Remembering the Capitol Building protest of 1965

Interview with Civil Rights veteran Jim Kates

On 6th January 2021, the world watched in horror as Washington’s Capitol Building came under attack from thousands of Trump supporters who sought to overthrow the election of Democratic President-elect Joe Biden.

This harrowing assault on the heart of democracy will forever be seared into the memory of Americans and spectators across the world.

From his home in New Hampshire, civil rights veteran Jim Kates watched the events unfold. “I kept watching between Fox and CNN”, he said. “Fox was actually the first to use the language of outrage, riot and insurrection.”

It was The New Yorker who later summed up best the day’s events for Jim. “They called it a ‘race riot’”, he said, “which, when you think about it, is exactly what it was.”

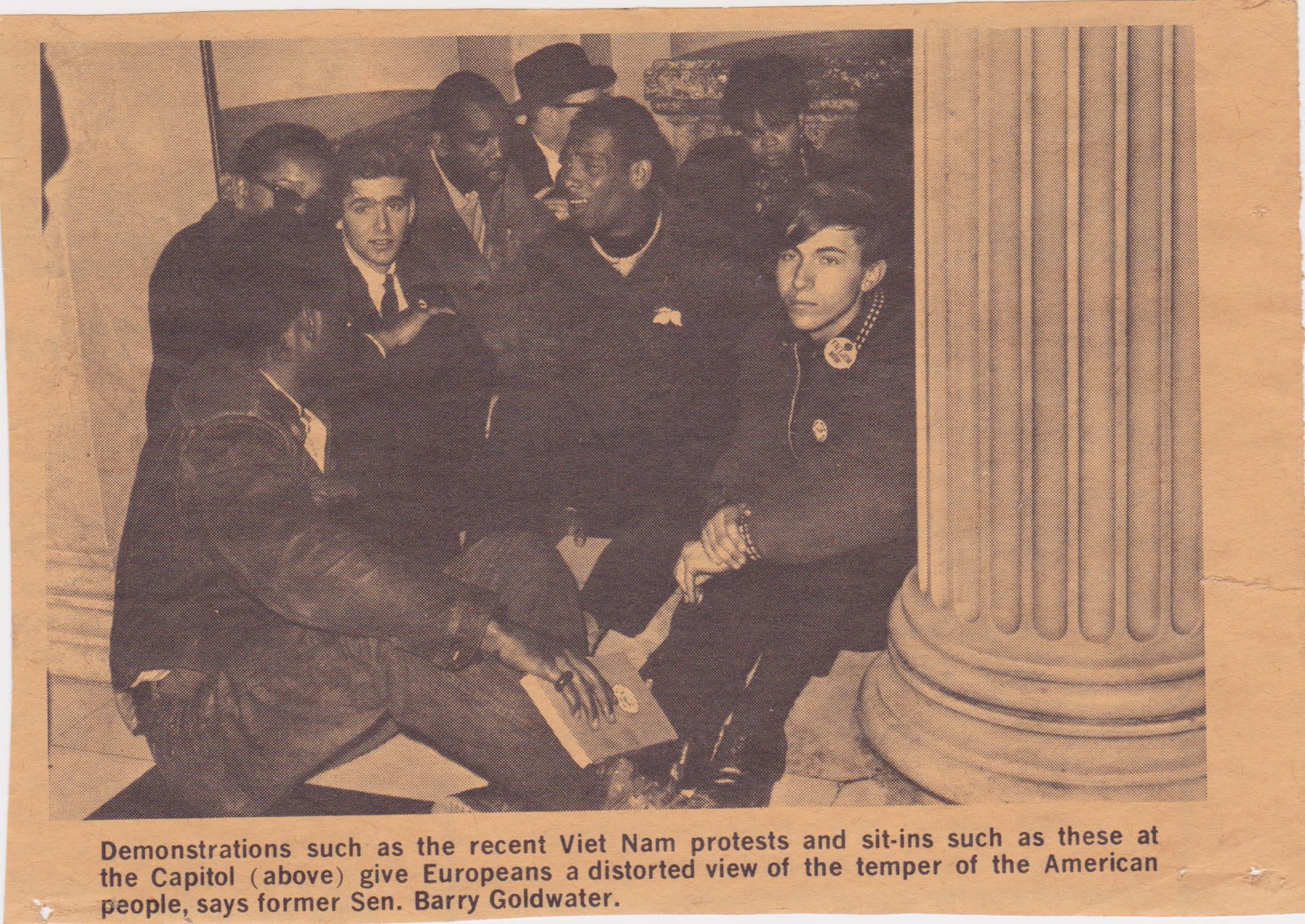

The scenes took Jim back to the Spring of 1965 when he demonstrated in the very same building alongside the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). They were calling for the passage of the Voting Rights Act following the heroic efforts of the activists during Selma’s Bloody Sunday battle.

“Instead of going to Alabama, I went to Washington D.C.”, Jim remembered. He and ten other activists went to the Capitol Building on March 15th, 1965, to demand an audience with House of Representative Speaker John McCormack, to discuss passage of a comprehensive voting rights bill.

