Put through the wringer

Boxing and the west London community

It must have been a haunting sight. On Sunday 5 June, a World Boxing Federation All Africa lightweight bout in Durban had to be stopped after one of the boxers, Simiso Buthelezi, began shadow boxing an invisible opponent.

The contest stopped by the referee, Buthelezi was then taken to hospital, where he was placed in an induced coma after it was discovered he had bleeding on the brain

A couple of days later, the 24-year-old passed away. According to Reuters, trainer Bheki Mngomezulu was reported as saying Buthelezi was in “perfect health in the lead-up to the bout”.

Though this event did not spark a widespread media debate about the dangers of boxing, it provided stark testimony to the fact that they exist.

Very scary in South Africa please 🙏🏼 for Simiso Buthelezi (4-1). At 2:43 of the 10th & final round, Siphesihle Mntungwa (7-1-2) falls through the ropes but then Buthelezi appears to lose his understanding of the present situation. Mntungwa takes the WBF African lightweight title pic.twitter.com/YhfCI623LB

— Tim Boxeo (@TimBoxeo) June 5, 2022

A brief history lesson

Rules and respectability

Muybridge, Eadweard, 1830-1904, artist, "The zoopraxiscope* – Athletes – Boxing (No. 2, title from item.)" (1893). Credit: Wikimedia Commons

A keen gentleman boxer. Phillips, Thomas, Portrait of Lord Byron, British poet (1788-1824) (1813). Credit: Wikimedia Commons

A keen gentleman boxer. Phillips, Thomas, Portrait of Lord Byron, British poet (1788-1824) (1813). Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Boxing card, c.1925. Unknown author. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Boxing card, c.1925. Unknown author. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Geoff Charles, A boxing school established in Llanarmon by W G Buchanan, an ex-air force boxing champion, and the Rev T D Williams. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Geoff Charles, A boxing school established in Llanarmon by W G Buchanan, an ex-air force boxing champion, and the Rev T D Williams. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

The rules for boxing that are still used today were first codified in the 1860s, and this represented an enormous step in improving safety standards on the bareknuckle brawls of before.

A crucial difference between the new Queensberry Rules, and their antecedent London Prize Ring Rules, was the requirement to wear gloves.

Though named after the ninth marquess of Queensberry, famed in history for being the initial defendant in Oscar Wilde's ill-fated libel suit, the nobleman was not much of a boxer.

The rules were drawn up by Welsh sportsman, Cambridge-educated John Graham Chambers of the Amateur Athletic Club, who sought an aristocrat's patronage to lend the sport a greater air of respectability.

Though shunned by those who considered them unmanly, the influx of young boxers such as Jem Mace who preferred the new rules helped to grow their popularity. Testament to this is the fact that the last heavyweight championship bout under the old prize ring rules took place in 1889.

Yet it still struggled to gain the widespread respectability amongst the upper and middle classes that sports such as cricket and football had, in part due to an evangelical revival which hardened attitudes to certain pastimes.

With associations of crowd disorder, drinking, gambling and violence in and out of the ring, boxing was increasingly seen as sinful, though it was taught in state and private school P.E. lessons for much of the twentieth century.

This came to an end in the sixties. Contrary to popular belief, boxing was not banned despite the best efforts of physician and MP Edith Summerskill, whose proposed Boxing Bill did not make it beyond the preliminary debate, held on 21 December 1960.

However, though unsuccessful in the voting lobbies, Summerskill had captured something of the zeitgeist. Her arguments, based on the arguable premise that the aim of boxing is "to render one's opponent insensible" tapped into a wider movement outside of parliament.

Increasingly boxing came to be seen, along with national service, as a remnant of a more violent past, and was phased out of mainstream teaching.

Somewhere to call home

A trip to West London Boxing Academy

Tucked away on an industrial estate in the otherwise leafy suburb of Hanwell is West London Boxing Academy, a club for whom community is something of a raison d'être.

There I meet Joe Theobald, 24, a sports science graduate from Loughborough University who is now a full-time boxing coach.

Once an amateur boxer himself, Joe is committed to teaching the art of boxing and the life lessons that come with it.

"Boxing’s one of the hardest sports in the world. It’s a mixture of speed, power, coordination, balance, timing.

"And mentally you’ve got to be bulletproof. Think under fire and play the chess game."

More to it than a scrap then? He fires back immediately.

"It's not Rock'Em Sock'Em Robots."

There's two sides to boxing training, the work that goes on outside the ring, which includes running (called 'roadwork'), skipping, working the heavy bag and other forms of cardio, and sparring.

Sparring is the closest form of preparation to a fight and Joe says for a gym to be worth it's salt, it must be well policed.

