Silence is golden: A rule unfollowed by former Kyiv Post journalists

“Without independent journalism, you cannot get democracy”

On November 8, the Kyiv Post was closed for what its owner, Odessa-based property tycoon Adnan Kivan, called “restructuring.”

The paper remained shut for exactly one month before announcing on social media that it would start delivering news again on December 8. However, this news is produced by a completely new team of reporters operating under an entirely new editorial leadership.

The Kyiv Post, which printed its first edition in October 1995, earned its title as Ukraine’s most trusted English media outlet. It broadly managed to sustain its independence, surviving even the reign of Viktor Yanukovych, known for his oppressive approach to the media.

Kivan obtained the paper from Mohammad Zahoor in 2018. In March that year, the new owner featured on the Post’s front page as saying: “Without independent journalism you cannot get democracy.”

Last month, however, in an apparent attack on press freedom, Kivan closed the paper and cut off journalists’ access to the website, and later their emails and the Slack messaging platform.

Kivan later offered reporters to return under new management. According to Max Hunder, a former Kyiv Post journalist, the Post would also be taken in a new direction, focusing on softer and more promotional journalism.

Max Hunder and Asami Terajima were among the 30 former Kyiv Post journalists who opted to walk away from the publication and start their own media outlet, as they no longer deemed the Kyiv Post to be independent.

Below are conversations with them about what happened over the past month.

