Resilience

Understanding the journey from trauma to crime.

The UK has the highest prison population size as a proportion in the EU, and one of the highest rates of reoffending in Western Europe. Political efforts in the Netherlands and Scandinavia to better understand criminality have shown to effectively reduce these numbers in their countries.

In May 2020, a report from HM's Inspectorate of Probation in the UK analysed the role that trauma plays in crime. The report welcomed an "improved understanding on the psychological, health, social and behavioural impact of trauma upon individuals as well as broader cultural, socio-economic, and socio-political populations" on a widespread level. However, it was found that in the UK "we do not always acknowledge this in sentence planning, risk management or use it effectively in rehabilitation or reintegration."

The Benham siblings are no strangers to the effects of trauma and how it intertwines with crime. This is their story.

In 1994, a lone 12-year-old girl walked into a police station in a small town in the midlands, UK. She had bruises and marks on her body and handprints up the backs of her legs. She told the officer that she didn't want to go back home. She was taken into a room for questioning, where she voluntarily entered the care system.

Ashley Benham had been known to the county's social services' child abuse department since she was one month old. Her file's earliest entries describe her as frequently 'very dirty'; arriving to nursery 'unwashed, in a dirty nappy'; to hospital 'very badly dressed' and cold in bad weather; and as being 'left in [her] cot for long periods'.

At 14 months she was refused medication by a parent for two days until she suffered a convulsion. At 17 months she had a 'burn mark on [her] arm,' with 'no satisfactory explanation'. Soon after, Ashley caught a bowel infection and doctors deduced that she had not been given the correct dosage of medicine at home.

The authorities finally intervened, and Ashley was taken into care for two years. However, she was returned to her mother and new stepfather in August of 1986, where she alleges the abuse continued for another eight years.

Once Ashley ran away she was placed in a foster home where she stayed throughout her teens. She worked hard, studying to be a social worker at the local college when she was 17. She was always a bright student (described jovially as 'brainy' and a 'teacher's pet' by social workers) and passed with a top grade.

Ashley went on to work in sales and insurance, and then in finance, where she earned high commissions. Now, at 37, she runs a successful business. Her and her partner currently foster one young girl, and have fostered ten children altogether over eight years.

Ashley cuts the picture of somebody who has emotionally outgrown her past, and is now able to maintain a healthy and loving life. She speaks matter-of-factly about the abuse and abusers of her past. "I suppressed a lot of it," she says, "and used it as a tool to gain independence. I was a high achiever so I didn’t have to suffer again, and could be self-reliant."

Ashley's two-year older brother, Daniel, had a similar start. After their stint in care, when social services returned the siblings to their mother and stepfather in 1986, Daniel was six years old.

Ashley says at this point her brother's abuse consisted of being locked naked in a cupboard for long periods, having his toys smashed up so regularly that he took to hiding them in bushes along the street, and having his head forcefully held underwater whilst loud music was played, to cover the sound of his suffocating.

Child authorities noted that Daniel was seen to threaten other children with weapons from the age of seven. One day, two years later, the siblings' stepfather beat their mother, knocking out teeth and causing her to nearly lose an eye; both Ashley and her mother recollect that nine-year-old Daniel had been tied up naked in two feet of snow.

When the authorities arrived, Ashley says their mother instructed them to take Daniel away, and in doing so protected their stepfather. "She chose him over Daniel," she says today, still sounding in disbelief.

Despite an entry in Ashley's own social services' file saying that Daniel was 'very protective of her' and that 'it is felt that these two should not be separated', Daniel was taken away soon after the incident. Ashley would only see him a handful of times over the next decade.

At his new foster home, ten-year-old Daniel was so scared he slept with a knife under his pillow, Ashley says. "Daniel's respect and trust for his parents died," she says. "He entered survival mode".

Daniel was given up after two years, and then began a long and tumultuous period shunting between various school and foster placements, all of which broke down, according to later documents. He was expelled from school, eventually teaching himself to read and write. "I was totally on my own," Daniel says of this time. "No family to rely on."

"I was full of bravado and angry and was always in trouble," he added. "I was still coming to terms as my life caught up with me. I was getting in with the wrong crowds, easily influenced."

