STAYING AFLOAT:

Could canals hold the key to the UK's housing crisis?

With a chronic shortage of affordable homes, skyrocketing rents, and house building that consistently fails to keep up with population growth, the UK finds itself within the clutches of a housing crisis.

As more than one million households wait for access to social housing, research commissioned by the National Housing Federation reveals that around 340,000 new homes need to be supplied each year until 2026, just to meet demand.

Such scarcity has contributed to a dramatic increase in housing costs, with the median monthly rent in England between April 2021 and March 2022 rising to £795, higher than at any other point in history, according to the Office for National Statistics.

However, for many of the 4.4 million households in the private rented sector, costs are much higher, with median rents hitting a staggering £1,450 a month in the capital – nearly £500 higher than any other region – such expenditure is becoming increasingly unsustainable.

With data published by Shelter revealing that three in five adults aged under 45 have have had to put their lives on hold due to housing problems, it's no wonder campaigners are calling for serious investment in house building.

According to research by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, a third of the 11.6 million households earning £25,000 or less are in arrears on their rent or mortgage, and with average house prices having increased by 9.8% in the last year alone, families have been forced to take drastic measures to avoid soaring prices.

Photo by William Hook on Unsplash

Spanning more than 2,000 miles, the UK’s canal network has proven an increasingly popular choice for households struggling to find affordable housing, with thousands of families opting for a life afloat amid a deepening cost-of-living crisis.

With the majority of the network built at the height of the Industrial Revolution, canals and rivers played a major role in the history of England and Wales, enabling Britain to become the first industrial power in the world.

National Boating Manager for the Canal and River Trust (CRT), Matthew Symonds, said: “We’ve seen a 10% increase in the number of boats on the canals in the last 10 years, with about two-thirds driven by continuous cruising in areas such as London and the south east of England.

“This probably reflects that there’s an issue around availability and affordability of other accommodation and there’s an appeal about being on the water and close to nature. But the cost is certainly an element when you look at the locations where we’ve seen the biggest growth.”

Symonds, who oversees policy and application processes involving the licensing of craft, added: “A lot of boaters tell us that they choose to live on a boat because of the lifestyle and the quality of life, which can be very different to bricks and mortar.

“Canals also have an amazing heritage, you've got the environmental side of it which is calming, good for your well being and your mental health. We saw that during the pandemic, when people began to discover that canals run through all our major cities.”