Most of what's done is technical sparring, which works specific aspects of a boxer's game, and if the temperature rises, rare though I'm told it is, Joe has no problem stepping in.

"I'll stop a spar in a heartbeat. If it gets heavy, I'll tell them to go and punch the heavy bag till you're exhausted and then come back in the ring."

Not all boxing clubs offer sparring, but Joe's frank about West London Boxing Academy's ambitions.

“We don’t want to be just a run-of-the-mill boxing club.

"We want to find the next superstar, and you’re not going to find that in Richmond-upon-Thames.”

Such is the thinking behind the proposed community boxing club that West London's looking to open on the Havelock Estate.

There are a few people living on the estate who already train at West London, but Joe believes this new satellite will help discover yet more untapped potential, the "rough diamonds" as he calls them.

It's an estate which doesn't have access to much by way of sports facilities, as I'm told there are three primary schools with one playground between them in the area.

There are further social problems with drugs and gangs, which youngsters at a loose end can sometimes get caught up in.

"There’s a lot of drugs over at Havelock and a lot of kids end up being runners."

And so the idea is to give them a passion, since boxing is a sport that requires commitment and discipline and, contrary to the professional image, for those starting out it doesn't help to have an oversized ego.

Yet Joe also argues that for kids who come from unsettled backgrounds, boxing can be a means of building themselves up.

"Some kids have spent most of their life being told their not good enough.

"But they then get a chance to feel like they’re actually achieving something, and probably the only time they get a well done during the week is when they come down here."

It's a safe space to learn some of life's more difficult lessons such as the value of hard work and how to deal with losing.

Another benefit sparring especially teaches is how to keep your cool, which Joe points out is invaluable for teenagers going through public exams.

Though West London is looking to join the Sport England-endorsed Better Health campaign, which aims to improve the nation's health across the board, there is an undoubted sense of its own mission.

I'm just about to leave when Joe mentions the club is due a visit from a couple of members of staff at Ealing Alternative Provision, who are looking to partner up with West London Boxing Academy.

It's a school to which pupils in the area are referred if they struggle to learn in a mainstream environment, whether that be because of behavioural difficulties or special educational needs.

Just as he finishes speaking, Kelly Waterton, head of teaching and learning, and teacher Caroline O'Connor walk on to the skipping rope-strewn floor mats.

Keen not to catch them off guard, Joe tentatively asks if they would be willing to put to me in their own words what they hope to achieve by working with West London.

They agree. And with that Joe shows off the club's facilities which they seem duly impressed by.

Passing gloves signed by Frank Bruno, Ray Jones Jr. and a host of other famous visitors to Hanwell on their way up the stairs, Caroline and Kelly join me on the balcony.

With little hesitation, Caroline tells me how Ealing Alternative Provision is hoping to enrich the curriculum it offers its pupils.

She says: "We want to offer them something during the school day that’s good for their health and fitness."

Almost as importantly however, and as though singing from Joe's hymn sheet, she adds the club can "give pupils somewhere to go without going straight home".

It's an opportunity the two teachers seem keen to take. As Caroline points out, "there aren’t many of these places around".

It's a major step in the direction this club is looking to head in, which will be really set in motion when the community satellite opens in a few months.

As I leave, I notice Joe is upbeat. He assures me this is because he's enjoyed the interview.

It's as though articulating the club's philosophy as a boxing gym and a business has invigorated him.

Indeed so swept up in positivity is he that he jumps up from his chair and offers me a lesson. Perhaps an opportunity to get in the ring myself?

I accept, but I suggest he keeps looking to find the next boxing superstar.

Under the arches

Adam Latreche. Credit: Lewis Harries

Adam Latreche. Credit: Lewis Harries

Working the ropes. Credit: Lewis Harries

Working the ropes. Credit: Lewis Harries

In the swing. Credit: Lewis Harries

In the swing. Credit: Lewis Harries

Observing the warm-up at Legends Boxing Gym reminds me of a session I once saw taken by PTIs at Britannia Royal Naval College.

Sweat drips off people kicking themselves into gear and woe betide anyone who expects poor form to go unnoticed.

But these early birds have chosen to set their alarms for a time that most civilians would consider ungodly, particularly at weekends.

They keep coming though and have even formed a tight-knit community themselves, much to the delight of their gregarious, if exacting, coach.

Meet the coach

It wasn't so much choice as family tradition.

Harvey Morgan, now 50, was five years old when he was taught basic boxing by his granddad.

Over coffee overlooking the green, he tells me about Jack Morgan, nicknamed 'Cakey' after his grandsons' favourite treat, who not only engrained good technique in the boys, but also gave them a sense of the tougher side of life.