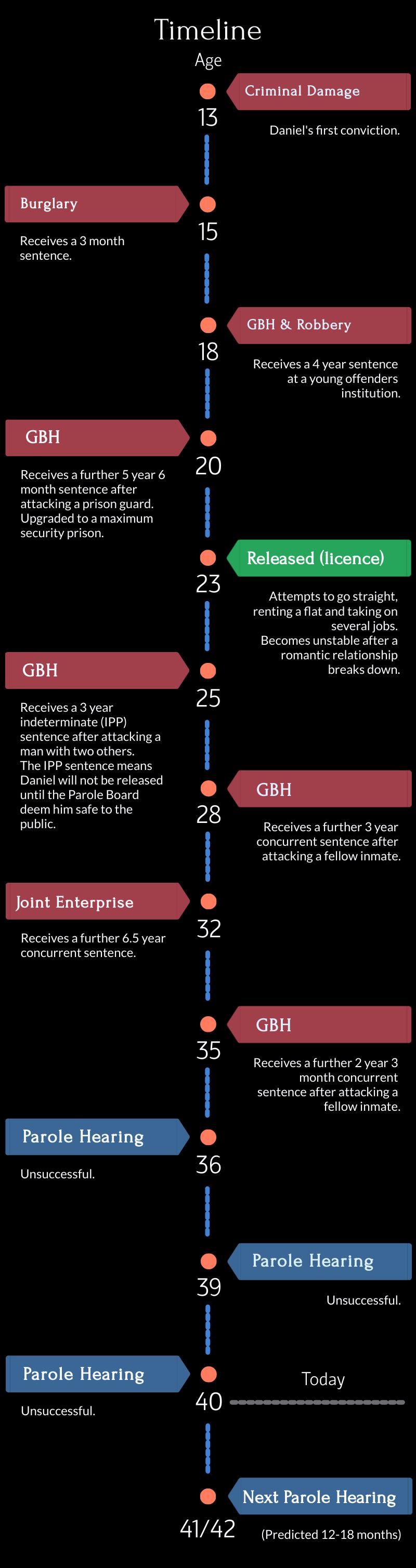

From there, the descent into criminality began.

A Daily Battle

“I’m gonna die in prison, I’m never getting out. I’m not coming. I’m gonna die in prison. You don’t understand. I am cursed."

This is 40-year-old Daniel on a bad day, hurriedly talking to Ashley on the phone. They talk every day, and Ashley frequently coaxes her brother out of such negative states of mind. It's made them become incredibly close, and she understands him.

The stakes can be high. "It is not uncommon for him to call and say to me, 'I just want to die'," Ashley says. "The irony is that his instability, which has been caused by the sentence and the environment he is in, is now used as a reason for him not being released.

"He's all I've got in the world. I see him fading away day by day, unable to cope. I dread the day I get the call that tells me he couldn’t cope any longer.

"He pushes people away as well, but I’m used to it, I understand the psychology behind it. It’s easier for him to get rid of people because it hurts."

On better days, like his birthday, Daniel will talk about his love for music, art, animals and clothes, with Ashley and their grandmother, whose phone is put on loudspeaker next to Ashley's to create a three-way conversation. Recently, Daniel has begun to talk about his trauma.

"The horrible memories have laid dormant for so long," Ashley says. "My brother has only just started to talk about it. He is facing his anger issues. He used to be angry as a way of coping. He has been learning to cry."

Parole

Although Daniel is over-tariff and has served his time, the terms of his IPP sentence mean that the Parole Board will only release him when they are convinced that he won't reoffend. He has had two unsuccessful hearings since 2018, the Board citing his lack of cooperation with authority figures as a key issue.

Each unsuccessful parole hearing is a painful setback. "It’s hard to be strong, not knowing when I’m going to come home," Daniel says. "I’m around what feels like a war zone. So much darkness and depression, it feels like a bad dream and it’s never ending.

"I was very young when I got the [IPP] sentence. I was angry and unwilling to work with parole. I was finding my feet and still surviving, finding out who I was."

The Board are aware that Ashley and her husband are offering accommodation and employment for Daniel upon his release, and do support this. "I just want to come home and be with my family, put down roots," Daniel says. "This is when I will heal, but these wounds will take time".