Photo by Samuel Regan-Asante on Unsplash

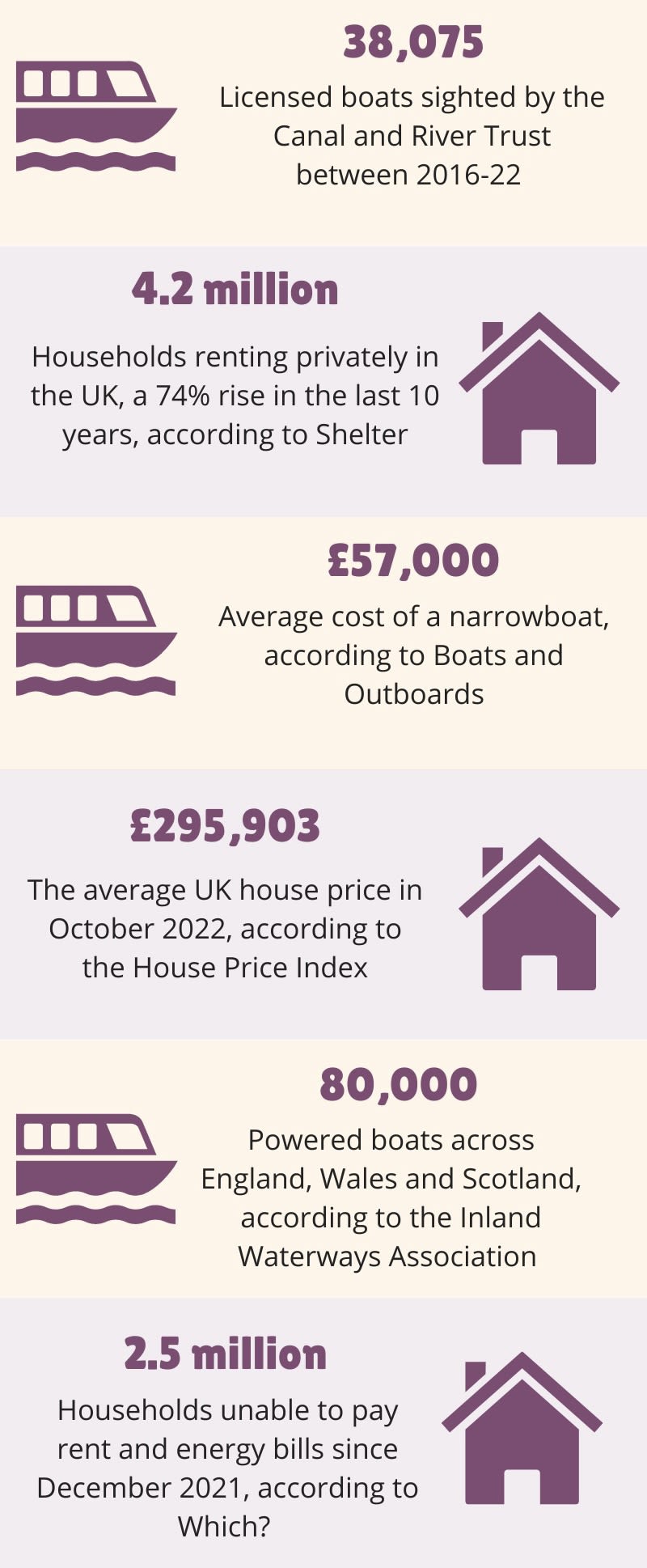

Responses to Freedom of Information requests submitted to the CRT, the organisation caring for the UK’s 200-year-old waterways, reveal 38,075 licensed boats have been sighted since 2014.

The Trust put the total number of “liveaboards” at around 25%, an increase of 15% compared to 2011, while the Inland Waterways Association has said there are around 80,000 powered boats across England, Scotland and Wales.

Although the reasons why families take to the water vary, there is no doubt that affordability is a significant factor, with a London Assembly report calling for extra mornings to tackle overcrowding amid a surge in house prices.

Citing the appeal of the capital’s more than 100 miles of canal, the report stated that while more and more people are finding life on a boat a more affordable option, the number of moorings and facilities has failed to increase in line with demand.

And it seems more and more households are seizing on the financially attractive opportunity, with more boats on the canal now than during the height of the Industrial Revolution in the 18th Century.

According to leading marine finance lender, Promarine Finance, finance deals for boats increased by nearly 40% in 2021 alone, with a particular surge in demand for finance for live-aboard vessels.

“We’ve noticed a surge in demand for boat finance, with a rapid increase in young people moving to live on the canals on narrowboats and wide-beam boats,” said Stuart Austin, Director of Promarine Finance.

“Live-aboards such as canal boats are no longer considered an option for just the retiree, and instead are drawing in people who are seeking alternative lifestyles with freedom from the traditional housing options.

“Younger buyers want to get on the property ladder and boat ownership is a practical and affordable alternative to renting, with the ‘race for space’ fuelling the housing crisis, pushing buyers to consider more cost-effective living arrangements."