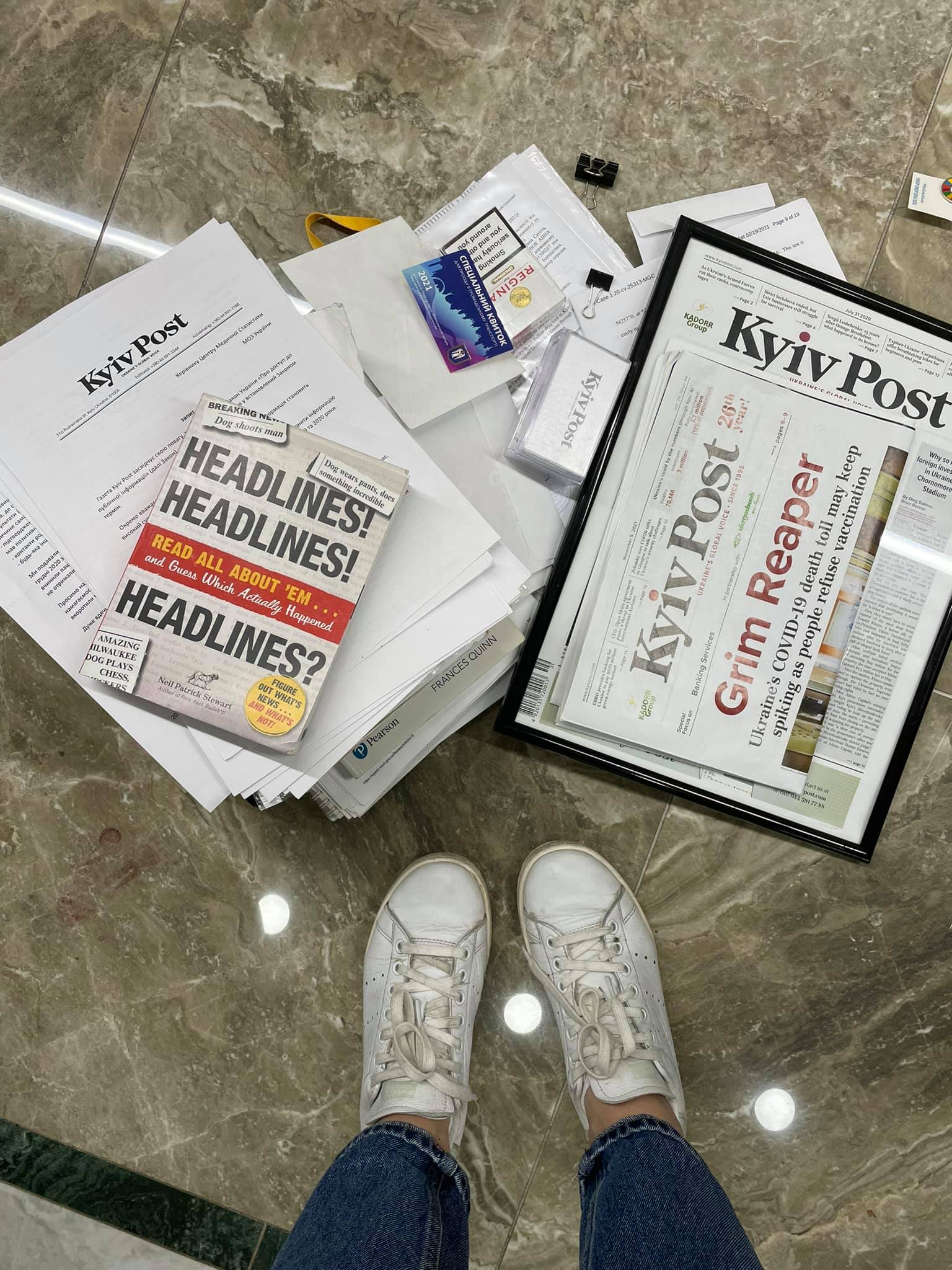

Image credit: Anna Myroniuk

Max Hunder

Hunder, who has British citizenship, was forced to return to London within seven days after leaving the Kyiv Post, as his former employer reportedly contacted Ukrainian authorities to revoke his visa.

“It’s actually pretty horrible having your visa taken away, and it’s fairly unpleasant having to be displaced. From what I understand from a top immigration lawyer, my employer was not bound by law to tell migration services that the employment had been terminated, but they chose to.”

The main image displayed shows the Kyiv Post's former chief editor, Brian Bonner, announcing that the newspaper is being shut down on November 8.

Max explained what happened on that day from his perspective as a business reporter at the newspaper, sitting in a quaint Richmond café on a chilly November afternoon.

Image: Kyiv Post office in Kyiv, general meeting, chief editor Brian Bonner announces that the newspaper is shut down. Nov. 8. Copyright- Pavlo Podufalov

After the failed negotiations over the phone, in which the reporters asked Kivan to sell them the paper or the trademark, Max explained how the owner attempted a compromise.

“Kivan offered us our old jobs back, but by that point, our trust in him was completely shattered and we had found out that the new CEO, Luc Chénier, was going to take the paper in a different direction.

“He was going to focus the paper on soft, promotional journalism. I just thought, are you seriously going to focus on tourism and food when there are a hundred thousand Russians on the doorstep?

"To turn it into something writing about nice restaurants and football, that’s a ludicrous decision.

“I think it will be pretty hard for the new [relaunched] Kyiv Post to be taken particularly seriously by anyone who engages with the media in a serious way.”

“Silence is golden”

“When Kivan bought the paper in 2018, he told the newsroom that ‘silence is golden’”, Max said.

“This was a really awful thing for a proprietor to say to a newsroom. People were put on edge and then he was never to be seen again until September 2021, I believe.”

When Kivan returned to the Kyiv Post newsroom in September 2021, it was just after the paper had published a critical article about Ukraine’s prosecutor general, Iryna Venediktova.

Max recalled: “He said very loudly and theatrically to the newsroom something like: “When you write about the prosecutor’s office, I take shots to the back.”

“He fired us and destroyed the paper, but there are villains above him here, there are people who forced his hand.

“We can only speculate about that [what happened behind the scenes and led to the Kyiv Post’s closure] because he will never say anything in public and we weren’t in the room for those discussions, but certainly the prosecutor’s office is a good place to start," Max said.

Image credit: Anna Myroniuk

Made with Visme Infographic Maker

"The eye of the storm"

A team of 30 former journalists and staff members from the Kyiv Post worked quickly on their new publication, in an effort to retain a reliable English-language source of information in Ukraine.

The image displayed shows the journalists meeting at a co-working space in Kyiv, December 6.

They officially launched the Kyiv Independent online on November 22, receiving support from notable local and international experts on Ukrainian society, including Max Seddon, Olga Tokariuk and Simon Ostrovsky.