Daniel must wait another 12 to 18 months for his next hearing. At that point he would have spent close to three decades in and out of the criminal justice system, with a current, single stretch of 17 years.

Trauma-Informed

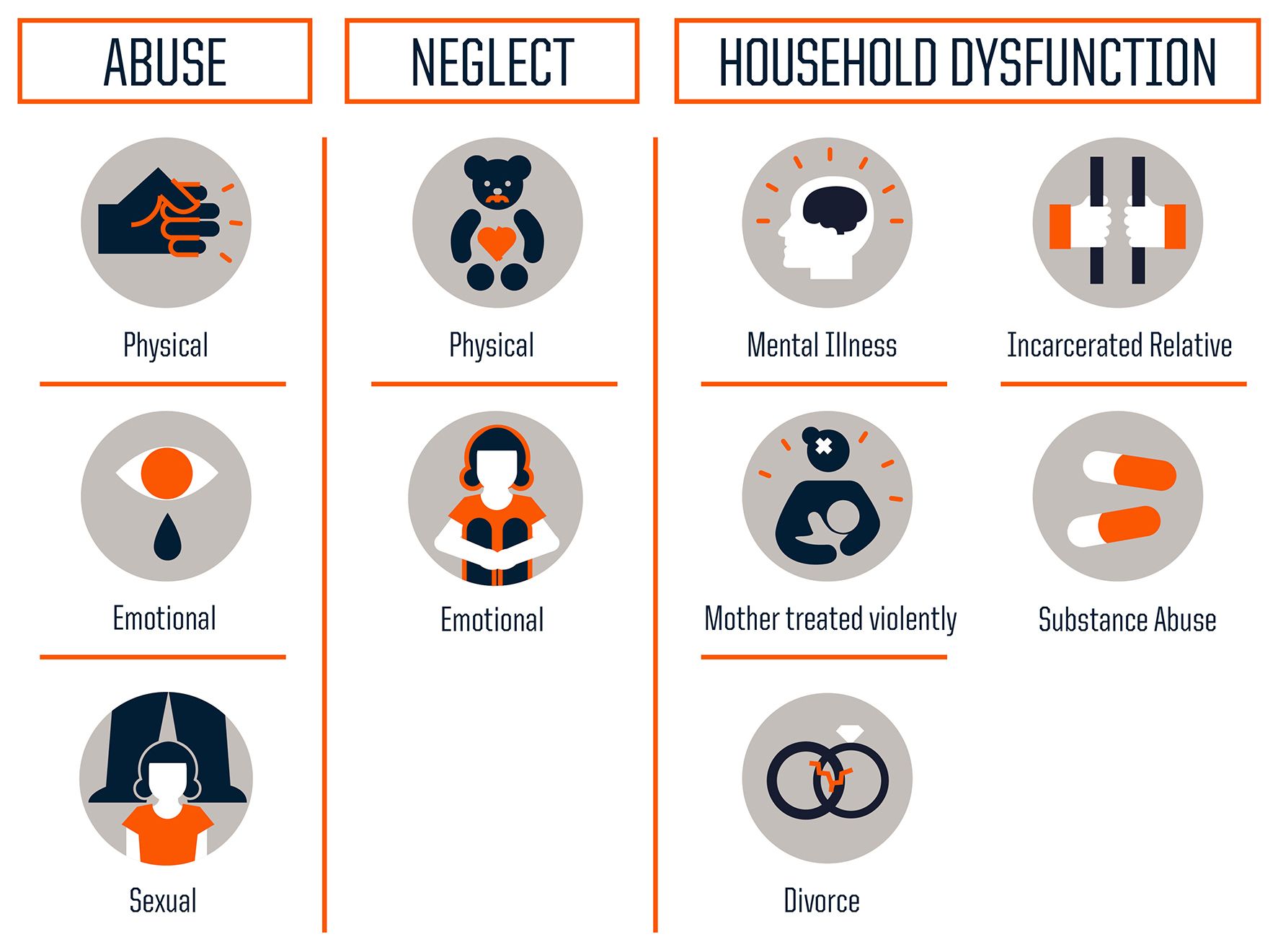

Ashley and Daniel's abuse can be quantified using an ACE score. ACEs are adverse childhood experiences that can impact a person’s behaviour, health, and psychology across their lifetime. One ACE equates to one negative childhood experience, from any form of abuse or neglect to living with a parent with a mental health illness. By the time of his first arrest, aged 13, Daniel would undoubtedly have already acquired a high ACE count.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention / Credit: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention / Credit: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