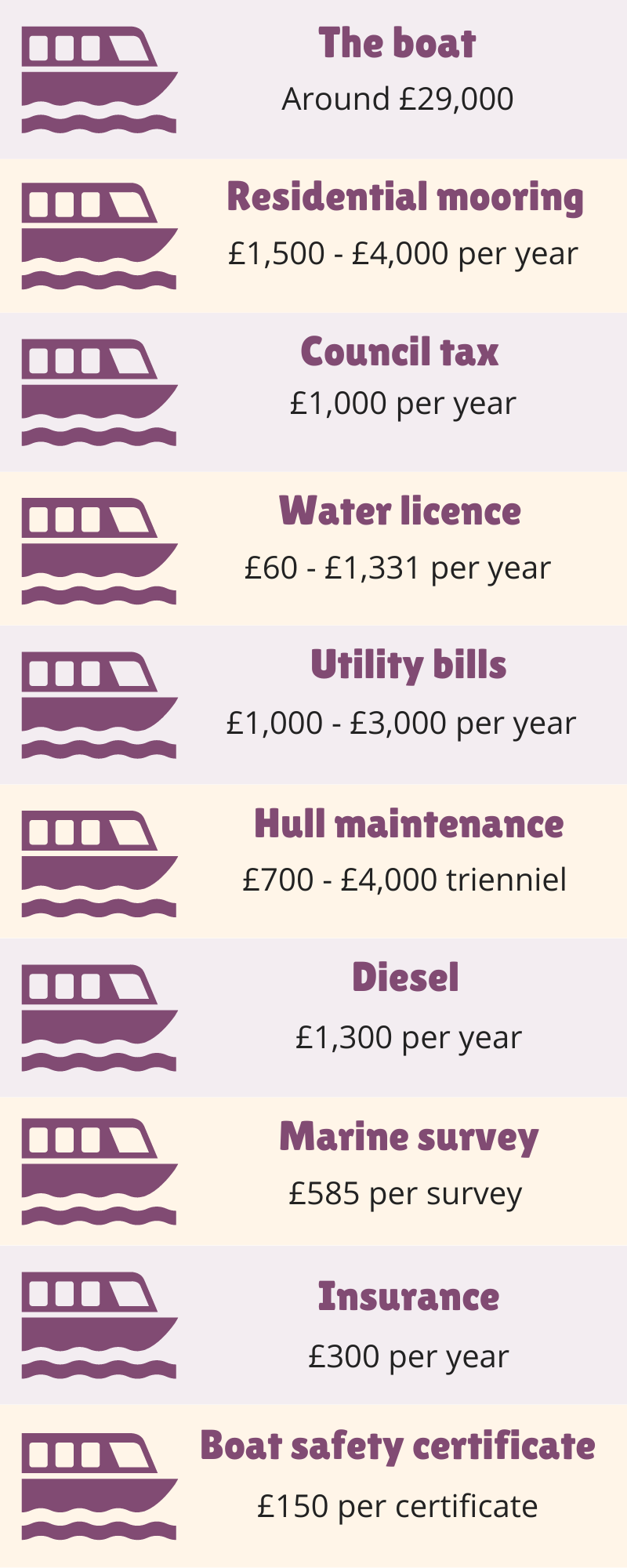

He added: “The running costs of a canal boat are significantly cheaper than that of a property whether that is rented or owned, especially with the recent spike in energy bills, so canal boats are a solution to those struggling to find affordable housing.

“On a canal boat, there are ways to be completely self-sufficient, for example, solar panels with a battery storage can provide you enough power to run the electrics on the boat during the summer months.

"It is cheaper to buy a boat, as it includes fewer bills to pay, for example council tax. However, the logistics around continuous cruising must be planned in advance. It is worth noting that quality boats have been and still are in short supply, with prices increasing by at least 20% in recent years."

Photo by Polina Volkova on Unsplash

Tim and Sam inside their 53-foot narrowboat, Mary L. (Picture: Tim and Sam Biglowe)

Tim and Sam inside their 53-foot narrowboat, Mary L. (Picture: Tim and Sam Biglowe)

The couple have been moored in Hayes and Harlington for the last year. (Picture: Tim and Sam Biglowe)

The couple have been moored in Hayes and Harlington for the last year. (Picture: Tim and Sam Biglowe)

“We'd worked very hard for the money that we made, and we wanted to have something to show for it. That's why when faced with the option of living on a boat, it all fell into place” – Tim and Sam Biglowe, London.

When Tim and Sam Biglowe arrived back in the UK after more than three years of teaching in Vietnam, they never expected to call their quaint 53-foot narrowboat home.

Now moored at the Willowtree Marina in Hayes and Harlington, the couple had intended to buy a small house in the north of England, but having saved enough money to afford a sizable deposit, a lack of credit history meant they were unable to apply for a mortgage.

Tim, 31, and Sam, 36, who had never lived together, said they were shocked by the affordability of canal boats. Determined not to spend their money on increasing rent, but desperate to get onto the property ladder, a life on the canal soon became an appealing prospect.

Purchasing their boat, Mary L, in 2020, the couple renovated the vessel into a permanent residence – also known as a 'liveaboard' – and spent the next year cruising the canal network.

Required to change their mooring every two weeks, the decision proved cost-effective, with their lack of a fixed address enabling Tim and Sam to save money on bills such as council tax and rent.