Heartening media news, for once: the former staff of the Kyiv Post, which was the only good source for English-language Ukraine news before the owner fired them all, are relaunching as a new website. Eager to see how they get on https://t.co/mxRyT4yah3

— max seddon (@maxseddon) November 22, 2021

Looking back over those first critical weeks, Hunder said: “So much happened that I think I still haven’t processed it fully, it was such a whirlwind.

"I sort of managed to ignore most of the noise because there was so much happening that if I listened to the noise, I wouldn’t have been able to hear anything with this whirlwind of information and discussion going around us.

"It was like being in the eye of the storm.

“Now it is slightly depressing because I had to leave Kyiv when I had really settled in there, but it was important that we got something new going straight away so that people didn’t lose hope and fall into depression or bitterness and resentment.

“It really fired us up, I have never been in a collective of people so fired up as the sacked journalists of the Kyiv Post on the few days after 8 November. I have never seen energy like that.”

Though Max looks forward to the future of the Kyiv Independent, he acknowledged that it has a way to go before operating as a fully-fledged entity that is able to issue more than a volunteer visa.

“There is definitely a sense of sheer excitement at building something new but at the same time people don’t have their salaries anymore, and a few people like myself had to leave the country because their visas were taken away.

“We are overcoming barriers and obstacles to try and create something which we hope will be wonderful.”

For now, the Kyiv Independent is funding itself through subscriptions and donations. It currently has more than 750 patrons who pay a monthly fee. On their GoFundMe page, set up to cover the costs of setting up the new publication, the team has raised over £11,000, surpassing the £10,000 goal.

Max was touched by the support, both financial and verbal: “I wasn’t expecting that, it really overwhelmed me. It has been just so wonderful and emotional.”

Image: The Kyiv Independent meeting at the Beeworking co-working space in Kyiv, Dec. 6. Copyright- Volodymyr Petrov

Asami Terajima

Asami Terajima joined the business staff of the Kyiv Post in April 2021. She travelled to Japan in mid-October to renew her visa, but on November 8, the new visa became invalid. Like Hunder, she is currently unable to return to Ukraine.

As she was in Osaka when the Kyiv Post shut down, she received the news alone.

"Without the team, I would not be where I am today"

Asami felt alone in Japan, thousands of miles away from her colleagues. Seeing them on Zoom, however, and knowing that she will be reunited with them soon, has made her determined to make the Kyiv Independent a success.

“I really think that we have such unique quality, our team of journalists is so united and we have such a positive work environment.

“Every time I see the team on Zoom and their faces it just makes me feel happy, when I see them in person it will bring a whole different mood.

“We all understand the financial risks in this, but we are still moving forward and I think that without the team, I would not be where I am today. I would still be upset and depressed.

"But because everyone is moving forward, I feel the support, and I know I can count on my colleagues. That motivates me to work harder on the Kyiv Independent, so we can become a bigger media outlet and expand our audience.”

Like Max, the sheer pace of events from 8 November has kept Terajima on her toes and prevented her from falling too deeply into sadness for a paper that she has been surrounded by her whole life.

Image: The Kyiv Independent meeting at the Beeworking co-working space in Kyiv, Dec. 6. Copyright- Oleg Petrasiuk

"We need to help Ukraine tell Ukraine’s side of the story"

The image displayed depicts the chaos and violence of Ukraine's Euromaidan protests in February 2014, which ultimately brought Victor Yanukovych's presidency to an end.

The 2014 civil unrest in Ukraine's capital erupted after Yanukovych opted out of an association agreement with the EU, choosing instead to maintain ties with Putin's Russia.

Max, Asami and many journalists reporting in Ukraine, regard the Yanukovych era as one of the darkest times for press freedom in post-Soviet Ukraine.

Asami finished our interview with determined optimism for the future of the Kyiv Independent: “We are going to be fully independent, no matter the backlash and no matter the criticism we get from authorities or businesspeople.

“Independence is the most important quality in journalism and that we believe in. This is something we are not going to give up, and we are going to fight until the end for an independent press in Ukraine.”

Image credit: Christian Triebert, Flickr

Title page image credit: Anna Myroniuk