This was only too natural for Jack, who had spent much of his working on Brentford docks, at times making just enough to feed his family.

It was as though he knew it would prepare Harvey well for secondary school.

“I needed to handle 5 or 6 kids at school. Teachers couldn’t solve the bullying and my granddad said this was the only way you can do it, show them that if you’re going to pick on me, you’re going to have a hard time.”

So aged 12 Harvey turned up at his first boxing club, where he remained for two years before going to Old Actonians.

There he honed his craft, he tells me, winning medals and trophies and training with an intensity that impressed his coach, Ernie.

But it was never lost on him why he was there, as he illustrated with the following anecdote.

For context, the boy who Harvey talks about confronting here had apparently made a habit of picking on him and his brother, which resulted in an earlier contretemps at a party.

It was this final showdown with the bully that heralded the end of Harvey's junior boxing career. Having made his point to the tough kids at school, he felt he no longer needed it.

He recalls Ernie's dismay at his decision to quit, underlined by the coach's explicit refusal to release his boxing card, preventing him from boxing anywhere else.

“I said, 'you can keep your card, Ern, I don’t want it. I’m done. See you later.' With that, I walked out and never boxed again."

Team sports such as football beckoned and he's so nonchalant about his early retirement that it's impossible to imagine he had any regrets in doing so.

So what brought him back to the sport via legends then?

We start heading back to the gym.

He explains how his son, called Jack after his great-grandad and who is now 27, wanted to take it up as a child, being one of those boys who "wanted to get in amongst it".

"Jack was the path that took me back to the gym."

The first gym his son trained in however was a damp and mouldy affair, to the extent that some of the kids got coughs that lasted well beyond the sessions.

Harvey therefore decided to use his building skills to produce something better.

He found it under the arches of Kew Bridge and realised it was meant to be.

Eventually though, after 19 fights and with 17 victories under his belt, Jack quit for much the same reason as his dad, namely the allure of a team game.

Yet Harvey continued with Legends and remains as steadfast in his coach's ethic as ever.

"Give me the week and I'll make them stronger."

Like Joe at West London, he feels boxing can teach valuable life lessons, which he distils down to five pillars: discipline, strength, loyalty, courage and determination.

It's for this reason that he believes boxing should be in all schools. Not sparring, after all that doesn't happen here, but all the aspects of training.

It's boxing he credits with helping develop his rather-die-than-quit attitude to life, and he's philosophical about the benefits of exercise more generally.

By this he means the mood-enhancing effects of exercise, which he believes can only ripple out from the nucleus who attend his sessions like a wave of positive energy to those around them.

With that, we arrive back at the entrance. With a friendly smile he greets the mid-morning cohort and says goodbye.

I thank him and wish the new volunteers luck, silently hoping they've followed his advice on training and hangovers.

Up-and-coming

An interview with Adam Latreche

While Harvey puts the willing through their paces, I speak to welterweight amateur boxer Adam Latreche, 21.

He's been boxing since he was 11. As he tells me, I admit to being struck by how undimmed his enthusiasm is.

He wears a smile on his face that you may more readily associate with a keen novice, but he's trained with some intensity at Legends for five years and he's game for more.

“I’m good at the sport and I know I can go the whole way. I know I can win titles.”

The Olympics is unfortunately out of the picture, however, due to the untimely nature of the four-year cycle.

Instead he is looking to work his way up the rankings, sooner rather than later.

As I speak to him, he is training for the Lonsdale Box Cup in Glasgow on 24 June.

When asked how he got into the sport, Adam replies that he was always naturally inclined towards combat sports.

But rugby, judo and MMA eventually fell by the wayside, as he committed himself more and more to boxing.

About his chosen sport, the "sweet science", he is understandably passionate.

"There's so much more to it than two guys punching," he assures me.

As if to reinforce that point, he likens it to dancing, emphasising co-ordination over brute force.

And, to be clear, there's no doubt about his looking forward to making it his life for the foreseeable.

Like everyone I've spoken to, Adam has a clear sense in his mind of boxing's positive influence on the community.

It's something he sees through coaching, which he took up as he was studying sports science at college.

Indeed, it's how we come to wrap up the interview, as several children almost as animated as their coach join him in the wringer under the arches.