ACEs play a significant role in criminality. A 2018 study in Wales found that whilst 46% of the national population had experienced one ACE growing up, 84% of the prison population had. Similarly, 12% of the national population had experience four or more ACEs - compared with 46% of the prison population. Other studies attest to the significant role ACEs play in criminality and reoffending, and recommend early treatment intervention programs to stop criminal careers developing.

Whilst this goes some way in explaining Daniel's actions, why didn't Ashley also lead a life of crime? Harvard University's Center on the Developing Child (CDC), who produce leading research on ACEs, identify one main factor: resilience. And they say that resilience - 'the ability to overcome serious hardship' - is not found in all children.

So why did Ashley develop resilience? The CDC found the single most common factor for children who develop resilience is 'at least one stable and committed relationship with a supportive parent, caregiver, or other adult'. A key difference between the siblings was that Ashley eventually found consistent nurturing, staying in one foster home from age 12 to 18, whereas Daniel's teenage years were more unstable and spent in a variety of homes and institutions. (The role of the care system is significant - MOJ's Surveying Prisoner Crime Reduction research from 2012 found that whilst only 1.5% of the total population of England and Wales are in the care system today, they will go on to represent roughly a quarter of our total prison population.)

The CDC also states that children with resilience also 'typically have a biological resistance to adversity'. Ashley says that she suppressed and internalised her trauma, leading her to refrain from violence. In Daniel's case however, as his psychotherapist's evaluation claims, he expresses sadness using anger, at times when others may cry or be vulnerable. Unfortunately, using a coping mechanism such as Daniel's will greatly increase a young person's chances of falling into crime, setting off a chain reaction of escalating violence and incarceration if left unabated.

According to the CDC's research, it is these divergences - Ashley's stable foster placement, and in-built 'resilience' and internalisation of her trauma - that most likely impacted the course of the Benham siblings' lives.

Academics and professionals continue to research and discuss trauma and criminality today. Research this year from medical journal The BMJ into trauma and violent offending amongst adolescents outlined the 'need for early identification and treatment of trauma-related symptoms, not only in order to decrease the human suffering caused by it, but also to prevent criminal behaviour and other adverse social outcomes in later life'.

Victoria Greening, lawyer and founder of firm Resolution Chambers, asks what the legal profession can do better. In August, Greening wrote in Bermuda's Royal Gazette: "Criminal justice social work reports use terms such as “background”, describing childhood adversity as a “poor upbringing”, without actually referring to ACEs or giving a real sense of the misery, despair, trauma and toxic stress experienced by offenders when they were children. These reports almost always fail to connect the impact on the adult defendants that these ACEs truly have had."

Greening continues: "If lawyers are going to get anywhere with this model, other professionals that make up the justice system — prosecutors, judges, prison officers, police — need to play their part by becoming trauma-informed."

Better understanding trauma better does not have to equate with being 'soft on crime', a fear that often restricts rehabilitative progress in the UK's criminal justice system. HM's Inspectorate of Probation concluded in its May report into trauma-informed practice: "Being trauma-informed is not being overly sympathetic to the person who has committed an offence and does not take away from the victim’s experiences. Instead, [it] supports reintegration by helping a person to have a better understanding of why they committed their offences, enabling them to change their behaviour."

This week, Daniel has been given access to purple visits, which allows him video calls with his grandparents. Ashley is also providing him with new clothes, and he is in high spirits, though his mood can change quickly and depressive episodes are common.

Regardless, Ashley will continue to support her brother until he is released, and they can be reunited under one roof for the first time since they were children. Only this time, free from abuse. And, hopefully, free from crime for good.

All images from PixaBay.

Names have been changed in this piece to protect victims' identities.