Watch below to find out why Tim and Sam purchased their canal boat.

“The costs will break a lot of people because many of those who live on boats are on very low incomes and are not the kind of people who necessarily have money to spare. Frankly, a lot of people are really going to suffer this winter” – Pamela Smith, 61, Yorkshire

While the prospect of affordability pushed many to consider a life on the canal, the deepening cost-of-living crisis has seen the once significant savings made from moving onto the water dwindle, with some boaters struggling to cover the most basic of costs.

With the cost of coal increasing by almost double, boaters up and down the UK have also been hit with an 8% increase in licence fees, taking the average cost of a boat licence to £823.68 per year, including Pamela Smith, Chair of the National Bargee Travellers Association.

Purchasing her canal boat more than 17 years ago after moving to an area with significantly higher property prices, life on the canal seemed like an obvious choice for Pamela who was looking for a flexible solution to the financial challenges involved with moving home.

But despite her pre-existing passion for boating and the appeal of a more flexible way of life, even Pamela has begun to notice the financial pressures of sustaining life on the water, with increased running costs forcing her to cut down on areas such as heating.

She said: “Prices are going up and up, and it’s gotten to the stage where I no longer run my stove at night, so I wake up on a cold boat in the morning. One of the things I’ve really been avoiding is running my engine to charge the batteries.

“I’ve tried to minimise the distance I travel and the diesel I use when cruising because it’s frightening how much it might cost me to actually fill up my diesel tank. If I wanted to go for a long cruise, I’d ideally need a full tank, but I have no idea how much that would cost now.”

Photo by Markos Tsoukalas on Unsplash

Pamela first purchased her canal boat 17 years ago. (Picture: Pamela Smith)

Pamela first purchased her canal boat 17 years ago. (Picture: Pamela Smith)

Matthew Symonds is the National Boating Manager for the Canal and River Trust. (Picture: Matthew Symonds)

Matthew Symonds is the National Boating Manager for the Canal and River Trust. (Picture: Matthew Symonds)

However, it’s not just increasing energy costs that have made life on the canal increasingly difficult for Pamela, with the CRT's recently strengthened policy on continuous cruising forcing boaters without a home mooring to travel at least 20 miles within their licence period.

“Although there’s no requirement for range or distance, the Trust decided that they would take enforcement action against all boats travelling less than 20 miles. In the stroke of a pen, boaters without a mooring were suddenly told that their annual travel patterns were unlawful.

“Before 2015, people were managing quite adequately to get to work and to get their children to school, but now most of us, especially in remote parts of the waterways, are forced into using vehicles to get to work because we're having to commute such long distances which is just an additional cost."

Pamela added: “When I'm 20 miles away from my place of work, I have to get up a lot earlier to drive further on small country lanes that you can't go fast on. That's really exhausting, and at that point of your annual waterway journey, you don't really have much of a life outside of work.

“And this doesn't include being able to find a mooring. The demand for moorings way outstrips the supply, so finding a suitable mooring is virtually impossible. If you live aboard, most moorings are not residential which means you can’t lawfully live on your boat if you stay there.

"A lot of people have come onto the waterways because their previous way of life was soul-destroying, they have minimal amounts of money coming in and would otherwise be homeless if they didn't live on a boat, so they're going to be a lot worse off."

Pamela estimates the number of residential moorings rests at around 5%, and with demand surging in desirable areas such as London, boaters can expect to pay in excess of £4,000 per year for a spot, higher than total council tax bills for some households.

In 2018 alone, boaters in Brown's permanent mooring in Uxbridge saw mooring fees soar by a staggering 89%, increasing from a yearly figure of just over £9,000 to £12,521 in three years, threatening to push those within the community off the waterways.

And with canal boats far more likely to depreciate in value compared to bricks and mortar, the rate of return on investments can diminish significantly with the costs of maintaining a vessel increasing as time passes.

While a life on the water may offer renters an escape from the clutches of rising rent and energy costs, for Symonds, the canals, which themselves are experiencing overcrowding, are by no means the sole solution to the housing crisis.

He said: “There's lots of costs you need to think about which, when you add up and include the extra work that you have to do living on a boat, it isn't as straightforward as just being cheaper. It's a case that maybe there's different costs, but they're not always financial costs.