The debate

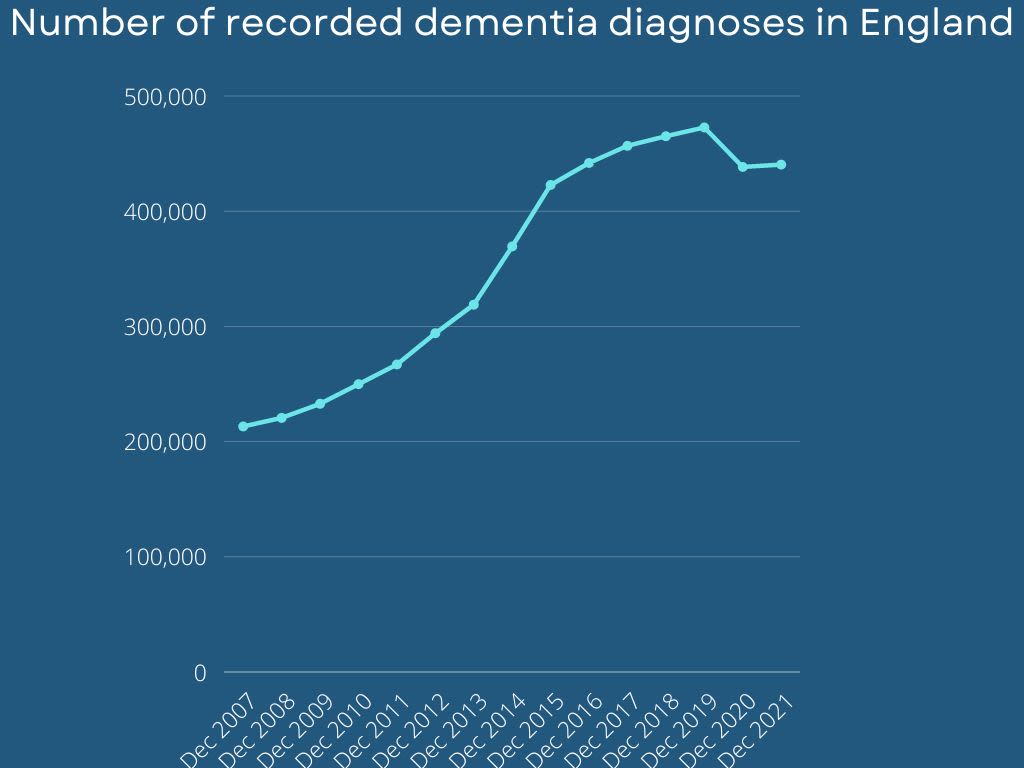

Source: Alzheimer's Research UK/NHS

Source: Alzheimer's Research UK/NHS

Published in December 2021, a study conducted by scientists at Cardiff University found a link between amateur boxing and early onset dementia.

The study found that men who boxed in their youth were twice as likely to develop Alzheimer's-symptoms as those who had not boxed.

The sport was also "linked" to the earlier onset of dementia by about five years.

Whilst not looking to comment on the exact levels of risk, it suggests it's not one that's entirely unique to boxing, as also implied by the society's call for a review of safety measures in these more mainstream sports.

Jack Charlton lived with dementia before his death in July 2020 and was famed for his ability in the air, causing many to draw a casual link between heading the ball and the degenerative condition.

Indeed the disease has been such a plague on the '66 team that hat-trick-scoring Sir Geoff Hurst has called for a ban on children heading the ball.

The gloves of one of boxing's towering figures. Also a Parkinson's sufferer in later years - linked to multiple head trauma. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

The gloves of one of boxing's towering figures. Also a Parkinson's sufferer in later years - linked to multiple head trauma. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

While no respectable medical professional would argue against the considerable health benefits of aerobic exercise, it's fair to say that recently certain sports have come under increasing scrutiny, especially those where contact with the head is inevitable.

Boxing regularly finds itself highest on the mental health agenda, likely due to its mix of direct head shots with a seemingly inherent brutality.

Cardiff University main building. Credit Stan Zurek

Cardiff University main building. Credit Stan Zurek

The study was based on a sample of 2,500 men who were aged between 45 and 59 years old when they signed up for the study in 1979.

Based on it findings, lead author Professor Peter Elwood said banning head shots would be an advisable preventative measure, presenting it as a logical extension of previous safety-orientated interventions.

These include shortening bouts, as defined in the 1860s by the Queesnberry Rules, and the mandatory use of headguards.

However, another study conducted by the Alzheimer's Society together with Glasgow University established a link between playing such sports as football and rugby and developing CTE, a disease similar to Alzheimer's and commonly known as 'punch drunk'.

Jack Charlton (1970). Credit: Panini

Jack Charlton (1970). Credit: Panini

Yet there are some who argue that seeking to totally mitigate against any risk sport may have would go some way to killing an essential aspect of its enjoyment.

This is, after all, the reason why Jack Charlton's widow, Pat, holds no grudge against the beautiful game according to The Sun, since it was ultimately such a source of pleasure for her late husband.

What should be dismissed, however, is the lazy stereotype that characterises boxing as a domain only for the morally degenerate.