“We wanted a confrontation with him to ask what he was going to do about the Selma crisis", Jim stated. But after hours of waiting, Senator McCormack refused to speak with the protestors.

By the afternoon, Capitol Police informed the activists that President Johnson would be arriving later that evening to give a speech to the joint Houses of Congress. “That changed the whole security system”, Jim recalled. “Remember this was only still soon after Kennedy’s assassination.”

At five o’clock Capitol Police came and removed the protestors and carried them down the steps of the Capitol, making their racial prejudices abundantly clear.

As a white male, Jim recalls being treated “gingerly” and “carried very tenderly almost” whilst officers were aggressive towards Black members of the group. The protestors were then arrested by the city police and taken to a precinct jail.

The police then went around with photographs trying to identify the eleven protestors in the Capitol. Jim said: “The District of Columbia is a southern town operating in southern ways. They had a nice little system where you round up everybody and arrest them and sort them out later.”

That evening, President Johnson delivered a televised address to the nation where he introduced the landmark Voting Rights Act. This was a monumental day in civil rights history as the legislation outlawed discriminatory practices which had kept African Americans disenfranchised for generations.

At the end of his speech, Johnson signalled his solidarity with the moment, uttering the famous civil rights refrain, “We Shall Overcome”.

“I did not hear the speech”, Jim recalls, “because I was in D.C. jail.” To Jim and the protestors, their incarceration was deeply symbolic. “We regarded that so cynically and with such co-option”, Jim admits, and it consolidated the deep mistrust that activists felt towards President Johnson.

Though the 36th president is remembered for implementing landmark civil rights legislation, Jim believes it was only achieved “on his terms.”

A month later, Jim and the other protestors were convicted and sent to a D.C. Department of Corrections jail, an all-male, adult-only facility which housed some of the city's most violent offenders.

When Jim arrived in the jail’s canteen, it soon became apparent what his and others' involvement in the movement meant to the majority-Black prison population.

“They treated us like royalty”, Jim remembered, “they didn’t even let us into the food line!” To their astonishment, some of D.C.’s most hardened inmates thanked them for their courage and dedication to the cause. Together, they all broke into a chorus of the famous civil rights anthem, “We Shall Overcome”.

This was not Jim’s first involvement in the Civil Rights Movement. The year prior, aged 19, he volunteered as one of 1,000 white students registering Black Americans to vote as part of the Mississippi Freedom Summer.

With a mere 7% of African Americans registered to vote in the state, the principal objective of the summer was to enfranchise Black Mississippians, and bring issues of poverty and racial injustice before a national audience.

In June 1964, Jim arrived in Holly Springs, Mississippi and knocked on doors in Mississippi’s Black community for the next eight weeks. But within one of the South's most unrepentantly racist states, he faced great resistance.

“The whole notion of fear in the state was atmosphere”, Jim recalls, “it was a climate. It was like the weather.” Danger-to-life was a reality for all participants of Freedom Summer.

As Jim arrived in Mississippi, an FBI investigation was underway into the disappearance of three fellow volunteers: James Chaney, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman, who were kidnapped and murdered by the Ku Klux Klan.

One day, Jim was followed by three white men after being spotted with a local Black, high school student. “Boy, you better be out of town by sunset if you don’t want to end up like those three”, they threatened. “How the ghosts of those three shadow all our work”, Jim later wrote in his journal.

But fear only strengthened the commitment of the freedom volunteers and for Jim, this was never more apparent than when volunteers and locals joined together to sing ‘We Shall Overcome’, in Mississippi’s Black churches.

“There was an urgency to the way that was sung”, Jim recalled, “with an edge beyond the music and the words.”

Jim believes Freedom Summer changed his life.

The experience taught him how to be an effective white ally within the Black freedom movement. He said: “The most valuable thing we learned was to shut up, step back and try not to be a leader."

Bob Moses, activist and architect of the summer program, significantly influenced Jim’s philosophy and practices in his life. “He taught me to never take power in our own hands. You’re most powerful when turning it over", he remembered.

For over half a century, Jim has been striving towards the same goal of racial equality with an unrelenting energy and enthusiasm. His career as a public-school teacher and trainer for interpersonal and political movements attests to a lifetime of service, informed by the teachings of Freedom Summer.

At 76, he is committed to educating the next generation and teaches civil rights history in schools. “I’m not teaching you history,” he tells his students, “I’m recruiting.”

When asked whether the summer made a difference, Jim laughs. “I said back then, ask me in twenty years!” he said. Sure enough, the answer came over thirty years later when Jim received an email from Larry Taylor, a Black Mississippian who he’d spoken to on his porch in 1964.

The email read: “We were very cautious of you because you were white, and could not understand why someone like you would care whether we lived or died.

"But after that talk, for the first time in my life, I felt like I was somebody. You made me love myself, and that was the best thing you could have done not only for me, but for any human being.”

Reflecting on the letter, Jim said: “It testified my whole life, and I’ve never been able to read it aloud without crying.”