been involved with."

A power shift from teachers to students on race issues could make a contrast from what Okoh described as the "powerlessness" of being a young student at school and thinking "there's not really much I can do, this is just the system, it's part and parcel for us."

As protest spreads, the hope is that progress will too.

Conversation was also key to Gyan feeling supported by Wilson's soon after his piece was published.

Coming into school he was "shocked" to be notified a senior teacher wanted to talk to him.

"But it was fine because what he wanted to talk to me about was what exactly the school could do to combat stuff like that," he said.

Both Gyan and Okoh remembered another senior teacher being particularly willing to hear them out on their concerns.

For Okoh, his opposition to the school's hair policies culminated in a conversation with the teacher, where he said they both produced a scrapbook of haircuts on black and white males to discuss what was 'professional'.

"He was actually understanding and he was like, yeah, actually, it doesn't really make too much sense the whole rules."

Wilson's confirmed that hair policies are now more progressive.

Okoh felt students have their voices heard more since he left the school in the wake of Black Lives Matter, with Gyan also confirming he felt things have improved since.

But the top down hierarchy of school can still sometimes make students afraid to speak out on how things can get better, Gyan believed

"I think that we are more scared of some of our teachers than other Sutton schools."

Wilson's School told South West Londoner that they implemented a Diversity Prefect and Diversity Team made up of students in the past few years, and appointed a teacher as Equalities Lead.

They added one of the things she will focus on this term is "strategy to ensure that the school is as welcoming and inclusive as it can possibly be for all current and prospective pupils and members of staff regardless of race or cultural background.

"Together with the Head, she will be looking at all communications and materials promoting the school to prospective pupils and members of staff.

"She will also continue the student voice exercises that she has been conducting over the past two years with current pupils in the school, which several other members of staff have also been involved with."

A power shift from teachers to students on race issues could make a contrast from what Okoh described as the "powerlessness" of being a young student at school and thinking "there's not really much I can do, this is just the system, it's part and parcel for us."

As protest spreads, the hope is that progress will too.