"The canals are also limited in their scope and have many uses, so even if we filled them all with more boats, they’d really only make a small dent in the pressure of housing needs, so they don’t solve the housing stock shortage.

“It’s great if people do want to live on the canals, but there has to be a balance because they’ve got to be available for lots of other people to use them as well. There aren't that many miles of canals that run through our towns and cities, so they won't give that number of mooring spaces for boats."

Polly Neate, Chief Executive of Shelter, said: "The dire shortage of affordable social homes means one in three private tenants are shelling out at least half their income on rent. With private renting too pricey for many, it’s no wonder we are seeing people scrambling to find any alternative they can - even a canal boat.

“There are two ways the government should help people to keep a safe and secure roof over their head. Firstly, it must urgently end the freeze on housing benefit and secondly, it must build a new generation of quality social homes with rents pegged to local incomes.”

"Welcome aboard our floating home"

Tired with the stress of juggling rent and other bills while being a single parent, Hannah Bodsworth, 38, in search of an affordable, more simple way of living, made the bold decision to escape life as she knew it and moved onto a narrowboat with her son, George, 8, in 2017.

Now happily embracing an off-grid lifestyle, moving onto the canal was a life-changing choice for Hannah whose outgoings are more than £1,000 less than when she was renting a two-bedroom house.

Working as a freelance photographer, Hannah was just about able to keep up with rent when working full-time, but life was chaotic and trying to balance a career in marketing with a photography business while spending time with her son left her feeling burnt out.

“I was just spinning plates, and couldn’t really see a way out with me continuing to be in a house. I was exhausted and not really seeing much of my son. I had a choice – I could cover the costs, but then I wasn’t going to have much of a quality of life.

“I remember towards the end of 2017 I hit a brick wall, my car engine exploded on the way to a meeting with a client. I managed to carry on with the presentation, but afterwards, I crumbled and as I waited for a tow truck I just thought I have to change this way of living.”

A few weeks later, Hannah, whose brother had moved onto a sailing boat 10 years prior, put a deposit on a narrowboat with her savings and a small personal loan, and spent the next four years renovating the interior with the last of the renovations completed in April.

Watch below to hear how Hannah first envisioned a life on the canal.

Hannah, who has seen a number of boaters forced to live in makeshift craft with no insulation, had briefly looked at social housing as an alternative, but due to poor location and a massive shortage of affordable properties, opted for a life on the water.

“I didn’t care what condition the boat was in, I would happily live on a vessel with no insulation just to get out of the trap I was currently in. I remember at that point I was still so relieved that I was getting out of the situation. Although I found it physically demanding, I was just so grateful."

Continuously cruising for two summers before securing a permanent mooring in London, for Hannah, who soon adjusted to life on the water, it was important to get George’s bedroom ready so that he could get excited about moving in.

“After buying the boat I quickly got George's bedroom ready so that he could be comfortable about moving in. It was important to me that he had his own room, whereas my bedroom is also the living room, dining room and office.

“Since moving onto the boat our life is so much better. I feel like I have to pinch myself each day as I didn't know it was possible to enjoy life this much. I still have the odd few minutes where I think about what it’s like living on land, but I always remember how exhausting it was.”

Asked whether she could ever see herself moving back onto land, Hannah said: “As it stands, I’m happy about the boat situation, and not sure I’m willing to give it up. If George decides he wants to go to a particular school for his GCSEs, we can just up and move.

“It’s not that easy or affordable to move anymore with crippling credit reference fees and it’s just not as convenient to relocate to another part of the country, whereas on a boat it’s quite straightforward."

She added: “I have it in mind that I might need to get a bigger boat. George is likely to be six feet, so I’m going to have to accommodate his height. Really, I’ll go from there and get him through to his early 20s and then see how I feel.”

Beyond the financial and logistical benefits of living on a boat, Hannah said the close-knit canal community is what has made her transition to the canal bearable, with boaters automatically turning to help her.

Below, Hannah shares her memories of the first night spent on her boat.

Hannah purchased her canal boat for £18,500 in a bid to lead a more affordable way of life. (Picture: Hannah Bodsworth)

Hannah purchased her canal boat for £18,500 in a bid to lead a more affordable way of life. (Picture: Hannah Bodsworth)

Photo by Samuel Regan-Asante on Unsplash